Submitted by Tarun Bhasin

Day 3 Summary on Z-Axis 2018 Conference in India

India Architecture News - Sep 10, 2018 - 15:41 17412 views

The 2018 Z-Axis Conference was organized by the Charles Correa Foundation at Kala Academy, Panaji, Goa in India from 6-8 September. Titled "Designing Equitable Cities", the conference aimed to talk about the discourses of architecture and planning as agencies involved in the design of resilient and equitable cities through individual presentations and panel discussions.

The first day of Z-Axis focused on screening movies on/by Charles Correa to begin to sensitize the audience on issues of rehabilitation, participatory approach, and scale of neighborhood planning; on the life and works of Charles Correa; and the trends of urbanism through the history and development of Mumbai. It was followed by ‘Living Ideals’ exhibition at the CCF office in Fontainhas, Goa, curated by Ar. Rohan Varma and Prof. Dirk van Gameren. Later, the opening note by Nondita Correa Mehrotra encapsulated questions that provided the premise of the entire conference and idea behind its theme.

While the opening lecture by former Justice Gautam Patel was a re-telling of the story of Charles Correa’s waned efforts for the redevelopment of Mumbai Mills Complexes and the spatial injustice that prevails in Indian cities; the Memorial lecture delivered by Prof. Richard Burdett defined the scope of deliberations for the entire conference with a comprehensive presentation spanning urban growth trends, future of architecture and urban development, possible approaches to the notions of equity and their meaning in different geographies (primarily the Global South), the question of political will, desires of public regarding social, economic and environmental growth, and physical interventions to enhance the capacity of the city to deliver to its citizens, by citing examples from his book titled ‘Shaping Cities’, and from his work for the London Olympics.

The second day carried forward the nuances from the theme and scope defined on the previous day. Ar. Rahul Mehrotra talked about the need to combine architecture and social sciences, witnessing patterns from the planetary scale to the scale of a building, and through his own works, he showed how physical intervention could result in positive social transgressions. Ar. Sanjay Prakash lectured on countering urban sprawl, debunking the fads related to sustainability and providing tactics for maintaining physical stocks and flows at an individual and public level, both. Ar. Mohan Rao revealed the role of autonomy of nature in maintaining equity, citing religious and cultural examples that portrayed nature as a part of spatial language having an interpersonal identity within the society; he talked about natural exclusion in modern times as the culprit behind the collapse of livelihoods and community values.

Ar. Alejandro Echeverri revealed the idea of Socialist Urbanism citing examples from his Urban Integral Projects in Medellin that addressed the socio-political situation of the city through urban acupuncture. The day voiced arguments from contingent on human rights represented by Shivani Chaudhary fighting against inequality, homelessness and forced eviction; Geetam Tiwari in favour of creating accountability in road planning towards pedestrians, cyclists and neighbourhood mobility; and Jagan Shah with a thought-experiment shunning tautological talks on ideology, and bridging the gap between decision-making and data systems to enhance accountability. The day ended with a keynote lecture by Prof. Joan Busquets talking about images of transition between various stages of a city, citing examples from the history of urban development of Barcelona and planning for Barcelona Olympics, encompassing examples to express the need for more bottom-up entrepreneurial approaches in planning required due to the irrational morphological behaviour of modern cities.

