Submitted by Asmaa Kamaly

The art and architectural legacy of the architect Ramses Wissa Wassef

Egypt Architecture News - Jul 11, 2022 - 12:31 5919 views

Art could be seen as a problematic subject that can not be easily defined since it tends to be more elusively subjective than objective. Most people have an array of definitions regarding what is art. Art movements were initiated to convey different and often contradictory perceptions related to art in various eras. Sometimes the beneficiaries and creators of the art works have been confined to certain social strata. However, all the social groups have the needs and ways to simply and precisely express themselves. These needs might be for various purposes1 including religious ritual, commemoration of an important event, propaganda or social commentary, recording of visual data, creating beauty, storytelling and communicating intense emotion.

Some argue if art is reclusive from the society or integral in some senses. Can art based works including architecture impact the society?. Or, is it completely detached from the surrounding?.

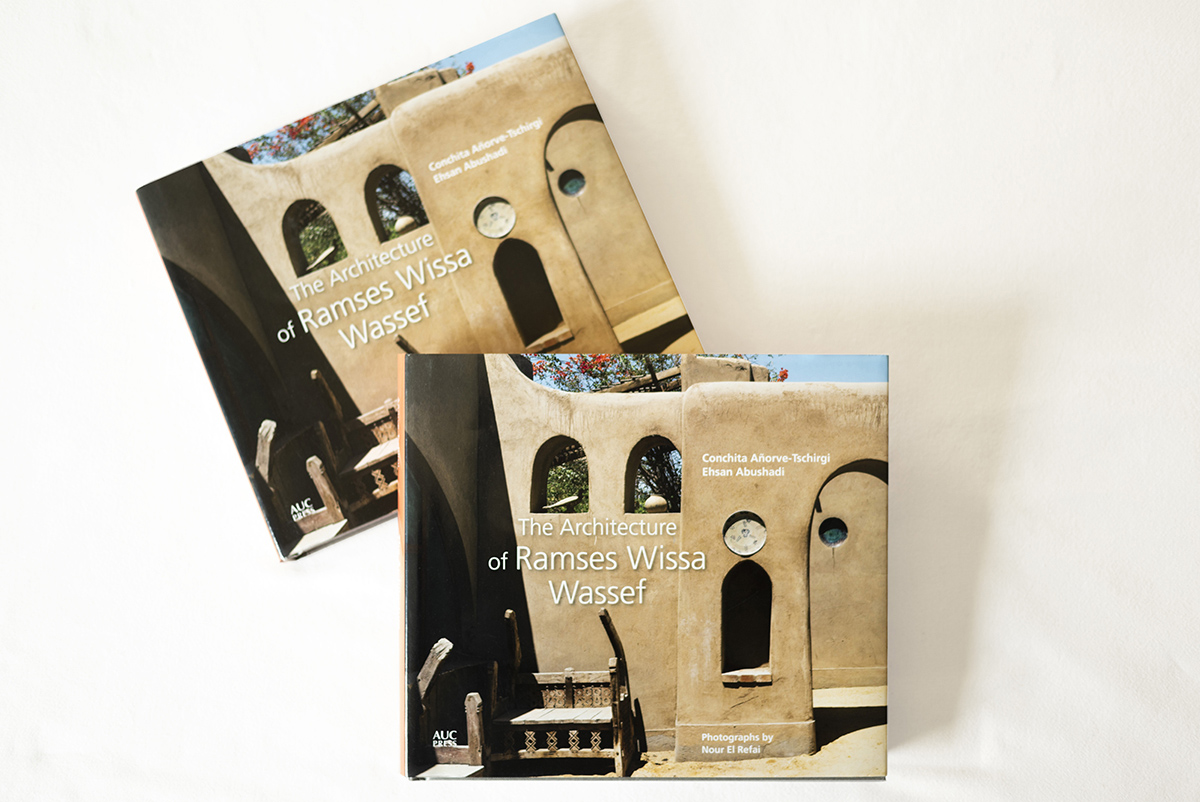

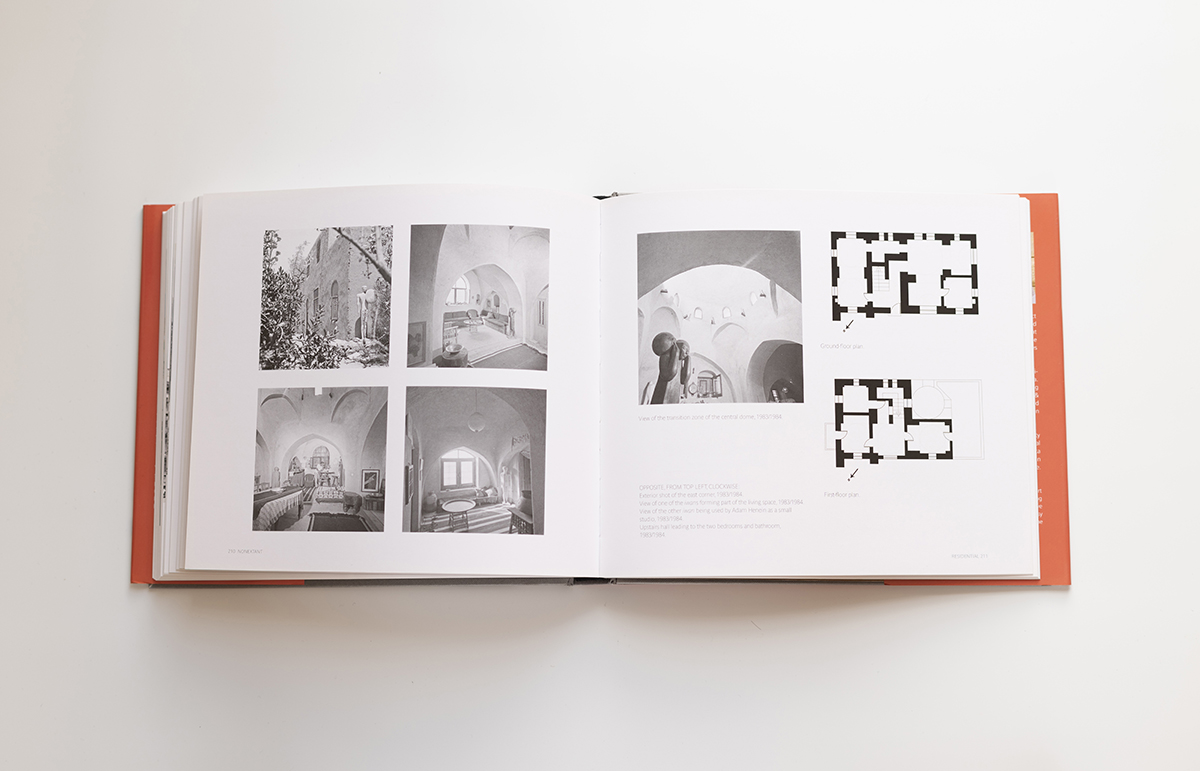

In Egypt, there is both an art and architectural legacy of the Egyptian Coptic architect Ramses Wissa Wassef that have been documented and published in the book of Ramses Wissa Wassef architecture published by AUC press. The Ramses Wissa Wasef Center was awarded the prestigious Aga Khan award. The centre was founded in the early 1950s by the renowned archtiect as a weaving school. The architecture mainly was the vaulted and domed mud brick structures expressing something quintessentially Egyptian as these forms had been adopted in turn by Paranoiac, Coptic and Islamic civilisations. The jury acclaimed the centre for "the beauty of its execution, the high value of its objectives, the social impact of its activities as well as the power of its influence as an example." The project is perfectly adapted to its environment, enhancing the role of earth as a building material and demonstrating innovation in the organization of volumes and its subtle use of light. The Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center, a social as well as a sculpture and spiritual dimension, as it has proved. A place supportive as well as poetic or supportive because it is poetic, where the young tapestry weavers of the community have been free to develop an artistic hand craft, producing tapestries of great excellence and renown.”

Ramses Wissa Wassef paid specific attention to children and he involved children as key stakeholder and partners in the developmental projects quoting him, "Human freedom never has as much meaning and value as when it allows the creative power of the child to come into action. All children are endowed with a creative power which includes an astonishing variety of potentialities. This power is necessary for the child to build up his own existence.”

