Submitted by Antonello Magliozzi

John Boon on "adding a new chapter to the book of a place"

Italy Architecture News - Nov 16, 2023 - 13:10 2746 views

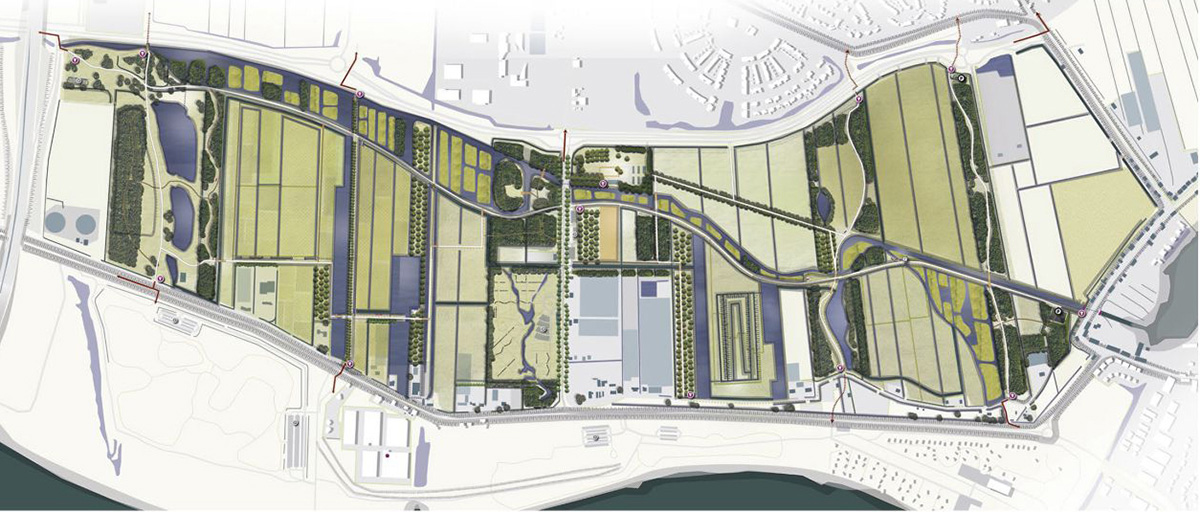

"I like to say: landscape is a book, and we only add a chapter, we don't rewrite the whole book." This is how John Boon introduces his working philosophy as a landscape architect in an exclusive interview to the World Architecture Community. This is a vision that stems from his background in both science and the humanities, which has earned him several international awards, such as, for example, the one he won last July 7 at the Milan Triennale in the CityScape awards 2023, with the Zuidpolder Landscape Park in the Rotterdam Region. A project that summarizes the importance of functional solutions "so as to make environments attractive to the people who live in them, who can also recognize these within a traditional landscape." And in this regard, John states that he “did not try to make tabula rasa, but to reuse what already exists." Indeed, he says: "we approached the existing landscape as if it were a book that just needed a new chapter."

Zuidpolder Barendrecht. Image © Arcadis

John is a Dutch landscape architect with an international background that comes from experience in various projects in Belgium, Turkey, South Korea, Dubai, China, Peru, France, and recently Colombia. Since 2005 he works at Arcadis with the role of landscape architecture and urban design team leader in The Netherlands. In addition, John is a member of the Executive Committee of the International Federation of Landscape Architects in Europe. As per flagship projects, he had also a role as chief designer of the World Horticultural Expo Floriade 2012 in Venlo. In all his projects he has integrated multiple functions in a clear and strong concept to address climate change related issues, and then “to provide sustainability solutions for mitigating and solving problems related to build and natural environments.” Therefore, his focus has been the most on making places healthy and resilient.

Floriade 2012 Venlo. Image © Arcadis

Speaking about his different projects, John narrates that he normally deals a lot with “how to conserve water, how to reduce heat stress, how to provide "greener" spaces for people”, because he believes “these aspects are aimed at providing good solutions for people's health. He recognizes this approach within his company genes since projects are assumed to be life cycles processes including long-lasting timeframes together with well-balanced solutions. In this regard John says: “it is very important to always think "big to small," so start from the highest level of the system-project.” “For example, if we are dealing with pipes to be placed in the ground of a project, we need to follow a specific workflow. First, we need to ask whether our project really needs pipes and answer the question: is it possible to keep the water there, where it is now? Once we have clarified the objective need for drainage pipes and when we go to the level of detail, we then need to find the best solution in terms of sustainability”.

