Submitted by Tarun Bhasin

Remembering 'In Bruges'

India Architecture News - Jan 19, 2020 - 05:17 11791 views

‘In Bruges’… is a movie about Bruges. It shows nothing about Bruges. It is set during Christmas in Bruges. And yet, it has nothing to say about it at all. But again, it is all about it, as the title suggests. It is a movie of ironies, where through simple contradictions memory emerges from the encasement of mentalism of its characters, and ingresses itself within their actions and emplaces itself onto the events that take place… In Bruges.

The shots open by presenting a layer of social dystopia in the 'otherworldly' images of Bruges creating an apparent conflict, giving a hint on the presence that Bruges will impose on the characters of the movie. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

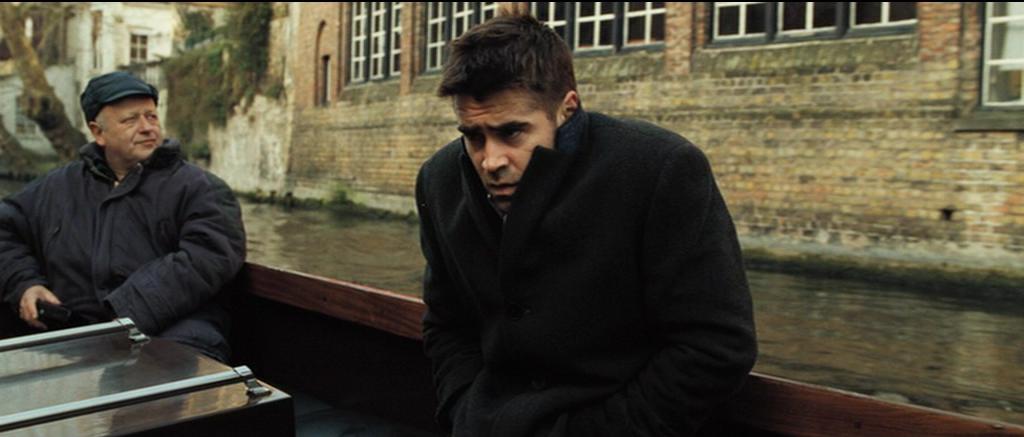

It is a story centered on three main actors, Ray (Colin Farrell), Ken (Brendon Gleeson), and their boss Harry (Ralph Fiennes). All three are hitmen, adding a layer of social dystopia in the 'otherworldly' (as described in the script by the writer and director Martin McDonagh) images of Bruges creating an apparent conflict, giving a hint on the presence that Bruges will impose on the characters of the movie.[1]

Harry has sent Ray and Ken to Bruges in hiding after a job has gone wrong. Thus, we enter the movie with the two characters recognizing the physical reality of Bruges awaiting judgement for their mistakes, reminding themselves and the viewers of their biases emerging from their past in London and Dublin. Ken finds the city quaint evident in the use of positive and idealistic factual descriptions of the city to convince Ray, “Bruges is the most well preserved medieval town in the entirety of Belgium, apparently” which through his statements seem more like an endorsement due to the abject mismatch with the situation the two characters are put into.[2]

The methods of the movie build on the very existence of Ken’s importance to Bruges being a preserved traditional medieval town, (in its artefacts, signs, symbology and language of a moral stance) and reflexively strip its identity bare and independent in opposition to its historic and religious roots. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

He takes Ray sightseeing along the city’s canals, lined with archaic buildings, and upon lanes of cobblestone paving onto the plaza with the Gothic church, despite the subtle-bitter winter and its sensuous freezing fog; Ray has much contempt towards the city’s weather, imagery and culture revealed in his overt remark “Ken, I grew up in Dublin. I love Dublin. If I'd grown up on a farm and was retarded, Bruges might impress me, but I didn't, so it doesn't.”[3]

There is a clear stance border lining the self from the other in Ray’s statement. More importantly, the movie helps us realize that the characters (and beyond the movie, people) have always occupied this stance. It is apparent in Harry's insecurity and apprehension about hearing anything negative about Bruges, and the constant reminiscing of his time spent during Christmas in the city once during his childhood.[4]

