Submitted by Berrin Chatzi Chousein

"My Book Is A Provocation To Come Up With The Beginnings Of Solutions" says Reinier de Graaf Of OMA

Netherlands Architecture News - Jul 09, 2018 - 03:13 13676 views

"The book is a provocation, and it is intentionally not propositional because the things that I address are not easy to fix and cannot be fixed by one individual or even by one profession alone," says Reinier de Graaf, Partner at OMA, the world-renowned international architecture practice.

Dutch architect, architectural theorist, urbanist and writer Reinier de Graaf released his book "Four Walls and a Roof: The Complex Nature of a Simple Profession" last year and situated himself at the core of a new discussion about social housing and the entangled economic system of the architecture profession today.

"This is a larger structural problem. I write about the world from the perspective of an architect who tries to build buildings. And if that is what you do, then of course, any kind of propositional element immediately becomes ridiculous. But the book is a wake up call," de Graaf added.

Speaking to World Architecture Community in an exclusive interview at this year's reSITE ACCOMMODATE Conference, held on June 14-15 in Prague, the acclaimed architect shared his incisive thoughts about his newly-released book, the basic problems of today's housing models, the design process he follows in his studio and the deficiencies of the current architectural education system, especially in the US.

Today's housing serves for profit maximization

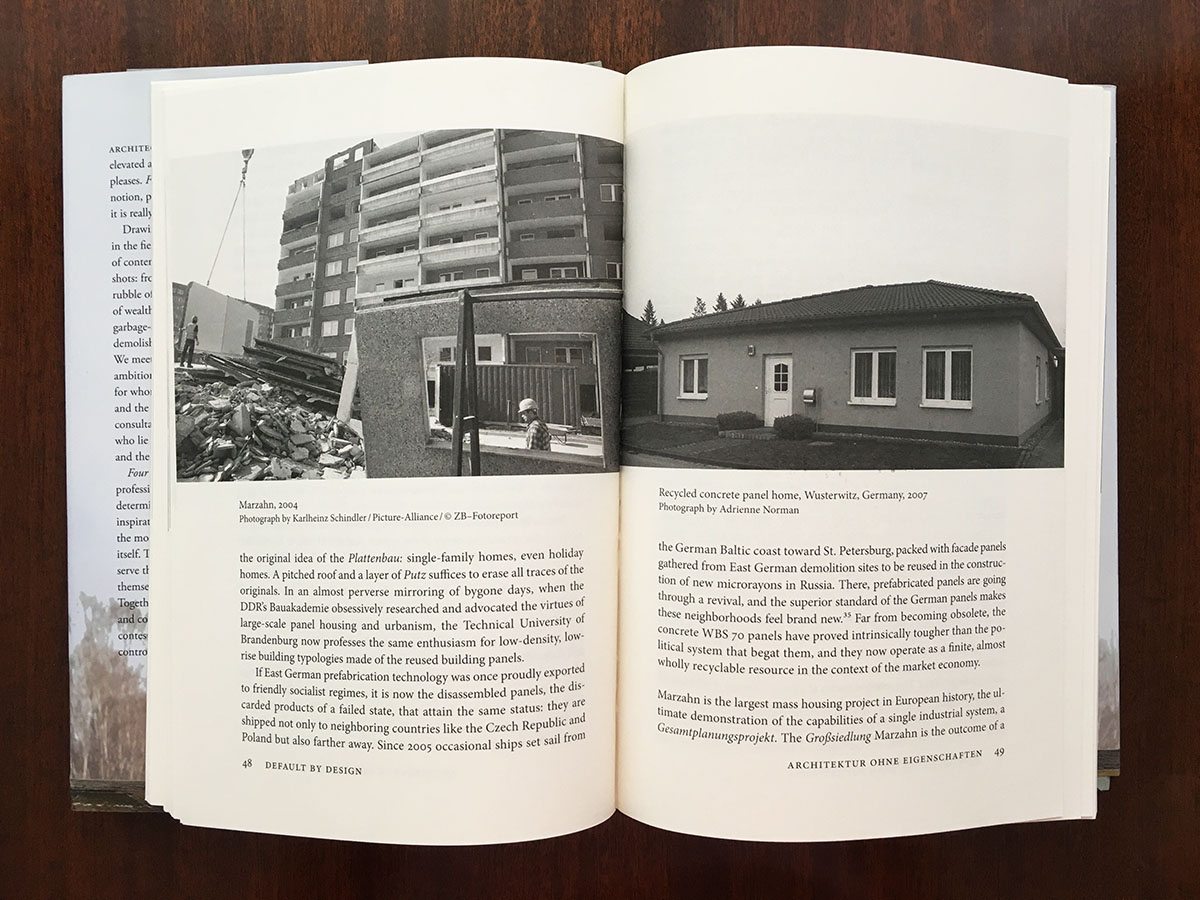

Talking about the massive demolition program of social housing in the 21st Century, de Graaf emphasized that today's housing projects serve mostly as a financial vehicle.

"Social housing either gets demolished or gets listed and sold as luxury housing," said Reinier de Graaf in his keynote lecture at reSITE's 2018 Conference.

"There is a big difference between cost cutting nowadays compared to the era of social housing. Back then, when you designed a cheap building, it meant people could live in an affordable home. Today, when you design efficiently and cheaply, it doesn't mean that buildings are sold cheaply. They're often sold quite expensively."

"Therefore the same set of design instruments serve for a completely different purpose. They used to serve the purpose of providing affordable homes, but today they serve for profit maximization," de Graaf told World Architecture Community.

Holland Green, a new residential complex in London completed in 2016 by OMA in collaboration with Allies & Morrison, to help funding the renovation of the Commonwealth Institute exhibition hall. Image courtesy of OMA; photography © Sebastian van Damme.

De Graaf, 54, joined OMA in 1996 where he leads a wide range of architecture and masterplanning projects in Europe, Russia, and the Middle East. He is also the co-founder of AMO, the think-tank established in 2002 as a counterpart to the architectural practice of OMA.