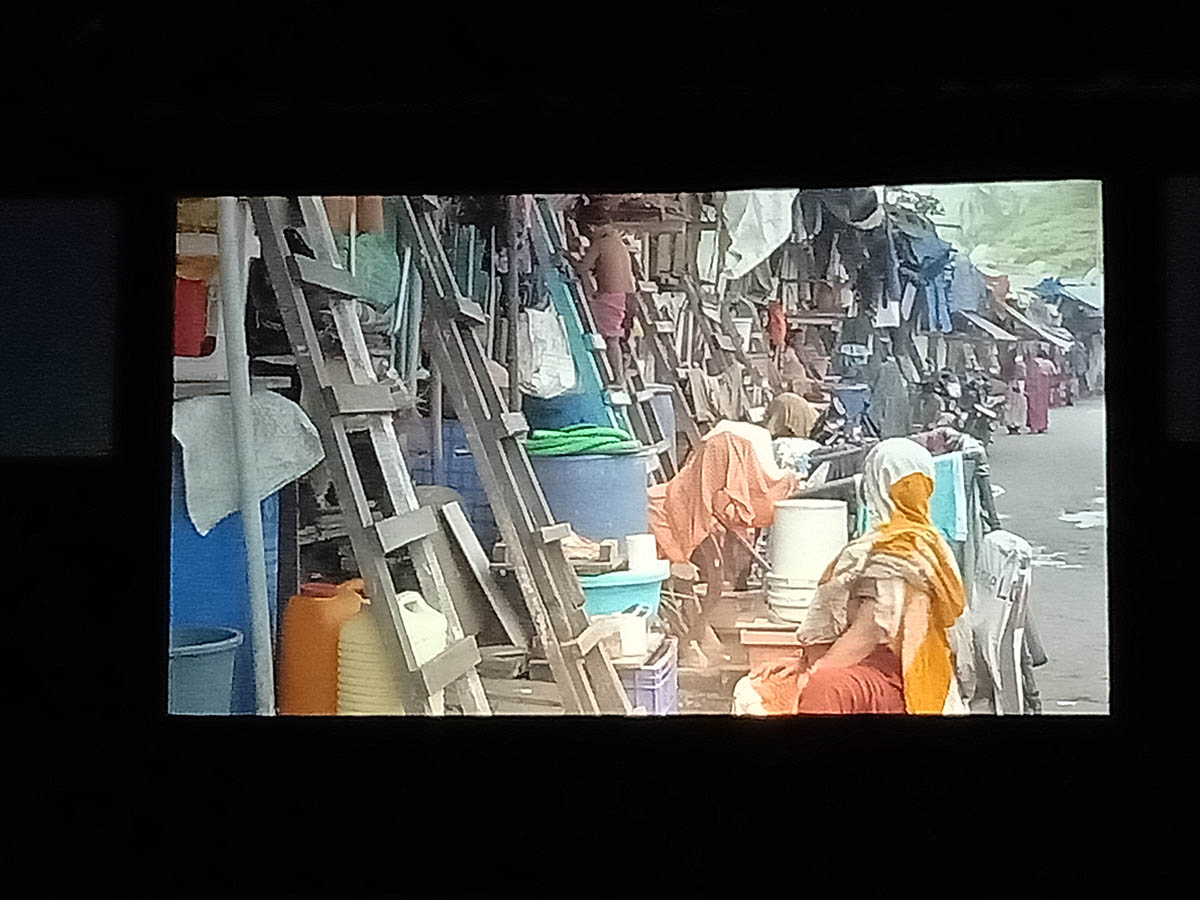

The third day of Z-Axis 2018 started with a section dedicated to issues of housing. Strengthening focus on the ‘Living Ideals’ exhibition, the day started with the screening of the documentary ‘State of Housing’ by Rajiv Shah. The documentary talked about the commoditization of spaces, especially housing, in Indian cities, towns and even villages, in lieu of speculative measures by the market forces to generate profits; versus the needs and aspirations of the public. Citing examples from various cities, it showcased struggles of individuals and communities, bringing in issues of gender, education, and healthcare.

It voiced opinions from experts, and the destitute, in a heart-warming narrative that broke down the issues related to the housing problem in India-from the absence of constitutional provision to guarantee ‘Right to Shelter’ as a fundamental human right, to the lopsided policies and planning of metropolitan areas. The documentary was not just factual but incorporated into its narrative, more sensitive meanings related to the idea of homes, and propositioned to replace the hollow ideas of the word ‘housing’ with more sensitive ideals of the word ‘dwelling’ as a measure to change public perception, ending with a statement of expression - 'We can call a dwelling our home, or a community, or a time, or a place, or the country; but a home must feel like a home.'