Conceived in the script as occurring exclusively within the canopy of Ray’s mind; viewers, throughout the length of the movie, witness this interest in simple pervasive mentalism of recollection being put in sharp contrast to the forms of memory to weave the actuality of memory of events happening in the present in Bruges. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

The plot of the movie is centered around recollections and summoning up of past experiences of the recent job gone wrong in visualized scenes (where Ray on his very first job as a hitman that happens to be a planned murder of a Catholic priest (Ciarán Hinds) in a church, accidentally murders a child who is praying with a confession note in his hand, a dystopia within a dystopia, adding layers to the conflictual and dystopic stance the characters imprint upon the memory of Bruges during Christmas time). Conceived in the script as occurring exclusively within the canopy of Ray’s mind; viewers, throughout the length of the movie, witness this interest in simple pervasive mentalism of recollection (that which often neglects and subjugates the presence of the other three forms of memory: recognizing, reminding and reminiscing) being put in sharp contrast to the other three forms of memory to weave the actuality of memory of events happening in the present in Bruges.[5]

This contrast reveals the very essence of the movie as a juxtaposition of all these mnemonic forms, which converge carefully in the script as a collection of modes or devices situated midway between the minds of its characters and their immediate external environment, also explored in an almost similar way in Italo Calvino’s city of Diomira, the very first in his assemblage of Invisible Cities.[6]

This contrast reveals the very essence of the movie as a juxtaposition of all these mnemonic forms, which converge carefully in the script as a collection of modes or devices situated midway between the minds of its characters and their immediate external environment. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

Hence, reflecting upon the story of ‘In Bruges’ as a will-to-utopia of Bruges enforced by Harry, (who eventually decides to kill Ray on moral and ethical grounds, and as it turns out, sent both the hitmen to Bruges where the retribution for the crime/mistake will be carried out on Ray by Ken), that is causing Ray and Ken to live in two worlds in this morality tale, ‘vertically’, between the divine and human and the physicality of Bruges in the center as a purgatory. We therefore, tend to re-visit the movie to re-witness the story of Bruges as the other half of the story of these men, as an investigation of morality in a postmodern world where traditional methods of right and wrong are hard to define, with Harry drawing another parallel with a kind of inflexible morality – the Catholic imagery that dominates the imagery of the movie and saturates the identity of the city ‘Bruges’ and the movie ‘In Bruges’ by inter-textual reference to the religion – drawing on the existential conflict between the historic values and ultimate reality of the Western world.[7]

To know more about the tool of 'Intertextuality' in storytelling, watch the video 'Intertextuality: Hollywood's New Currency' by Nerdwriter1 on YouTube.

While the story itself is a forceful placement of the notions of memory that reside within the faculty of the mind, primarily psychical, inward-looking, remaining tied to a mental pole; the scripts constant use of four places: the canal, the Gothic church, the hotel and the movie set; in a particular atmosphere and time of the year, accentuated by the background score; and centering of all mnemonic modes on them; brings about the movie a form of remembering that does not retain tenuous ties to the above stated mental pole of the movie’s characters, and instead constructs ways of remembering that manifest themselves ‘horizontally’ in an abiding and uncompromising placement… In Bruges.[8]

These can be classified into Body Memory, Place Memory and Commemoration, which are but the central subjects of inquiry of the essay and how their apparent relationship with the above four modes of mentalism in co-creation of its stories of Utopias or Dystopias, are essential in defining people’s perception towards cities, their signs and communal discourses that are necessary in interpretation of the idea of ‘A Good City’.[9]

To know more about how the movie constructs dialogue on morality in a postmodern context watch 'In Bruges: Morality in Dialogue' by Nerdwriter1 on YouTube.

