Submitted by WA Contents

Chinthaka Wickramage Associates built Pagoda House with protruding facade in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Architecture News - Jan 06, 2020 - 13:58 16763 views

Sri Lanka-based architecture firm Chinthaka Wickramage Associates has built a house that features protruding volumes for its facade in Sri Lanka.

Named Pagoda House, the project is located on a suburbia site, Nugegoda, which was as typical: a street with a rhythm of roof tiled, plastered brick boxes built to the limit of the road setbacks.

As the architects explain, site is bounded by existing houses on two sides with a main neighbourhood street on east side. The density and potential proximity of neighbouring houses was an issue to address. In a neighbourhood of older detached houses ranging from one to two storeys the narrative of the house began as a shell for a tall living room.

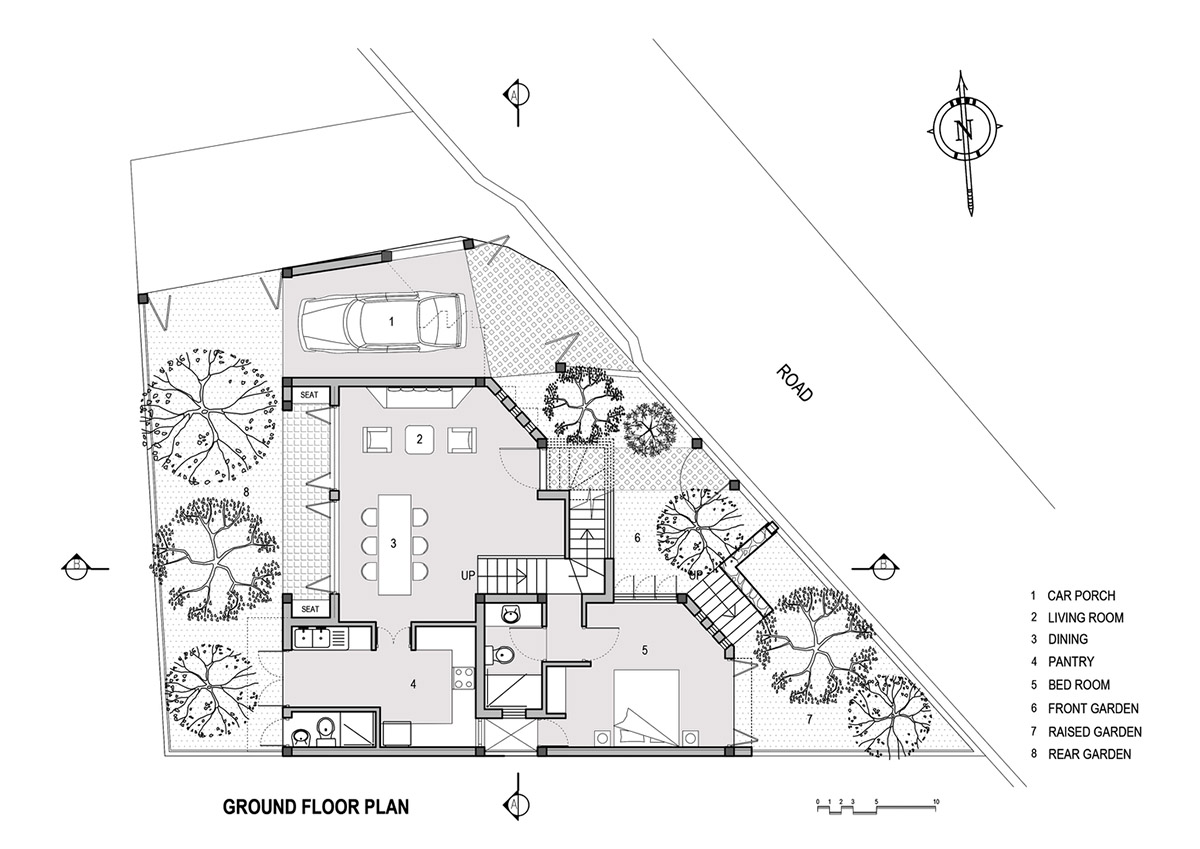

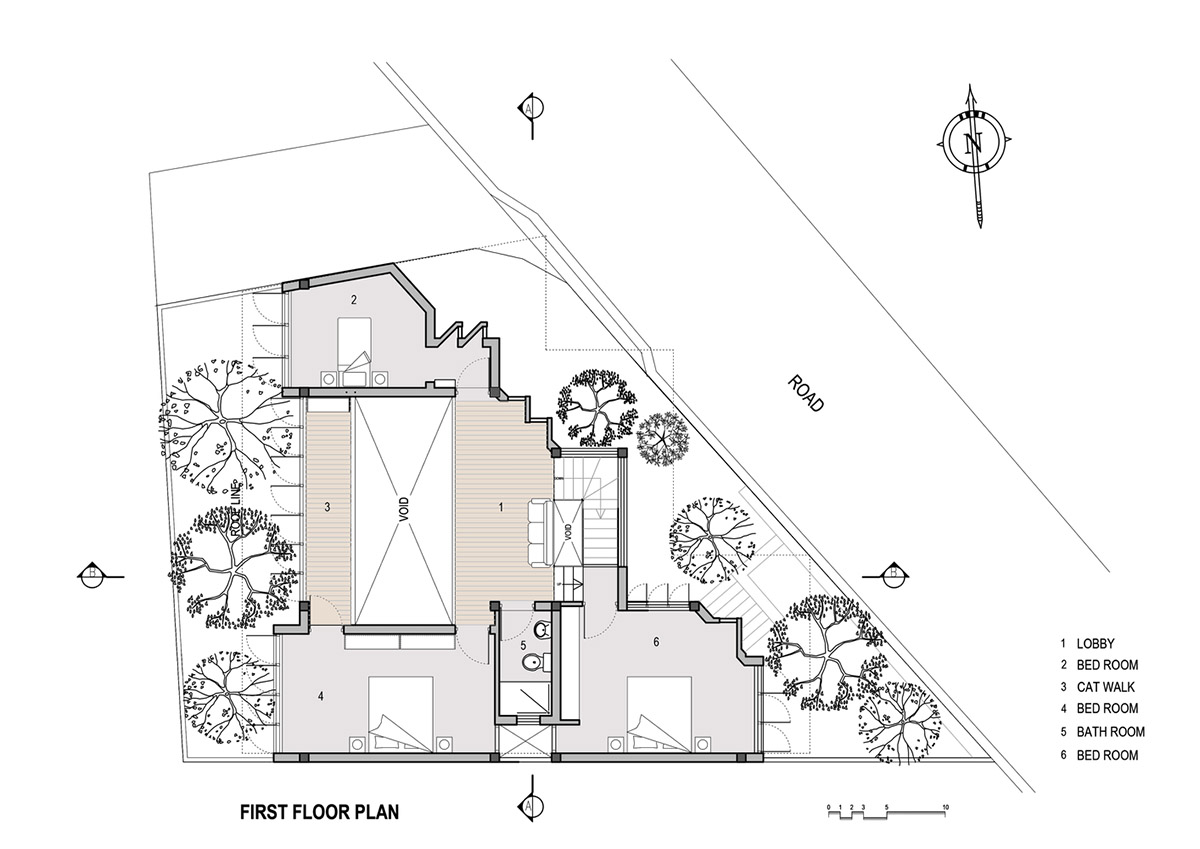

The four-bedroom house wraps its transparent inner spaces with a shell of un-plastered cement brick set into the frame of a raw concrete structure. The rear of the house contains the living dining room and kitchen on the ground floor, with bedrooms above. The Living & Dining areas look into the rear garden from the west, with the guest room on the opposite side.

"This house is an attempt to construct a house using cement bricks, a material newly introduced to the Sri Lankan market, which was expected to give a ‘unique character’ to the house and a 'counterpoint' to otherwise differently colour houses lining the neighbourhood," said Chinthaka Wickramage Associates.

"It was intended to be a discreet 'invisible' house with a neutral background."