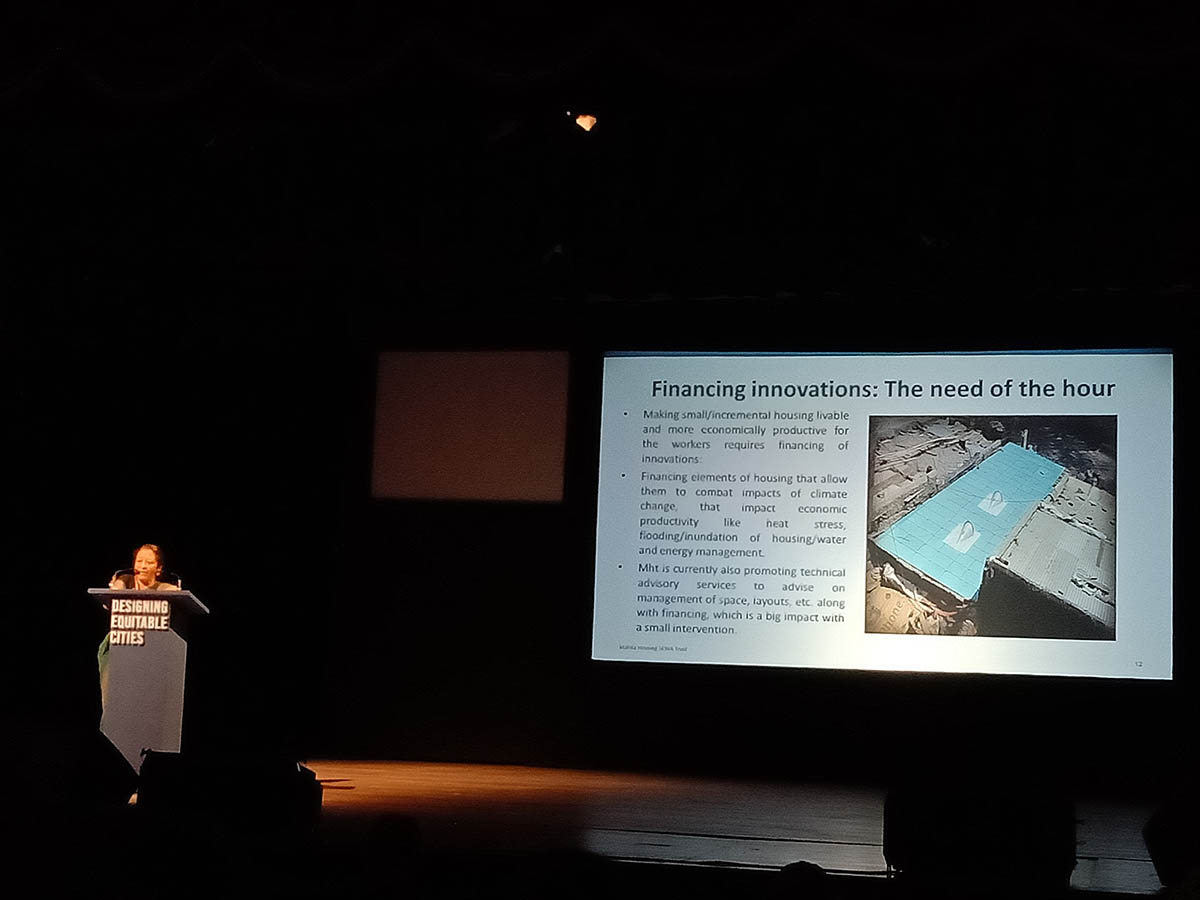

The documentary defined the context on the issue of housing and was followed by a presentation from Brijal Brahmbhatt who began by talking about her role in gender-sensitive reform schemes for that sought to uplift access of women in underdeveloped areas, to services and economic opportunities. She, then, talked about the ‘Parivartan’ Programme in Ahmedabad that focused on provisioning and upgrading slums by working on public infrastructure such as water supply, sewerage, stormwater drainage, individual toilets, paving of internal roads, street lighting, landscaping, community upliftment programs and delinking of tenure.

“Since a majority of the houses in India are built by the people on their own, innovation in housing finance is one of the most crucial interventions in realizing affordable housing,” she stated and steered the conversation to her efforts to improve the situation of housing finance and ownership rights. She shed light on the concept of providing ‘progressive tenure’ for monitored growth and incremental development of the informal sector. Her talk included examples of physical interventions that addressed issues of fire-safety, adherence to local bye-laws, and sustainability through small-scale affordable interventions that could easily proliferate from one dwelling to another.

Lastly, she showcased how building regulations of the past were driving up the threshold cost of a permanent dwelling, and detailed her efforts to tinker housing regulations in Ahmedabad, to shed the basic cost of a dwelling by up to 30%. Her presentation addressed housing interventions at all scales – gender, planning, policy, affordability, finance, bye-laws, and regulations.

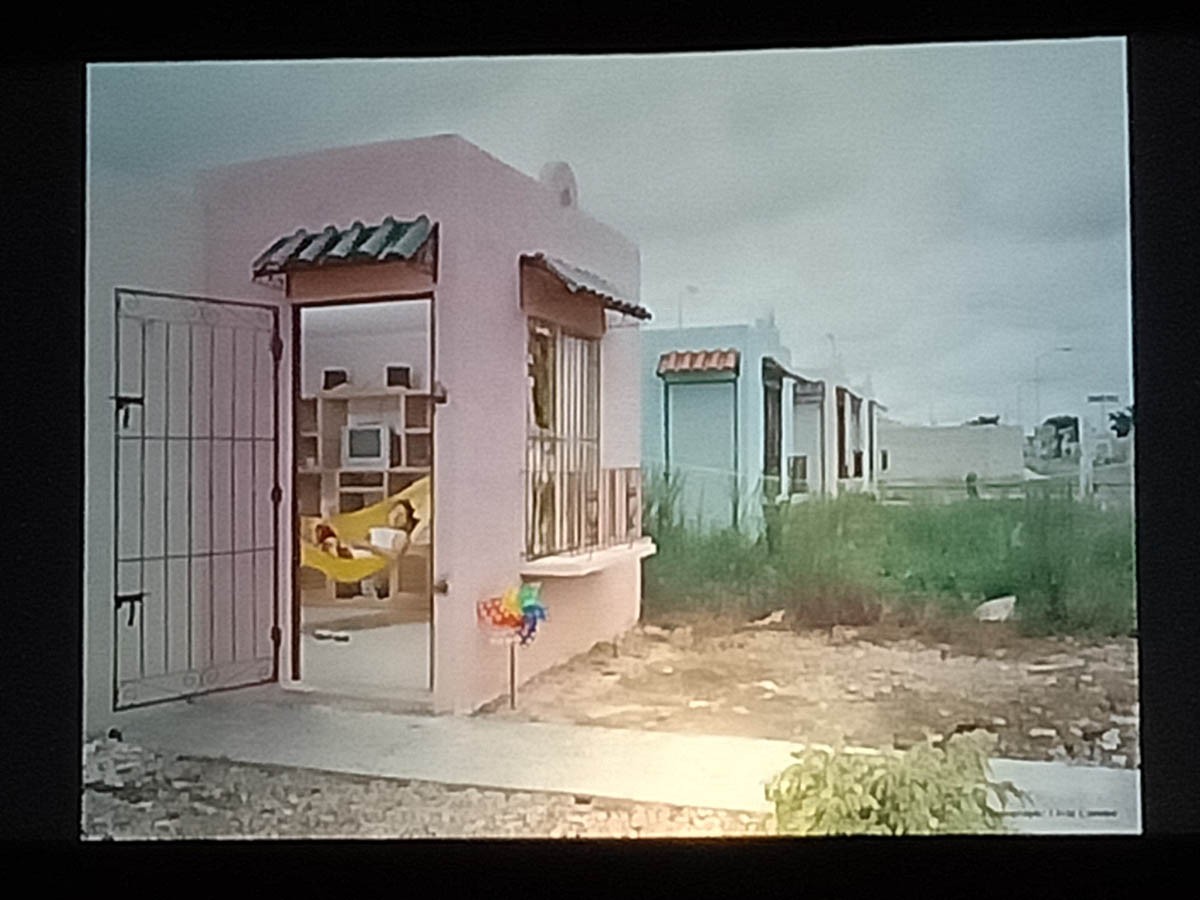

Brijal Brahmbhatt was followed by Tatiana Bilbao, who was not physically present at the conference but joined the audience later for the panel discussion via Skype. Meanwhile, a recorded video lecture played in which she began by discussing the need for housing as a human right, and the efforts of her country, Mexico, to provide dignified housing to each citizen. She took the audience through the history of community housing programs in Mexico, and their inadequacies, followed by horrific models of suburban housing that came up in absentia of any education, healthcare, or civic infrastructure in their vicinity, thereby, aggravating the already overwhelming housing crisis, eventually leading to informal suburban sprawl.