De Graaf's recently completed projects include the Holland Green in London (2016), the new mixed-use building Timmerhuis in Rotterdam (2015), and the G-Star Raw Headquarters in Amsterdam (2014). De Graaf's FORUM project, a major multi-functional redevelopment in Rotterdam, is under construction in the heart of the city, and is set to be completed by 2019.

Reinier de Graaf and David Gianotten, OMA's Managing Partner, are currently working on a masterplan for the former Bijlmerbajes in Amsterdam, a prison complex in the South-East of the city built in the 1970s. The architects will transform the former 75,000-square-metre prison complex into a new cultural hub in Amsterdam. The project, named Bajes Kwartier, is planned to start this year. Last year De Graaf also revealed the plans for a housing development in Tirana, which will be OMA's first project in Albania.

The modular structure of OMA’s Timmerhuis in Rotterdam, opened in 2015. Image courtesy of OMA; photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

OMA's working strategy

Discussing in detail his own working style at OMA, de Graaf stressed that if an architect is involved in the earlier stages of the design process, he/she can make a difference in shaping design decisions. OMA's think-tank AMO was founded precisely for this reason, according to the architect.

"The earlier you're involved, the more you can make a difference. Indeed, it is easier when working on an urban planning project rather than with a building, where many parametres have already been set. Even more interesting is to be involved before there is a masterplan; this is why we founded AMO, a think-tank in the office to offer services to clients that allow us to be part of the formulation of the questions," de Graaf continued.

American architectural education is deeply f***ed

De Graaf also stated that there is a big gap between academia and architectural practice, and that there is an ignorance of the economic system that buildings are part of. According to the architect, the exorbitant price students pay for architecture education in countries like the US obstruct the learning process.

"For American architectural education system and the only appropriate expression I can find is that it is: deeply f***ed"

"I can speak about the American architectural education system and the only appropriate expression I can find is that it is: deeply f***ed. Students pay enormous amounts of money or have enormous student loans. The financial aspect is so prevalent that students become consumers of education. The huge sums they pay give them an enormous sense of entitlement."

"So, there is no desire to learn. Teachers have to be incredibly careful about what they say. It's the teachers that are being judged on their progress, not the students," de Graaf continued.

