Submitted by WA Contents

Richard England explores "Architecture and the Senses"

Malta Architecture News - Aug 15, 2018 - 03:19 39664 views

Maltese architect, writer, artist, academic and Honorary Member of World Architecture Community Richard England, explores "architecture and the senses" with a series of images in this exclusive essay, starting from the historic buildings to the present examples of architecture.

Text by Prof. Richard England

"Whatever space and time mean, place and occasion mean more" - Aldo van Eyck

We are well aware that the appearance of architecture is important, yet more important is how its spaces and ambiances affect us as users. Architecture is not only experienced visually, but more so holistically through all of our five senses in a haptic manner that extends our sensations well beyond our retinal imagery. The French poet and philosopher Paul Valery, in his book ‘Eupalinos or the Architect’ speaks of the appearance of architecture, but more of how buildings can move their users. In an Ancient Greece Platonic dialogue between Socrates, Phaedrus and Eupalinos, the latter refers to buildings which are “mute”, some which “speak” and the rarer ones which "sing".

Buildings emanate emotional intensity through our experience of their spaces; for space, being mood manipulative influences and energises our feelings and reactions. However, establishing exactly what it is that makes a building “sing” and in turn moves us, still remains difficult to identify or define.

The oldest and perhaps best definition of architecture comes from the Roman architect Vitruvius in his ‘Ten books on Architecture’ (30-20BC) “utilitas, firmitas et venustas” i.e. utility, firmness and delight. “Utilitas” accommodates the materialistic functional needs of a building, while “firmitas” refers to its engineering stability; i.e. that a building is well constructed structurally. These two qualities however, produce solely construction and not architecture. For construction to be elevated to the level of architecture and produce buildings which “sing”, it is necessary to add the third element of Vitruvius’ definition “venustas” (beauty), as was also emphasised much later by the Modern master Le Corbusier, “you employ stone, wood, concrete and with these you build houses …that is construction. You touch my heart …that is architecture”.

However, defining beauty and how it is applied to make a building “sing” remains difficult to identify. Vitruvius proposes that for buildings to possess the quality of beauty, they should be designed with a sense of order and based on proportions found in nature and on those of the human body. However, beauty itself also remains difficult to define. Dostoevsky correctly pointed out that “beauty is mysterious” and philosopher Roger Scruton’s definition as “exhilarating, appealing, inspiring, calming” and also “consoling, disturbing, sacred or profane” is equally complex. Complications further arise when we are told that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” and that our concept of beauty varies and changes over time. Despite our inability to define beauty, we are fully aware that beauty always seems to provide us with a sense of comfort and well-being.

To understand our reaction to architectural space, it is necessary to examine how we sense, perceive and conceive space and how space in turn activates and influences us; i.e. how the geography of the mind and body reacts to the geography of space and place and vice versa, and how our presence in a particular space affects our moods and feelings. While it is widely believed that architecture is sensed only visually, this is far from the truth, since we comprehend far more than what we see, as our whole body is constantly acting as a sensor. We respond to space, in a space-time equation, through our physical movement in the passage of time.

All of our five senses; visual, haptic, aural, olfactory and oral, act as gateways to the mind. There is however also a sixth sense; that of our overall reaction to the atmosphere of space incorporating our total sensual response to a space with all of our senses; seeing, touching, hearing, smelling and tasting. This is our total sensory reaction which geographer Yi-Fu Tuan in his book ‘Space and Place’ describes as “ranging from inchoate feeling to explicit experience” while coining the phrase ‘Topohilia’ to describe positive reactions to space and place.