Pointing out health, refuge, and identity as the most urgent human needs, she delved into the need for providing housing designs in proximity to civic spaces and described the challenges related to incremental housing and ownership. She defined the syntax and physiognomy of a house through a user’s perception and its level of relatability to him/her.

"It is very difficult to attain identity if your house looks like 60,000 other houses and your dwelling is just another number," Tatiana’s statements pointed out the limitations in previous housing projects to generate the feeling of a dwelling, an observation proving consequential to her own approach taken as an architect to define a sense of identity in all of her housing projects.

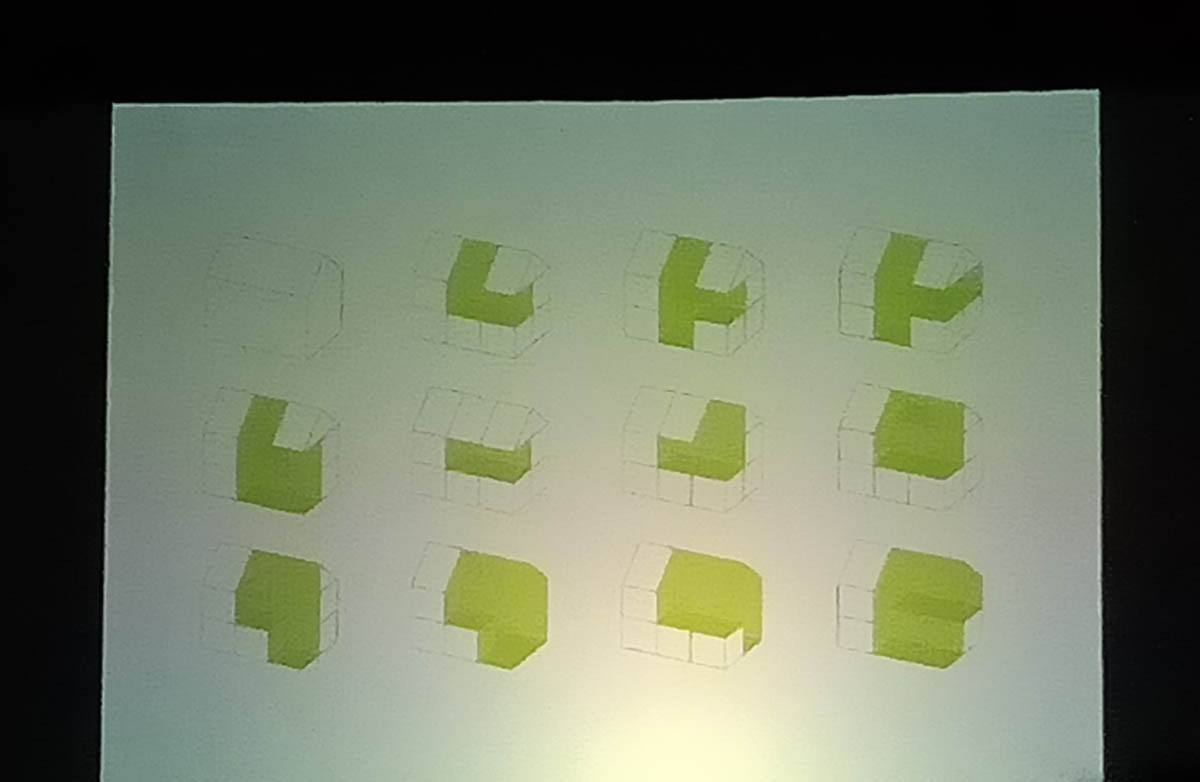

Citing her own works, social housing in Ciudad Acuna, and the $8000 house for Chicago Biennial; she proved how a house can be designed to be configured and adapted according to the future spatial and material necessities of a family without necessarily looking incomplete. The incremental nature of her designs were able to produce twice as much floor space as regular houses of the same cost, and at the same time, generated the archetypical form of a dwelling that made them look complete at every stage, thus, making them desirable and minimal in the eyes of the users while being functionally expansive. Going beyond individual house forms, she delineated a way of thinking expanding on the limits of housing and its conceptions.

Taking cues from her book "A house is not just a house", Tatiana Bilbao revealed more project ideas and strategies that beautifully revealed the fundamental values of living, surpassing individual house forms to express designs of community spaces and external environment, as an inseparable element within her design thinking, evident in La Confluence (Lyon, France). Using the design itself as the method of place-making within a context, and citing excerpts from romantic texts to summarize the meaning of dwelling in a poetic manner, her lecture was construction of a belief that there is a possibility of creating a habitat that is able to balance moments of community, and of personal identification, within a very strict urban environment.