"It is a big flaw not only for the architectural education but for architecture in general. It’s like you're working with a 50% handicap: you know the economy of construction but you don’t know the economic system that buildings end up being part of."

OMA transforms Amterdam’s former Bijlmerbajes prison complex into a cultural hub. Image © robota, courtesy of OMA.

De Graaf lectures frequently in the academic and professional realm. He previously taught at Harvard GSD and has recently been appointed Visiting Professor at the University of Cambridge. De Graaf's professorship will focus on how buildings have become an indispensable vehicle for generating financial returns and the implications this has on architectural form and typology.

His program, titled "The Asset Class", "will radically reexamine the history of architecture: not as a succession of styles, but as an ever-involving reflection of the economic system – architecture dictated not by its use value, but by its value as an asset to be traded."

Scroll down to read the interview with Reinier de Graaf:

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: This year, reSITE’s theme is ACCOMMODATE, reffering to the future of housing, affordability, new financial and urban regeneration models. From your point of view, what are the problems or deficiencies with housing today – starting from the design process to the end product? Where does the architect stand in the hyper-financialized economy? Or, if I twist my question: to have affordable housing, should architects resist/change the conditions in a project brief?

Reinier de Graaf: The main problem with housing today is the price, but price is only related to architecture in a very limited way. There's an enormous downward pressure on architects to ensure that the building cost is as little as possible. But there is a big difference between cost cutting nowadays compared to the era of social housing. Back then, when you designed a cheap building, it meant people could live in an affordable home. Today, when you design efficiently and cheaply, it doesn't mean that buildings are sold cheaply. They're often sold quite expensively.

Therefore the same set of design instruments serve for a completely different purpose. They used to serve the purpose of providing affordable homes, but today they serve for profit maximization. In other words, they used to serve the interests of many, now they serve the interests of few.

Architects have very little influence on the economic system but being aware of it already makes a difference. In this respect, most architects are not even close to doing that. It is about the awareness of the context and the awareness of the system that uses it or abuses it. It is time that architects emancipate and the first step to do that is becoming aware of it.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: You have a diverse portfolio at OMA: you design masterplans or individual buildings. If you are to change something in the parameters of a project I imagine it is easier when working on an urban planning project rather than when working on a building, where the program is more or less fixed. So what is your strategy to change something for the public good?

Reinier de Graaf: The first step of an intervention is to decide whether or not you're going to take the job at all – even though architects are often not in a position to be overly picky. But indeed, the earlier you're involved, the more you can make a difference. Even more interesting is to be involved before there is a masterplan; this is why we founded AMO, a think-tank in the office to offer services to clients that allow us to be part of the formulation of the questions. That means the earlier you’re involved, the more influence you have on shaping the questions that you will be asked.