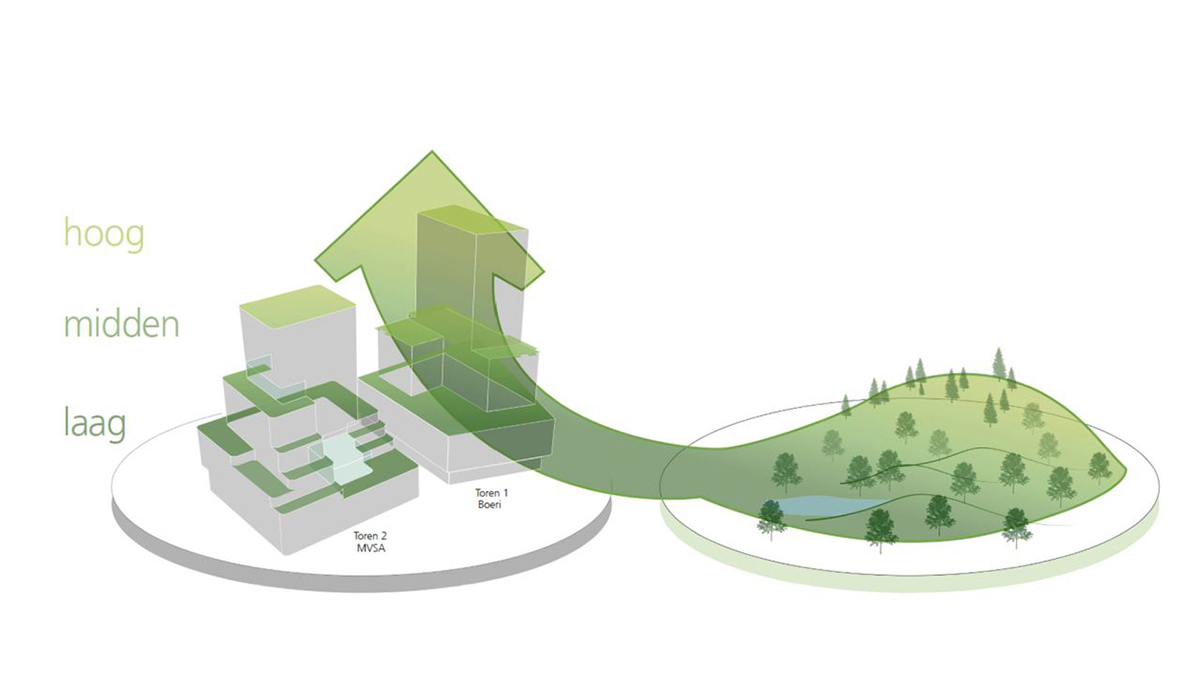

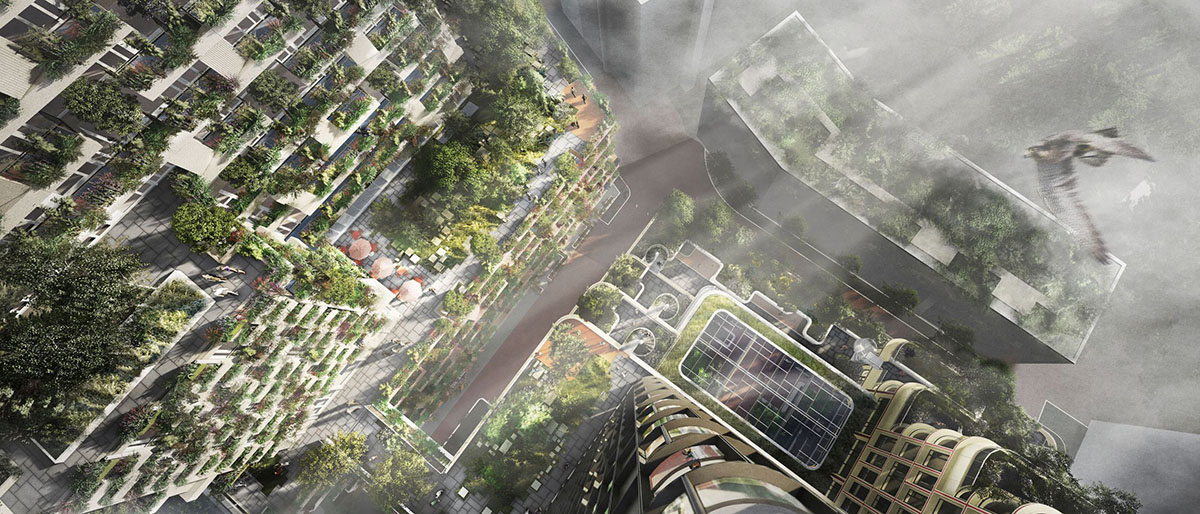

Wonderwoods towers Utrecht with Boeri architects and MVSA architects. Image © Arcadis

