Submitted by Megha Balooni

"...Realise that in the end we are all the same" - Interview with Anna Heringer

India Architecture News - Sep 09, 2020 - 19:58 8631 views

In continuation to the previous article Significance Of Materiality In Architecture, this series of interviews seeks to push the conversations surrounding materiality and its influence to shape the vision and and final design of projects, regardless of its scale and scope. Beginning the series with German architect Anna Heringer, who believes that the world is not changing with one big decision but it is changing with every day smaller decisions, we try to understand her design idea and the process in this conversation.

Megha Balooni: The most successful development strategy is to trust in existing, readily available resources and to make the best out of it instead of getting depended on external systems. What has been one of the best project memories which can support this?

Anna Heringer: The answer to this might be every project that I have built with mud. It is amazing how one can dig it and use it. People bring in the material by carrying it. The mud itself is for free but you invest in the people that bring the material and that helps build the material. It is fantastic if you have to repair something, one can do it easily by just adding water. You can recycle it a million times without any loss of quality. It is fascinating yet the same regardless of whether one is in Bangladesh or Europe or anywhere in Asia or Germany.

We just built an altar in a very famous Cathedral in Germany where there is a lot of gold and precious material in the background, designed by a well-known Baroque architect. It looked symbolic of what our society has become; we are not lacking in material but we lack in good relationships and the sense to well utilise the same. For our team to build this altar, we thought of bringing in not any fancy kind of sculpture but to bring in the material- the mud which, for us, is more precious than the gold. It is the Earth which gives us food, a space to create our shelter and be our habitat. But gold- you cannot eat it; it has no life! In that sense, Earth becomes much more a precious resource for us. So, we brought in the Earth and then the community started ramming and building their own altar in this absolute sacred space. With the kids coming in as well as the elderly people getting involved to help, brought the same feeling as for one of our projects in a village in Bangladesh.

Wormser Dom's Sanctuary Interiors (Studio Anna Heringer). Image © Norbert Rau

Wormser Dom's Sanctuary Interiors (Studio Anna Heringer). Image © Norbert Rau

That is the nice thing for me - to realise that in the end we are all the same.

We have to take care of the Earth, our planet. We all, equally, long for good relationships and meaning in life implying that we are somewhere the same. Somehow, all that translates through a thoughtful building process, when you build it with the right material and are able to involve a lot of people and eventually, give meaning to the project.

Megha Balooni: Low-cost construction is one of the strongholds of your organisation. Could you share some challenges with material selection for a project with such a concept?

Anna Heringer: Sourcing the material is never difficult for us- just ask the farmers! They know the soil and are able to guide really well.

But what is difficult is to convince clients to work with mud because it somehow has this image to be a material for the poor and being old fashioned, and I absolutely disagree with that image. For me, it’s a heritage.

I believe this image hails from the Colonial times but it had not been like this earlier. The Colonialists shipped out all the beautiful goods from the Indian subcontinent and then on their way back, because the sailing ships would have been too light to sail, they must have brought building materials such as industrialised and baked bricks back with them, manufactured by using coal. Back in India, they would build using baked bricks, projecting this distinction of being someone different in order to create a difference between themselves from the regular masses. And of course, then the missionaries came followed by the engineers and they all built without taking into consideration the local climate and the materials and resources already available. The incredible and rich culture, the wisdom embedded in creating the previous structures, was absolutely lost.

The next step was the birth of the cement industry.

Whenever I’m landing in Dhaka, the first thing which pops up is all these advertisements for cement, steel and aluminum, and air conditioning. It is a known fact that when one builds using these industrialised materials, there would be a heavy need for air-conditioning, as opposed to mud construction which does thermally well. But since this kind of influence has existed for so many years, it becomes very difficult to unlearn.

Look at the movies- the hero does not live in a mud house!

