Submitted by Berrin Chatzi Chousein

"Architects can help cities build inclusivity" argues Jeanne Gang

United States Architecture News - Jul 26, 2018 - 00:12 13566 views

Architects can play a role in making cities more inclusive, in part by designing projects that bring together different levels of housing and encourage social connection using multiple strategies, according to Jeanne Gang, Founding Principal of Studio Gang.

Discussing in detail MIRA, her high-rise project in San Francisco, Jeanne Gang emphasizes the importance of providing a mix of housing to help create democratic cities that serve all.

MIRA tower designed by Studio Gang. Image © Binyan

MIRA differs from many traditional towers as it combines market rate and below-market rate units in one building. Especially focusing on the context of San Francisco in this exclusive interview, Gang explains how to design a building in the prime part of the city with 40% below-market-rate units integrated with the market-rate units.

"It’s appealing to build in a city that values diversity and inclusion. I think San Francisco has created requirements for below-market-rate percentages because the city realizes the importance and shared benefits of having a mix of people living together," says Jeanne Gang.

MIRA, the 40-storey tower will be made up of a series of twisting bay windows that are reinterpreted from San Francisco's early houses. Image © Binyan

"The city of San Francisco has a real housing problem and they know they need to solve it. This approach might not work in cities where people can choose to live anywhere. When there are strong local parameters or demand, it provides a special opportunity to implement policies that bring below-market-and market-rate living together," Gang told World Architecture Community at the reSITE 2018 Conference.

"At MIRA, we have designed this mix to be realized without any segregation, showing that lower-cost housing and higher-cost housing can coexist."

Speaking to World Architecture Community at the reSITE 2018: ACCOMMODATE Conference held on June 14-15 in Prague, the architect shared her diverse body of work, including skyscrapers designed to create vertical communities in cities around the world. Jeanne Gang was one of the speakers at this year's reSITE Conference and Gang made a persuasive presentation on how architecture can be a major mechanism to build beneficial relationships among people and with their environment.

On the other hand, Gang also claims that architects can use different strategies to bring alternative solutions to the issue of housing.

"We can also think about how to work on an issue without having a client, for example. One strategy I’ve done in my practice is to develop research ideas independently, and then try to find a client," she added, as related to her working method at Studio Gang.

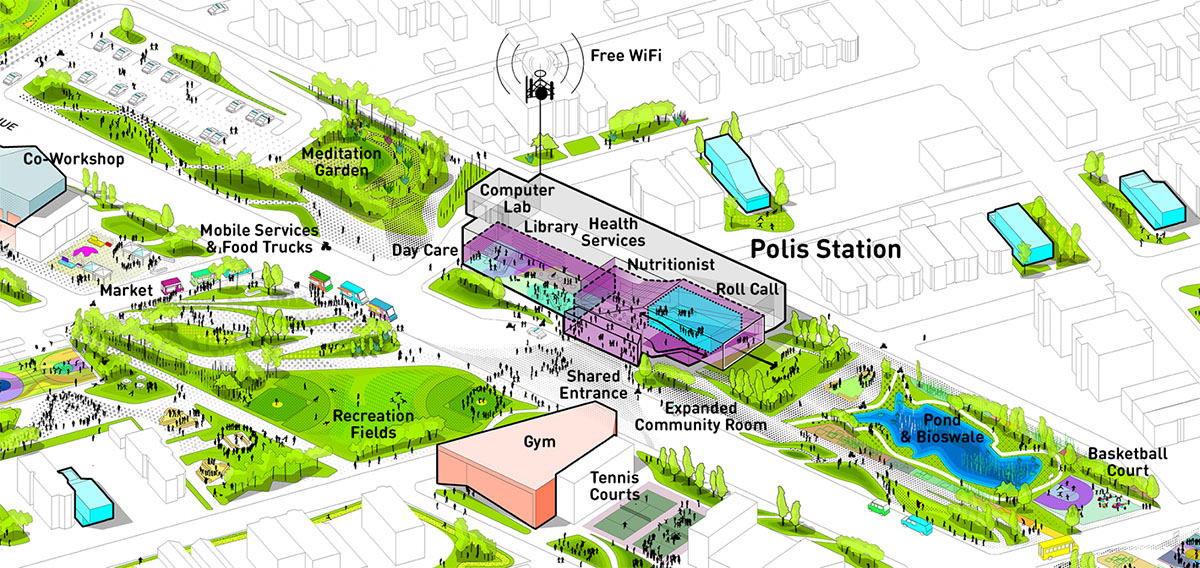

Studio Gang's Polis Station proposal in Chicago (ongoing project). The diagram shows how spaces in the police station and civic assets in the surrounding neighborhood can be reconfigured to accommodate new community programming. Image courtesy of Studio Gang.