In this article we spoke to one of the authors of the book of of Ramses Wissa Wassef architecture to discuss the book and explore more the projects of the architect Ramses Wissa Wassef.

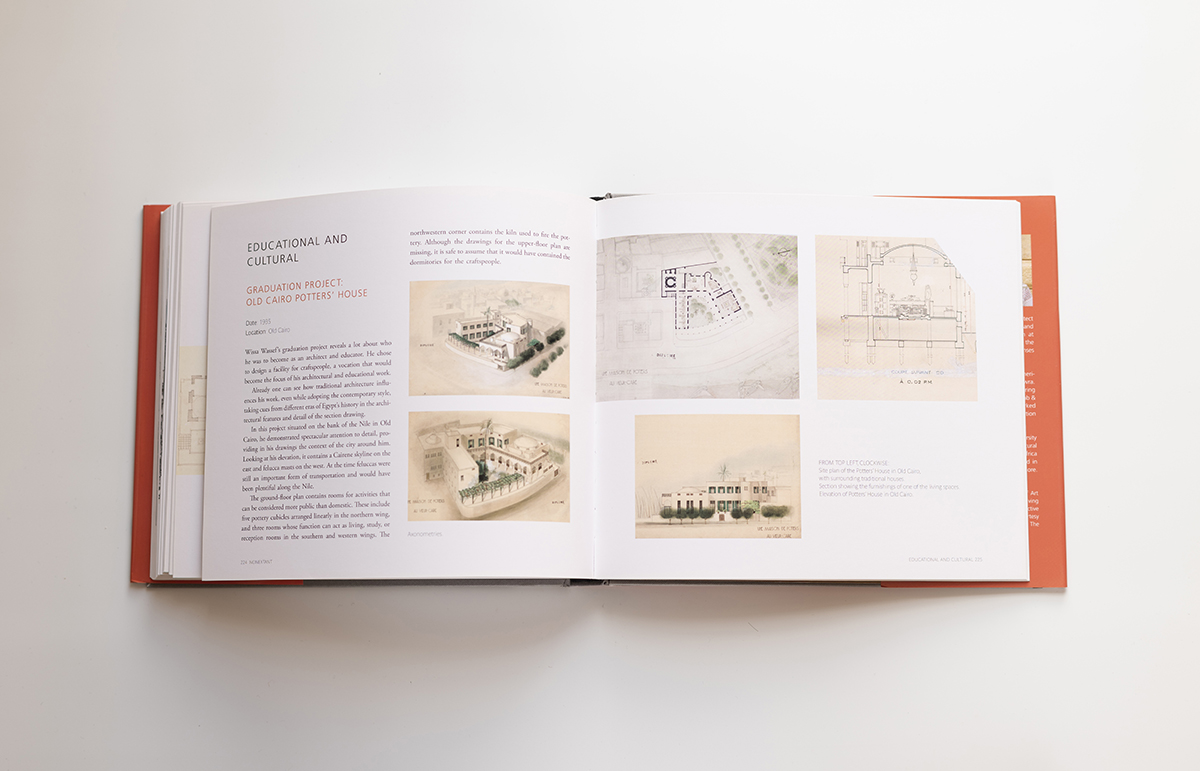

Asmaa Kamaly: Given that Ramses Wissa Wassef grew up in a prominent upper-class family, where did his interest in Egyptian heritage, first reflected in his graduation project Old Cairo Potter’s House for the École des Beaux Arts de Paris, and later on in his other projects, come from?

Ehsan Abushadi: The upbringing Ramses Wissa Wassef’s parents provided to him and his siblings was an important factor. They emphasized Egyptian culture and heritage in a time when there was a lot of European influence in Cairo, particularly among prominent families and the arts. They also nurtured the arts among Ramses Wissa Wassef and his siblings, with each of them mastering a variety of artistic disciplines like music, sculpting and painting.

His father, Wissa Wassef El-Beblawi was himself a patron of the arts, being involved in the cultural scene. He was also active in politics as a prominent leader of the Wafd party. As a result, Ramses Wissa Wassef grew up discussing socio-political and cultural challenges that Egypt faced, a trait that carried on into adulthood, influencing his socio-architectural projects and pedagogy.