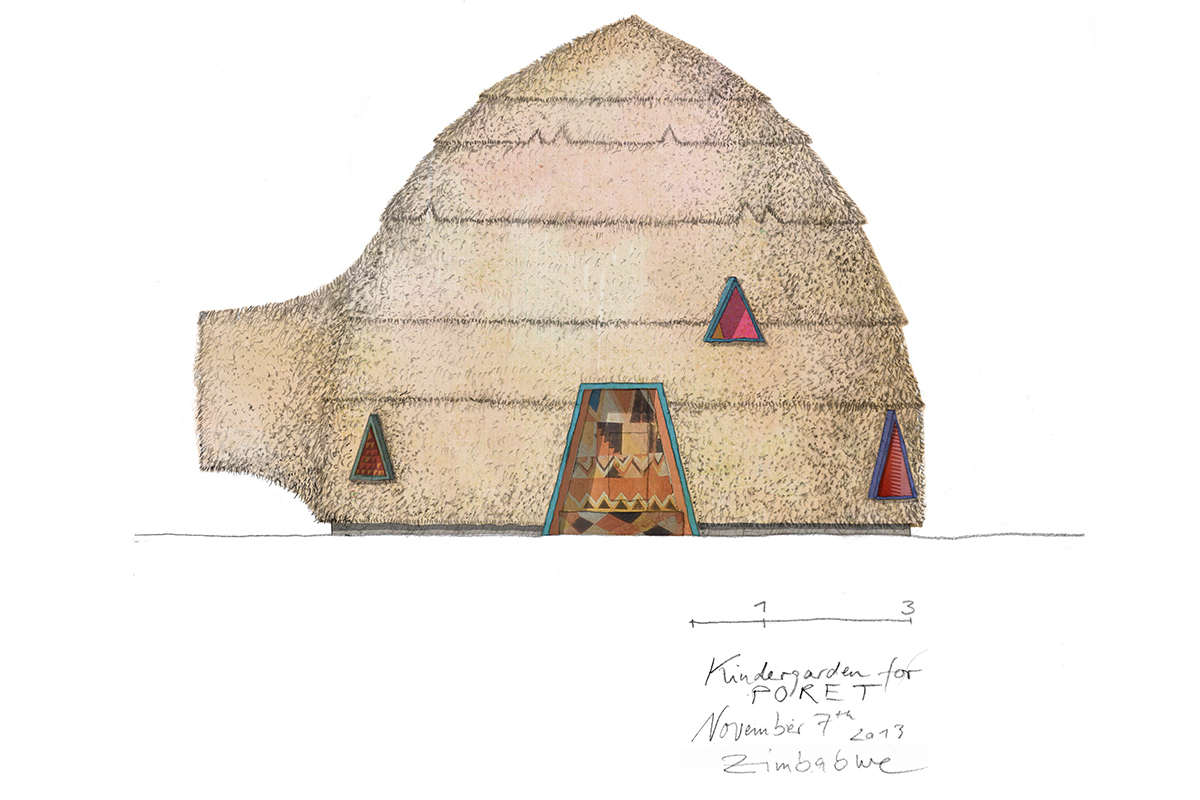

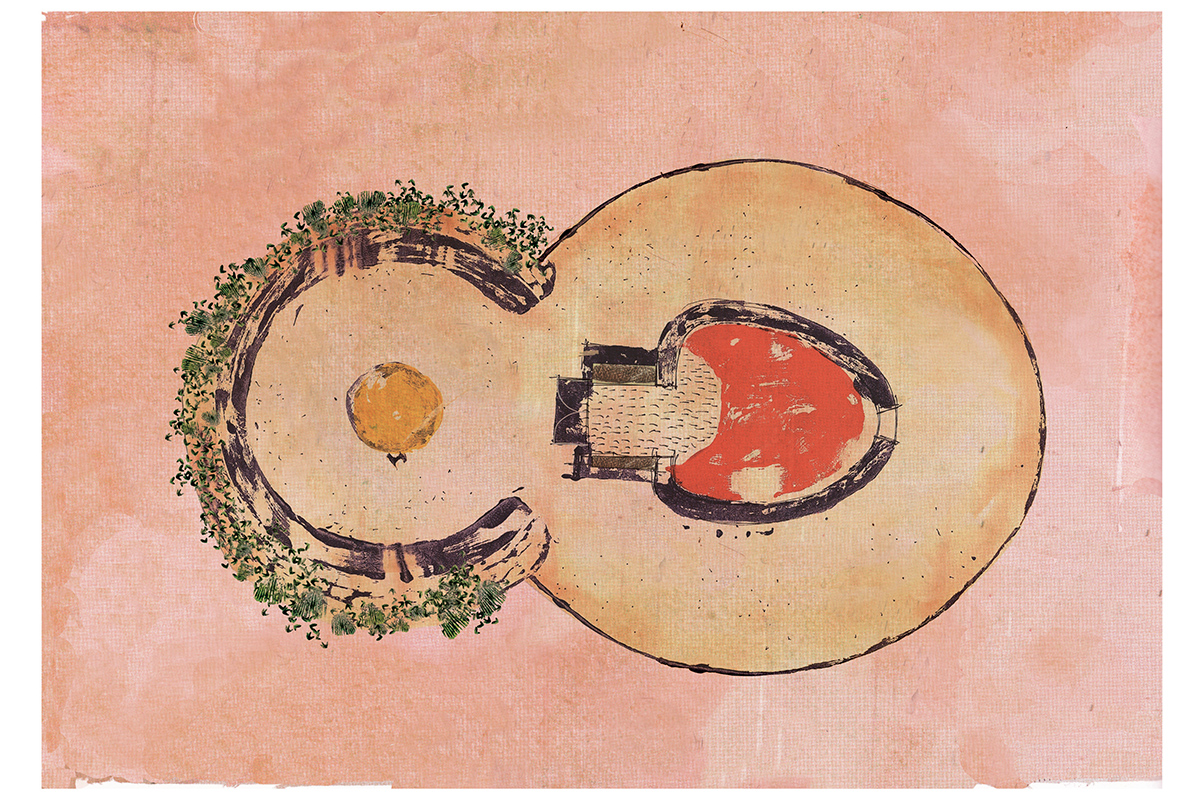

This, however, needs to be changed because mud is the champion for building sustainable, comfortable and healthy spaces. It can perfectly balance the indoor humidity and has immense contribution towards the well-being of one’s mind. It comes along with richness of culture because earth is different everywhere. Wherever you go, it is a different soil which also requires a certain technique and it displays a unique aesthetic. Since the climate everywhere is different as well, using a material from that very region creates an architecture that is one of its kind and absolutely made for that place. The architecture derived is authentic. To me, there is great aesthetic power and beauty in this.

Poret Kindergarden in Zimbabwe by studio Anna Heringer; sketch © Anna Heringer

Poret Kindergarden in Zimbabwe by studio Anna Heringer. Image © Stefano Mori

Poret Kindergarden in Zimbabwe by studio Anna Heringer; image credits: Stefano Mori

Poret Kindergarden in Zimbabwe by studio Anna Heringer. Image © Stefano Mori

Currently, I feel, architecture has become random. With the popularity of concrete and steel, one is building in the same way in an arid climate as they are in a humid climate, creating a design which is out of climatic context. I feel there is real beauty and authenticity lost, through this way of construction.

To convince clients is very difficult. I understand and absolutely agree that one needs and wants a house that they can be proud of, but I don’t think it is a matter of the material. I believe it is a matter of our creativity and architectural design to do it in a way that it looks beautiful. Of course, the people can build with the old material in a very modern way and that is what I am trying to achieve with my designs.

Megha Balooni: Your projects are not only sustainable but the attention to detail paid to materials used exhibits unique properties of vernacular materials. Could you suggest on how one can sensitise this practice more?

Anna Heringer: I think an important thing is to have a good built project published through the media. How often do you see a mud house?