In his role as a landscape architect, John explains that in the Netherlands it is important to be educated to be both artist and engineer. This is because the landscape requires science-based solutions and attractive outcomes for people and nature. However, what makes landscape a cultural element is the interconnection between natural areas and the built environment, and thus with architecture. Indeed, “this is because landscape unifies all things”, but with a focus on the exterior-interior relationships. To explain this concept John recalls the Wonderwoods Vertical Forest project in Utrecht, where he contributed as landscape architect, collaborating with the Stefano Boeri Architects team. In this case, “the architect thought about the design considering the perception of the building from the inside-out, reflecting what people could see from the living”. On the other hand, John's idea was instead “to think about what people could see from the outside”, focusing primarily on “the interconnection between the building and its surroundings.”

Esenler Park Turkey. Image © Arcadis

John thinks that today the collaboration with communities is becoming more and more important. “Before, the architect was a person who thought about the project from a top-down perspective. But now that is no longer the case. The communities have a voice in the projects we do, and that is why we think it is important to involve them very early in the design process”. According to this approach, it becomes important to let the people themselves set the goals, so that they drive the main choices of the project. This is why John says that in his projects he defines different scenarios, trying “to give space to the nature as people want, including, for instance, agricultural solutions to meet the needs of farmers or specific stakeholders.” At the same time, he considers different speeds of development according to the set objectives. He tries to construct a framework of landscape elements (like forrest or hedgerows) that needs time to develop slowly and without disruption. Within this strong landscape framework more dynamic functions (like agriculture) can find a place.

Zuidpolder Barendrecht. Image © Arcadis

Our history is a top subject for John, since he states that “It is always important to know where we come from”, and then to consider that “landscapes are part of the identity of communities.” “However, because the landscape has always changed throughout history” he also thinks that “we should not only have a "protective" function towards our landscape heritage.” “It is a strange idea to freeze the landscape in the way we see it today!” “People get lost if they can’t ‘read’ the landscape anymore because everything changes so fast; there is a strong connection between landscape and memory”. This is why, even though John loves our historical landscape, he thinks this cannot be considered as a kind of museum. “Our historic landscapes have to accept a certain progression of development” to remain alive, “to allow people to work, like allowing farmers to produce in a modern way.” “Many people have great resistance to change, but on the other hand, standing still means going backwards” John believes we should combine historical heritage with new technologies in an intelligent way. Thus, “innovations such as artificial intelligence or those that allow us to get good information about how the landscape works, why it works the way it is, and how it could work in a better way, can actually help us write new chapters in the book of our landscapes.”

Zuidpolder Barendrecht. Image © Arcadis

Read the full transcript of our interview with John Boon below:

Antonello Magliozzi: John, could you introduce yourself and tell us what is your personal definition and approach to landscape design?

John Boon: I am a Dutch landscape architect with an international background that comes from experience in various projects in Europe, South America and Asia. I have worked at Arcadis since 2005 in the role of landscape architecture and urban design team leader in the Netherlands, and I am also a member of the Executive Committee of the International Federation of Landscape Architects in Europe.

To answer your question, I would start by saying that I think landscape unifies all things. Together with my team, I work a lot with architects and urban planners, although we focus more on outdoor spaces. In this context, we aim to address climate change issues so that we can provide sustainability solutions for mitigating and solving problems related to build and natural environments. We deal a lot with how to conserve water, how to reduce heat stress, how to provide "greener" spaces for people, because we know that these aspects of the projects are aimed at providing good solutions for people's health. I could say that it is an approach that we have in our genes, and in that we see projects as processes. This I think is the big difference between an architect and a landscape architect. An architect creates an object and then the maintenance is there to stop the decline. In our case we start building and planting things, but maintenance is there to make them grow and become the image we had in mind. So, we have to think by processes, and that is very important, I think.