WHY RAY IS FEELING COLD

Body memory is central to any form of memory, and we recognize it precisely at moments of its failure. The three main characters of the movie Ray, Ken, and Harry, are in a constant state of discomfort when they are out in Bruges, not because of their internal conflicts, but because of the cold weather.[10]

To say, the atmosphere of Bruges around Christmas time is only slightly colder than London or Dublin, but the very change of such a basic and taken for granted operation of the surrounding, which usually lies in the backdrop of any story of any city, is brought forth by the characters and how they choose to respond to it. The response, therefore, is not only an extension of their idea of the city but an insight into their nature.[11]

Hence, it is to be noted that in case of defining the city through the lenses of a populace, their body memory acts as a pivotal and presupposed notion in positioning their sense of instrumentality within the city. Its role in remembering the city becomes analogous to space and time.[12]

Ray’s frown and tensed shoulders evoke Kant’s transcendental aesthetics. They are a "priori in status, constantly working in one capacity or the other, never not operative". Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

Ray’s frown and tensed shoulders evoke Kant’s transcendental aesthetics. They are a "priori in status, constantly working in one capacity or the other, never not operative". Thus, if we must agree that the absence of the notion of space and time undermines the quality of human experience lived within it, then the absence of this body memory will cause complete devastation of the meaning of that experience altogether.[13]

In Bruges, portrays the body of its characters, subtly, as accusative objects, that contribute to their characters’ awareness in the city. They remember and live the city in and through and by their bodies, concretizing Marleau-Ponty’s claim of 'body as the natural subject of perception – point of view on point of views’ as one of the central themes defining the emotional state of communal discourse within the movie and beyond it.[14][15]

Within this discourse, habitual memories play the most pivotal yet understated role. Habitual memories are construction and re-enactment through repetition and regularity marked throughout the history of the body.[16] In the case of the movie, the actors being hitmen must be using guns. But, the moment of absence of guns (as per the absence stated above) becomes the points that reveal the tensions and vulnerabilities of the characters and mark the turning points in the plot. Viewers might first conceive that Ray is perhaps acting cranky due to the weather and accidental crime, only to later realize that they are mere tools to portray that Ray is inherently a brash and juvenile individual, in presence of the more seasoned and wise Ken.[17]

Thus, the habitual body memory is a limiting but powerful tool that ascertains the boundaries of a narrative within the city and works powerfully as a backdrop. In the words of Stravinsky, “In art (and in movies), as in everything else, one can build only upon a resisting foundation. . . . My freedom thus consists in my moving about within the narrow frame that I have assigned myself.”[18]

Ray wants to go back to London but is locked in the situations that arise due to his pursuit of Chloe (Clemence Poesy). The myriad tribulations are counter-conflicts played by the city on the characters that attract them into its web as the plot thickens, much like Calvino’s treacherous Anastasia. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

Habitual body memories are further supported by erotic body memories. Memories that show desire. In the absence of habitual memories, in the movie, (and in any narrative of a city,) erotic memories or memories of desire play a pivotal role in establishing the relationship between the characters and Bruges. This is revealed in Ray's constant desire to abandon exploration of the city and end up at a pub for some beer. Ray wants to go back to London but is locked in the situations that arise due to his pursuit of Chloe (Clemence Poesy). The myriad tribulations are counter-conflicts played by the city on the characters that attract them into its web as the plot thickens, much like Calvino’s treacherous Anastasia.[19]

But, the most important of body memories that act at the forefront of the construction of individual narratives in space and time are traumatic ones, which due to the limitations of the medium of exploration, (the essay and the movie,) can only be revealed through metaphorical import. The story exists because of the killing of an innocent child. Its physical metaphorical import from the past in the present is played by Jimmy (Jordan Prentice) who is a midget, dressed like a child. When he gets shot and killed in the same accidental fashion as the child had, the event brings the story to a full circle, linking the ironies of the past to the present events (and yet again we are reminded of one of Calvino’s manifestations, Melania).[20]

Thus, body memories are, the most effectual in construction of sequence and timings of narratives in a city, allowing continuity and reflexivity of characters of the city with a fullness of time apparent only through moments of their discontinuity or absence.[21]

hus, body memories are, the most effectual in construction of sequence and timings of narratives in a city, allowing continuity and reflexivity of characters of the city with a fullness of time apparent only through moments of their discontinuity or absence. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