Gang’s Polis Station project in Chicago is proof that this model can work.

"We researched the history of police stations and tried to imagine a new kind of police station that is more oriented to the communities they serve and where there is more everyday, positive interaction between police officers and neighborhood residents. We designed that project to respond to the concerns about violence between the police and the community in the United States," she continued.

Begun as a research project for the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennial, a portion of the project’s design vision was realized as an architectural intervention in partnership with a police station in Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood.

Solstice on the Park has recently been completed. Image © Tom Harris, courtesy of Studio Gang

Studio Gang produces different types of projects, ranging from urban design, interior design, and exhibitions to research. Gang's practice is based on expanding conventional boundaries for both the design process and project typologies in a broad sense. Jeanne is passionate about taking a broader approach to sustainability, exploring new potential for building materials and methods,and seeking opportunities to increase biodiversity in cities.

Her interdisciplinary and strong material approach come from her diverse educational background. Gang received her Bachelor’s degree in architecture from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1986, and in 1989 she studied urban design—an interdisciplinary program combining landscape architecture, urban planning, architecture, and engineering—as a Rotary Foundation Ambassadorial Scholar at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich. She earned her Master’s degree in architecture in 1993 from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design.

After working with OMA between 1993 and 1995 as a lead designer and project architect, she established Studio Gang in 1997. Studio Gang now has offices in Chicago, New York and San Francisco.

Studio Gang's City Hyde Park apartment building completed in 2016 in Chicago. The building features many irregular 'patelliform' balconies on one facade of the apartment. Image © Hedrich Blessing

Honored widely, Gang was awarded a MacArthur Foundation "genius grant" in 2011, as well as an Architecture Design Award from Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum in 2013 for her practice. More recently, Jeanne Gang was named the 2016 Architect of the Year by the Architectural Review. In 2017, she was honored with the Louis I. Kahn Memorial Award, made an honorary fellow of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, and electeda fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Most recently, she was awarded the Marcus Prize by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Architecture and Urban Planning in partnership with the Marcus Corporation Foundation, a prize given to architects who have "a trajectory to greatness."

Entrance to the Proposed Gilder Center: A rendering of the entrance to the proposed Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation from Theodore Roosevelt Park. Image courtesy of Studio Gang

Gang's many buildings currently under construction including a twenty-six-story residential tower in Chicago; MIRA, a 400-foot-tall residential tower in the heart of San Francisco (2019); Vista Tower, which is anticipated to be the third tallest building on the Chicago skyline when complete in 2020; and One Hundred in St. Louis, a tower with 316 residential units as well as retail, amenities and parking, due for completion in 2019.

In addition, 40 Tenth Avenue, an office building on the High Line in New York City, uses incident sun angles to carve away from the allowable zoning envelope to prioritize views and light between the High Line Park and Hudson River.

The Vista Tower, which is anticipated to be the third tallest building on the Chicago skyline. Image courtesy of Studio Gang

The studio is currently working on three major cultural projects—in New York, San Francisco, and Brazil, respectively. The Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation will be a curvaceous addition to the American Museum of Natural History and is one of the most hotly-anticipated projects of the firm and expected to complete in 2020.

The new campus for the California College of the Arts in San Francisco will bring together the currently separate Oakland and San Francisco facilities in an indoor-outdoor campus of art-making facilities and dynamic landscapes.

Finally, Studio Gang is also working on the new United States Embassy in Brasilia, Brazil. The new design will be situated on the existing Chancery complex within the city’s "Diplomatic Sector" near the seat of the Brazilian government. The project will rebuild the compound and provide facilities for the Embassy community.