Cino Zucchi began talking about cities with the level of romanticism evident in the manner Tatiana Bilbao closed her talk, creating a seamless transition of emotions to pass the audience. He drew inspirations from images of historic cities, terming them as a ‘second nature’, whose archetype we had lost somewhere during the modernism movement. He talked about the design of historic cities as the exemplification of cultural form and events. The presentation talked about the industrial age, and the nature of strong rational designs of machines-trains, ships, planes, cars that later influenced the architecture of modernism that, due to being individualistic in nature, lost the ability to communicate with architecture in its surrounding, thus creating a discord that was superimposed with dissonant social and cultural patterns piling onto each other to create the modern city, a volcano.

Calling the modern city too, as still nature, having traces of discontent from modernism, the talk titled "city is not a tree" discredited the notion of treating the city as a Unitarian organism - as a reactionary model driven by the guilt of modernist designs. Calling the organic model of a city, hierarchical, and thus, confined to the ego of structure of a single dwelling, he argued for Christopher Alexander’s definition of cities as lattice where each node is writhed to the other in a degree of redundancy, therefore, remaining non-hierarchical – and therefore, the most plausible model according to Cino Zucchi. He expressed streets as living memories and Chandigarh as science fiction, stating that need to adapt on the basis of material culture, changing form, and function was fundamental to a city that always retained a level of genericity to help it surpass its traditional meanings.

Narrowing down to comparison between images of modern spaces designed by architects, and archetypical house forms designed by non-architects, he explained how a dwelling was an object and an architect’s efforts were faced in turning that object into abstraction; while people’s conception was based on creating the object as a manifestation of their memory and perception. On that note, he began explaining his own works that sought to establish the designs as landmarks in places by generating a dialogue, with either the landscape of their domain or traditional forms in their vicinity.

Right from masterplans that created a sense of place in the neighborhood, to facades that were able to generate a public image for themselves by becoming postcards – Cino Zucchi left the audience, humbled with the romanticism and rationale in his designs borrowed from the past, delighted with a presentation full of images and a variety of projects, humored by his style of delivering jokes to express his architecture, and inspired (truly as architects) by his call to bring back emphasis on form and physiognomy to generate equity in built environment – and marking an end to presentations on the topic of ‘housing’.

Henri Lefebvre in his essay "Work and Leisure" in the Critique of Everyday Life, talks about the laziness of certain spaces as a quality that composes people, and puts them in a flux to generate thinking, which over a period of time, is able to move the person beyond the clutter of activities and spaces around him/her and into philosophy of life. This proposition was certainly evident in the monologue "Right of Citizens to have Fun" presented by Shilpa Phadke. Questioning the dullness of public spaces around us she talked about her ‘gender and space’ project that analyzed women’s access to public space and revealed ‘safety’ as a limiting and conditional discourse by mentioning that, “The point is not that I’m never attacked but in case that I am, no one should be able to question my being in that place at that time.”

Her focus was on generating equity in cities by providing access to women in public spaces and places, with the proposition that if space was inviting to women, then space would naturally be sociable enough for other marginalized sections of the society as well. Forwarding the act of ‘loitering’ as a fundamental way of experiencing the city undermined because of any socialist society’s importance given to work, Shilpa Phadke proposed that ‘fun’ thus was a necessary way of claiming the city once again. She read out on the life of working women in Mumbai, the societal bias attached to women accessing public spaces, or loitering in free time, or exploring pleasure and sex.

She further talked about three women movements on the internet that challenged normative boundaries of the society by loitering in spaces that reported frequent cases of gender-based harassment; these movements were – Blank Noise, Girls at Dhabas, and Why Loiter? She further explained how women movements were frequently marginalized as individual neo-liberal measures targeting lower-class men, not that the particular section of men were not the perpetrators in most cases, but because it was very easy for anyone opposing these movements to gain sympathy for the perpetrator on economic grounds and in-turn put the blame on victims by further raising traditional biases, still kept intact by the notions of "safety for women" – also noting that feminist movements were also biased when it came to matters of loitering or sexuality because of a limited sense of articulation on such matters of concern.

Shilpa Phadke’s presentation revealed how the notion of fun today was inextricably linked to the notion of consumption; that our public spaces today remain encroached by capitalism and those that are not remain policed by outdated social accords. She further revealed social bias against the sense of lack of control, and temporal activities, stating that it not only hampered the efficiency of public spaces and limited individual perception. She ended her monologue on a subtle note of irony, stating "Fun is serious business!"

From the perception of freedom and accessibility in spaces, the focus of the presentation shifted to dignity with Sanjit Rodriguez’s presentation on ‘Waste Management’. It is a topic no architect wishes to address. Sanjit Rodriguez served a satirical anecdote stemming from his experience managing waste and recycling campaigns for the tourist state Goa. He talked about the challenges he faced with multi-national food chains and corporations, famous shacks, hotel chains and music festivals operating in Goa.

“Someone has to pick it up, someone has to segregate with no indifference by design, that someone is also human." Sanjit Rodriguez opened up on the apathy design discourses show towards waste management, and that success of such systems was linked to empowering rag-pickers by making their job much easier and cleaner. Terming generation of waste, primarily a behavioral problem, he revealed that the problem was not about international corporations entering Goa, but that they presented no articulation towards the idea of waste management, a plight which was further aggravated by architects, since they refused to incorporate it in their designs or present ideas when the city municipal department called for help.