Asmaa Kamaly: Considering the integration of stained-glass stucco windows in many of his design projects in addition to his work in decorative elements and furnishings, do you think Ramses was more an artist than architect?

Ehsan Abushadi: Ramses had multiple interests and was proficient in a variety of arts, as well as in architecture. I do not think it is a question of whether he was more of an artist or an architect, but rather how he excelled and shone in the marriage of the two. In this book we give a short introduction on who he was as both artist and architect. In his architectural projects, one can detect how his artist mindset informed and influenced the architectural form, independent of the inclusion of artistic elements and decorative arts into his work.

Asmaa Kamaly: Ramses Wissa Wassef was undoubtedly inclined toward the Egyptian tradition and opposed to the widely acclaimed Haussmann architecture and classical models of the time. He was an active member of the Friends of Art and Life collective and contributed to establishing guidelines for the design of contemporary churches. Nevertheless, he also built modernist buildings with minimal lines. Can you elucidate his stance toward the architecture movement at the time?

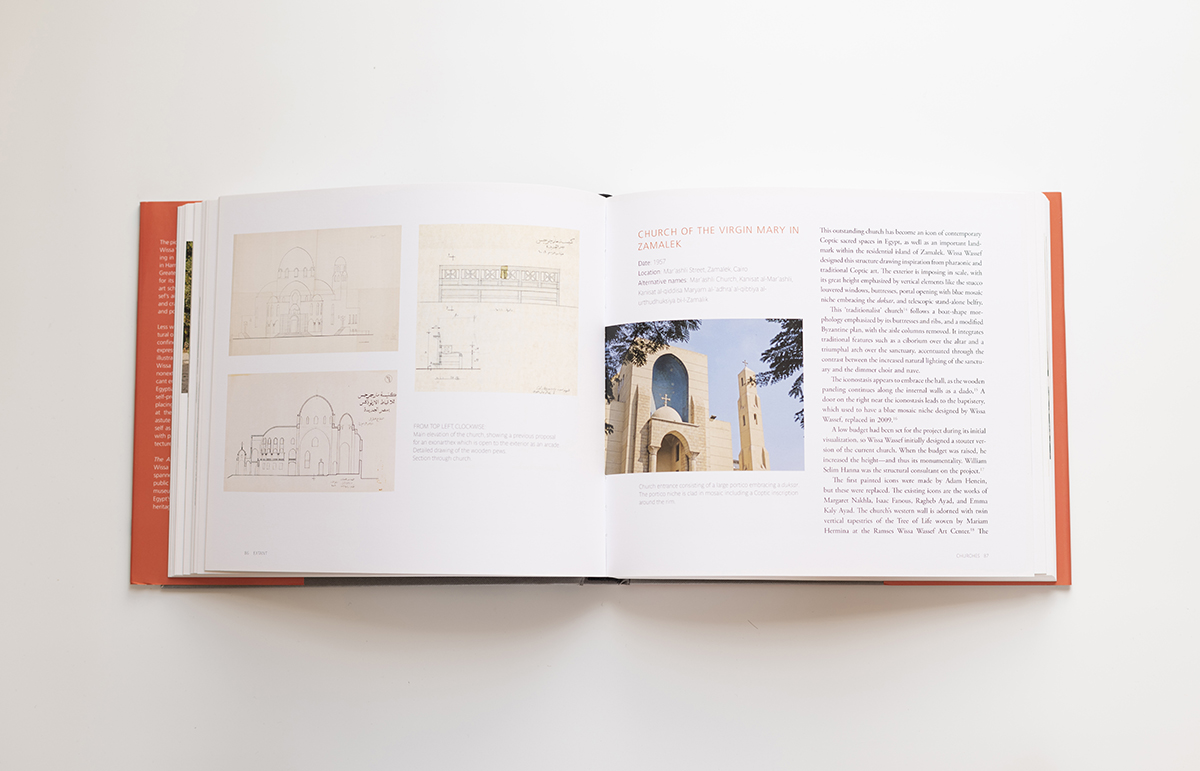