The use of mono pitched single sloping zinc aluminium roof follow the road contours. Employment of double height space in the living room was meant to visually and physically link the two levels of this small house.

Planting of eight numbers root-ball replanted fruit bearing trees, in both front and rear gardens of the house, was meant to induce urban wildlife into the surroundings of the house, in an otherwise high density Colombo suburb of Nugegoda.

Use of cantilevered staircase under which, a visitor to the house access the main door, and the use of triangular cantilevered glass louver windows mimicking the trapezium shaped land shape are special features of the house. Incorporation of cantilevering triangular windows have given a certain 'machine like' external appearance to the house, in keeping with the famous architectural idiom 'House is a machine to live in'.

The architects' material selection is based on the lower cost of materials, much less in the way of products specifically manufactured to resist change and wear, than those which evolve best with weather and through time, finding new life in the manner of their assembly within the less than perfect construction culture which typifies Sri Lanka.

In retrospect, the simple cement brick wall formed a basic part of the glue concerning architectural economy as a philosophical basis. What made it so relevant with its application; however was its ability to age well.

Aluminium, glass, concrete and cement bricks, form the palette of finishes intended to bring that tactile quality to a freshly built house. Cement brick selection and editing of details do effect conceptual continuity and aesthetic cohesion to some degree of cost consciousness.

The need for construction simplicity and the power of exposed brick with tight budgets began the narrative of architectural economy. In summary Pagoda house is designed as an environment of basic solids and voids, given ‘form’ through controlled assembly of cement bricks, concrete, aluminium and glass.

Pagoda House is inspired on the concepts of incompleteness & shock contrast and relies on the paradigm of textural contrast. The contrast of the entire house of cement bricks with the crispness of glass, aluminium frames and cleanly painted ceilings. The house attempts at design of cross ventilation and naturally lit space in a residential context and the maximisation of usable area for added value.

For the kind of ‘rawness’ which was envisioned the principals of detail management became a challenge: a simple and effective way of maintaining construction economy. The structural order of the house was designed to serve the purposes of finish with its enclosure, the result of balance found through tonal homogeneity.

The idea of a buildings ‘envelop’ being captured as part of its architecture had always felt more relevant from the view of construction economy and final aesthetics, and it was carried out to a reasonable effect.

The narrative made distinctions between the textural and spatial qualities of each natural or constructed element in context. This complicity engages in the intelligent search for greater economy of means, a part of the entire process which has the product of work develop its ‘under-constructed’ and less polished sense of finish. The thinking and making of architecture as it engages the specific context of its location are the formal elements of inquiry with regard to this work.

Specific context also applies to the way any one country or construction region most commonly works and builds, about which materials and processes have best adopted functionally and economically over time in each of their specific locations. For the diligent architect, context will include budget constraints and relevance of use.

Pagoda House is also about how specificity of place can guide the processes and subsequent ‘form’ of relevant design. The house is intended to age with time and to receive the colour and life of dwelling within, its architecture hidden, for the most part, by the foliage of its very first room, the front garden.

Whereas spatial value has been more commonly understood to be derived from the light and its revealing of ‘tactile quality’, the design explorations of the Pagoda House, having prioritized the details of function equally with that of space making, have found subtler working details to contribute as much as, and possibly more, to perceived ‘spatial quality’.

In summary pagoda House is a project laced with details testing rawness, un-refinement and the unfinished. Lessons learned from the project widened and reinforced our growing understanding of how materials give texture and age gracefully in monsoon Asia. The house became a careful balance of grey, black, white, concrete and age.

Finally with all the requirements of natural ventilation, functionality and construction economy in mind the house was designed to be predominantly self-maintaining and aesthetically elegant as it weathered the grace of tropical humidity.

Pagoda House was the first of its type which formally began to maximise the trades and the materials of a local building industry, minimising cost through low cost production means; its methods beginning to show consistency with the philosophical leanings of ‘texture’ through economy.

Ground floor plan

First floor plan

All images © Kesara Ratnavibhushana Photography