Submitted by Berrin Chatzi Chousein

Chinese models focus on the quantitative aspect of urban planning, says Chris van Duijn of OMA

Netherlands Architecture News - Feb 12, 2019 - 01:31 8020 views

Chris van Duijn says new Chinese models are focused on the quantitative aspect of urban planning in terms of quality and most of these projects are very similar. The renowned architect argues that how these enormous urban expansions can be sustainable for the near future.

Speaking to World Architecture Community in an exclusive interview, van Duijn argues that designing a cultural building or masterplan in China is different than designing in any other country. And cultural shifts or existing parameters impact the ways they design buildings or masterplans but these can be rethought with some large-scaled operational models as OMA implemented in some masterplans.

Chris van Duijn, Partner at OMA and Director of OMA projects in Asia, talked about the recently completed and ongoing projects of the firm in the Asia Pacific region, as the firm expands its Asia portfolio with significant cultural projects.

The Taipei Performing Arts Center, the refurbishment of the UCCA in Beijing and the Columbia Circle in Shanghai are just a few projects that the firm is currently working on, alongside its retail and office complexes in Beijing and Shenzhen.

"What makes Asia interesting are, of course, the many opportunities to work on large-scale commercial projects," Chris van Duijn told World Architecture Community.

"But our aim is also to combine such projects with small scale projects and projects with a public or cultural character."

"Today we are working on around 15 projects in Asia from our Hong Kong office, of which half of the projects are under construction. So in the coming three years there will be many more new projects to reveal," he added.

OMA's new Taipei Performing Arts Center, which is among WAC's 10 hotly-anticipated buildings set to be completed in 2019. Image © Kevin Mak, courtesy of OMA

Chris van Duijn has been working as partner since 2014 in OMA and he is leading OMA’s various projects in Asia, alongside David Gianotten, OMA's Managing Partner. After joining the practice in 1996, the architect has been involved in many of OMA’s most renowned projects including Universal Studios in Los Angeles, the Prada stores in New York and Los Angeles (2001), Casa da Musica in Porto (2005), and the CCTV Headquarters in Beijing (2012).

Culture in China plays a very different role than in the West

Talking about the impacts of cultural domains in Chinese urbanism, van Duijn provides an in-depth look to explore how culture is copped with in new masterplans by focusing on the quality rather than the quantitative approach.

"Culture in China plays a very different role than in the west," said the architect. "For instance, the amount of museums per capity is in China much lower than in Europe."

"But the Chinese government has acknowledged this and therefore defined the ambition to make the cultural industry a main element of the national economy between 2016 and 2020."

"For instance, they defined that by 2020 there should be one museum for every 250,000 citizens, which implied that by 2020 China should have around 8,000 museums," van Duijn continued.

OMA completed the first part of the refurbishment of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, one of China’s oldest private museum for contemporary art, re-positioning the centre in the 798 Art District in Beijing. Image © Bian Jie, courtesy of OMA

Chinese models are really focussed on the quantitative aspect of urban planning

Focusing on the Chinese context in many aspects, the architect argues that the large-scale urban planning models in China are based on a more quantitative approach rather than the quality, and draws attention to how these urban planning models can be sustainable in the future.

"The Chinese model for urban expansion is extremely efficient. It is based on coordinated planning on many different levels and departments of local governments. Parameters are defined on a very high level," the architect explained.

"Essential for these masterplans is the control of numbers and the design of the infrastructure, which anticipates future conditions which may be still 20 years ahead."

"Such models have proven to be successful, as in the past decades the urban expansion has exploded. However, the Chinese model is really focussed on the quantitative aspect of urban planning, in terms of quality, most of these projects are very similar. The challenge I foresee is how sustainable these enormous city expansions are."

"Will they in 30 years time have similar issues to what we have experienced with large scale projects in Europe, built in the fifties-ies or sixties? Do these areas become communities?".

