Submitted by Sarbjit Bahga

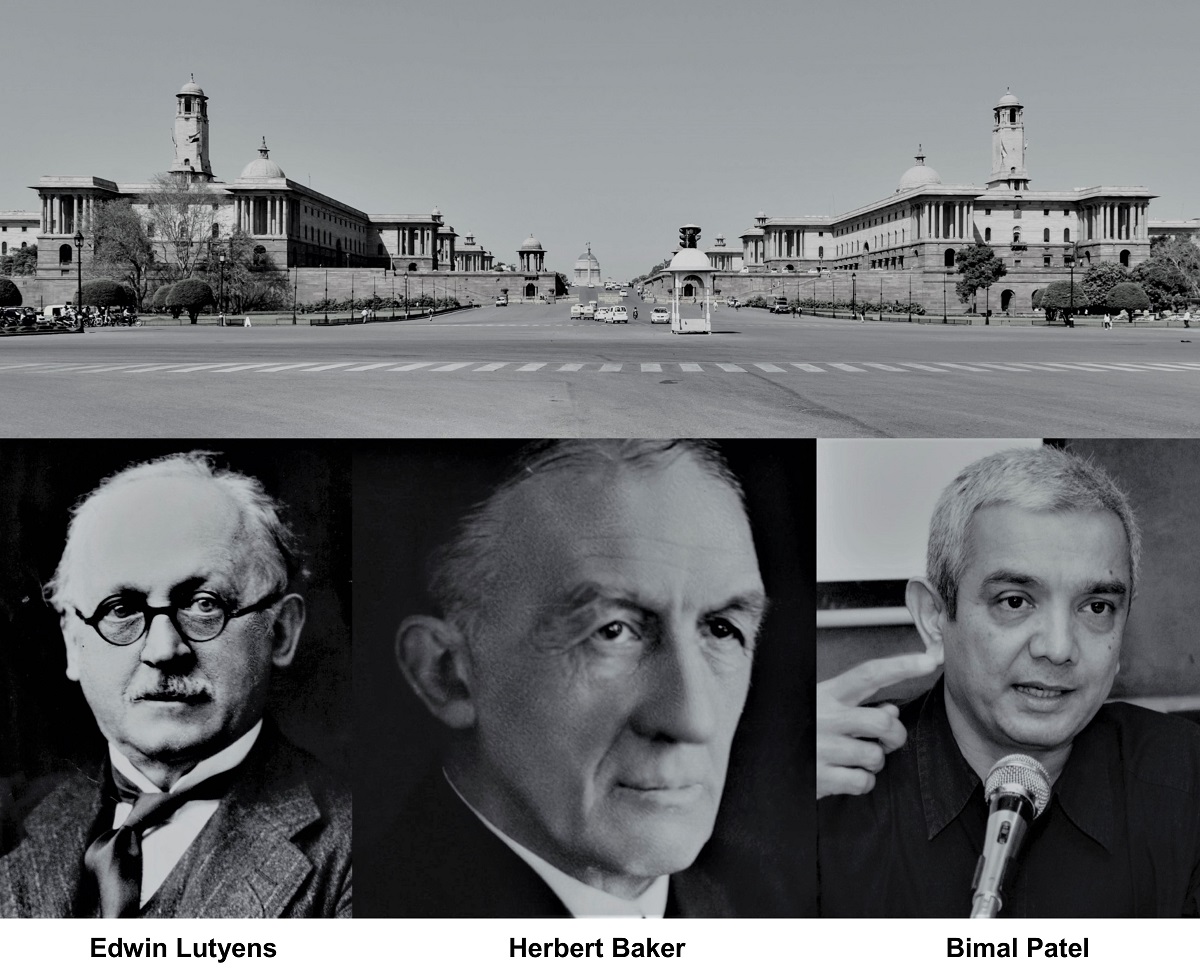

New Delhi Capitol Complex: From Edwin Lutyens & Herbert Baker On To Bimal Patel

India Architecture News - Nov 02, 2019 - 07:43 46177 views

Government of India's decision to revamp the Capitol Complex of New Delhi has become a subject of extended debate throughout India these days. Amid uproar by the architectural fraternity about the procedure adopted by the authorities for the selection of architects, the government moved ahead and selected HCP Design, Planning And Management Pvt Ltd, Ahmedabad headed by Bimal Patel for the project. The selected architects though have a proven record of many success stories yet they have an onerous task ahead due to the historical importance and heritage status of the complex.

New Delhi Capitol Complex: From Edwin Lutyens & Herbert Baker On To Bimal Patel. Photo collage: Sarbjit Bahga.

New Delhi Capitol Complex: From Edwin Lutyens & Herbert Baker On To Bimal Patel. Photo collage: Sarbjit Bahga.