THE GOTHIC CHURCH IS THE PROTAGONIST

“Memory is of the past” and primarily a temporal phenomenon. This is perhaps a ubiquitous logic elucidated in the entirety of the movie, which seems to juxtapose acts of remembering, and revive them in the present of the movie through images of its place and bodily movements of the characters that are inhabiting those places. Remembering in the movie seems fully preoccupied with the past of its characters.[22]

However, these revivals from the past are always seen through a veil of four primary places – the canal, the church, the hotel, and the movie set – combined to form the memory of Bruges. For this matter, the story never demands the exact repetition of these individual places or requires to reveal to the viewer their physical or cartographic nature entirely, as their elusiveness does not seem to matter in the largeness of the movie (and for that matter any narrative of any city).[23]

Every character drinks beer in the open café outside the Gothic church, ends up having conversation at the church’s doorway, most characters explore the porch and staircase of the church, and Harry and Ken have conversations and fights on the top of the church, and Ken jumps from the top of the church to his death in order to save Ray from Harry. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

But then, the movie itself is a monolinear phenomenon that moves forward with the dispersal and disintegration of time (as is life and any other narrative of any other city) made possible by events based on ‘clock-time’ such as when Harry calls or Harry arrives at precise times, or ‘public-time’ such as ‘dinner’ with Chloe. Memory here, is collective in nature, seemingly grabbing and unifying these individual explorations in place into a holistic and converging narrative.[24]

This duality allows Bruges to transcend from just a physical place in which the events are situated, to a point of view into these events, their characters and right into the memories from their the past that are reasons for events of the present happening in Bruges, but have no relation to Bruges. Thus, the characters seemingly occupy a portion of Bruges through which they undergo given experiences and remember them at the same time.[25]

This embodied existence of memory, of characters and places, opens onto Bruges, takes place in Bruges and nowhere else, and thus becomes of Bruges, defined in 'methods of loci' – the above four mentioned places. The characters are ‘inter-leaving’, ideal suitors for mediation between two different things – memory and place – constantly finding replacement to resituate remembered events of the past in the present – integral to both, the original experiences that they come to remember and also to the motion and time of the present that depends on Bruges.[26]

Characters are constitutive for the memory of place, as they, through the story, allow the memory of the places to include considerations that establish directionality, spatio-temporal distances and a sense of level. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

It is for this integration that the characters are constitutive for the memory of place, as they, through the story, allow the memory of the places to include considerations that establish directionality (route from the hotel to the canal to the roads to the church to the movie set), spatio-temporal distances (how every character drinks beer in the open café outside the Gothic church, ends up having conversation at the church’s doorway, how most characters explore the porch and staircase of the church, and Harry and Ken have conversations and fights on the top of the church), and a sense of level (when Ken jumps from the top of the church to his death in order to save Ray from Harry).[27]

Thus, Bruges is constructed as a kind of surface, a vessel, a container of all. A vessel that is a transportable place in memory and in time, but a place that is a non-portable vessel due to it being an actual physical cartographic entity. This appropriation of Bruges and its spaces, not according to their specific geometry or objective history, but by attuning it to the individuality of the characters turns it into a place that viewers sympathize with (revealed in a scene where both Ray and Ken are viewing paintings in a museum depicting the story of Jesus presiding over and emancipating the souls in a purgatory). [28]

This appropriation of Bruges and its spaces by attuning it to the individuality of the characters turns it into a place that viewers sympathize with. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

To say, the methods of the movie build on the very existence of Ken’s importance to Bruges being a preserved traditional medieval town, (in its artefacts, signs, symbology and language of a moral stance) and reflexively strip its identity bare and independent in opposition to its historic and religious roots. And so too with the Gothic church, which by an ensemble of all characters converging onto it, becomes an interpersonal being that in turn characterizes every aspect and gives back to the story a form of generality and helps develop the characters’ acts into stable dispositional tendencies (how the accidental killing of the child in the past happens in a church, how the confessions of the child are applicable to Ray’s character, how the bickering, the confessions, the repentance and also the romance happens with the church within or as the environ, becoming the ‘right-place’ to fit the unfamiliar characters of Chloe and Jimmy and many more, as the authors of their morality).[29]