OMA's Columbia Circle transforms Shanghai's historic site with a vivid and colourful masterplan by protecting the rich and layered history of the centre. Image © OMA

OMA tries to design unique urban conditions based on authentic qualities

The acclaimed architect also explained how OMA approaches to these problems over the specific Chinese context. Van Duijn stated that OMA is trying to design unique urban conditions, based on authentic qualities which may relate to the history, topography or other opportunities within a certain context.

To support his argument, the Columbia Circle can be given as an example that is being as the part of the context. Partially being built in Shanghai until now, the project shows how the cultural characteristics are carefully layered within the existing buildings.

"It is a very challenging project as it is the first redevelopment project of our client, Vanke, and the culture of working with existing buildings is diferent in China," said van Duijn.

"Our approach to the existing architecture was to use the buildings as a canvas on top of which we added local interventions to increase their performance, structure or to comply with local regulations, or to improve the relationships between the buildings and the urban space by for instance making openings in facades or excavating parts out of the volume," he continued.

OMA's Tencent Headquarters is under construction in Beijing, China. Image courtesy of OMA+Unit

Apart from OMA's significant cultural buildings and office complexes, the firm is also working on small-scaled retail and exhibition design projects in Asia, with AMO, a think-tank of OMA. The firm completed the new Hundai's Genesis showroom in Seoul and its first exhibition design in Beijing - exploring different modes of selfie-culture.

The firm is currently working Hanwha Galleria department store in Gwanggyo Korea, and the design of two new towers for the department store group SOGO in Hong Kong.

Chris van Duijn is also leading the design of the Jean Jacques Bosc Bridge in Bordeaux; the construction of the Axel Springer Campus in Berlin and the Parc des Expositions in Toulouse.

In this exclusive interview, Chris van Duijn talks about the recent projects of OMA in Asia, including the UCCA, the Taipei Performing Arts Center, the Columbia Circle as well as with the importance of designing in Chinese context.

Scroll down to read the interview with Chris van Duijn:

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: You’re leading Asian portfolio of OMA. We see that OMA is expanding its cultural portfolio, alongside office projects, in many Asian cities. Could you please tell us about OMA’s recent upcoming projects that are under construction now in different cities?

Chris van Duijn: In the last 3 years we invested a lot of energy in our Hong Kong office, which has resulted in a very diverse portfolio of projects. A lot of our projects are located in mainland China, but we also work on projects in Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan and South Korea.

What makes Asia interesting are, of course, the many opportunities to work on large-scale commercial projects, but our aim is to combine such projects with small scale projects and projects with a public or cultural character. We work for instance on redevelopment projects: we just opened the first part of our smallest project, a new entrance for UCCA, a contemporary art institute in Beijing. At the same time our design for the Tencent Headquarters in Beijing, housing 10,000 employees, is being completed.

Today we are working on around 15 projects in Asia from our Hong Kong office, of which half of the projects are under construction. So in the coming three years there will be many more new projects to reveal.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: In recent years, there is a radical shift on Chinese urbanism, setting some new cultural policies, “new materialist” approaches and new networks of exchange, especially, by applying “Western” models in the networked space of globalism. From your perspective, how do you evaluate the recent demands on “art”, “culture” and “creativity” in Chinese cities, as part of urban planning processes or separate ruptures?

Chris van Duijn: Culture in China plays a very different role than in the west. For instance, the amount of museums per capity is in China much lower than in Europe. But the Chinese government has acknowledged this and therefore defined the ambition to make the cultural industry a main element of the national economy between 2016 and 2020. For instance, they defined that by 2020 there should be one museum for every 250,000 citizens, which implied that by 2020 China should have around 8,000 museums. In 2016 there were around 4,800 registered museums, so according to the numbers, there is still room for a few more official museums. So the challenge here is that the growth of the cultural sector needs to be in syncronized with the cultural development of the population.

But apart from the quantity, it is more interesting to focus on the content and the quality of the cultural domain. The contemporary art sector in China relies heavily on the private sector, the most succesfull contemporary art museums are all private, either set up by private collectors or supported by patrons. This domain is relatively new in China and only developed in the past 10-15 years, like for instance the UCCA in Beijing.