In this exclusive interview, Jeanne Gang explains her design strategy on projects of different scales, her material approach, and her interest in housing and the design of vertical communities that shape the future of cities.

Read the full transcript of our interview with Jeanne Gang below:

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: This year reSITE’s theme is ACCOMMODATE, referring to the future of housing, affordability, new financial and urban regeneration models. I must say the alternatives that are brought by architecture must be far beyond the most basic needs for housing for people living in every class. In addition, there are many inputs in the design process we need to think about, like the financial model of the building, municipal authorities, social and economic factors of the city. But, where exactly does the role of an architect start in this complexity so that many people can live in the houses they choose?

Doesn’t it begin with a discussion that is created between the architect and the client concerned with the concept of the first project? What is the basic problem here before discussing the concept of the project at the earlier stages?

Jeanne Gang: Housing projects are different around the world, but at the moment, most of our residential work is based in the United States. Many U.S. cities have legal requirements about how many market-rate or below market-rate units need to be in a building. For example, we’re working on a residential tower in San Francisco called MIRA and according to the city, it's required to have 40% below-market-rate units. And at MIRA, we made sure that the below-market-rate units are integrated with the market-rate units in the same building, and that social spaces and amenities are designed to bring people together. So, in cities with local regulations, the first strategy for architects can be to provide housing at different levels. We need to work with cities to take a holistic approach, as a matter of democracy and policy, to ensure that more affordable housing isn’t treated as a different component of the city.

"We can also think about how to work on an issue without having a client, for example. One strategy I’ve done in my practice is to develop research ideas independently, and then try to find a client"

MIRA differs from many traditional towers as it combines market rate and below-market rate residences in one building. It’s appealing to build in a city that values diversity and inclusion. I think San Francisco has created requirements for below-market-rate percentages because the city realizes the importance and shared benefits of having a mix of people living together.

At MIRA, we have designed this mix to be realized without any segregation, showing that lower-cost housing and higher-cost housing can coexist. The city of San Francisco has a real housing problem and they know they need to solve it. This approach might not work in cities where people can choose to live anywhere. When there are strong local parameters or demand, it provides a special opportunity to implement policies that bring below-market and market-rate living together.

We can also think about how to work on an issue without having a client, for example. One strategy I’ve done in my practice is to develop research ideas independently, and then try to find a client.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Are you the first studio doing this?

Jeanne Gang: I don’t know. It is a way of operating as an architect with more agency, not waiting for a client to come and hire you. We have done this with a few projects, and it works because you are not bound by certain rules—you set the parameters. For example, with a project called Polis Station, we researched the history of U.S. police stations and tried to imagine a new kind of police station that is more oriented to the communities they serve and where there is more everyday, positive interaction between police officers and neighborhood residents. We designed that project to respond to the concerns about violence between the police and the community in the United States. There is often a lack of trust between those two, so we wanted to explore if design could play a role in building trust and improving that relationship. Since we did the project, so many communities have written to me to say they want to do something similar in their city. And Studio Gang has been hired to design other types of civic projects in other cities, as well, such as New York, Memphis, and Philadelphia.

Collections core: The five-story high, 21,000-square-foot, glass-walled Collections Core will be both a critical resource and a spectacular feature of the Gilder Center, revealing the specimens and artifacts that scientists use to investigate and answer fundamental questions, identify new species, and formulate new research questions and directions. Courtesy of Ralph Appelbaum Associates.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: I have heard it for the first time, it’s interesting, but what happens if you can’t find a proper client? Because you need to think about a financial model of the project or you have to put a general vision.

Jeanne Gang: This is a way of thinking that’s more like an entrepreneur. As architects, we should ask: If a certain project model doesn't exist yet, how can a client come to understand it and become interested in it? For example, we can propose a building in a disused or an abandoned site to demonstrate the potential of that place. It's a way of operating that reveals opportunity and possibility, that brings new models to the table.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Is it really working?

Jeanne Gang: The reason we’re doing it is to help expand peoples’ thinking. If the ideas resonate with others, then we can find a client to work with to keep pushing those ideas toward realization, testing them in reality. It's a way of working that’s more like an activist, or a provocateur, and that is the role I would like to see more architects taking on.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Do you think that any architect should propose an extra function, program or alternative models, alternative units that can be rented and sold at lower prices to a community living in that environment? What is the basic architectural component that he/she needs to think about it to create alternatives in the existing fabric?