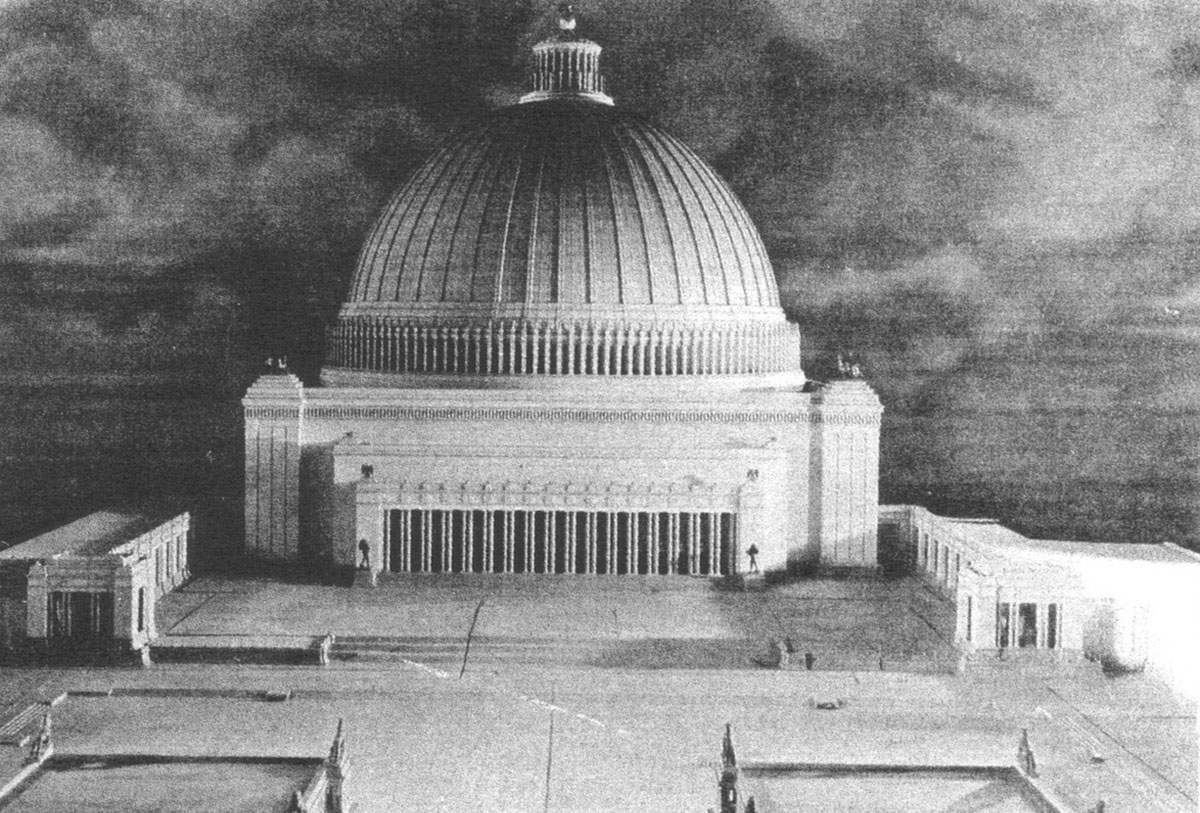

The Great Hall of the Reich, as planned by Albert Speer. Image courtesy of Flickr/Marten Kuilman

The destruction of Pruitt-Igoe. Image © St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Architecture may be considered as the third skin of our body, our natural envelope skin, being the first and clothes the second, which provide insulation the second. As such, the third skin affects our mind, brain and nervous system either positively or negatively depending on the pulsations it receives. Sculptor Anthony Gormley says that "we feel pleasure and protection when our body resonates with a space”, and author Alain de Botton in his ‘The Architecture of Happiness’ stresses that “a good building can change your life and a bad one, ruin it". Philip Johnson further adds that "great architecture is the design of space that contains cuddles, exalts or stimulates the persons in that space”. When a space which we are in resonates with meaning that it becomes place and we then react positively to it.

Maggie's Centre by Lily Jencks in collaboration with Harrison Stevens in Glasgow, Scotland, UK. Image courtesy of Lily Jencks Studio

Maggie's Centre by dRMM in Oldham, England. Image © Alex de Rijke

Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa in his ‘The Eyes of the Skin’ a publication which is now required reading in architectural schools, addresses the role of how our body, with its senses as loci of perception, reacts in relation to how we experience architectural space. The book pioneered the understanding of the phenomenological response of our body to its physical surroundings, echoing the earlier writings of Rasmussen and Gaston Bachelard, who in his classic ‘Poetics of Space’ had already referred to “the polyphony of the senses”. Phenomenology adds meaning making to our experience of architecture. While it is a fact that people may not necessarily think of architecture, they still feel it, and consequently are influenced by it. Architect Richard Rogers confirms this when he says “I believe we architects can affect the quality of life of people”.

Harmony, proportion, number, measure and order have for long been cited as the necessary qualities for an architecture of beauty by Pythagoras, Vitruvius, Alberti, Filarete, Palladio, Leonardo da Vinci, Le Corbusier and others. Yet no Golden Section, Fibonacci or Modulor formulae application will ensure a well-designed or soul-enhancing edifice. While the solution may not be a mathematical one, enhancing architecture may perhaps be more dependent on the capabilities of the project’s designer and on the passion, commitment and love that is put into its making. Spaces conceived with dedication, commitment and love absorb and retain these energies and then pass and convey them to their users. It was Mother Teresa who said that “more important that what you do is the love that you put in the doing” and Belgian painter Erik Pevernagie also stated that “love has the power to create an inviting space in the lives of people”.