In many of the enormous city expansions, culture is integrated in the masterplan. However, often only the site and the GFA (Gross Floor Area) are defined. We were, for instance, approached by a client in Zhengzhou who were, as part of a large commercial development, planning to organize an architectural competition for a 70,000 m2 museum. As it turned out there was no collection, operator or any idea on content. We proposed the client to prepare a detailed masterplan for the area, based on culture, but much more diversified and as a much smaller museum. We convinced the mayor and party secretary and we are now preparing operational models for our client, thinking of different ways to program and manage a museum. Only then we will propose to work on a design.

OMA's UCCA Center in the 798 Art District in Beijing. Image © Bian Jie, courtesy of OMA

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: What are the main design principles of AMO/AMO to create a cultural city, district or region to make the area belong to the existing context, make it a part of daily urban life or make the cultural production sustainable in any Asian city, apart form the historical references?

Chris van Duijn: The Chinese model for urban expansion is extremely efficient. It is based on coordinated planning on many different levels and departments of local governments. Parameters are defined on a very high level. Essential for these masterplans is the control of numbers and the design of the infrastructure, which anticipates future conditions which may be still 20 years ahead. Such models have proven to be successful, as in the past decades the urban expansion has exploded.

However, the Chinese model is really focussed on the quantitative aspect of urban planning, in terms of quality most of these projects are very similar. The challenge I foresee is how sustainable these enormous city expansions are. Will they in 30 years time have similar issues to what we have experienced with large scale projects in Europe, built in the fifties-ies or sixties? Do these areas become communities?

It may be a very European conviction, but we are always interested in how to design unique urban conditions, based on authentic qualities which may relate to the history, topography or other opportunities within a certain context.

For instance, we are currently working on a masterplan for a new city expansion in Hefei, a provincial city with 5 million inhabitants. Located in the center of the 5 sq km area are the remains of a huge steel factory which is already partially demolished. But our client ackowledged that keeping those structures and making it actually the center of the project may give the city a unique identity.

So I think that this project is an example of the process which is happening today in China. As the largest cities in China, Beijing and Shanghai, are basically declared finished in terms of growth, there will be a focus on quality, both in the first-tier cities, but also in the second tier cities, which are still very much in development.