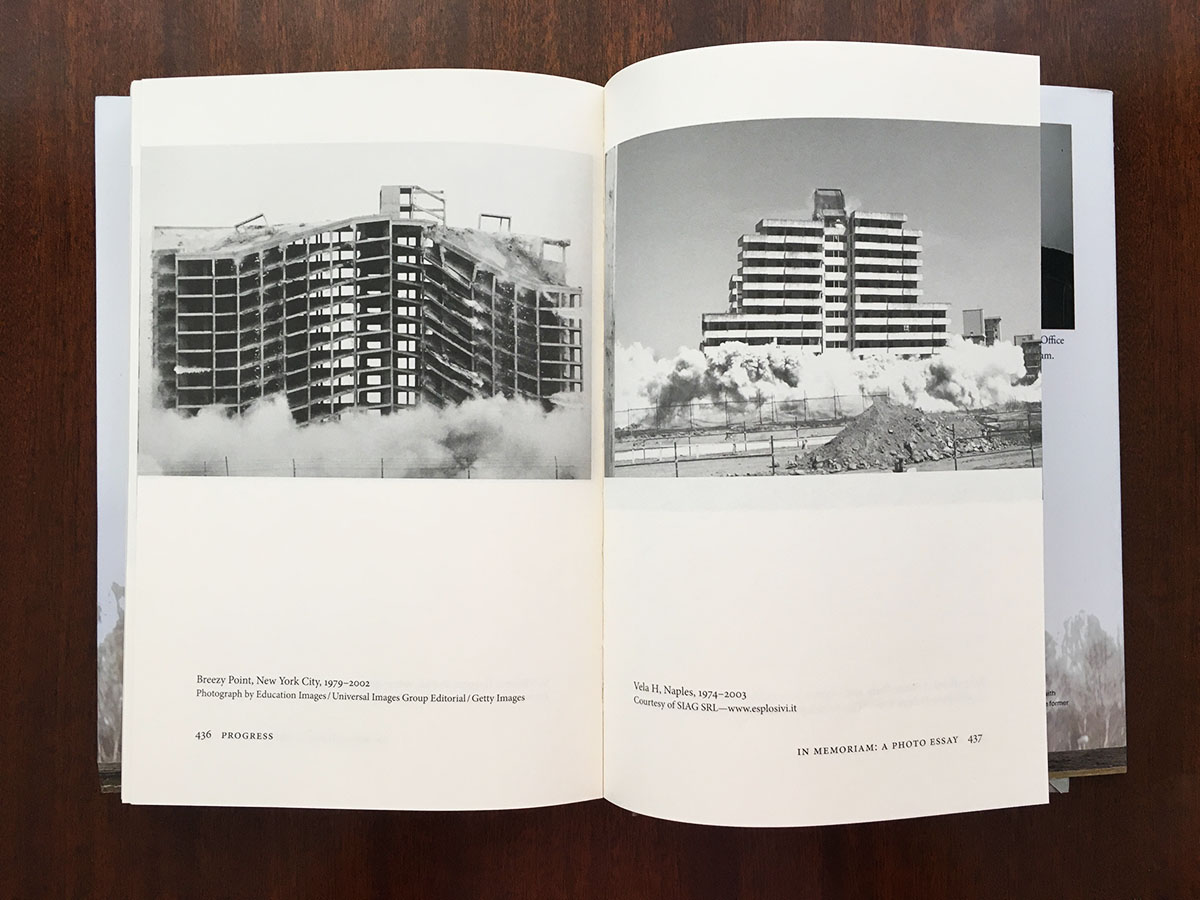

The demolition of social houses documented in de Graaf's book, "Four Walls and a Roof: The Complex Nature of a Simple Profession". Image © WAC

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: You mean, you shape the clients’ vision?

Reinier de Graaf: I’m not sure there is any vision to be shaped. But it brings a sort of awareness, early on, that is pushing what we are going to say.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: You have written a book: "Four Walls and a Roof". I must confess I haven’t read it completely but, as far as I read, it reveals what is really happening in the practice of architecture – discussions with your clients, personal anectodes, analyses and observations – with a cynical language.

Reinier de Graaf: I actually don’t think it is cynical, but people say that. I have a voice and the voice isn't the usual evangelical voice that many people use in this age. I would like to think that I give a sober analysis of the way things are. If I were a cynical I wouldn’t have used over 500 pages to make my point. So the existence of the book is ultimately the proof that I'm not cynical.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: But you don’t have concrete answers or proposals. It’s in the air (maybe it’s just a progress for the next book). Why did you write this book? Was it just to show the complex relationships of the profession? Or, was there a message that you wanted to give indirectly?

Reinier de Graaf: The book is a provocation, and it is intentionally not propositional because the things that I address are not easy to fix and cannot be fixed by one individual or even by one profession alone. It is a larger structural problem. I write about the world from the perspective of an architect who tries to build buildings. And if that is what you do, then of course, any kind of propositional element immediately becomes ridiculous. But the book is a wake up call. And hopefully a wake up call to other people who are a lot more intelligent than me to come up with the beginnings of solutions. So the book is also humble in that sense.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Coming back again to the "housing" issue, I also perused that you document the destruction of the 20th century social housing in your book. In an interview you gave about the Holland Green development you said: "At least one major revolution in architecture is presented each year". Do we need a major revolution for social housing after the destruction of these housing projects?