"We have encroached our land, air, water and forests with waste." In his electrifying presentation, he shifted his focus towards 'my village, my home’ campaign that educates children in primary schools about issues and practices related to waste management; and also guides village panchayats to facilitate the process of household waste segregation and door-to-door waste collection and recycling. Citing design examples from dustbins to compost pits, to waste collection buses, which were designed by the department officials with no help from designers of planners, he presented initiatives and state ideology that has helped them become the most efficient waste recycling-composting system in the world with virtually no landfill site.

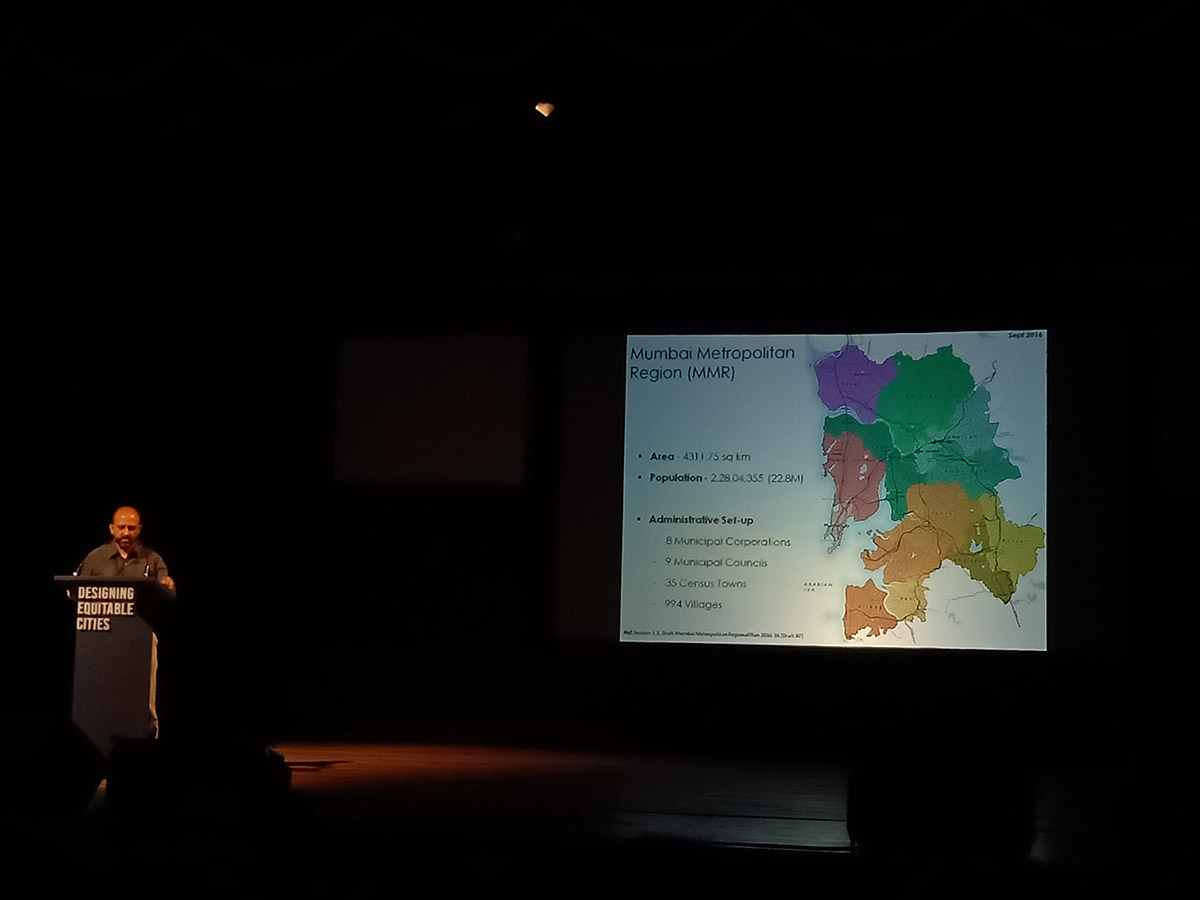

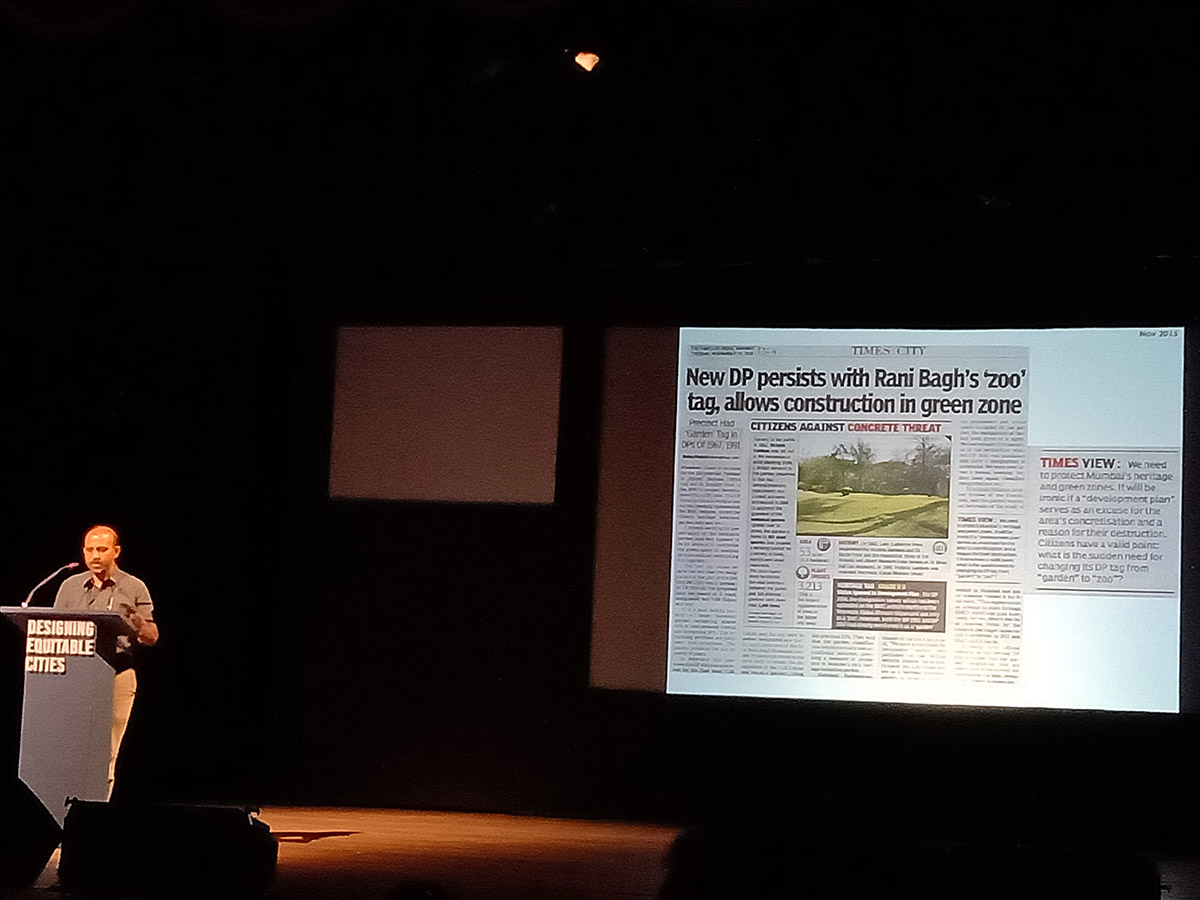

From the challenges and plight of working as a government authority to one of working for a government authority, the transition could not have been made funnier. Pankaj Joshi started his lecture by talking about the capacity building programmes for Urban Design Research Institute in Mumbai, in light of working for the Development Plan for the metropolitan Mumbai. The programme involved identification of stakeholders, discussion at various levels through diverse media, bringing opinions to a consensus for effective decision-making while working on translating key planning and policy projects in Mumbai, to forward ideas of open knowledge and inclusive development.

He further talked about crowdsourcing to collect accurate land-use data, scrutiny of land-use by various groups, and leveraging informal entrepreneurial ecologies for a collaborative and responsive form of governance; disaster preparedness and knowledge dissemination to leverage urban design and planning objectives into other public programmes. This part, according to his experience and the story of working on the Development Plan of Mumbai, was a lengthy, painstaking and arduous process, which led him to explore making recommendations to the Mumbai Metropolitan Municipal Corporation for digital inclusion and communication efficiency for more responsive governance.