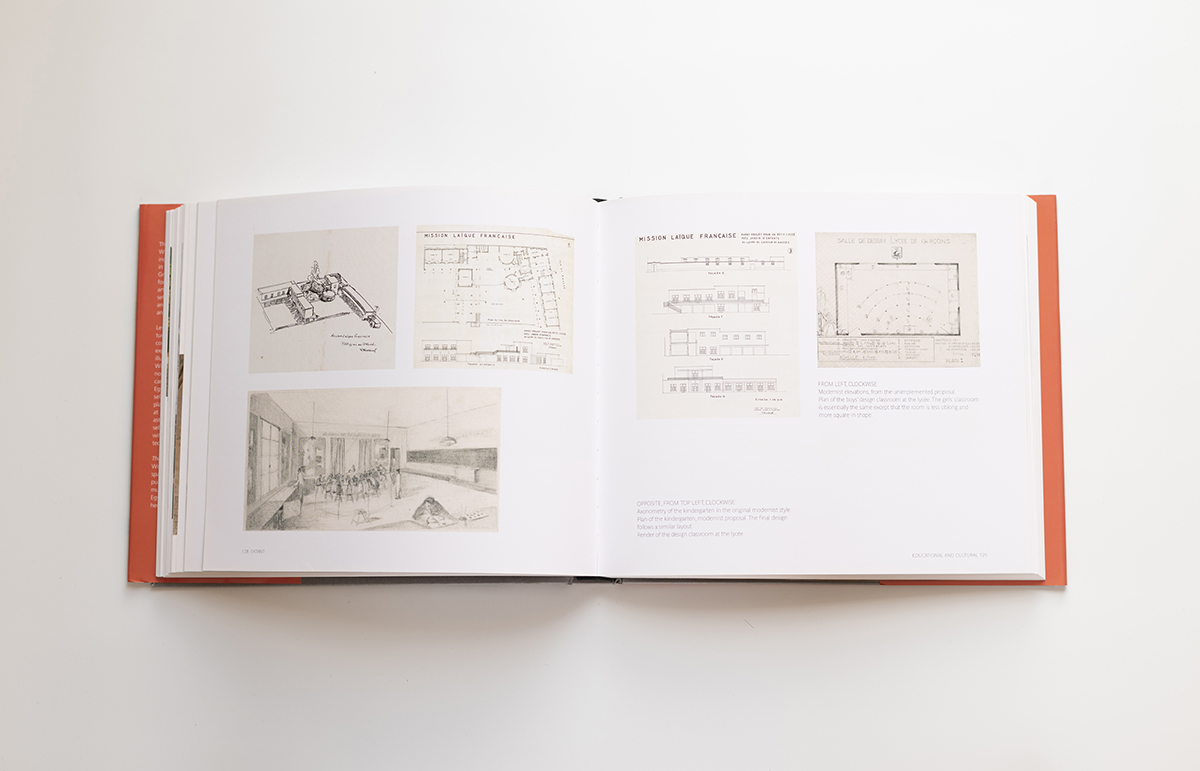

Ehsan Abushadi: There is a widespread one-sided perception that Ramses Wissa Wassef’s architecture is limited to the traditional and vernacular. This is mainly attributed to a lack of awareness regarding his works beyond the Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center (1952-1972). His other famous works, such as the St. George and St. Abram Church in Heliopolis [Mar Girgis Church] (1954), the Church of the Virgin Mary in Zamalek [al-Mar‛ashli Church] (1957), and the Mahmoud Mokhtar Museum (1960), are often perceived as deviations from his “true architecture” which many believe to be manifested in the arts center. However, his interest in the traditional does not negate modernist elements.

Many of his original designs for residential buildings or churches feature very minimal lines. While this stylistic choice aligns with modernist principles of designs, it is also an integral element of traditional residential architecture and Coptic churches and monasteries. Given the similarity between the two, what makes his designs contemporary is his reinterpretation of the traditional to create new innovative designs and forms that seem familiar while integrating other modernist principles related to layout, contemporary living, ventilation, and natural light.