Also, there is a lot of lobbyism going on by the sponsoring companies, because where can one find a company selling mud? There isn’t any advertisement for it. We need more of good projects and good pictures to be present that people read about, to have them watch it in the movies and television to increase its familiarity. We also need it in universities. During one’s education, they learn about bricks and concrete but we don’t have courses promoting the use of modern bamboo.

Bamboo Hostels China by Studio Anna Heringer. Image © Jenny JI

Bamboo Hostels China by Studio Anna Heringer. Image © Jenny JI

Bamboo Hostels China by Studio Anna Heringer. Image © Jenny JI

It has to be as rigorously a part of the curriculum as its other contemporaries. Another thing which can really bring about a change is politics. We need to have carbon tags on materials such as steel, aluminum and concrete. These not only have a lot of carbon dioxide in them but also need immense energy for production. Increasing awareness amongst the consumers would tremendously change things. I believe these are precious materials and one should not necessarily label them as “bad”. The only thing is that they should be used in small doses. When they are too cheap, we overdose and overuse it and that has to be changed on a political level very urgently. It should be the endeavour of every politician to say ‘ok, we’re building a new public building and I want this building’s budget, most of the parts, to remain within this community and not go searching for a cement brand from Mumbai, Shanghai, Zurich or wherever’. I believe these are few changes which would go a long way.

Megha Balooni: What have been the positive outcomes as a result of your association with the UNESCO as the Chair of Earthen Architecture, Building Cultures, and Sustainable Development? Could you talk a little about your role and also highlight few key ideas which you are seeking to push through this collaboration?

Anna Heringer: The program of ‘Earthen Architecture, Building Cultures, and Sustainable Development’ by UNESCO is basically a network. For me, personally, it is a title, though one which is normally given to institutes and universities that provide workshops, training and education in earthen structures. In few cases, it is felicitated to a person. It seeks to disseminate the know-how on how to build with earth. The base station is in Grenoble, France, and those associated with this strongly support each other. Whenever we need expertise, this serves as a good network to reach out and receive the information we need.