His talk expanded on the palpable ground realities of aforementioned points, pertaining to his experience of decision for crowdsourcing data and opting for a participatory process to work on EDDP in Mumbai, accounting for the consequent struggles of each phase, the political ramifications and jargon that ensued, and the imbalanced responses of media while covering the whole story. Pankaj Joshi’s presentation forwarded of the idea of providing the public much-needed ‘dignity’ to voice their suggestions and concerns on the Development Plan of their city of residence on a scale that was unprecedented before the initiative of UDRI; and marked a closure to the topics raised by contingencies, thus, paving way for Heinrich Wolff and Michael Murphy to close the conference with more holistic lectures on the theme ‘Designing Equitable Cities’.

"Structures of inequity run deep and long…Architects and Urban Planning are complicit in way of unequal cities for they have long been monopolizing economic opportunities and marginalizing freedom," began Heinrich Wolff on a grim note. He practices in Cape Town, Africa- a city with the history of Apartheid which he deciphered through curated maps that morphologically explained the condition of inequality in particular neighborhoods. Drawing from the economic theory of externality he explained that economic transactions are of two types, first, positive interventions/transactions, which were caused by disruptive technology that helped in creating network systems, and second, negative interventions/transactions, where a transaction between two groups A and B caused a particular disadvantage to another group C. He found the current state of development to be following the latter trend, and called for the social cost of property development to be worked out and brought to civil litigation.

He talked about reimagining ‘The City of Opportunity’, of undoing economic and spatial inequality, by providing economic dignity to the most vulnerable groups by designing in a manner that is accessible to them- and taking this thought as a point of departure and not the finality. He emphasized on the right to the city, especially movement, where he compared restriction on free movement to a form of slavery and mentioned that it is something that must be brought to public litigation immediately, along with acts like forced eviction that undermine human rights, comparing them to Apartheid.