Reinier de Graaf: The quote was actually about a major revolution that happens in architecture every month. It is actually an ironic statement. I'm questioning the validity of these ‘revolutions’ rather than preaching for another revolution. It is the only chapter in the book that has only images because it's the only instance where images are more powerful than anything you could say about them. The whole volume of demolished housing is so massive that it makes a statement on its own. This is a revolution taking place under our very eyes going in the opposite direction than the social revolution.

I’m not a pessimist but I long for the optimism that underlay that period. It might’ve been called brutalist but there was essentially a very benign ideological program underneath it, whereas now malignant ideologies present themselves in soothing and comfortable aesthetics. Radical politics requires radical aesthetics. I think the revolution we need is to simply see what's going on.

"Four Walls and a Roof: The Complex Nature of a Simple Profession" published by Harvard University Press, 2017. Image © WAC

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: With architecture?

Reinier de Graaf: Yes.If there is no revolution taking place every year, there's a major demolition happening. There is a major undoing of a revolution taking place with about the same frequency and this is a statement that I say without irony.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: You say that “architecture has become mere marketing and investment.” You also say: "In the face of economic needs, the architect is a largely powerless figure". Do you think that architectural ideas and visions are lost in the mass production of architecture shaped by different shareholders (politicians, bureaucrats, consultants, etc.)? These stakeholders have always been in the architectural production, so what is the different now?