Many a times, those pursuing the route of vernacular design might get the feeling of swimming against the stream, and requiring a lot of energy and effort to keep going.

In such times, it is a blessing to know that you are not swimming alone. The institutes, universities and personalities are all working in the same direction and if you hold each other’s hands, then you’re stronger.

MudWorks Harvard, a project of the Loeb Fellowship - concept and design supervision: Anna Heringer and Martin Rauch. Image © Iwan Baan

MudWorks Harvard, a project of the Loeb Fellowship - concept and design supervision: Anna Heringer and Martin Rauch. Image © Ian Lockwood

MudWorks Harvard, a project of the Loeb Fellowship - concept and design supervision: Anna Heringer and Martin Rauch. Image © Ian Lockwood

MudWorks Harvard, a project of the Loeb Fellowship - concept and design supervision: Anna Heringer and Martin Rauch. Image © Ian Lockwood

Megha Balooni: When you say that you are collaborating with institutes through this, is there a possibility to have students intern for your ongoing projects through this?

Anna Heringer: Yes, if we had a project in India and Bangladesh, it would be absolutely possible. In the past we have collaborated with the BRAC university Dhaka and it was a wonderful experience. We had students from Austria and Bangladesh joining for projects and that was wonderful.

Megha Balooni: Sensing the importance and key role that material plays in architectural design, could you suggest and share a few ways which can help the younger architects with better decision making?

Anna Heringer: I think there are many ways. One way is to go for working on actual built projects during one’s architectural education. For a semester, go to a village and work on a community project starting from its design to completion. I think these kinds of projects are immensely helpful in learning, it was the same for me. During my time in Bangladesh, I would see the workers receive money in the evening as their daily wage. Upon heading to the market with them, I saw them spend it to buy vegetables, the women getting a saree and blouse; you can see the money becoming a catalyst for change in local development. Once you see this, buying a bag of cement for foundation feels like a loss in the value of money, one that has no profit for or contribution towards its community. So, once you experience this in a community and design-built projects as a student, then it is very difficult to design in another way.

METI Handmade School, Bangladesh by studio Anna Heringer. Image © Kurt Hoerbst

METI Handmade School, Bangladesh by studio Anna Heringer. Image © Construction Team

METI Handmade School, Bangladesh by studio Anna Heringer. Image © Peter Bauerdick

Another thing I always say is do 1/3rd a job that pays your bills, 1/3rd that fuels your passion and fills your heart and the last 1/3rd to simplify your life - produce some parts of your food that you need, your clothes you wear on yourself and reduce the consumption and shopping.

And with this, you can really manage to do good architecture.

The curriculum is an important aspect of one’s education. I feel you don’t have to build a pure mud house, when you have clients that absolutely don’t wish to, but you could use the normal building techniques to make small changes. For instance, with four columns of reinforced concrete which is usually filled out with fired bricks you could fill it out exactly in the same way with unfired bricks or mud bricks. Lace the interiors of the walls with mud – that will give you a much better interior climate. Or if you have an existing structure, add 2 centimetres of mud plaster and you will start feeling a lot of difference in the interiors. You will realise you do not have to put cement-mortar on it. So, with such things, there are a lot of possibilities and options where one could start.

The more one works with natural materials, the less you start liking the other industrial ones. If you just put your hands in the earth, it feels so good but if you had to do the same thing with cement-mortar, it doesn’t work.

And it is very weird, if one thinks about it carefully, to use building materials where you have to protect your body when you’re working with them. We are living in these materials.

Biennale Venezia by Studio Anna Heringer. Image © Stefano Mori

For me, what is also very important is to keep this question in mind when taking a design decision – how would the planet look like if 7.5 billion people would take the same decision? Do we use this paint? Or do I use this cement-mortar? Or do I use clay? Do I do build with aluminum or with wood or bamboo?

The world is not changing with one big decision but it is changing with every day smaller decisions.

And it might look small, using something like paint but if 7.5 billion would use this paint and it would end up in water, it would completely destroy the planet. And this would make some people very rich while the rest would be completely poor. If everyone starts thinking and retrospecting in this manner, it becomes something really big. Of course, we have to take responsibility and say, yes, I am trying to design and implement beliefs in a way that 7.5 billion people could follow and the work would look good as well. It would be a fair and balanced society with lot of equality. It would be a healthier planet; the cultural diversity would exist and be exhibited in a much better way and traveling to every place would have a new experience to offer. I feel that is also something very important- going to places because they look a certain way.

