World Architecture Awards 10+5+X Submissions

World Architecture Awards Submissions / 53rd Cycle

Vote button will be active when the World Architecture Community officially announces the Voting period on the website and emails. Please use this and the following pages to Vote if you are a signed-in registered member of the World Architecture Community and feel free to Vote for as many projects as you wish.

How to participate

WA Awards Submissions

WA Awards Winners

Architectural Projects Interior Design Projects

Architectural Projects Interior Design Projects

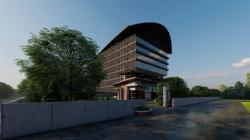

Conceptual Planning Scheme for Chongqing University's Wisdom Valley Campus

As the new campus for one of the best universities in Western China, designed to accommodate 10,000 faculty and students in the future, the primary design goal for the Chongqing University Wisdom Valley Campus is to create a future campus that integrates nature, ecology, education, technology, and innovation. Concurrently, the campus is intended to serve as a vital, organic component of the Chongqing Science City, a major new science and technology hub in Western China.

The project site reflects the natural geographical characteristics of Chongqing, the world-renowned mountain metropolis: the environment of coexisting mountains and water fostered the development of this site. Jinyun Mountain on the west side serves as the backdrop for the campus with its continuous mountain ranges. The confluence of the Huxi River and Yangjiagou Stream forms a natural peninsula known as Qinglongzui.

The master plan is dedicated to transforming the conventional closed university campus model. The university of the future belongs not only to its faculty and students but also to the city. The campus layout, characterized by a well-balanced mix of density and open, grand gestures, creates an open space facing the city in the pre-campus area on the east side, forming a massive C-shaped "Academic Loop." This loop connects the various campus zones while actively engaging the city, promoting interaction and co-existence.

Under the principle of "Design Following Nature," the naturally formed confluence of the two rivers within the campus is enlarged into an ecological peninsula. This peninsula is designated as the Campus Energetic Core(CEC), housing landmark buildings such as key laboratories, the library, and the auditorium. Together with natural elements like the lake, sparse woods, and lawns, they form the ecological heart of the campus.

The design creates a campus spatial model that breaks down disciplinary barriers. The Academic Loop consists of a series of public classrooms and laboratories, offering high efficiency and intensive use. Faculty and students from colleges such as Optoelectronic Engineering, Microelectronics and Communication Engineering, and Intelligent Connected Vehicles will study here, promoting disciplinary integration and cross-disciplinary research.

Furthermore, the Academic Loop is also a Three-Dimensional Efficiency Ring. By scientifically utilizing the elevation differences through a three-dimensional integrated transportation strategy, it connects three distinct spatial layers: the underground vehicular flow, the ground-level pedestrian flow, and the overhead academic public platform.

The longitudinal campus public space running north-south through the campus forms two major campus composite axes, linking teaching and research, health and sports, and residential living. The Waterfront Public Vitality Belt on the south shapes both banks of the Huxi River into a water-friendly social interaction space. The research and office buildings on the east bank adopt a modular spatial model to meet flexible development needs. The Northern Campus Boulevard carries the campus's century-long history, incorporating cultural landscapes to organically integrate culture and history with the modern campus space.

Site Area: 5,900,000㎡ (39.3 hectares)

Construction Gross Area: 465,000㎡

Chu Donozhu, Yang Yang, Chu Longfei, Guan Shihan, Yang Yue, Yu Yan, Zheng wenchong, Deng Yuwen, Liu Xueyang, Zhou lingzhi, Shen Qingzhi, Li Baopeng, Zhang Songming, Wang Dagang

The project site reflects the natural geographical characteristics of Chongqing, the world-renowned mountain metropolis: the environment of coexisting mountains and water fostered the development of this site. Jinyun Mountain on the west side serves as the backdrop for the campus with its continuous mountain ranges. The confluence of the Huxi River and Yangjiagou Stream forms a natural peninsula known as Qinglongzui.

The master plan is dedicated to transforming the conventional closed university campus model. The university of the future belongs not only to its faculty and students but also to the city. The campus layout, characterized by a well-balanced mix of density and open, grand gestures, creates an open space facing the city in the pre-campus area on the east side, forming a massive C-shaped "Academic Loop." This loop connects the various campus zones while actively engaging the city, promoting interaction and co-existence.

Under the principle of "Design Following Nature," the naturally formed confluence of the two rivers within the campus is enlarged into an ecological peninsula. This peninsula is designated as the Campus Energetic Core(CEC), housing landmark buildings such as key laboratories, the library, and the auditorium. Together with natural elements like the lake, sparse woods, and lawns, they form the ecological heart of the campus.