Due to limited correspondence and other personal written material in his archive, we cannot be sure what his personal viewpoint was, however, his designs can tell us about how he explored a combination of Egyptian traditional and modern architecture. Some projects equally balance the two, while others shift the scale towards one over the other. Although he graduated from the École des Beaux Arts de Paris in 1935, where he studied neoclassical architecture such as that of Haussmann and the classic orders, this architectural approach was past its peak and starting to lose traction in 20th century architectural practice. Despite his reputation for traditional or vernacular architecture, he truly mastered creating a contemporary Egyptian architecture.

Asmaa Kamaly: Ramses Wissa Wassef was acquainted with the renowned architect Hassan Fathy. Both architects shared the ideals of sustainable and climate responsive architecture, inspired from Egyptian heritage, even before the term was widely conceived in the architecture/urban field. Was there an Egyptian heritage-based architectural movement at that time?. Did this relationship influence the architectural perception of Egyptian heritage within Egypt?

Ehsan Abushadi: Ramses Wissa Wassef and Hassan Fathy were more than acquaintances; they were great friends that met frequently for tea and walks, during which they would engage in long conversations on a variety of topics. Although their only known architectural collaboration is the Faruq I University Dormitory (1945), they worked together to change the way architecture was taught at the Faculty of Fine Arts where they were both professors, as well as serving terms as elected department heads. They did so by implementing a three-atelier system similar to the École des Beaux Arts de Paris.

Together, they went on the infamous 1941 Faculty of Fine Arts trip to Upper Egypt which greatly impacted both their architectural trajectories. Their interest in the Egyptian arts and heritage, climate responsive architecture, and local materials were perfectly aligned with the views of the Friends of Art and Life group of which they were both members. Founded in the 1930s by Hamed Said, this group was part of the movement promoting an Egyptian identity in the arts, traditional crafts, nature, and relations created between people and the environment.

Asmaa Kamaly: The Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center in Harraniya is considered the realization of Ramses Wissa Wassef’s graduation project with an emphasis on reviving arts and artistic practices such as weaving. Could you summarize the phases of this project?

Ehsan Abushadi: Ramses Wissa Wassef’s graduation project, the Old Cairo Potter’s House (1935), aimed at providing a specialized residence, workspace, and learning space for potters. He would design two other projects following the same premise: the School for Art and Handicrafts in al-Qubba (1947) and the Ramses Wissa Wassef Arts Center (1952-1971, with posthumous additions), of which only the latter is extant. However, the School in Old Cairo (1941) can be considered a pilot project. Much smaller in scale, he built this four-dome school where he started teaching weaving to children. The program was discontinued when the school management changed, causing a shift in learning scope and activities.

The Ramses Wissa Wassef Arts Center was built in phases, based on growing pedagogical and family needs, funding, and land purchases. The book contains a detailed description of the various phases and modifications implemented by Ramses Wissa Wassef, as well as his brother-in-law Badie Habib Georgi, son-in-law Ikram Nosshi, and grandson Ramses Ikram Nosshi.

However, it can be summarized as follows:

- Village Art Studio and Gallery—Phase 1 (1952-53, Modified In 1961, 1978, 1979-1980, And 1989)

- Solar Kiln (1955-56)

- Village Art Studio and Gallery—Phase 2 (1962, Modified In 1965-66, 1968, 1970-71, And 1978)

- Chicken Coops and Toolshed (C. 1962-63, Modified C.1968-69, And 1974-75)

- Habib Georgi Museum (1967-70, Modified In 2009)

- Silos (C.1969)

- Cérés Wissa Wassef Villa (1970)

- Seven Weavers’ Houses (1970, Modified In 1977 And 1994)

- Second-Generation Weaving Workshops (1971)

- Engineer Mounir Nosshi Villa (1971, Modified In 1994)

- Temporary Chapel (1972)

- Posthumous:

- Silo with Spiral Staircase (1975)

- Tapestry Workshop Expansion (1978)

- Ikram Nosshi and Suzanne Ramses Wissa Wassef House (1983)

- Permanent Tapestry Collection Museum / Ramses Wissa Wassef Museum (1989)

- Storage Building (2012)

Asmaa Kamaly: The art center not only focused on reviving arts but was also attuned community needs through facilities and services such as the health clinic and canteen. Could you elaborate on how Ramses Wissa Wassef pursued human centered architecture?