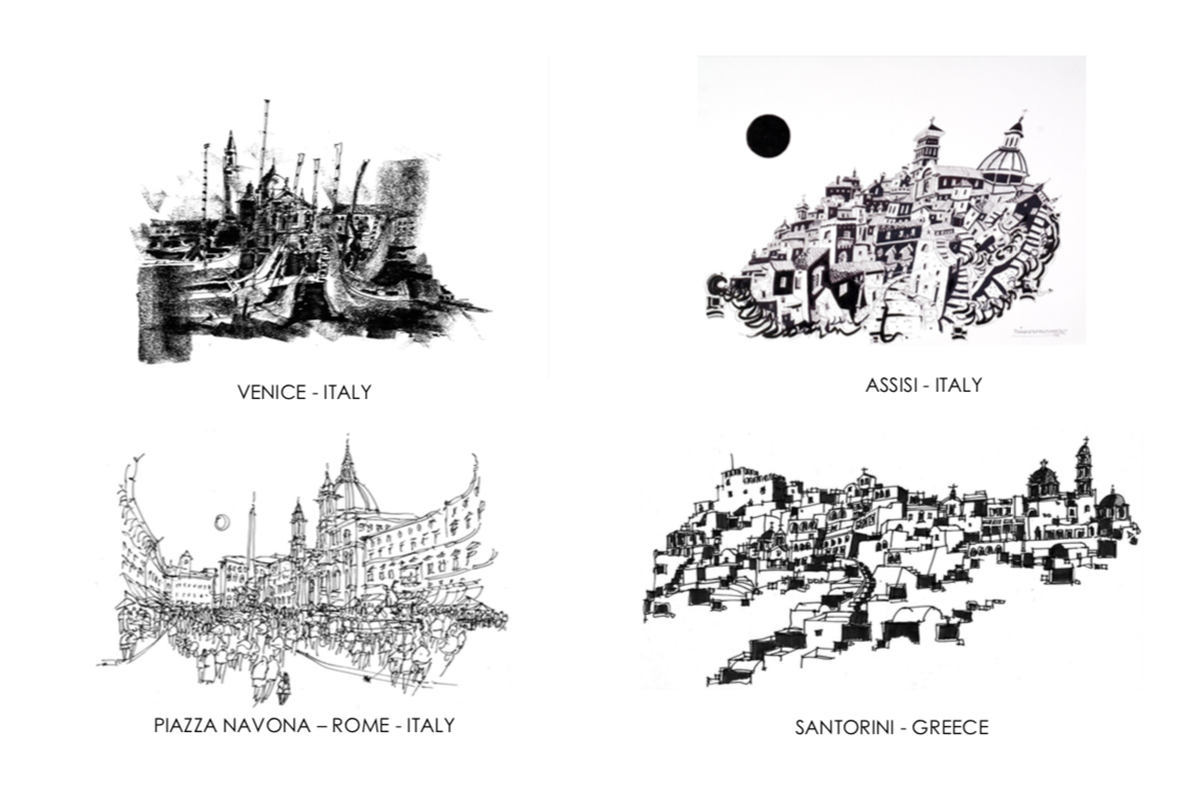

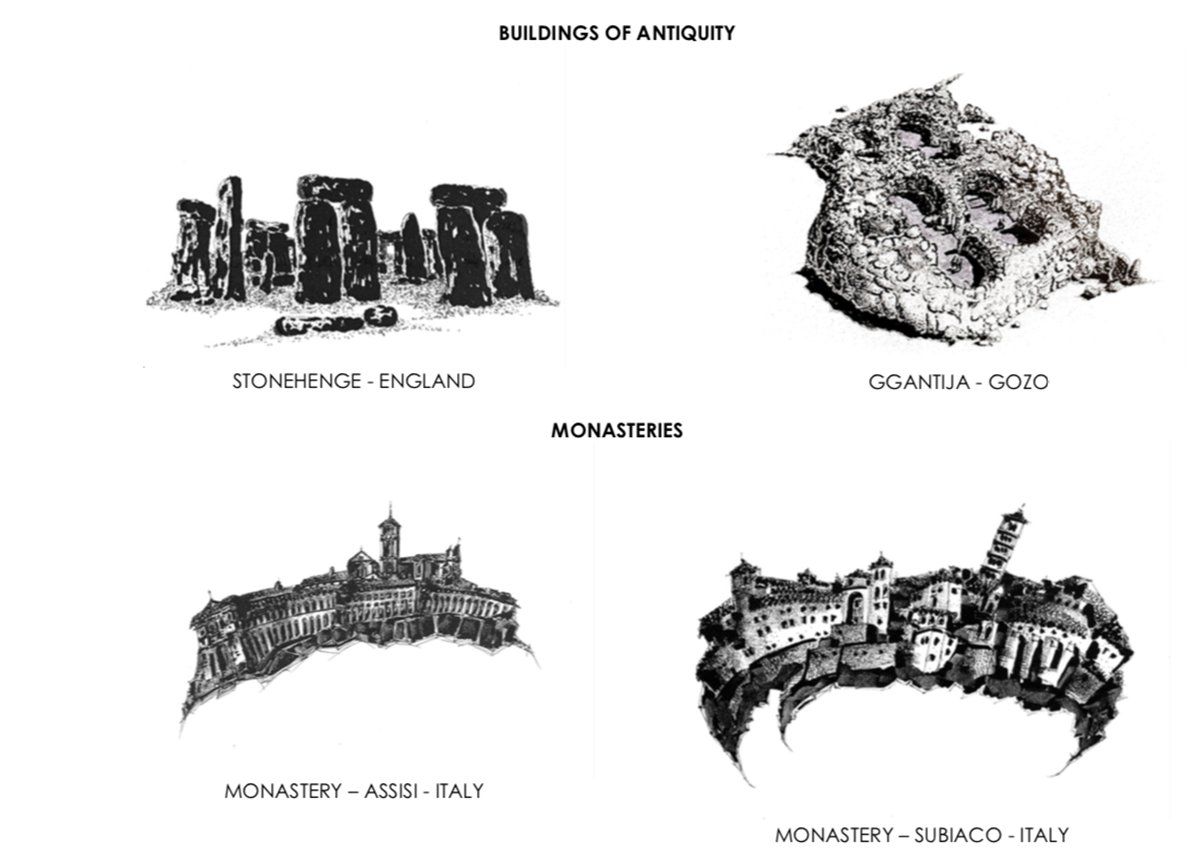

Confirmation of this is demonstrated in the buildings of monasteries, priories, cloistered spaces and sacred buildings, including those of pre-history; all fashioned with love, dedication and an overlays of religious fervour. These are buildings which emanate convivial atmospheres, empathy and ambiances suited for meditation, prayer and ritualistic gatherings. Ancient sacred buildings seem to possess palpable, physical and psychological energies, perhaps because, as Einstein stated “the ancients knew something which somehow we seem to have forgotten”.

The sites of pre-history’s temple edifices seem to possess and emanate inherent earth energies. It seems that ancient man was able to tap these energies perhaps because, human relationship with nature in those times was a more compatible one and that for the ancients, land had more meaning. This demonstrates that space is not only a physical entity, but more so an energy filled milieu. Monastic spaces designed to be conducive to reflection and prayer, with their cells as guardians of silence and solitude; all provide ambiances in which one is coaxed towards reflection and spiritual meditation. They are also spaces where one’s perception of time and space is altered. Jonas Salk, long struggling to solve the Polio puzzle, eventually deciphered it in the contemplative ambiance of an Assisi monastery. He later claimed that the silence and solitude of his monastic enclave were instrumental in inducing a sense of calmness which in turn, sharpened his thought process.