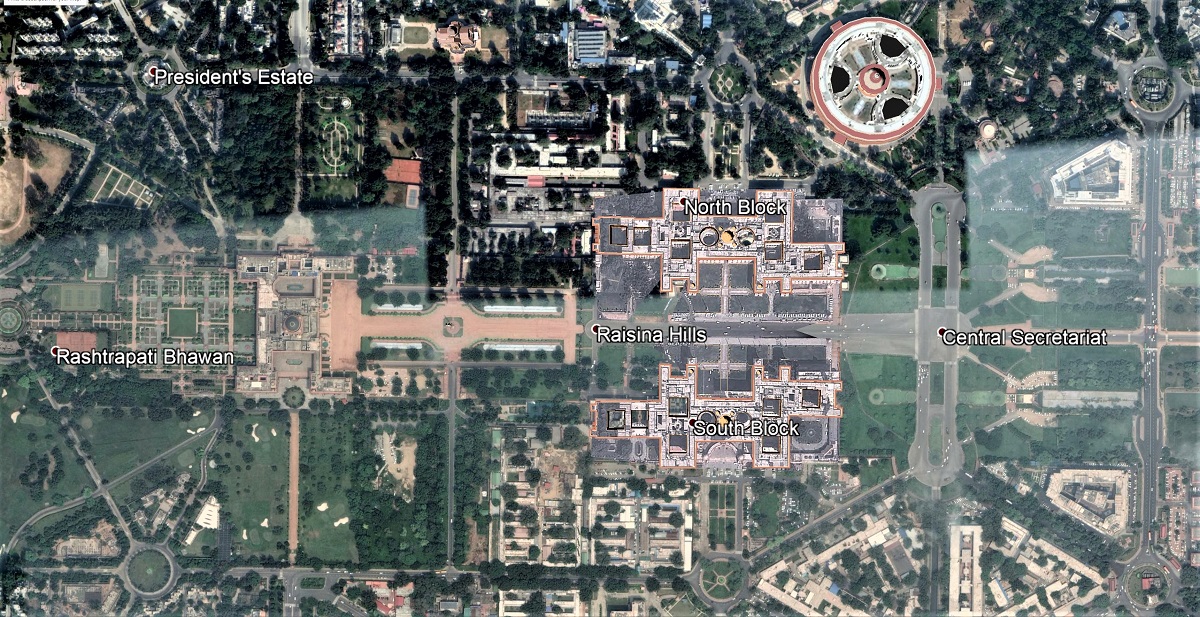

Given the above scenario, it is desirable to through some light on the background of the thought process of British architects and planners who evolved an architecture which they thought was appropriate for The New Delhi Capital at that time. The newly appointed architects will have to keep in mind the design approach of their predecessors as the whole of India will be judging the new design in continuity with the Britishers' school of thought. The Capitol Complex of New Delhi comprising the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Secretariat Building comprising North and South Blocks, Parliament House and Central Vista or Rajpath leading up to India Gate was built in the early 1900s, that is, in the last about five decades of British rule in India.

Panoramic view of Capitol Complex. Photo: A.Savin.

Panoramic view of Capitol Complex. Photo: A.Savin.

North Block. Photo: Bloomberg Quint.

North Block. Photo: Bloomberg Quint.

During this period conscious efforts were made by British architects to take into account the Indian conditions while building. By so doing, they were attempting to send signals through the medium of architecture that, despite being an imperial people, they were organically and inextricably part of the Indian scene. Conscious efforts to express such a synthesis resulted in weird hybrid styles of architecture. A British architect, Sir William Emerson, thought that buildings in India should show distinctively British character and at the same time should adopt the details and essence of native architecture.

The Capitol Complex at New Delhi designed by Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker is an example of a revived imperial architecture breathing an air of Indianness. In their endeavour to make architecture more rational and appropriate to its locale, the British architects had to compromise with elements from the Buddhist, Hindu and Mughal building vocabularies.

North Block. Photo: Laurie Jones.

North Block. Photo: Laurie Jones.

South Block. Photo: Pinterest

South Block. Photo: Pinterest

About the style of architecture to be adopted for New Delhi, Lord Charles Hardinge, the then Viceroy of India, felt that pure Eastern and pure Western architecture would be quite out of place. He emphasized the need to blend both styles. He was confident of the popularity of the new imperial architecture of Delhi. As he put it: "I have no hesitation in saying that I have absolutely the whole of India at my back in wishing that the new city should be built in accordance with Indian sentiments. I do not by this mean that the town should be built of highly ornate or Hindu architecture, but my idea is that it should be a fine broad style with a minimum of decoration, but that decoration should be of the purest and most ancient Hindu ornament. Opinion in this country is quite unanimous on the subject and after all who are we building for - the Indian or the British public?”1

South Block. Photo: Atul Bais.

South Block. Photo: Atul Bais.