Jeanne Gang: If we’re working with a developer, they generally have a model that they want to use. In fact, it is based on their research on the specific market and what's desired in that location. What we can do is to help them to imagine new kinds of shared spaces, new kinds of units that are more adaptable or flexible. So, we often times bring ideas to our clients to see if we can increase the amount of variety in the project.

Aqua Tower completed in 2010 in Chicago. The rippled tower includes a hotel, offices, rental apartments, condominiums, and parking, along with one of Chicago’s largest green roofs. Image by Steve Hall © Hedrich Blessing

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: I’m asking this because I would like to know if there should be a general vision that every architect has to follow? Do you always have flexibility to play with the program?

"In the future, I think there will be more variety in the field, more architectural entrepreneurs, and more architects will also become activists"

Jeanne Gang: If a project comes in, we always ask ourselves: What is interesting about it? How can it be more potent? What is the main question of this project? What is it trying to address? Then, we can create a stronger brief together with the client that also addresses some ofour own interests. There are many different ways of practicing architecture now. In the future, I think there will be more variety in the field, more architectural entrepreneurs, and more architects will also become activists. It’s important to have a whole spectrum of practice.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Studio Gang is best known for its various skyscrapers designed across Chicago, the U.S. But the studio’s approach is much more about focusing on creating "communities" in high-rise buildings, as well as low-rise buildings. How does the studio describe the notion of community in the skyscrapers? It is very difficult and controversial issue to create a community in high-rise buildings because their infrastructural models are very static – you just go up and down via vertical circulations. How does the studio works on that to create a balance between the existing buildings and the new building, as well as creating a social coherent within the new building itself?

Jeanne Gang: You’re correct, high-rise buildings can be very insular and focused on privacy, with people coming up and down by elevator so they never have the opportunity to see and get to know one another. To open up social opportunity, it is important to think about the outside of buildings. It is also important to think about the neighborhood and the kind of spaces where communities come together that can be provided in the block, not only in the tower.

I’m really interested in using the exterior of the building to create semi-public spaces, where balconies act like porches or thresholds that you can inhabit. That is an important part of developing the social space in high-rise buildings. How can we use the exterior of the building to create a place where you can see and spend time with your neighbors, and a place where you can make visual connections to other parts of the city? It can be about having a conversation on the balcony; it's also simply about making visual connections to other people. Moreover, in the interiors, having more shared areas throughout the building is key to designing for social interaction. A lot of low-rise buildings aren’t social, either, because they are designed with private garages, private front doors and private interiors—a lot of people don't even have neighbors. I believe it’s critical to create more opportunities for people to come together and connect with one other, in order to form stronger communities and make people aware of their environment. Eventually, this can lead to a better world.

"One Delisle" will be the first residential tower of the firm built in Toronto. The 51,049-square metre mixed-use tower, reaching at 158 meter, will include 263 residential units as well as green terraces. Image © Norm Li

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Many of your buildings are currently under construction, like 40 Tenth Avenue in New York, MIRA in San Francisco, Vista Tower in Chicago and many of them are also in design process. I think, each of them is designed by integrating a new technology and new materials, but beyond its appealing aesthetic, what are the first design strategies of the studio to make that skyscraper a part of the existing urbanization in the city fabric?

Jeanne Gang: We always try to give our buildings a sense of human scale, so that they aren’t monoliths. For instance, glass can be used in a way that breaks down the scale of the exterior to make it relatable to pedestrians. In almost every large building, we use some element to break down the scale—it might be at the scale of the balcony or at the scale of the floor slab.

The other part of your question is more about the planning process. We can start out with a framework plan, whether we design it or inherit it: where will the high-or low-rise buildings be? But it’s also key to think about creating flexible spaces that will enliven the neighborhood in a more spontaneous way—places that are able to host events and pop-up activities. With our Nature Boardwalk at Lincoln Park Zoo project, a public park, we did this by creating a flexible pavilion that’s linked to the boardwalk. The pavilion is a focal point on the 14-acre site and it’s designed to serve a lot of different purposes that give life to the city, from educational programs to yoga classes.