Omicron living spaces by Studio Anna Heringer. Image © Stefano Mori

Omicron living spaces by Studio Anna Heringer. Image © Stefano Mori

Omicron living spaces by Studio Anna Heringer. Image © Stefano Mori

Megha Balooni: Lastly, could you share a project of your studio where you feel the material used outdid the vision you had for the design.

Anna Heringer: The second project I did – the DESI building. The design was absolutely not done when we started building. I just had a feeling of how it could look like and that was the most wonderful process I had. It was growing with each layer of mud and then when you shape it with your hand, you shape the facades and everything in a different way. In the end it was a total surprise – the spaces, how they were relating to each other and communicating; the proportions were very much rooted in the culture of that place and that was definitely nice.

DESI Training Center by Studio Anna Heringer. Image © Naquib Hossain

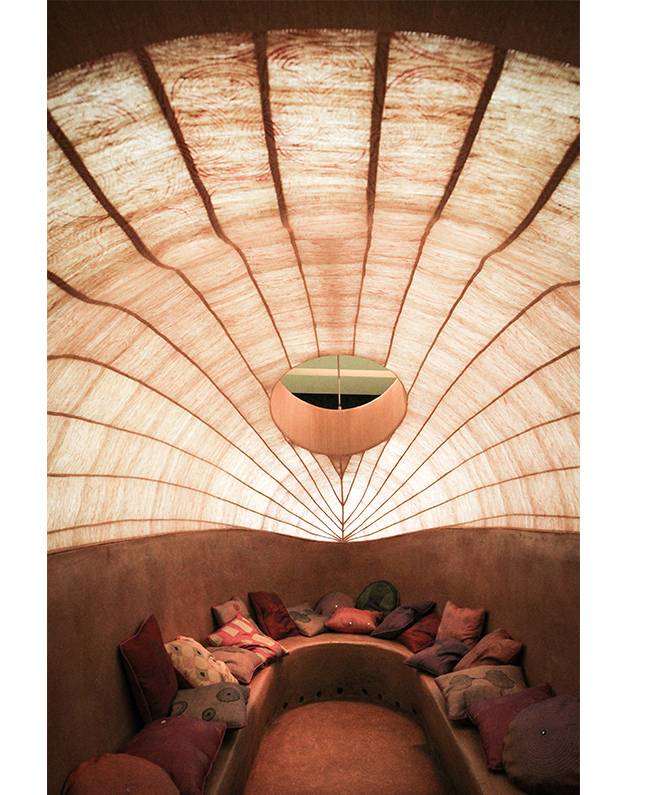

We also just finished a small structure in Austria- it’s a space for giving birth and to experience your senses. For us, it is important to question how one would want their baby to begin the first moment of their life. In a hospital there is all this harsh light, there are antiseptic and easy to clean but awful surfaces. So, we raised a question of whether this is a good start. Wouldn’t it be nicer to start in an earthen womb where one is born with feeling protected while coming to Earth? With this concept, we built a small place in Austria out of clay. I remember before the opening day still working and feeling everything to be perfect but worried only about the acoustics. On the opening day, however, several women were sitting inside and chanting and singing and yodeling and it felt nice because suddenly, even though this was something completely unplanned, the space totally felt justified. The vibration emanating from the singing gave much more relation to the shape and material used which was beautiful.

Sectional plan of the Birth Place. Image courtesy of Studio Anna Heringer

Material process during construction. Image courtesy of Studio Anna Heringer

Material details during construction. Image courtesy of Studio Anna Heringer

The ‘Birthplace’ realized by Anka Dür (Architect & Midwife i.a.), Anna Heringer (Architect), Martin Rauch (Artist), Sabrina Summer, (Designer), Brigitta Soraperra (Cultural worker), Stefania Pitscheider Soraperra (Director of Women's Museum Hittisau). Image courtesy of Anka Dür

For Anna Heringer architecture is a tool to improve lives. As an architect and honorary professor of the UNESCO Chair of Earthen Architecture, Building Cultures, and Sustainable Development she is focusing on the use of natural building materials. She has been actively involved in development cooperation in Bangladesh since 1997. Her diploma work, the METI School in Rudrapur got realized in 2005 and won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2007. Over the years, Studio Anna Heringer has realized further projects in Asia, Africa, and Europe. Anna is lecturing worldwide at conferences, including TED and has been visiting professor at various universities such as Harvard, ETH Zurich and TU Munich.

She received numerous honors: Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, the AR Emerging Architecture Award, the Loeb Fellowship at Harvard’s GSD and a RIBA International Fellowship. Her work was widely published and exhibited in the MoMA New York, the V&A Museum in London and at the Venice Biennale among other places.

Head Image: DESI Training Center by Studio Anna Heringer. Image © Kurt Hoerbst