The design creates a campus spatial model that breaks down disciplinary barriers. The Academic Loop consists of a series of public classrooms and laboratories, offering high efficiency and intensive use. Faculty and students from colleges such as Optoelectronic Engineering, Microelectronics and Communication Engineering, and Intelligent Connected Vehicles will study here, promoting disciplinary integration and cross-disciplinary research.

Furthermore, the Academic Loop is also a Three-Dimensional Efficiency Ring. By scientifically utilizing the elevation differences through a three-dimensional integrated transportation strategy, it connects three distinct spatial layers: the underground vehicular flow, the ground-level pedestrian flow, and the overhead academic public platform.

The longitudinal campus public space running north-south through the campus forms two major campus composite axes, linking teaching and research, health and sports, and residential living. The Waterfront Public Vitality Belt on the south shapes both banks of the Huxi River into a water-friendly social interaction space. The research and office buildings on the east bank adopt a modular spatial model to meet flexible development needs. The Northern Campus Boulevard carries the campus's century-long history, incorporating cultural landscapes to organically integrate culture and history with the modern campus space.

Site Area: 5,900,000㎡ (39.3 hectares)

Construction Gross Area: 465,000㎡

Chu Donozhu, Yang Yang, Chu Longfei, Guan Shihan, Yang Yue, Yu Yan, Zheng wenchong, Deng Yuwen, Liu Xueyang, Zhou lingzhi, Shen Qingzhi, Li Baopeng, Zhang Songming, Wang Dagang

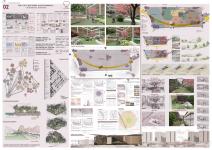

Rural Learning House

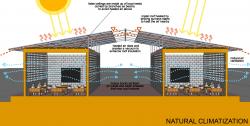

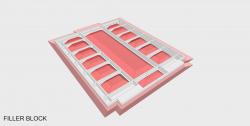

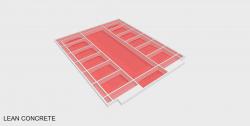

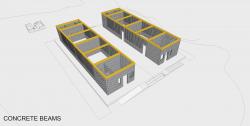

The project is designed for students to study in rural areas, villages and mountains where there is no school. In these rural areas where there are very few households outside the city, there is often no school structure for education. Even the smallest school structures in existing cities remain very large compared to the population in these rural areas. For this reason, these learning houses & schools have been designed with a minimum budget so that children living in rural areas and growing up here have at least an educational structure.In the project, it is aimed to be built with local materials without using any external materials. In this frame, the single-storey building consists of a block wall and a reinforced concrete beam to be placed on it. The roof structure that will come on the reinforced concrete beam will protect the structure from the excessive heat of the sun.The structure, which consists of 2 blocks and 4 classrooms, connects it with the roof. For natural ventilation, gaps were created with bricks on the wall of the building. The sustainability of education will be ensured by the expansion of education venues in rural areas, which will be built with this minimum budget.2 water tanks in the building will be used to meet the water needs of the building. A water well is also considered on the side of the building to use the natural underground water.Small gaps repeated on both walls of each block of the building also contribute to clean ventilation and cooling by passing through the building without the wind hitting the building. In this respect, these small spaces not only provide natural light intake, but also create natural cooling. With this aspect, the building was designed with a completely sustainable architecture.

Block wall structure

Selim Senin

Block wall structure

Selim Senin

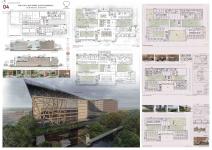

Hefei Nanmen Primary School Yingzhou Campus

The project is located in the Southern New District of Fuyang City and will be named Qinghe Road First Primary School upon completion. It primarily consists of an underground parking garage, teaching buildings, a cafeteria, an indoor sports ground, and an administrative office building. Leveraging the orientation characteristics of the site, the design adopts a regular, compact, and highly efficient layout. By making full use of the site's depth, the internal building spacing is appropriately expanded to ensure the teaching buildings receive ample sunlight. Additionally, the teaching area, sports area, and living area are clearly defined.