Cards On The Table: The Architecture Of Richard England

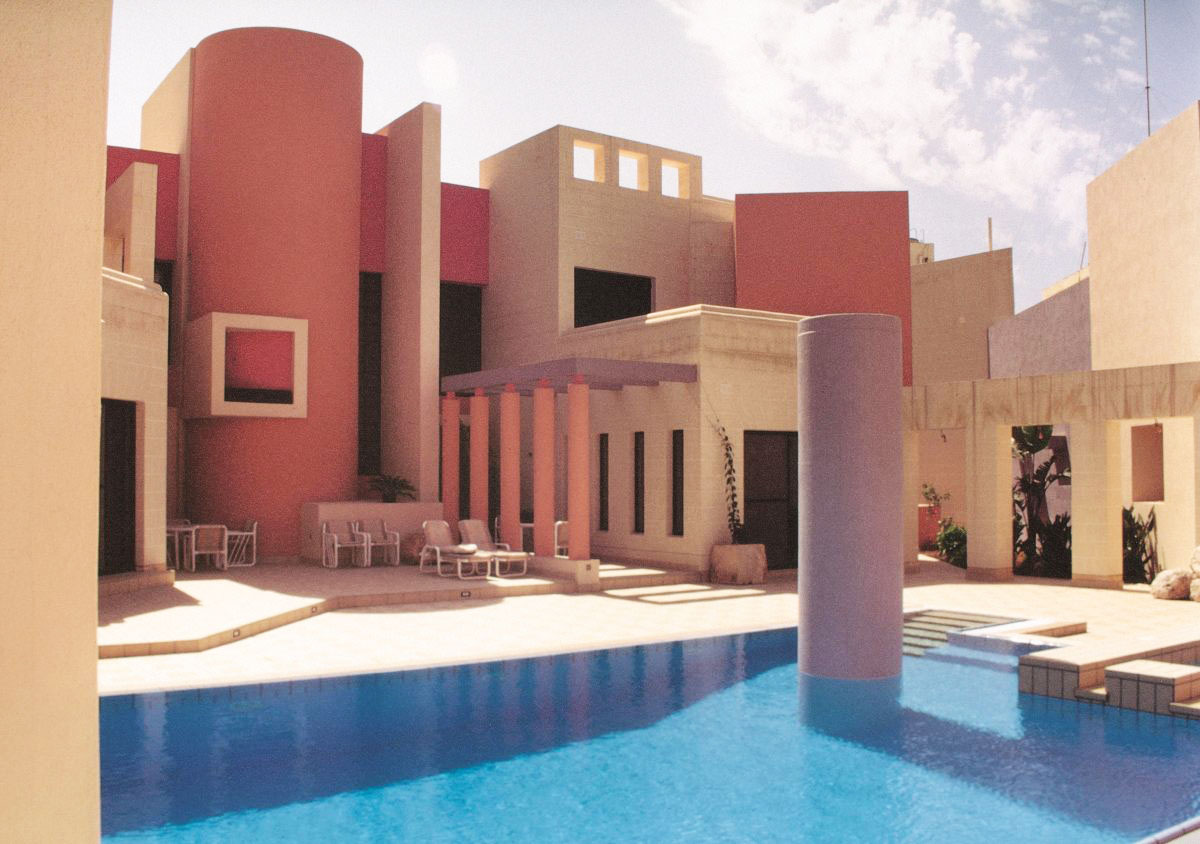

A Garden For Myriam – St Julians, Malta

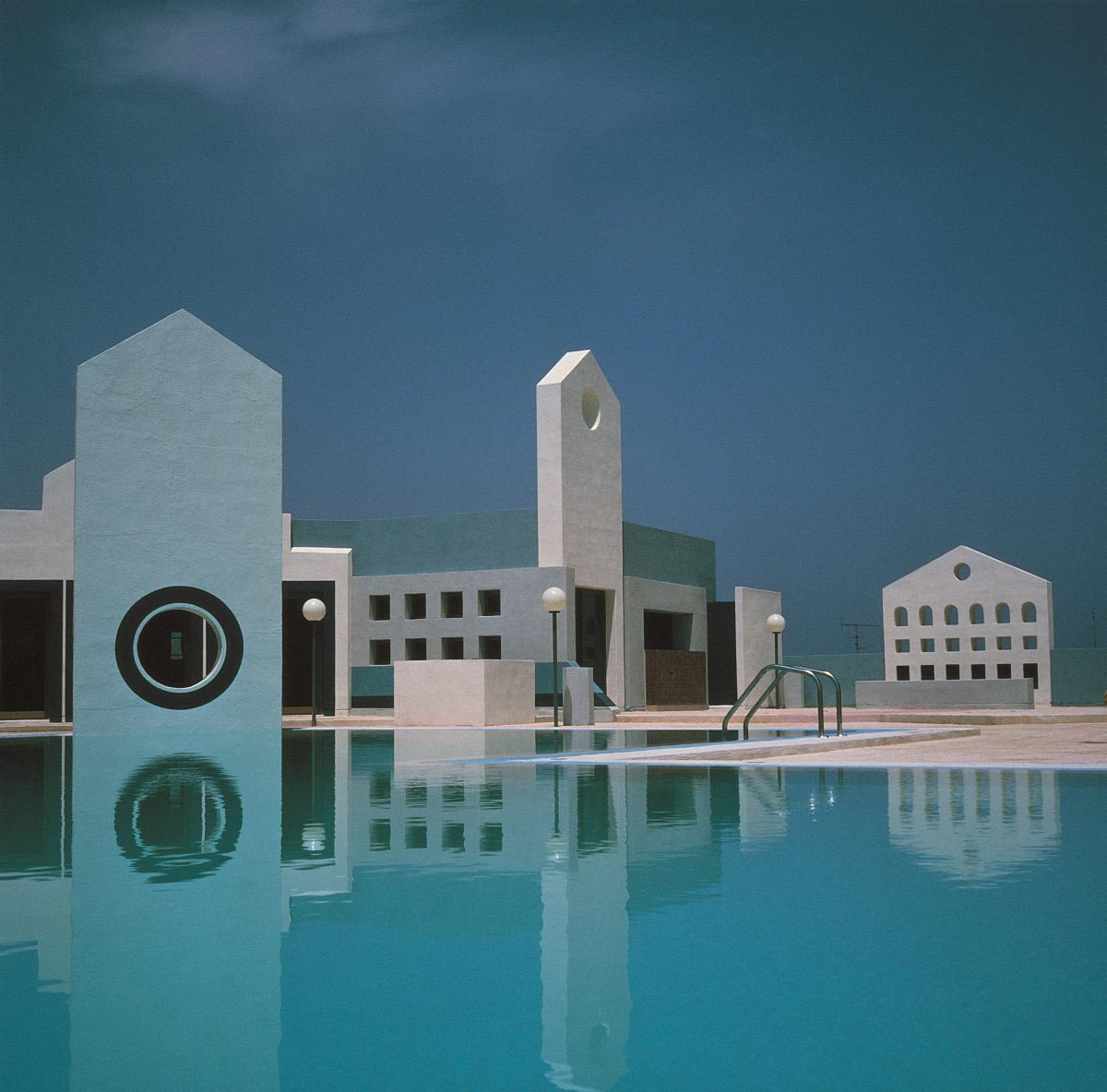

Aquasun Lido – St Julians, Malta

In stark contrast and to again manifest the power of architecture is the penchant which dictators throughout history had for architecture as a propaganda machine to promote their philosophy and ideology. Perhaps the most notorious example is the overstated, over-sized neoclassical architecture of the Third Reich conceived by Hitler and architect Albert Speer to promote the values of the Nazi party; architecture utilised strictly as propaganda.

In more recent times there have also been non-intentional examples of dysfunctional architecture, edifices which attracted apathy, crime and vandalism to such an extent that the buildings had to be abandoned and eventually demolished. The 1956 Pruitt-Igoe apartments in St Louis USA, infamous for crime, decay and squalor, had to be eventually demolished. Demolition was also the fate of the 1959 Hutcheson town C and the Red Road Apartments in Glasgow Scotland. These Brutalist edifices proved so unpopular with their tenants that they were soon scheduled for demolition. Both buildings are clear examples of how architecture can affect its users negatively.