Zuidpolder Barendrecht. Image © Arcadis

Antonello Magliozzi: Can you give some examples of your top projects to explain your working method?

John Boon: One of my flagship projects was the World Horticultural Expo Floriade 2012 in Venlo, the Netherlands. It was a big event visited by about 2 million people. And yes, for me it was really something very special, because as a landscape architect I suddenly got a lot of space to put into practice everything I always wanted. But there are several other projects in the "side folder," for example I can mention the project recently rewarded at the CityScape Award 2023 at the Milan Triennale: the Zuidpolder Landscape Park, a contemporary landscape park with (clean) water storage in the Rotterdam Region. I think this is a really good example of how these environmental solutions can lead to a very interesting new landscape. In this case we did not in fact make a water storage according to specific needs, but a new landscape that was attractive both for nature and also for people to be recreational. In other words, we always try to do functional things in a way that makes the environments attractive to the people who experience it, who can also recognize it within a traditional landscape. And yes, I can then say that in this competition, as usual, we tried not to make a " tabula rasa," but to reuse what already exists. I like to say: landscape is a book, and we only add a chapter, we don't rewrite the whole book. We dealt with the existing landscape as if it were a book that just needed a new chapter."

Antonello Magliozzi: It is indeed a beautiful metaphor for a landscape project! At this point I ask you: if you had to choose the biggest challenge for a landscape architect, what would be your answer?

John Boon: I think our biggest task is to really think about what the planet requires from us. I think so because landscape architects use a lot of hard materials that use carbon dioxide. Sometimes we like to use hard materials because they look very fancy, but I think we have to solve some serious problems above all. That's why our main task is to be a bit stricter in minimizing hard materials, putting more "green," taking care of water. We cannot look the other way anymore!

Wonderwoods towers Utrecht with Boeri architects and MVSA architects. Image © Arcadis

Antonello Magliozzi: John, how do you relate to architecture or, in other words, how does architecture interconnect with the landscape in your projects?

John Boon: In the Netherlands we are very educated to be both artists and engineers. That means we have to be engineers and make things that work and go well, while, on the other hand, as artists, we also have to make something attractive to both people and nature. Therefore, when I am asked to make a natural area, I always see it as a cultural thing, which means that the natural area is always interconnected with the built environment, and therefore with architecture.

Longgang River Park Shenzhen. Image © Arcadis | CRTKL

Antonello Magliozzi: How does your landscape design relate to the climate change issues? How you measure environmental performances that are addressed to solve climate related problems?

John Boon: I believe it is very important to always think "big to small," so start from the highest level of the system-project. For example, if we are dealing with pipes to be placed in the ground of a project, we need to follow a specific workflow. First, we need to ask whether our project really needs pipes and answer the question: is it possible to keep the water there, where it is now? Once we have clarified the objective need for drainage pipes and when we go to the level of detail, we then need to find the best solution in terms of sustainability, adopting, for example, the best materials in terms of CO2 emissions. And that is what measures the sustainability of the project! Our first goal is to use as few materials as possible, and if materials are really necessary, we must use the best from the point of view of environmental performance. Sometimes it is not very easy to measure such performance, although I can say that this work is increasingly facilitated by innovative digital tools. For example, if we need to solve issues related to heat stress, we can now in fact build models that indicate whether our design improves the heat stress of a location. The same is true for water-related problems. We create models that can see the current situation and, at the same time, how the project can improve performance with two or three scenarios. So I think digital tools will help us more and more to achieve evidence-based design.

Antonello Magliozzi: When doing a landscape design, are you also measuring performances related to the social outcomes in term of direct and indirect benefit for the community?

John Boon: Yes, I think collaboration with communities is becoming more and more important. Before, the architect was a person who thought about the project from a top-down perspective, that is, without having specific relationships with communities. But now that is no longer the case. The communities have a voice in the projects we do, and that is why we try to involve them very early in the design process, and then have them participate in all phases of the design itself, up to the measurement of the project results. According to this approach, it becomes so important to let the people themselves set the goals, so that they drive the main choices of the project. So, very often we discuss with people in the community about various topics, such as: how we want to live together in an area or how we want to hand it over to our children. And that always leads to very interesting discussions, although sometimes there are of course oppositions, as for example happened for a project with farmers, who had different ideas about how to handle the nature of a project. However, when you ask the various representative of the community how they intend to hand over an area to their children, the whole community often finds agreement on the design solution. Therefore, in our projects we define different scenarios, where we try to give space to the nature as people want, including, for instance, agricultural solutions to meet the needs of farmers or specific stakeholders.