The E-shaped layout facing the interior of the school forms two large semi-enclosed courtyards, creating a courtyard-style environment. Meanwhile, the eastern corridor presents a continuous urban facade along the city road. The school's southern entrance plaza faces the main city road, serving as the primary gathering area for parents dropping off and picking up their children. This design also provides an effective buffer to the city's main road, while a secondary entrance is set up on the eastern side. The two inner courtyards face the sports field and, together with the main landscape axis of the southern entrance, form recreational spaces for students, creating a comfortable, relaxed, and pleasant campus environment.

The architectural design features a light gray color scheme as the main tone, complemented by sections of dark gray walls and dark gray air conditioning louvers. Accents of colorful components are appropriately incorporated to create a lively and elegant architectural style. The four courtyards on the eastern side are enhanced with vibrant color accents, forming engaging learning and activity corners.

Location: China, Fuyang

Area:20000 sqm

Far:0.4

Client: Fuyang Education Bureau

Hongkai Li, Ya Yang, Jiachen Fei, Boyan Chen, Songtian Zhang, Qinlin Qin, Yuanhang Wang, Chunyang Ma

The E-shaped layout facing the interior of the school forms two large semi-enclosed courtyards, creating a courtyard-style environment. Meanwhile, the eastern corridor presents a continuous urban facade along the city road. The school's southern entrance plaza faces the main city road, serving as the primary gathering area for parents dropping off and picking up their children. This design also provides an effective buffer to the city's main road, while a secondary entrance is set up on the eastern side. The two inner courtyards face the sports field and, together with the main landscape axis of the southern entrance, form recreational spaces for students, creating a comfortable, relaxed, and pleasant campus environment.

The architectural design features a light gray color scheme as the main tone, complemented by sections of dark gray walls and dark gray air conditioning louvers. Accents of colorful components are appropriately incorporated to create a lively and elegant architectural style. The four courtyards on the eastern side are enhanced with vibrant color accents, forming engaging learning and activity corners.

Location: China, Fuyang

Area:20000 sqm

Far:0.4

Client: Fuyang Education Bureau

Hongkai Li, Ya Yang, Jiachen Fei, Boyan Chen, Songtian Zhang, Qinlin Qin, Yuanhang Wang, Chunyang Ma