Herbert Baker also believed that Indian sentiments could be satisfied by grafting onto classical British architecture certain decorations expressing the myths, symbols and history of the Indian people. Thus spacious colonnades, open verandahs, overhanging eaves or cornices, narrow and high window openings, chhajjas or wide, projecting shade-giving stone cornices, jaalis or pierced stone lattice screens to admit air and not glare and chhatris or free-standing pavilions breaking the long horizontal lines of the flat roof were incorporated into his scheme for two secretariat blocks.

North Block. Photo: Akshay Seth.

North Block. Photo: Akshay Seth.

Herbert Baker, in a letter to The Times of October 3, 1912, explaining his views about the style of architecture to be followed for New Delhi, wrote: "The new capital must be the sculptural monument of the good government and unity which India, for the first time in its history, has enjoyed under British rule. British rule in India is not a mere veneer of government and culture. It is a new civilization in growth, a blend of the best elements of East and West. It is to this great fact that the architecture of Delhi should bear testimony." 2

North Block. Photo: Appaiah.

North Block. Photo: Appaiah.

Edwin Lutyens, being a staunch believer in the principles of classicism, had always advocated Western designs and was strongly opposed to hybrid forms of Indian and European architecture. He believed that European classicism embodied all that was civilized, rational and humanist. His scathing criticism of Indian architecture was: "I do not believe there is any real Indian architecture or any great tradition. There are just spurts by various mushroom dynasties with as much intellect as there is in any other art nouveau… India has never had any real architecture, and if you may not graft the West out here, she never will have any." 3

Lutyens further added: "Architecture, more than any other art, represents the intellectual progress of those that are in authority. In India, they have never had the initial advantage of those intellectual giants the Greeks, who handed the torch to the Romans, they to the great Italians and on to the Frenchmen and to Wren, who made it sane for England…I should have liked to have handed on that torch and made it sane for India, and Indian in its character." 4

Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: Ronakshah.

Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: Ronakshah.

Lutyens' determined efforts, however, ultimately resulted in a complex of exceptional scale and unique picturesqueness, reflecting baroque classicism. His hard principles of Western classicism were to some extent diluted, perhaps due to the sweeping persuasion of Lord Hardinge who declared to Lutyens that "it would be a grave political blunder, and in my opinion, an absurdity, to place a purely western town amidst eastern surroundings." 5

View of Rashtrapati Bhavan from the Mughal Gardens. Photo: Eric Feferberg.

View of Rashtrapati Bhavan from the Mughal Gardens. Photo: Eric Feferberg.

This is evident from Lutyens's design for the Viceroy's Palace (now Rashtrapati Bhavan) in which some elements of traditional Indian architecture are incorporated. The arches, the projecting cornices and the decorative chhatris are reminiscent of both Hindu and Mughal architecture. While the large central dome resembles a Buddhist stupa, the railings remind you of those found at the stupa in Sanchi. Even the adjoining garden west of the palace has been designed on the pattern of the Mughal gardens.

Mughal Garden on the west of Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: Mohsin Javed.

Mughal Garden on the west of Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: Mohsin Javed.

Mughal Garden on the west of Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: India1277.

Mughal Garden on the west of Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: India1277.

Despite their endeavour for indigenization of the European style of architecture by readjusting proportions, adapting layouts, being more responsive to the climate of the country and by the vivid use of shade and shadow with the help of projecting eaves, verandahs, porticos blocked by rattan screens and windows with shutters, the emphasis was on the form, external expression, vistas, axes and symmetry. As such, although this European style of architecture undoubtedly possesses artistic taste akin to Indianness, it is nonetheless soulless.

Parliament House. Photo: Firstpost.

Parliament House. Photo: Firstpost.

Parliament House. Photo: A.Savin.

Parliament House. Photo: A.Savin.

Given the above discourse, the whole of India will be eagerly watching the design approach of architect Bimal Patel and how he will instil Indian soul in the revamped Capitol Complex while maintaining harmony and architectural continuity with the existing one or in utter contrast with it.

Notes:

- Quoted in Suhash Chakravarty, “Architecture and Politics in the Construction of New Delhi,” Architecture+Design, January-February, 1986, p.85, from Hardinge to Crewe, August 29, 1912, Hardinge Papers.

- Ibid, p.91, from The Times, October 3, 1912.

- Quoted in Norma Evenson, The Indian Metropolis: A View Toward the West, p.105.

- Ibid, (Hussey), p.280, and (Evenson), p.105.

- Ibid, (Evenson), p.105.

South Block. Photo: David Castor.

South Block. Photo: David Castor.

Jaipur Column at Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: Christian Haugen.

Jaipur Column at Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: Christian Haugen.

Mughal Garden on the west of Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: Outlook India.

Mughal Garden on the west of Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: Outlook India.

View of Central Vista or Rajpath from Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: Rashid Jorvee.

View of Central Vista or Rajpath from Rashtrapati Bhavan. Photo: Rashid Jorvee.

Aerial View of Capitol Complex. Photo: Google Earth.

Aerial View of Capitol Complex. Photo: Google Earth.

Title image: View of North Block. Photo: A.Savin.