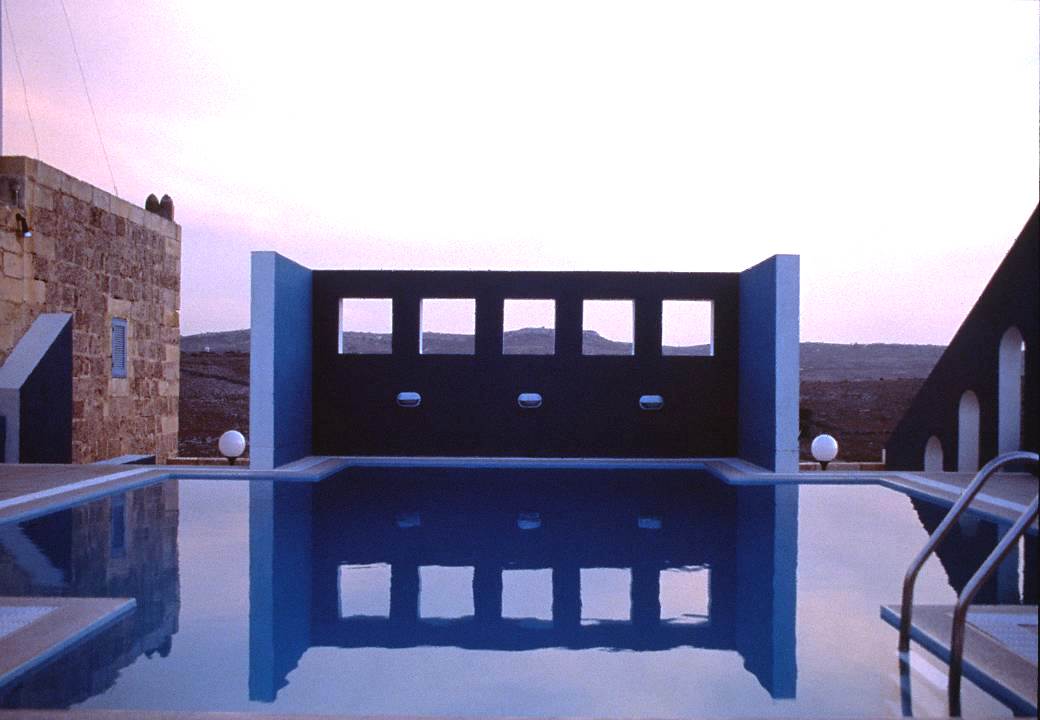

Ir-Razzett Ta’ Sandrina - Mgarr, Malta

Ir-Razzett Ta’ Sandrina - Mgarr, Malta

Dar Il-Hanin Samaritan – Santa Venera, Malta

Dar Il-Hanin Samaritan – Santa Venera, Malta

In today’s secular world architecture seems to focus more on monetary gain and profit; hence the endless soulless world-wide “dystopias”; the result of an age where we know the price of everything and the value of nothing. As Richard Rogers has said “today form follows profit”.

There is however, one area where particular attention is given to design quality and emotional response, and that is in the planning of hospital and healing environments. It is now recognised that well designed wards in hospitals contribute positively to patients’ healing process, as these spaces influence patients’ senses and their bodies consequently react and respond positively. Florence Nightingale long ago had already emphasised the need of “visual stimulation, interaction with nature and the use of colour” (it is well-known that colour itself is mood manipulative; hence strident reds and yellows for fast food outlets and more comforting blues and greens for relaxing venues).