Studio Gang's 40 Tenth Avenue will be built by using angles of the sun with gem-like facade. Image © Timothy Schenck, courtesy of Studio Gang

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Do you always communicate with the existing communities you’re working into create better options, or alternatives or to make the design process more transparent?

Jeanne Gang: Yes, if it is a public project, for sure. If it is private project, it is more dependent on the client. To demonstrate the benefits of working with the community, we always try to show the various ways that we can do this kind of engagement—there's a spectrum of different ways to do it. I find that if you engage the community earlier in the design process, it usually benefits the project because people will be aware of it and can play a role in shaping a more meaningful outcome. We're not always the main decision maker on some issues, and so we always have to respect the client’s decision on what becomes public.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: How does the Studio Gang manage the use of technology in its buildings? How do you create a balance between the technology-driven approach and the use of nature?

"Technology can help us design a project that works better with nature"

Jeanne Gang: They're not opposing approaches. Technology can help us design a project that works better with nature. For example, we are interested in using glass in our buildings, but are very intentional with its use because it is a very difficult material for birds—up to 1 billion birds die each year in the U.S. alone due to colliding with glass they can’t see. I don't want to kill birds with my buildings. So, we've worked with different companies and technologies to create glass that is more visible to birds but still invisible to the human eye. We also use technology to make our buildings more energy-efficient in various ways. I don't see nature and technology as being in conflict—in fact, they can reinforce one another. I’m especially interested in technologies that are helping amplify our environmental approach.

The Arkansas Art Center is being developed as renovation and expansion project in Little Rock, acting like an insertion into the existing fabric of the building that extends out to the north and south into pavilion-like spaces. It is expected to complete in 2022. Image courtesy of Studio Gang.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: In your buildings, you love to use the new materials or testing the new materials for the new tectonics, especially in your skyscrapers’ facades. Does the studio conduct a specific research on the use of new materials? And, Are each material tested in the construction process to understand their reflections on the spaces?

Jeanne Gang: Yes, it’s true that I like to express the qualities of the material and to push its structural capabilities. With steel or wood, I’m interested in their flexibility, bendability. That means wood, for example, can be used in tension—which people usually don’t think about—to create curvature. By contrast, concrete is more fluid and mineral, so I’m interested in exploiting those kinds of qualities. It can be cast into different forms that are fluid, for example, or it can be layered.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is one of your highly anticipated projects to be completed in New York City. I see a radical formal difference and approach, compared to your other buildings. It looks like a cave compressed between the two existing edgy buildings. I see that for the first time Studio Gang has designed something that is so fluid and interacting building. How did the project have such a special and distinct architectural language? Is it derived from a project brief? What were your major considerations to interact with the two existing buildings?

Jeanne Gang: It actually fits in with our other work very well. To begin, it was shaped by its specific program. This project is all about flow—because the museum consists of many different parts (far more than two) that have accumulated over time, its circulation is very constrained. Our addition creates about 30 new connections to the old building. To echo this connectivity, we wanted to express the flowing qualities of concrete.

Moreover, we wanted to get visitors excited about the discovery process of science. The US is ranked behind many other countries in terms of science education, so there's a real need to get youth excited about careers in science and the science itself. To heighten museum visitors’ experience of discovery, the building acts like a canyon you can explore, where you can see things in other areas and figure out how to get there to learn more. This canyon-like architecture will be achieved with a special type of sprayed-in-place concrete construction called shotcrete. Essentially, we'll build rebar cages and then blow the structural concrete into it. Shotcrete has mainly been used in infrastructural projects but not yet in such an architectural, finished way, so this aspect of the project is also an exciting innovation.

In that way, as well, I don't think the AMNH expansion is in contrast with the rest of our studio’s work. The design developed from working with material and figuring out a new way of using it that is both structural and expressive, just like our other projects. For instance, the Aqua Tower’s slabs are structural and they extend out past the building; they are fluid in form because they were cast in concrete. When you see the building from the ground, you sense a quality of movement—it speaks about dynamic forces; it can help you see the city in a new way.

(-end of transcript)

Top image: Jeanne Gang, courtesy of Studio Gang