Ehsan Abushadi: Ramses Wissa Wassef put people first in his designs, which manifested in various forms from passive climatic control that ensured comfort, ergonomic features, and furnishings, to programmatic decisions that aimed to improve the quality of life whether socially, educationally, or physically.

In the case of the art center, these were often interweaved with pedagogical approaches to obtain a wider impact. As such, not only did he provide specialized learning spaces but offered the chance to learn to build such structures. The canteen fed his students but also served as a space where his wife, Sophie, offered nutrition education. Additionally, a clinic was set up to compensate for the lack of medical care, but extended its services to the whole village.

Asmaa Kamaly: The relationship Ramses Wissa Wassef had with his students was considered to be a remarkable one. As written in the book, when the famous architect started his work in Harraniya, some of his students—most of whom have turned out to be prominent professional artists—followed him there turning the area into an artistic node. Could you further explain how he saw his role as a professor?

Ehsan Abushadi: We cannot really know what he thought of himself as a teacher, as his archive is mostly comprised of architectural drawings and a few papers related to his projects. However, based on what his students have relayed of him, and his genuine interest in pedagogy which he extended to various architectural projects, we know that he was very invested in his students and made a life-long impression on them. His commitment to their learning took on various forms including personally drawing visual teaching aids to enrich his lectures. He even offered continued mentorship and support to some of his students after they graduated.

Asmaa Kamaly: The book mentions how Ramses Wissa Wassef included children in his architectural participatory designs and experimentation. Could you elaborate?

Ehsan Abushadi: The Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center is mainly known for teaching weaving; however, other crafts were taught there including pottery, stoneware, mud-brick construction, and later batik. Local builders learnt mud-brick construction when Ramses Wissa Wassef paired them with expert builders from the Abu Alaa family of Kafr al-Naggar and Kafr al-Mahamid in Aswan, more famously known for having built Hassan Fathy’s New Gourna. During this exchange, children aged 14 to 16 learned by observing them until they were ready to put their knowledge into practice. Wissa Wassef would then introduce the children to practical training by having them build chicken coops which accommodated to their height and skill level. This was followed by the construction of a toolshed.

When the children at the center grew into adults, Wissa Wassef facilitated their economic security by encouraging them to own a plot of land on which to build a house. He then asked them to model their houses out of clay as a means of engaging them in architectural participatory design. Based on these clay models he designed the Seven Weavers’ Houses (1970).

Asmaa Kamaly: Some of the weavers left the houses Ramses Wissa Wassef had built for them. Could you indicate the reasons behind this and any other setbacks faced by this residential project?

Ehsan Abushadi: The Seven Weavers’ Houses (1970), located within the center on the border with the Harraniya village, were not completed by the time Ramses Wissa Wassef passed away in 1974. By the time they were completed by Badie Habib Georgi in 1977, there will likely big changes to the weavers’ family size, needs, and circumstances. Therefore, it would not be surprising that the weavers moved to other locations whether inside Harraniya or elsewhere.

It is also worth noting that the weavers started learning at the center as children, so by the time these houses were built the first-generation weavers would be in their late 20s or early 30s. Hence, I would say that the weavers leaving these houses is probably more related to personal and family circumstances rather than an indicator of the functioning of the Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center.

Asmaa Kamaly: The Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center in Harraniya and its products are internationally recognized and considered a successful project. What are the factors that led to its international success?

Ehsan Abushadi: The international recognition of the center’s success is due to two things. The first is all the international exhibitions in which the center’s tapestries were displayed, the first of which was in Basel, Switzerland (1958). Over the years the center has been highly active in this respect and continues to participate in international exhibitions to this day.

The second factor was the prestigious Aga Khan Award for Architecture, which was presented to Ramses Wissa Wassef posthumously in 1983 for his multifaceted development of the center on architectural, social, and pedagogical levels.

Despite this recognition, a lot of his architectural work has largely remained unknown both nationally and internationally, which led us to write The Architecture of Ramses Wissa Wassef, the first book dedicated to his architectural repertoire.

All input and images via Nora Abushadi.

1. Various purposes. Please click on this link first: https://www.facebook.com/186554311364293/posts/httpchartxacornelleduartintroarthtm/10153829971405022/ and then click on this link on Google Chrome: http://char.txa.cornell.edu/ART/introart.htm