Therefore, the Gothic church becomes the monument of Bruges and the movie by transcending its own historical and religious disposition to become a place for intensified remembering of all characters of the movie. It becomes the place of commemoration. All characters inhabit it as a common space within their events but remembering it through their own story, actions and relational aspects in it rather than the church’s or religion’s own objective historic or cultural events/texts/images (being set during Christmas but having nothing to do with it).[30]

Gothic church, which by an ensemble of all characters converging onto it, becomes an interpersonal being that in turn characterizes every aspect and gives back to the story a form of generality and helps develop the characters’ acts into stable dispositional tendencies. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

The Gothic church and its plaza are also in reality, and historically, the places of commemoration in Bruges, especially during Christmas. Thus, the movie, uses this superimposition of reality and fictitiousness as a mode of ritualistic enactment and re-enactment, making the movie inseparable from the memory of Bruges forever for the viewer (so do informal art, play, and collective events, in the memory of any city).[31]

In the end, it transcends from its link with Bruges by concluding the story in a movie-set within Bruges (part of the plot) and not in the Gothic church. (This is where Harry, in his quest for killing Ray, kills Jimmy the midget, who is an actor starring in the movie about Bruges being directed in the set; and thinks that he has killed a child and enacts the same code of honour (which he takes pride in) on himself by shooting himself, thus closing the story while showcasing ‘recollection’ as the prized paradigm out of all modalities for the popular discourse of remembering, where characters are mere triggers and observers of a force that is beyond them).[32]

The enactment of a movie set within the movie (a place within a place) contributes to formality for the sake of dramatization, bringing back the viewer to its fictitious nature, thus becoming a coherent and well-articulated whole. At the same time, this formality brings the spotlight back onto the body memory of its characters and serves to express and specify their emotions, and also channelizes the inherent nature of (any) movie to excess, thereby, commemorating its own story by communalizing the solemn act of accidental killing, in a ceremony, that is a movie set, that is in Bruges, but also independent of it (so that the movie is ‘In Bruges’ and avoids becoming ‘of Bruges’; exactly what all festivals and public ceremonies serve to do in a city) – thus, paying a fitting tribute to the city and its own title in a lasting way.[33]

Harry, in his quest for killing Ray, kills Jimmy the midget, who is an actor starring in the movie about Bruges being directed in the set; and thinks that he has killed a child and enacts the same code of honour (which he takes pride in) on himself by shooting himself, thus closing the story. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios

CODA

The notion of a good city and the transformation of urban local areas is indelibly dependent on understanding the positionality of its inhabitants. In Bruges reveals, details and analyses the philosophy and ontology of the very forms through which this positionality is constructed, and chooses to exist in a place and space-time, and is made apparent in a body's being and feeling. It is conclusive of three aspects: first, the bodily ‘withness’, although elusive, is the starting point for the creation of knowledge or understanding of knowledge in or of the body's circumambient world; second, being emplaced in the memory of the body and to remember it allows exploration of physical things, pathways, and horizons that thus, reveal the structure of containment and of environment - the ‘aroundness’ the body, and the body’s interests, morals, and ethics as discursive subjects within it; third, where these physical explorations overlap with other bodies is where commemoration occurs, not just as explicit ritualistic actions of the environ but interpersonal ‘throughness’ in close conjunction with the ‘withness’ of the body(s). The ‘withness, aroundness and throughness’ are the essential ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’ elements (mentioned in the beginning) that construct the reality of people and of places, and are indispensable tools in narrating the stories of their cities of existence, in trying to answer not what ‘A Good City’ might mean to them, but what and how any story around the theme and its constituents of inquiry should appear to be, without reserving any comment on what ‘A Good City’ is.[34]

The notion of a good city and the transformation of urban local areas is indelibly dependent on understanding the positionality of its inhabitants. In Bruges reveals, details and analyses the philosophy and ontology of the very forms through which this positionality is constructed, and chooses to exist in a place and space-time, and is made apparent in a body's being and feeling. Image Courtesy: Universal Studios.