He went on to talk about ownership and entitlement, where he felt that just legal ownership of space did not socially entitle the person to be acknowledged with the ownership, that there is a particular social clause which needs to be fulfilled to be able to attain ownership. Heinrich Wolff talked about ‘advancement to rights’ for the agrarian non-agrarian populations through which successive generations can be provided incremental entitlement of their spaces, to legitimize their place in the city through smooth transitions; in an effort to try and remember lost social imagination and allow it to be built again over successive periods of time. By doing so, he aspired to take notice of erosion of public culture and memory, and perhaps, conserve it.

He talked about how he, through his practice, tries to imbibe the idea of provisioning and leveraging opportunity by making people, who are related to the network systems of making buildings, a stakeholder in everyday decisions related to design of buildings, training of both skilled and unskilled force, employing local material and technology to building construction – keeping the dichotomy of invention and convention alike while making choices. Heinrich Wolff then showed the audience two classroom experiments executed with drawings and models to visualize the unfolding of a city and its activities through a time-lapse, in order to engage students to imagine the city during different intervals of time.

His arguments from economic research were revealed in his design for a space incubator in which he gave smaller divisions of spaces to individual shop owners within a single market, allowing many small-scale businesses to thrive under one roof, in an economy characterized by hyper-tourism and having the ability to leverage more number of smaller transactions and thus, having the capacity to facilitate a large number of tiny businesses.

Heinrich Wolff ended his lecture by raising the idea of creating social spaces that allowed for a particular social exchange to take place thereby becoming ritualistic in nature and provide memory and value. He expressed the idea of social exchange through the design of a school, where he eliminated corridors to create spaces for interaction that gave the feeling of a public space. The driveway was placed within the school complex instead of being placed at the periphery, to allow parents to part with their kids within the heart of the school, for a social reenactment, thereby, giving a picture to spaces carrying a particular social exchange and social value. He ended his lecture by expressing that, if the design of spaces was done to create economic opportunity and social value to the network of people associated with it, then, cities would start generating more equity and providing dignity to every citizen.

"Power structure inducts us into reinforcing itself. The question is not whether we have an impact but whether we will try to dismantle this power and redistribute it." Michael Murphy’s lecture on beauty and justice drew inspiration from ‘A False Dichotomy’ written by Giancarlo de Carlo. Michael Murphy through his lecture argued that since architecture is always social, as it is always public and touches people and networks, it has the potential role of providing spatial justice. Calling spatial justice a latent power in all architectural works, he emphasized on the moral complexity drawn by architectural systems and argued that its methods should be redesigned to serve the best to the most vulnerable.

The many health-care projects that he explained are exemplary of this proposition. His design expressions reflected emotional reception to the patients allowing them to heal faster, either by providing them comfort through effective response to the climatology of the environment, or creating a sublime material balance through local materials and soothing colors or by giving the view of the landscape to each patient from their bed. Michael Murphy throughout his projects asked the audience to keep dignity as a virtue to invest their decisions in. He talked about assigning values to invisible decisions to restitch resourcing processes with dignity, disaggregated by neo-liberal capitalism. His focus was on building’s that measured human footprint instead of just carbon footprint, "If we design for the dignity of people, we might see results we have never seen before."

To explain his design for the National Memorial of Peace and Justice he informed the audience about the history of the American Civil War, the genocide of Blacks, conditions of slavery, the deeply hurtful memories that scarred the present socio-political condition of the USA, and the false narrative purported by keeping the public memories of Confederation in place. To counter that, he designed the museum in a way, that all tablets, each bearing the name and information of one of the victims of slavery, that lie fixed in the steps surrounding the building, will be taken out and fixed in a city to remind them of the struggle of those individuals, to forward the correct narrative of the history of slavery in America.

In another example, the Holocaust Memorial Project, visitors will be invited to take one of the stones from the memorial’s central space, back with them, as a reminder of their commitment to fight intolerance, inequality, and injustice. By doing so, he purposefully made the design vulnerable by keeping it open to subjective experience but also gave it the possibility of remaining alive within the memory of thousands of people and transcending the barrier of place to generate a ritualistic enactment within the society.

This scope of ritualistic enactment was also revealed in his design for the National Memorial of Peace and Justice, which collected soil samples in big jars, from all those places that witnessed atrocities against African Americans during the civil war. By calling for samples from different places, the very act brought alive stories of struggle, regret, and redemption, thereby generating many social narratives regarding the project and finding a relevant place in public memory and steering the collective memory and public narrative on slavery in the right direction.

"Architecture is not the only form of justice, but, to begin with, we need to name it and spatialize it" Michael Murphy ended the conference on this note, emphasizing of providing dignity to people through physical intervention, political expression, and memory.

The talk was filled with passion and was steered with eloquence from one moment to another, exhuming voices of Michael Murphy’s design subjects and awakening spirits of the audience that, at the end of the lecture, recognized his words with a long applaud. His powerful notes were able to evoke emotions in each individual, to respect human potential, and fight inequity in all aspects that define society, through physical intervention in space, or objects, or programmatic dialogues that were revealing of lost narratives. The end of his lecture was followed by a lengthy panel discussion with Heinrich Wolff, moderated by Rahul Mehrotra.

The Z-Axis 2018 had through the last talk, provided an excellent motivating closure to the idea of "Designing Equitable Cities" by helping all students and practitioners understand the most crucial aspect of any architectural intervention or spatial exchange, be it for any function or any place – defining memory of a person and injecting dignity into it, and developing a morally plausible and scientifically truthful narrative in a culture. With this, the third edition of Z-Axis 2018 organized by Charles Correa Foundation came to an end.

All images © Tarun Bhasin