Submitted by Berrin Chatzi Chousein

Review: Tania Davidge on Architectural Criticism

Turkey Architecture News - Apr 05, 2013 - 22:30 5084 views

Tania Davidge reviews two discussion panels held in Melbourne and Sydney featuring US architecture & design critic Alexandra Lange, and considers the future of architectural criticism in Australia.

Above: ‘More than one way to skin a building’ panel (L-R): Michael Holt, Alexandra Lange, Karen Burns, Rory Hyde and Justine Clark. Image courtesy Melbourne University. Watch the video of the event here.

Last week the American architecture critic Alexandra Lange visited our shores. I attended two of the discussion panels: the first in Melbourne, entitled More than One Way to Skin a Building and the second in Sydney,Words and Buildings. They were two very different conversations about architectural criticism. Each event focussed on different aspects of criticism and the role of the critic, but both discussions provided points of simultaneity and insightful contributions to an ongoing larger discussion.

More than One Way to Skin a Building was chaired by Justine Clark with panellists Alexandra Lange, Karen Burns, Michael Holt and Rory Hyde. It was testament to Melbourne architecture’s long history of critical engagement that approximately 400 people attended a panel comprised almost entirely of architectural writers, editors and critics. The discussion was focussed and erudite, primarily exploring the opportunities and difficulties faced by the critic in the shift to digital publication platforms and what this means for the building of a critical community and a community for criticism.

The Words and Buildings panel, chaired by Lee Stickells, included a diverse range of panellists. Joining Alexandra Lange and Michael Holt in discussion was Sydney Morning Herald journalist, Elizabeth Farrelly and practising architect, John de Manincor. While the crowd was smaller, as was the venue, there was a sense of urgency and import to the conversation that was absolutely compelling. The conversation ranged widely and set its sights high with Lee Stickells invoking Robin Boyd in his opening remarks as he challenged the panel to explore ‘today’s opportunities for critical writing on architecture rather than bemoaning the loss of a golden age or waiting for the next Messiah’.

The issue of criticism and critique is a complex one and across the two conversations significant issues were raised. The role of the architectural critic is currently in a state of transition or crisis depending on who you are speaking to. Due to a myriad of economic, social and technological factors the media through which the critic communicates is undergoing seismic change and the role of the critic is perceived to be under threat. However, with every crisis comes opportunity and one of the primary questions for criticism is where this opportunity currently lies and what its agency is or should be.

So, what were identified as some of the pressing issues around criticism that we need to consider as a wider profession?

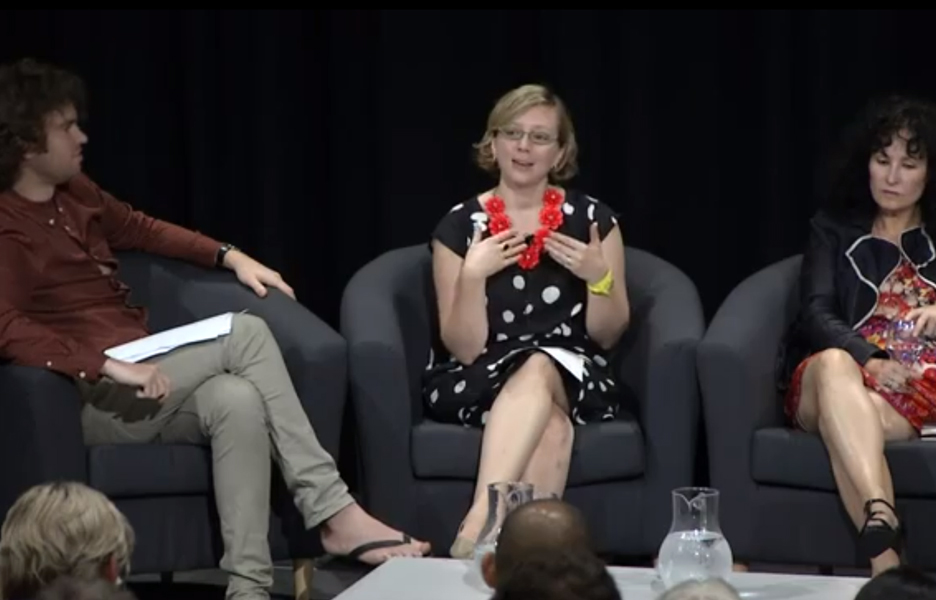

Michael Holt, Alexandra Lange and Karen Burns at the ‘More than one way to skin a building’ panel event. Image courtesy Melbourne University.

HOW DOES THE MEDIUM CHANGE THE MESSAGE?

The changing medium for architectural criticism is a key part of any contemporary discussion. The new online platforms may not have completely changed the message but they have made it more accessible. Accessibility has opened up the ways in which we engage with architectural criticism and the way critics engage with us. We can now participate in the conversation by posting our thoughts as an addendum to online articles and have conversations with like-minded people across the globe regardless of whether we have been introduced. As John de Manincor pointed out ‘If you think about architectural criticism as a form of debate, the digital medium suddenly opens up a whole new platform for those who aren’t professional critics. If you are interested and you want to have a voice it is there, instantly’.

