Submitted by Berrin Chatzi Chousein

A matter of Scale

Turkey Architecture News - Jul 04, 2013 - 15:35 8349 views

Joseph Grima takes a drive from Amsterdam to Rotterdam with Rem Koolhaas to talk about domesticity, design and Tools for Life, his first furniture collection, recently presented by Knoll International.

Joseph Grima So you’re living in Amsterdam now, after an absence of several decades from the city where you lived as a child.

Rem Koolhaas Yes. Amsterdam is an incredibly introverted city. I thought it would be difficult to be back here because a considerable part of my life took place in this city—I lived here from 0 to 8 and then again from 12 until 22. From the main bow-window of the house I now live in, I can see the kindergarten where I sat on the lap of Maria Montessori, when she lived in Holland after the war. It’s horribly intimate. Yet this return to Amsterdam was in itself a kind of revelation. Working on an apartment, and a small hut in Italy, gave me more confidence and interest in interiors. Tools for Life is the direct consequence of this.

The OMA team that worked on Tools for Life sitting on the 04 Counter, the symbolic piece in the collection

Joseph Grima What kept you away from design for so long?

Rem Koolhaas It was a form of irritation with consumerism, and a reluctance to do what everybody else was doing: making objects. I became an architect in a time of coffee pots by Aldo Rossi and bed sheets by Michael Graves, and that was kind of off-putting. Then came Memphis, which made it even more alien as a domain. What really helped me overcome my reluctance is a very careful look at the work of Shiro Kuramataand Ettore Sottsass—I saw a number of exhibitions by them and found them suddenly unbelievably impressive and exciting. So in order to embark on this project I had to defeat my own myopia and ignorance.

Armchair and table from the Tools for Life collection, presented at the Prada Foundation to mark the Salone del Mobile. The collection expresses the idea of furniture conceived as equipment for living, therefore requiring high levels of performance

Joseph Grima Were the Metabolists an influence? A few years ago I remember sitting in on a fascinating interview you did with the Japanese designer Kenji Ekuan, who was originally a member of the Metabolist movement.

Rem Koolhaas We interviewed many designers for the Project Japan book, and my revived interest in design is also a result of that research—it was totally eye-opening how urgent design could seem. And then I met the people who had worked for Kuramata and saw the amazing things they were still doing, so you could say that Tools for Life is also the product of a renewed interest in and exposure to Japan.

Joseph Grima Performance, movement and transformation seem to be recurring themes, almost obsessions, in your work—from Maison à Bordeaux to Prada Transformer and from the Serpentine Pavilion to this project.

Rem Koolhaas It’s true, but of course you never think of it as an obsession, more as a necessity. I don’t know whether you saw that show at the Barbican, “OMA/Progress”, where we were “edited” by Rotor. They arranged a special room on the theme of movement. Until then we’d never really thought about it. It’s probably good not to be too aware of these so-called “themes” because there’s a risk they can end up manipulating you.