Top Image courtesy of Universal Studios.

References

- Mumford, L. (2009). The Story of Utopias. 1st ed. London: Forbidden Bookshelf, pp.94-103.

- Mcdonagh, M. (2008). In Bruges. 1st ed. London: Faber & Faber, p.5.

- Mcdonagh, M. (2008). In Bruges. 1st ed. London: Faber & Faber, p.24.

- Heidegger, M., Macquarrie, J., and Robinson, E. (1962). Being and time. 3rd ed. Malden: Blackwell, pp.91-107.

- Casey, E. (2000). Remembering. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp.144, 145.

- Calvino, I. and Weaver, W. (2006). Invisible cities. 1st ed. Orlando, FL [etc.]: Harcourt, p.7.

- Mumford, L. (2009). The Story of Utopias. 1st ed. London: Forbidden Bookshelf, pp.1-7.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. and Smith, C. (1962). Phenomenology of perception. 1st ed. London: Humanities Press, pp.418, 426, 429.

- Casey, E. (2000). Remembering. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp.144, 145.

- Casey, E. (2000). Remembering. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp.146-163.

- Casey, E. (2000). Remembering. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp.163-180.

- Bergson, H., Palmer, W. and Paul, N. (1959). Matter and Memory. 1st ed. New York: Doubleday, pp.67-78.

- Parsons, C. (1992) “The Transcendental Aesthetic,” in Guyer, P. (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Kant. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Companions to Philosophy), pp. 62–100. doi: 10.1017/CCOL0521365872.003.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. and Smith, C. (1962). Phenomenology of perception. 1st ed. London: Humanities Press, pp.206, 178.

- Heidegger, M., Macquarrie, J. and Robinson, E. (1962). Being and time. 3rd ed. Malden: Blackwell, pp.95-107.

- Gadamer, H. (1975). Truth and method. 1st ed. New York: Seabury Press, pp.267-274.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. and Smith, C. (1962). Phenomenology of perception. 1st ed. London: Humanities Press, pp.82, 145-146.

- Stravinsky, I. (1960). Poetics of music in the form of six lessons. 1st ed. Cambridge, Mass.: Random House, p.68.

- Calvino, I. and Weaver, W. (2006). Invisible cities. 1st ed. Orlando, FL [etc.]: Harcourt, p.12.

- Calvino, I. and Weaver, W. (2006). Invisible cities. 1st ed. Orlando, FL [etc.]: Harcourt, p.80-81.

- Russell, J. (1981). How Art Makes Us Feel at Home in the World. The New York Times, [online] p.2. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/12/arts/how-art-makes-us-feel-at-home-in-the-world.html [Accessed 4 Dec. 2019].

- Aristotle. and Sorabji, R. (2012). Aristotle on memory. London: Bristol Classical Press, pp.445a 15.

- Husserl, E. and Churchill, J. (1964). The phenomenology of internal time-consciousness. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p.72.

- Heidegger, M., Macquarrie, J. and Robinson, E. (1962). Being and time. 3rd ed. Malden: Blackwell, pp.81-82.

- Yates, F. (1966). The art of memory. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, p.6.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1969). Visible and the invisible. Evanston: Northwestern U. Pr., pp.260-270.

- Casey, E. (2010). Getting back into place. Bloomington, IN: Indiana Univ. Press, pp.Ch. 4 and 5.

- Casey, E. (2000). Remembering. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp.181-194.

- nerdwriter1 (2016). In Bruges: Morality In Dialogue. [video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r_9mLu1kMA8 [Accessed 4 Dec. 2019].

- Casey, E. (2000). Remembering. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp.216-257.

- Husserl, E. and Boyce Gibson, W. (1962). Ideas. New York: Collier, p.181.

- Gadamer, H. (1975). Truth and method. 1st ed. New York: Seabury Press, pp.145 351F.

- Casey, E. (1975). Imagination and Repetition in Literature: A Reassessment; Yale French Studies (52). 1st ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp.249-267.

- Casey, E. (2000). Remembering. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp.258-260.