As Karen Burns reflected, you can also create a more democratic platform where those left without a voice in traditional media have a space to speak. For Burns what is interesting is the ‘formalisation of the unsaid – what formerly didn’t have a voice in the public realm.’ In the digital realm she sees much more discussion of architecture from the bottom-up that has the potential to subvert dominant modes of criticism. Sites such as ‘ArchLeaks’ use architecture office gossip to expose the practices of well-known architectural firms and ‘Unhappy Hipsters’ and ‘F**k Your Noguchi Coffee Table’ critique dominant modes of architectural representation.

But what does the digital realm hold for the writer/reader? In addition to more traditional print publications Alexandra Lange has a Twitter account, a Tumblr account, she is addicted to Instapaper, posts photographs on Instagram, maintains a blog and writes for Design Observer. Each of these digital platforms acts in different ways: for example Twitter is for chatter and wisecracking and blogging is like a first draft. Each has different levels of authority – none of them have any editorial input with the exception ofDesign Observer. And all of them create communities of common interest that cross international borders. Each contributes in a different way to her practice as a critic and a writer and to the construction of an audience for her work. The digital realm allows her to be more experimental with the way she approaches her work, to get broader feedback and to explore opportunities for collaborative criticism.

Websites like ArchLeaks “reveal the hidden beneath the architectural studios” (image from archleaks.com)

WHAT ARE THE PITFALLS OF NEW MEDIA (OR WHY WE SHOULD STILL READ THE NEWSPAPER)?

Digital media allows writers and readers to participate in the same space. You can move from reader to writer simply by posting a comment at the bottom of the page. This participation reinforces online communities and blurs the line between the critic and the audience. Online communities are highly defined and, by definition, less diverse. The participant selects what they read according to their interests. In this highly self-curated space it is unusual to be exposed to views other than ones you are interested in. The newspaper, for example, read cover-to-cover exposes us to a wider range of views. In the paper we read about things because they catch our eye, things that we might never be exposed to online. It is important to remember that diversity leads to more robust conversation.

While the opportunities for criticism have multiplied in the shift online, every interesting moment is surrounded by an ocean of white noise. As Michael Holt cautions, ‘the blogosphere can be great. It can despatialise architecture entirely. But it also leads to a multiplicity of voices which can be either democratic or incredibly banal’. Although digital platforms open up the ability to take part in the conversation, for those who do not know how to navigate the terrain, they can be impenetrable in terms of orientation and content. For many this shift has removed architectural criticism from more publicly accessible forums and potentially leaves us preaching to the converted.

The manner in which we engage with online platforms can also be problematic. Lange points out that, on the whole, the Internet is a very positive space. Negative criticism, while not completely frowned upon, is not typically the way you are advised to build up followers. All criticism needs is what Lange terms a ‘little pepper’, to keep us on our toes. Although in defence of the overtly positive there is significant talk of architectural advocacy in the contemporary discussion on criticism. Perhaps we really do need more cheerleaders.

A pressing problem for the architecture critic is one which Elizabeth Farrelly succinctly identified: ‘To be frank the reason there is no criticism is because no one is prepared to pay for it.’ Which is easy to say but a more complex issue than it appears. Although the platform for criticism has changed traditional funding models do not appear to be keeping pace. With declining readerships for architectural publications and an audience that is used to accessing online content for free what are the new models that might fund quality criticism? The issue of economic constraint was engaged with across both panels, by more than one panellist, and is one for which no solution was provided. It’s a tough time to be a journalist.

Alexandra Lange speaks at the ‘More than one way to skin a building’ panel. Image courtesy Melbourne University.

HOW IS THE FORM OF CRITICISM CHANGING (OR ARE WE STILL ALLOWED TO TALK ABOUT BUILDINGS)?

Not only is the medium for criticism changing but the traditional form that criticism takes is also undergoing an overhaul. Rory Hyde observed that the assumption the building review is the foundation of architectural publishing has been revealed as false in the shift to digital media. It is a way of looking at architecture that is completely tied to the print media. Hyde links this shift in focus to an expanded definition of architecture which is no longer as closely aligned with the built object and where architecture is now being explored as a more diffuse cultural practice. For Hyde the change in media allows us to rethink what architecture criticism is – ‘it’s a culture, it involves the conversations, it involves the people, it involves the back-chat on Twitter and then, at some point, there is a building’. As the new media for architectural criticism have expanded so has the definition of architecture. Whether this is causal or coincidental is debatable, but conversations that were previously confined to the dinner table, the academic conference or the bar are being opened up to a much broader audience.

This shift in focus from the building review to a more open, democratic space can be political. Michael Holt believes we need to question the barriers of entry and that challenging the basis of traditional criticism – the showcase building review – is imperative. Currently Holt is interested in an approach that ‘traverses a body of work analysing a singular element. This displaces the singular architectural object, it removes it from its context and places it amongst a much broader debate’. The aim, in shifting away from the ‘hero shot’ approach to architectural criticism is to place less emphasis on architecture as a completed perfect object and through doing this engage architectural knowledge in greater depth and expose the processes of architecture to more discussion and debate.