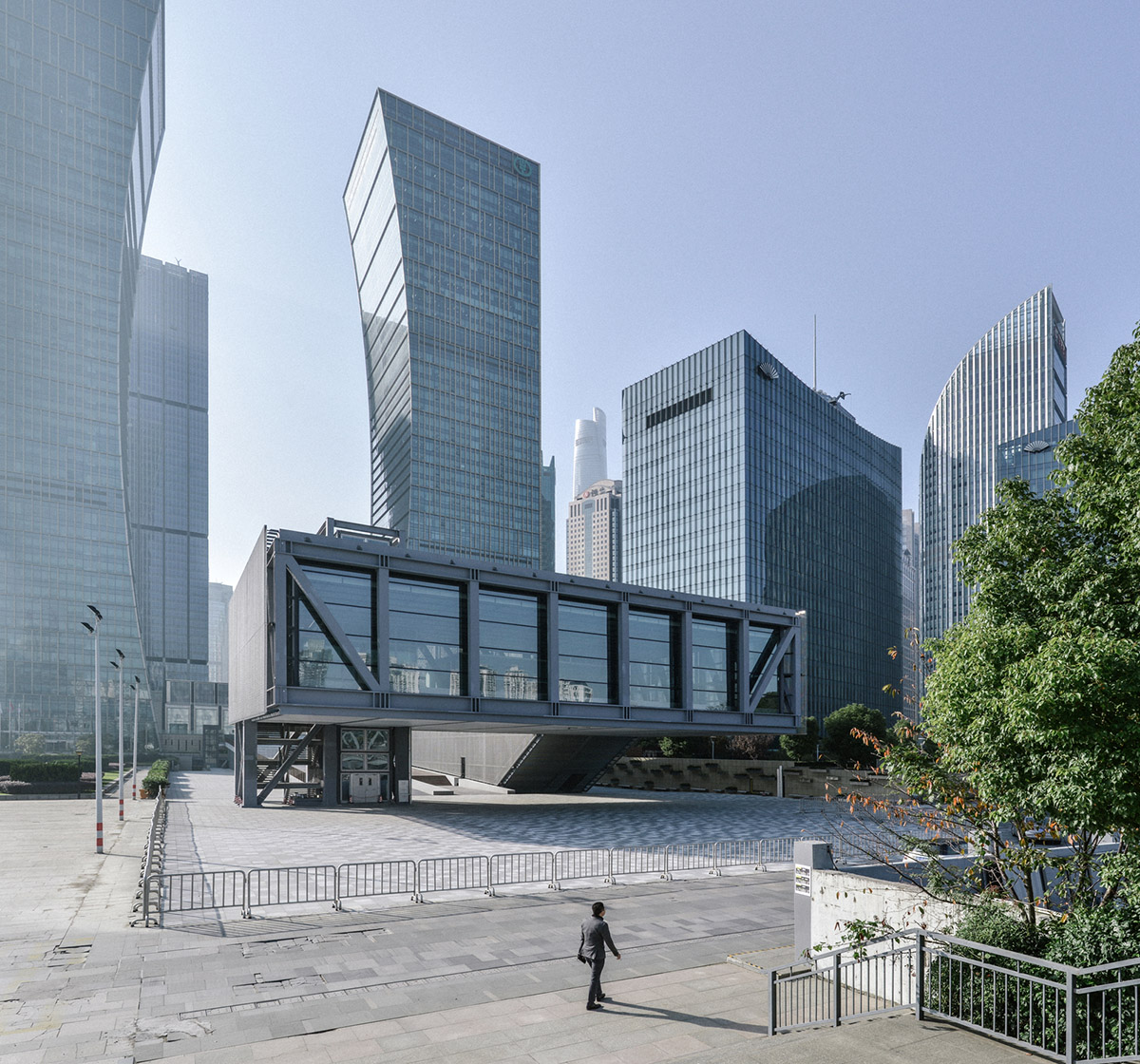

OMA’s first Shanghai project was made of a giant cantilevered box addressing to unfinished ship hulls. Image © Kevin Mak, courtesy of OMA

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Do you believe that "monumentalism" is still a key factor to increase the symbolic value of area or make a world-city building in Asian urbanism? I’m asking this because I see that most of recent projects of OMA seem like it avoids of "monumentalism" and uses "unobtrusive" forms designed according to pre-conditioned urban rhythms of daily urban life, apart from the Taipei Performing Arts Centre recently. Do you accept that OMA’s projects have slightly evolved into another direction?

Chris van Duijn: For years the most-used term in project briefs was 'landmark', describing the intention of a client or government to design a project that stands out from the rest, to be unique. This is not specific to Asia or China, it happened everywhere. The result of this ambition has provided very interesting projects, but more often it resulted in awkward shapes and facades, disguising a conventional building behind.

But currently, in line with the overall ambition of the national government in China, clients are more interested in innovation, both in architecture and urban planning. And although this sometimes still implies to build ‘landmarks’, the focus has gradually been shifting to the development of the performance of projects.This shift of focus makes working in China more appealing for us again as we are interested in developing new typologies.

In that sense, the Taipei Performing Arts Center project is consistent with the curent development.The building contains three separate theaters. We expose these ceremonial spaces to the outside instead of concealing them within a larger volume or roof. At the same time this constellation allows for something unique: as the stages of the three theaters interlock, we can transform these separate theatres into a single Super Theater by opening up the various stages, merging them into a single stage.

OMA's Columbia Circle masterplan which is partly built in the centre of Shanghai. Image © Frans Parthesius, courtesy of OMA

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: AMO/AMO recently completed an exhibition design in the vibrant 798 Arts District in Beijing and you have partly completed the Vanke Columbia Circle project in Shanghai. Could you please explain your design-driven agenda on these modest characters of the buildings on the Vanke Columbia Circle masterplan, as the site is combined with a rich collection of different spatial typologies? Why is each building telling us a different thing?