Dar Il-Hanin Samaritan – Santa Venera, Malta

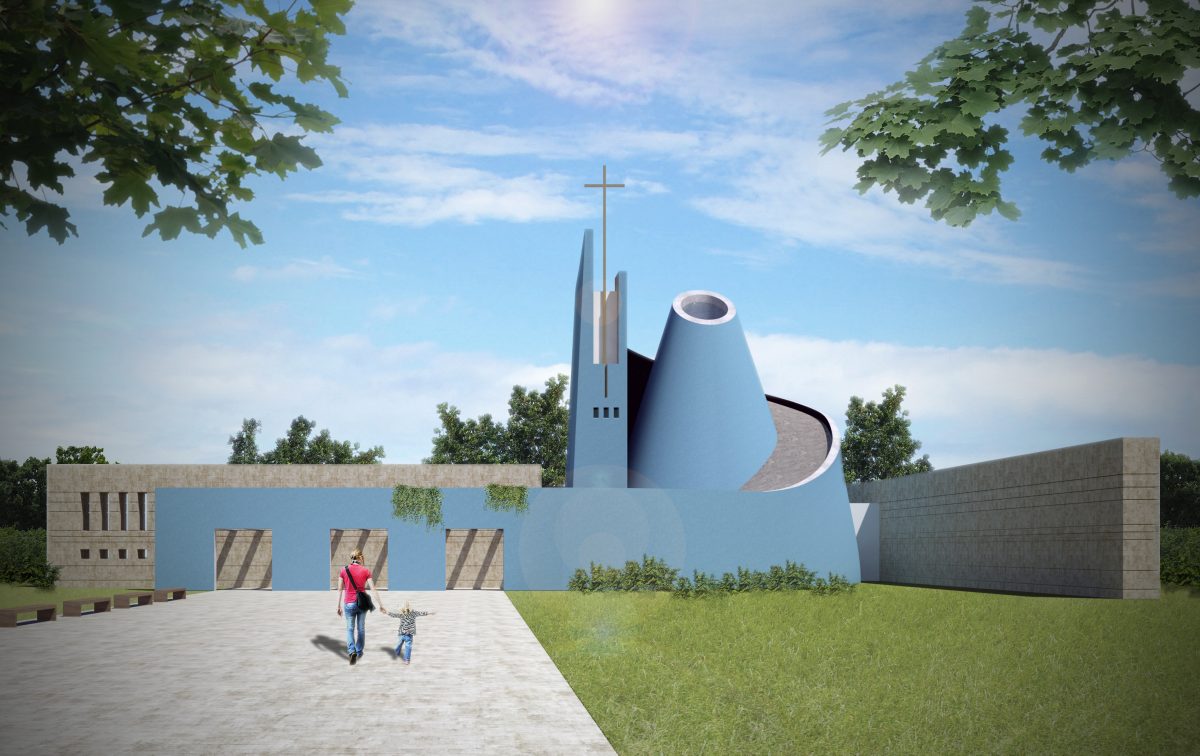

Manikata Church, Malta

Filfla Chapel, Malta

Chapel of the Rainbow, Malta

The most outstanding examples of contemporary user friendly medical edifices are the numerous Maggie Centres constructed over the last two or three decades in the United Kingdom and elsewhere. These are care homes specifically designed to respect and comfort cancer patients. Originally conceived by Maggie Keswick, herself a cancer victim and a believer in “the ability of buildings to affect people’s lives”, the Centres, after her demise are now nurtured by her husband, the distinguished architectural critic Charles Jencks. Through Jencks’ contacts with leading world architects, a number of excellently designed small-scale, patient friendly centres by such architects as Frank Gehry, Richard Rogers, Norman Foster, Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid and others have been built. The projects are veritable examples of how buildings can impart positive, emotional and friendly atmospheres to their users.