While it is imperative that new forms of criticism are explored, Justine Clark reminded us that, whatever the form, it is important for the writer to remember that they are ‘staging a productive encounter with the building’. She goes on to say: ‘I don’t disagree with the boringness of the building review as a form but I am also reluctant to give it away completely. There is an opportunity in it and I think that opportunity is when the critic uses the building to open a discussion… The medium doesn’t determine the form. The medium opens up opportunity and closes down opportunity’. Perhaps the definition of what a building review is needs to change. The building review as a snapshot in time needs to be prised open in a way that stages more productive encounters with the architectural process, how architecture is achieved and what it is constrained by. While many international publications were mentioned at the panel discussions Australian archi-zines such as ‘Post’ are also addressing this issue with a focus on the building post-occupation. And, interestingly, AR is pushing the boundaries of the project review through exploring the notion of process, analysing buildings from concept to completion, in their new section Under Construction. Holt explained that there will be an online forum dedicated to showing documentary photography of the fabrication and testing of innovative products, this will then be shown in its construction stage in print, and finally in completion through a project review.

Architectural Review Asia Pacific magazine.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF THE CRITIC AND CRITICISM IN CONTEMPORARY DISCOURSE?

Three levels of criticism were addressed across the two conversations. There is the critic who holds a position of authority or expertise and traditionally mediates between the architect and the audience; criticism – which is the broader debate or conversation and critical thinking which audience member Donald Bates described in Melbourne as ‘not a job description but an act of creative knowledge which feeds back into the creative process.’

As there is more than one level of criticism there are also different audiences for criticism. The issue of public engagement was raised at both panels and is of particular concern in contemporary discourse. However, in order to have any broader effect we not only have to engage the public but also engage the architects. Good criticism and advocacy stems from a conversation within the profession as well as between the public and the profession. Bates cogently pointed out that, for him, the most influential critical texts were not written for the public but written for an architectural audience.

Elizabeth Farrelly made the point that the public debate requires vocal architectural voices but that we also need to have the capacity and the desire to communicate. Such abilities are driven from within the architecture community. Critical judgement, evaluation and communication underpin our practice and the creation of good architecture. Critics hold us to account, educate us to the process, and advocate the importance of these outcomes. The ability to think critically is important at every level.

HOW CAN WE ENGAGE THE PUBLIC IN A CONVERSATION ABOUT ARCHITECTURE (IS THE PUBLIC EVEN INTERESTED AND IF NOT HOW DO WE GET THEM TO PAY ATTENTION)?

One of the primary problems we have as a profession is that the broader public has little understanding of the architectural process, its limitations and also the opportunities it provides. Often the public are removed from the ideas and motivations behind the work. Currently engaging the public more widely in conversations about architecture is of particular concern to the profession. While public engagement is a rallying point that most agree needs to be addressed the real question is how we might achieve it. In an image-saturated culture where architecture is discussed infrequently in the newspapers and ‘architectural’ television programs focus on painting the architect out of the picture, how do we even begin to reach this broader public?

John de Manincor raised the importance of writing to the everyday practice of architecture. Perhaps this is where our communication with the public needs to begin. This type of mundane writing – planning submissions, fee letters, and our communications with consultants, builders and clients – is where we need to start communicating better. If we were serious about communicating with the public, right there would be a good start. After all not everyone is made to be a vocal architectural critic.

Lange believes in the importance of cultivating citizen critics – ‘people with the vocabulary that enables them to talk to architects and planners about their own built environment’. We need to give the public the tools to empower them to speak to architects and planners so that they do not feel constrained by what Lee Stickells identifies as rational ignorance – ‘when faced with complex issues it becomes ‘rational’ for people to remain ignorant of the complexity of those issues and all the kinds of knowledge they would have to gain to make a real difference in the discussion’. In addition, Lange says ‘we need more brokers who think of architecture as part of wider opinion – as part of economics, politics or just culture in general… [We need to make] sure architecture is part of these new institutions and gets on that list so that it is distributed with these other things’.

Alexandra Lange, Michael Holt and Rory Hyde all identify a new kind of critic that has emerged online – a critic that shifts the focus from architecture as built object to architecture situated in relation to a broader context. A critic that opens up the definitions of architecture and locates architecture in a wider field be it urban, political, social, cultural or economic. This new kind of critic looks at architecture in its widest context, broadens the audience for architecture and therefore exposes architecture to a larger public.

WHAT DO WE TAKE AWAY FROM THE DISCUSSION?

Perhaps, in the end, we should remember that criticism should be catalytic. It should change the way we think about a building or the city we live in. It does not have to be provocative but it should provoke a response. It should make us think about the spaces we inhabit and what we do as architects. It should open up a discussion, and that discussion should be open to interpretation.

Tania Davidge is a Melbourne-based architect, sessional academic at Monash University and RMIT, and director of OpenHAUS.

via Australian Design Review

http://www.australiandesignreview.com/features/29026-review-tania-davidge-on-architectural-criticism