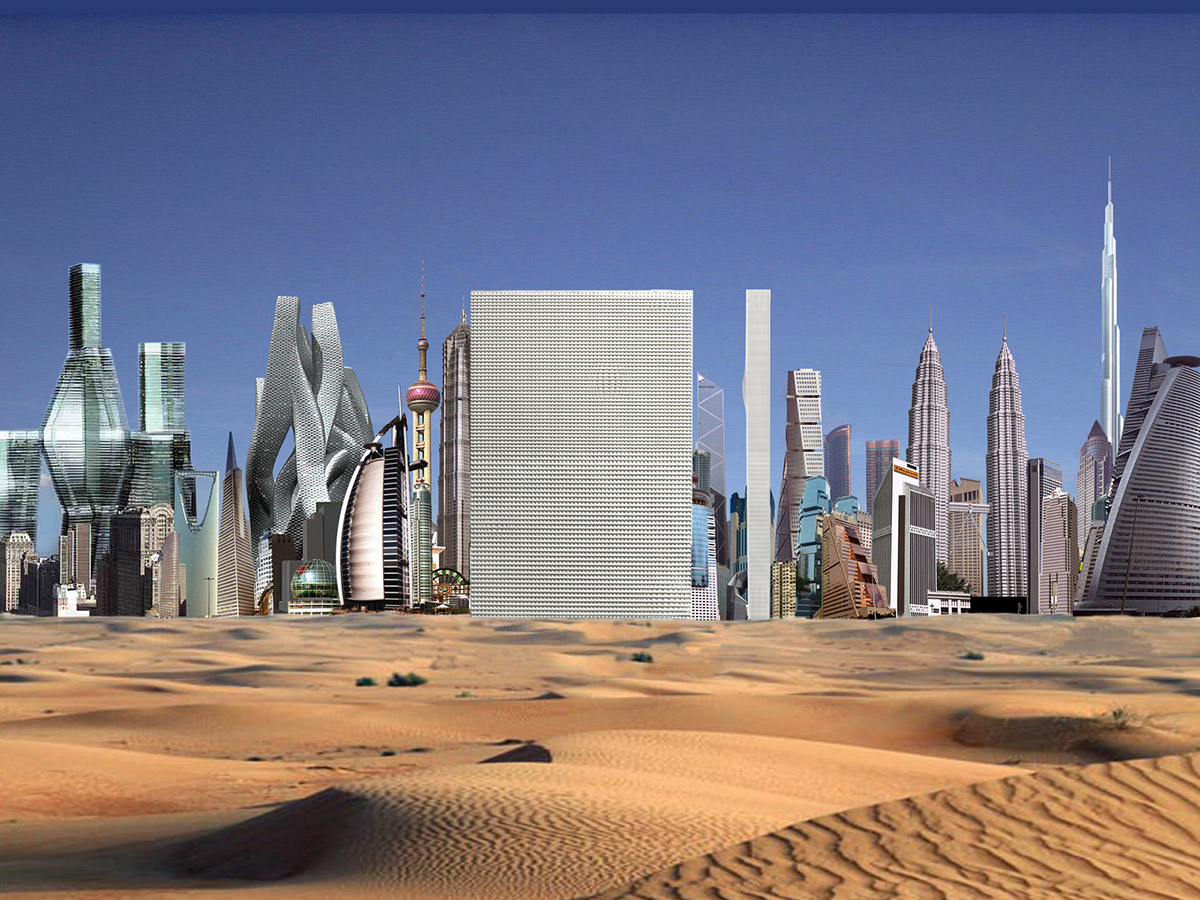

Reinier de Graaf: You can debate how crucial originality is to architecture because architecture is predominantly a form of imitation. It always has been; that's why you have styles and tradition. I think that originality is overrated and what in the essay you're referring to I write is that today's outburst of originality leads to a remarkable similarity. Even within our office, sometimes we come up with what we think is an ‘original’ idea and then we discover that something similar has been done before.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Are you trying to find similarities?

Reinier de Graaf: No. But it does happen to find that what one does is also done by ten other people. There is definitely a proliferation of certain ideas that hang in the air. You might think you’re ‘original’ but you’re actually part of a large army of creative minds.

Dubai Renaissance, a mixed-use high-rise building proposed for a competition in Dubai in 2006. Image © OMA.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Is this the copy-paste culture?

Reinier de Graaf: The copy-paste culture is precisely the result of the desire to be original. The more we strive to be exceptional, the more we collectively become unexceptional. In our Dubai Renaissance project we created a collage with the skyline of all 21st century skyscrapers. They are all exceptional but when you put a totally boring building in front of them, it's actually that boring building that becomes exceptional.

"The more we strive to be exceptional, the more we collectively become unexceptional"

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: In your book, you also criticize technology, the internet era, and media, in the sense that they doesn’t show the architects’ uniqueness, but rather the similarities between buildings or architects. Do you find that media and the internet prevent one from grasping original ideas? Isn’t media part of architectural production already?

Reinier de Graaf: Surely, it is. But I’m not criticizing technology. What I’m saying is that today's technological developments are of limited relevance for architecture and have limited relevance in form making. They make buildings more independent from their function or make functions more independent from buildings, which makes buildings completely interchangeable.

The invention of reinforced concrete, the use of steel, the escalator and the elevator had a huge impact on architecture. I don’t think that the digital revolution does that in the same way. Its rewards are altogether different. It recalibrates our relation to the existing more than it is an impetus for the new.

"Four Walls and a Roof" consists of 44 essays divided in 7 parts. Image © WAC

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: As someone who writes and teaches, how would you evaluate today’s architectural education? Do you find a gap between the current architectural education and the practice of architecture? Are they two parallel worlds?

Reinier de Graaf: It’s very hard to generalize, but I can speak about the American architectural education system and the only appropriate expression I can find is that it is: deeply f***ed. Students pay enormous amounts of money or have enormous student loans. The financial aspect is so prevalent that students become consumers of education. The huge sums they pay give them an enormous sense of entitlement. So, there is no desire to learn. Teachers have to be incredibly careful about what they say. It's the teachers that are being judged on their progress, not the students. Money interferes in the relationship between educational staff and students in such a way that the learning process has become impossible. The fundamental aspect of learning, which is the transfer of knowledge and the ability to criticize (and improving work as a result of critique) has become completely impossible. Any critique on student work can easily be labeled as harassment and potentially become the source of another #metoo case.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: How can we find the bridge between theory and practice?

Reinier de Graaf: Academia is completely disconnected from practice but academia is also completely disconnected from education. Every student and every teacher in America should read my book and then start all over again with their education.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: I insist on this question because it is particularly relevant for young architects.

Reinier de Graaf: Definitely. It is a big flaw not only for the architectural education but for architecture in general. It’s like you're working with a 50% handicap: you know the economy of construction but you don’t know the economic system that buildings end up being part of. As long as you do not acquire that knowledge, you are fighting your battles with one hand tied behind your back. That's the situation architecture is in and I think this has to change and it has to change fast.

(-end of transcript)

Top image: Reinier de Graaf © OMA