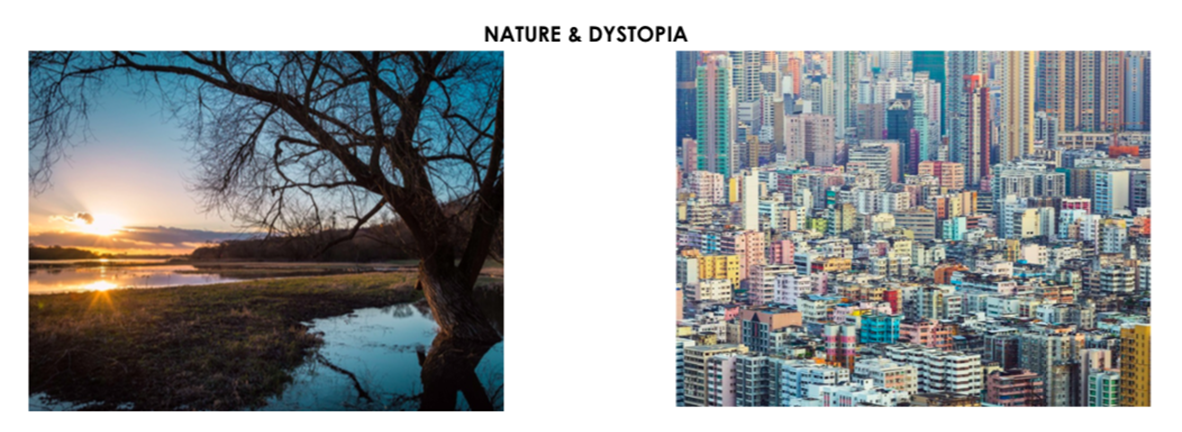

We all know that we react positively to nature. Its soothing sights, seas, lakes, woods and parks confer on us beneficial and salutary affects. On the other hand, we are unsettled and disturbed by the chaos and clutter of contemporary cities and our turbulent, breathless lifestyle. Urban chaos and the frenzied assault of technological gadgets, have depressing and disorientating effects on our lives. We live in a spiritually and morally barren age and architecture today seems to have abandoned its social and cultural mission to build a better and harmonious world, which is why the public at large seems to have fallen out of love with architecture. Architecture, once a route to enlightenment, has degenerated into a road to speculation. However, it still remains the architect’s solemn duty to create, not only shelters for the body, but more so homes for the soul, for as Axel Munthe reminds us “the soul needs more space than the body”.

San Raffaele Hospital Church, Malta

Avenue Of Hope, Malta

On my part, throughout my architectural career I have attempted to create an architecture of enchantment; an architecture of dreamscapes which gives poetry to the pragmatic, an architecture which arises not only from utility and practicality, but more so from the desire to sensualise and poeticise the human condition; an architecture of myth and magic which enriches the spirit and enhances the soul. Tennessee Williams’ words "I don’t want reality I want magic" and Jorge Luis Borges’ "my business is to weave dreams” together with Louis Kahn’s statement that "joy is the key word" best define my design philosophy. I believe in an architecture which relates to place and its memories, the zeitgeist of the age and one which enhances and augments the human spirit.

In the making of sacral spaces, the most difficult task for an architect, as confirmed by Antonio Gaudi who said that "the most arduous task for an architect is the design of a church”. One has the difficult task of measuring against the immeasurable. My search in the creation of sacral enclaves is for a sacred choreography mantled over by a rich chromatic palette to create ambiances of sacral mysticism. Yet, to achieve this, one needs not only all of one’s professional qualities but also an overlay of love, dedication and faith. It was my mentor Gio Ponti who told me that “religious architecture is not a question of architecture but one of religion". The words of C.S. Lewis "while others where building ships in their bottles, I was building a lighthouse", reflect my intentions in the making of the many edifices of sacrality I have been privileged to be involved with.

A Garden For Myriam – St Julians, Malta

We have seen that the human body is in fact a medium for our surrounding world and that our senses act as gateways to our mind, also that architecture is the stage-set on which man unfolds the drama of his life. Therefore, an architecture of beauty and harmony is conducive to a more favourable lifestyle. Nietzsche was right when he said that "architecture is an oratory of power through form” as was also Winston Churchill who said "we shape our buildings, thereafter they shape us”. Jung, the founder of analytical psychology correctly reminded us that "people are products of their physical environments”, and the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges was also correct when he stated that "it is more important to feel a place than to see it”.

"Places matter …they map our lives" - Rebecca Solnit.

Richard England was born in Malta and graduated in Architecture at the University of Malta continuing his studies in Italy at the Milan Polytechnic and also worked as a student - architect in the studio of the Italian architect-designer Gio Ponti. He is also a sculptor, photographer, poet, artist and the author of several books. His architectural works have been published in leading international journals. Richard England is a Visiting Professor at the University of Malta, having acted as Dean of the Faculty of Architecture between 1987 and 1989.

His buildings and designs have earned him numerous awards, including ten International Academy of Architecture Awards and two Commonwealth Association of Architects Regional awards. He was also awarded the Grand Prix of the International Academy of Architecture in 2006 and 2015 and the 2012 International Academy of Architecture Annual Award. In 2016 he was one of the winners of the European Architectural Awards. Richard England has lectured and worked in the following countries: USA, UK, Ex-Yugoslavia, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Italy, Argentina, Poland, Bulgaria, Russia, Kazakhstan and his native Malta.

Recently, Richard England has reviewed the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale with in-depth analyses and observations. Read England's exclusive article on here.

Top image: Private Villa - Siggiewi.

All images courtesy of Richard England, unless otherwise stated.