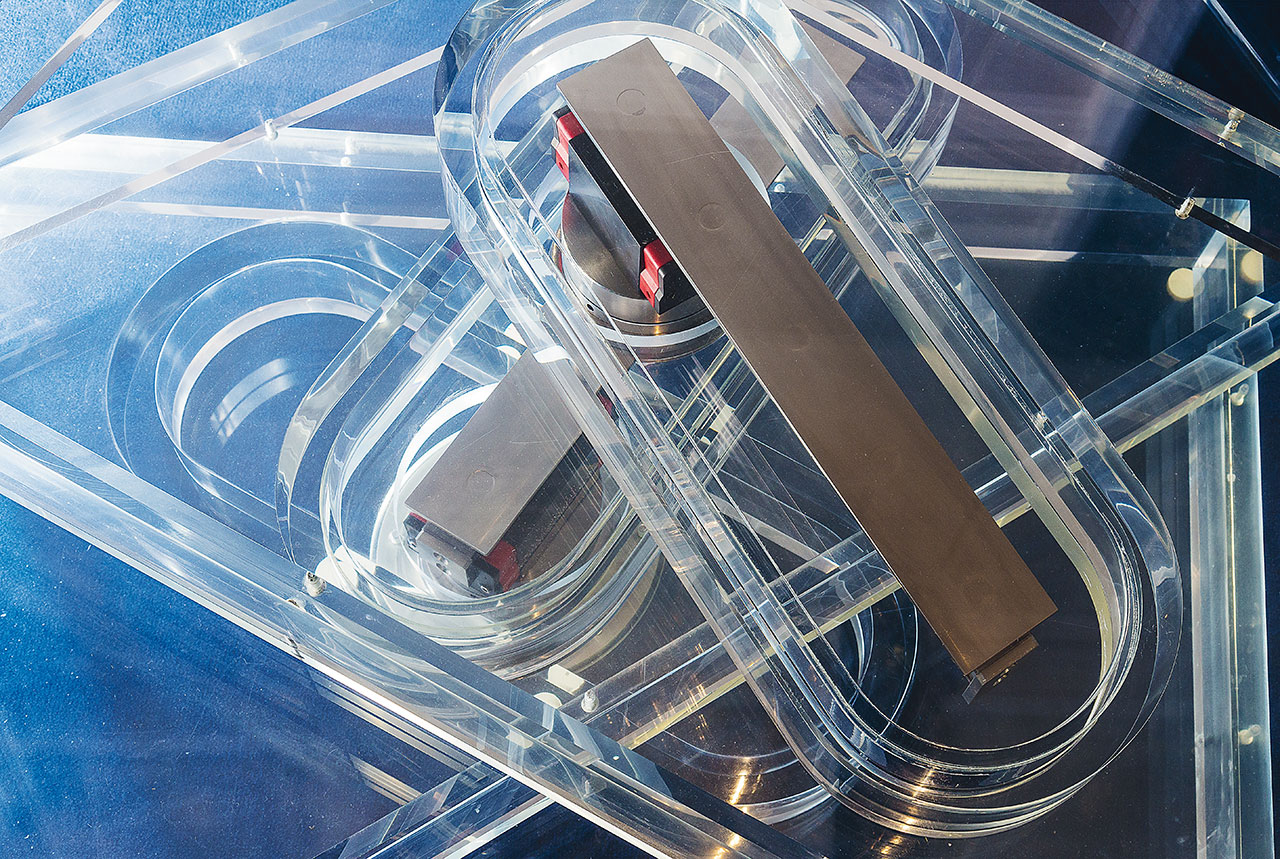

The 03 Coffee Table is made up of a stack of three transparent acrylic parallelepipeds. Internal slides allow the individual elements to be rotated and extended outwards, making it possible to adjust the design’s complex shape to suit one’s needs

Joseph Grima Still, you seem to enjoy embedding heavy machinery in the domestic sphere, and embracing certain aesthetic qualities of the industrial.

Rem Koolhaas It is true... Maybe it’s a polemic about the mechanical, because the mechanical is now given so little consideration with respect to the digital. You see how Germany thrives because it’s still tied to the mechanical. We were also very lucky to become acquainted with a company called Goppion in Italy that does very ambitious engineering for display systems of museums like the Louvre. Through them, we discovered something unexpected—that engineering on the micro scale of furniture can be as interesting as engineering on a big scale.

The 01 Arm Chair is a revolving lounge seat that can be adjusted in height by pressing a button on the column-shaped mechanical base. It has an external structure in transparent acrylic and leather internal upholstery. The supporting base plate is in concrete

Joseph Grima What made you go for the extreme high end as opposed to the democratic, accessible end of the furniture spectrum?

Rem Koolhaas Mainly the fact that that kind of design has been done well in the past and is being done so well now. That category of furniture has reached a very high level. There are a lot of amazing designers out there. But very little of it serves multiple purposes.

Joseph Grima This is your first real engagement with industrial product design. Did it affect your ideas about interiors? Until now you’ve always counted on very close collaborations with designers such as Maarten Van Severen or Petra Blaisse.

Rem Koolhaas We continue to collaborate, but the Knoll project felt different, like discovering new territories in an overcrowded field.

The 04 Counter is a monolithic composition of three blocks; thanks to a mechanical system, the two upper bars can be rotated to become shelves or seating

Joseph Grima If the right client were to come along, would you consider working on the domestic scale again? Would you like to design a house?

Rem Koolhaas Of course. I want to design houses, but finding the right client is a real problem. It’s a matter of scale—the typical client who wants a house today wants a house of 2,000 square metres. That is the scale of a palace, I don’t know if I can do that scale.

This interview was published on Domus 970 / June 2013

via Domus