Wonderwoods towers Utrecht with Boeri architects and MVSA architects. Image © Arcadis

Antonello Magliozzi: How a landscaper deal with projects that are related to spaces within the cities? May you make an example?

John Boon: I think we try to work at the same level as the architect who designs the buildings. We try to collaborate with other specialists because we think all disciplines can add something to the others. While the architect focuses more on the interior-exterior relationship, we landscape designers are more focused on the exterior-interior. If you can combine these approaches, you can really get a better design result! For example, when we participated in the Wonderwoods Vertical Forest project with Stefano Boeri in Utrecht, he of course thought about the design considering the perception of the building from the inside out, considering what people could see from the living. Our idea, on the other hand, was to think about what people could see from the outside, and how those people who don't live in the building could profit from it. So our thinking focused primarily on the interconnection between the building and its surroundings. In this example of the Wonderwoods project, we had a very interesting discussion with Stefano Boeri's team, in which we explained the importance of the local landscape, so we could connect the project to the national landscape near Utrecht. A criterion that, according to our idea, would have allowed the vertical forest to become part of the local landscape, and that was very much appreciated by the architect during the design.

Wonderwoods towers Utrecht with Boeri architects and MVSA architects. Image © Arcadis

Antonello Magliozzi: I think this is an excellent example of symbiosis between landscape and architecture! On the other hand, in the case of a landscape project in the countryside that requires restoration, and where the project itself does not have specific boundaries, how are ecosystem units considered and how do you intervene in the design?

John Boon: In the Netherlands we very often work with a framework called Casco. This framework includes multiple landscape structures for the various ecosystems, those that develop very slowly over time, such as forests, and those that are susceptible to easy and quick changes, as in the case of agricultural land. To give an example, inside Casco, we could have a forest landscape that also includes agricultural land. With this approach we consider landscape design with different speeds of development according to the set objectives. To answer this question, in territorial landscape projects we consider the overall structure, while working on different characteristics and specific interventions within sub-structures, in order to preserve lasting results for the entire ecosystem unit through different speeds of transformation.

Leidse Ommelanden, Arcadis with Dijk Stad & Land. Image © Arcadis

Antonello Magliozzi: Now a controversial question that I usually do: what is your recipe for the future? Does in the future will be more important to consider the lesson learned from the history or that of the recent innovation and technology, such as that of the artificial intelligence? Or a combination of these?

John Boon: I think it will be a combination. It is always important to know where we come from. To me, our history is very important because it is part of our identity and, consequently, landscape is part of the identity of communities. However, because the landscape has always changed throughout history, I also think that we should not only have a "protective" function towards our landscape heritage. So, I would say it is a very strange idea to freeze the landscape in the way we see it today. Of course, we love our historic landscape, but we cannot see it as a kind of museum landscape. I think our historic landscapes have to accept a certain progression of development. The things you mentioned, such as artificial intelligence and other such innovations, can actually help us write new chapters in the book. But yes, neither the idea of preservation nor the idea of innovation prevails. I believe we should combine historical heritage with new technologies in an intelligent way. When I am in Tuscany, I think the landscape is so beautiful that I should never make a plan to wipe it out, but on the other hand I should never put a fence around Tuscany and ask people to pay to enter. That place needs to be alive, to allow people to work, like allowing farmers to produce in a modern way. It is a question of the right balance between ancient and modern. This is our more important goal.

Antonello Magliozzi: My very last questions. When you speak about digital solution applied to landscape, are you also including landscape information modeling where could also generate a kind of digital twin for the better monitoring of landscapes?

John Boon: That is exactly what we are looking at! GIS systems, for example, allow us to get good information about how the landscape works, why it works the way it is, and how it can work in the future with a project. That's a possibility that we are starting to exploit more and more today, and that didn't exist 20 years ago. In fact, especially now we are concerned with including such technologies in all our projects, having realized that these are facilitating a new methodology of work. I believe the new chapter of our book has already begun!

Arcadis, Landscape Architecture & Urbanism team© Arcadis

Top portrait image in the article: John Boon courtesy of Arcadis.

All images courtesy of Arcadis unless otherwise stated.