Chris van Duijn: For the Columbia Circle project we designed a master plan which is partially being built now. It is a very challenging project as it is the first redevelopment project of our client, Vanke, and the culture of working with existing buildings is diferent in China.

What we found most intriguing about the project is that the area has never been accessible to the public before. In the 1920s, it was a private country club for expats and later it become the home of the Biological Institute of Shanghai. As it was completely shielded off it developed autonomously from its surroundings. When I first visited the site it was like walking in a museum, as if time stood still, although it is located in a central part of Shanghai. The site contained structures from the 1920s until the year 2000, basically architecture of every decade was present, which made it a sort of exhibition of Shanghai architecture of the previous century.

The client was interested to add as much office area to the site as possible and left it open to us whether the industrial buildings should be re-used or demolished. In our masterplan we tried to transform these autonomous buildings into a coherent whole, while also introducing public program and access throughout the site. We selected the most useful of the in total forty structures for renovation, still representing all decades of the 20th century, and we proposed to add three new structures which would complement the available pallet of building typologies and provide the requested commercial floor area.

Our approach to the existing architecture was to use the buildings as a canvas on top of which we added local interventions to increase their performance, structure or to comply with local regulations, or to improve the relationships between the buildings and the urban space by for instance making openings in facades or excavating parts out of the volume.

Our concept was to turn this combination of existing buildings and new interventions into a single project, which does not focus on the contrast between old and new, or inside and outside, but on the whole project instead.

OMA is working on Unicorn Island, a new technology hub proposed for Chengdu in China. Developed as creative incubator, the island is organized into three rings. Image © OMA

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: When we think about the layered history of the site and the historical buildings, what were your major trajectories that you have followed on the site to make the area more attractive and liveable again?

Chris van Duijn: The structure of the masterplan forms the core of the project, it is close to a checkerboard scheme which allowed us to introduce a sequence of buldings and open spaces which always relate to all four sides. By designing these relations for each plot, either as a building or open space, we tried to realize a condition where visitors would always notice whether there is more to explore and therefore maximize the use of the site.

For instance, the original pool from the 1920s, actually the oldest existing outdoor pool in Shanghai, had an important role in the design. We planned to reinstate its original function as a pool and make it publically accessible again. We therefore opened the façade facing the main square, by turning the windows into glass doors, so that the pool became very visible and accessible to public. Unfortunately today the pool is not accessible for swimmers and the relation between pool and square is made undone as the entrance area was leased out to local F&B tenants.

In addition to improving the connectivity within the compound, we improved the porosity of the site by connecting the compound to its surroundings on all four sides. So far there was only one entrance from the street through a single gate. The new condition will naturally connect the compound with the urban fabric of Shanghai again.

The first phase of the project was opened to the public last year, however only parts of the original masterplan have been executed and some very important elements are still missing.

Areal perspective from OMA's Unicorn Island. The project has been selected as a winning entry in an international design competition last year. Image © OMA

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: In design process, do you see any difficulties between designing a single cultural building and changing the existing city fabric for a cultural project?

Chris van Duijn: I think that the UCCA transformation in the 798 district shows very well that this is possible. The project is very small, we reorganised the museum amenities, which were distributed in the existing industrial buildings, along the façade facing the street. This enabled us to remove some of the additons which were built in the past 15 years and transform the side walk into a generous forecourt which is fluently linked with the museum. Such a transformation of the building also affects the fabric of the 798 district, which is currently merely a congested ensemble of disparate architectural and programmatic elements.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Let’s move on another hotly-anticipated project on OMA: the Taipei Performing Arts Centre in Taipei. Could you give us more details about the progress of the building? When will it be completed and opened to the public?

Chris van Duijn: The works on site are ongoing. The façade is almost finished and most of it is already revealed. If all goes according to schedule the project should be completed in 2020.

(-end of transcript)

Top image: Chris van Duijn © OMA