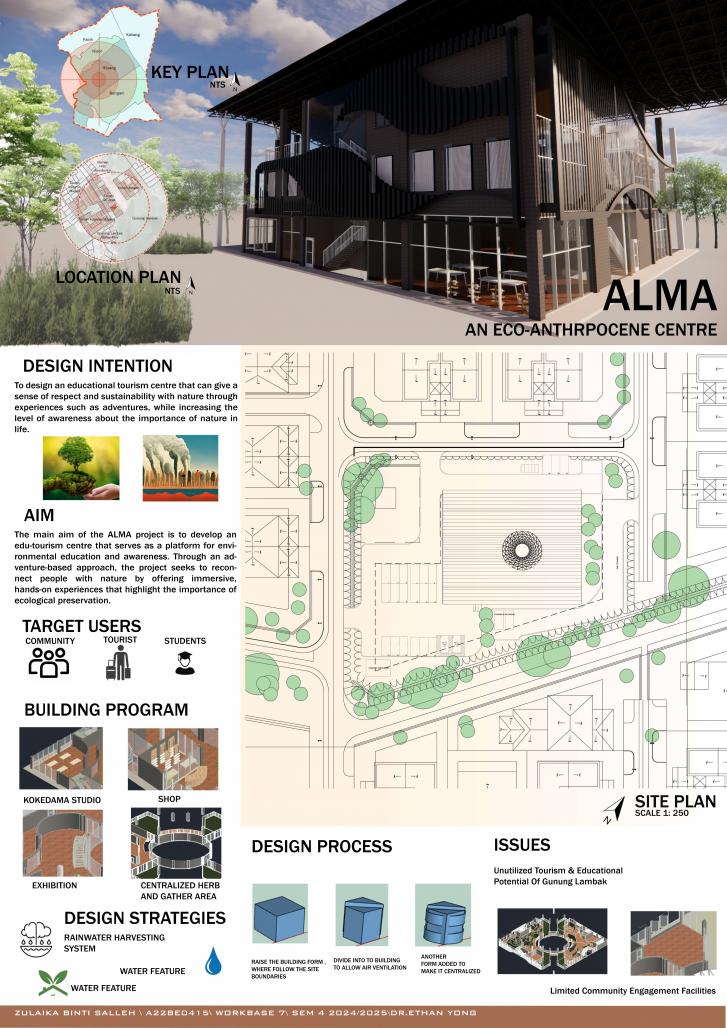

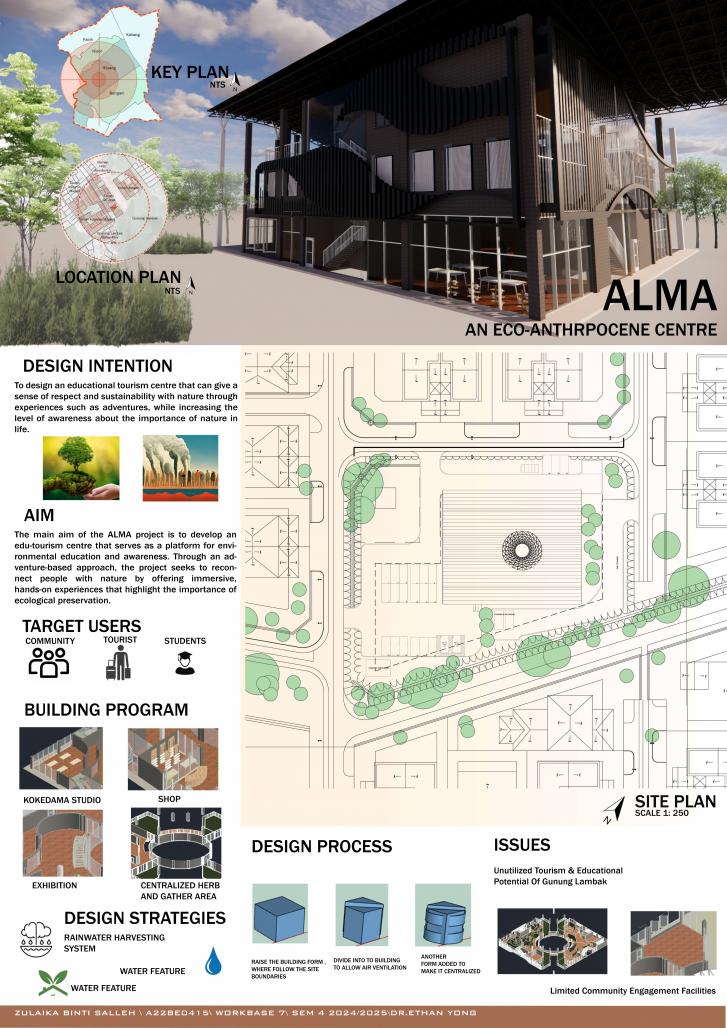

ALMA

DESIGN STATEMENT

The ALMA: Eco-Anthropocene Centre is envisioned as a catalyst for environmental awareness and sustainable education situated within the ecological and cultural context of Gunung Lambak, Johor. The project addresses the site’s underutilised tourism and educational potential by introducing an interactive eco-education hub that redefines the relationship between human activity and the natural ecosystem. ALMA aims to bridge people and nature through an experiential learning environment that promotes empathy, stewardship, and ecological consciousness.

At the conceptual level, the project is grounded in the eco-anthropocentric approach, which emphasises the coexistence between humanity and the environment. Rather than treating nature as a passive backdrop, the design positions it as an active agent shaping spatial experience and environmental performance. Architecture, therefore, becomes a mediator between built and natural systems, creating a balance that sustains both.

The main objective of the ALMA project is to create a space that serves as both an educational and tourist landmark, highlighting the importance of ecological preservation while enhancing community engagement. It seeks to transform awareness into participation and participation into change by offering immersive hands-on experiences that connect visitors directly to natural processes. Through workshops, exhibitions and learning activities, users are invited to reflect on their role within the environment and the impact of their daily choices on the planet.

The design concept evolves from a contextual and responsive understanding of the site. Gunung Lambak’s lush vegetation, undulating terrain and existing circulation patterns guided the formation of the built form. The architecture is raised slightly above ground to maintain natural drainage, reduce disruption to the ecosystem and enhance ventilation. This elevated form also allows for visual continuity between indoor and outdoor spaces, promoting a seamless interaction between built and natural realms.

The design process began by mapping the site’s environmental and social characteristics. The form was shaped to follow site boundaries, then divided into volumes to increase air permeability and daylight penetration. A central courtyard was introduced to function as a gathering and exhibition space surrounded by circulation corridors that promote passive cooling. Additional layers of vegetation and water features were integrated to moderate the microclimate and enhance the sensory experience.

Environmental sustainability forms the backbone of the design strategy. Systems such as rainwater harvesting, natural ventilation and daylighting are incorporated to reduce dependence on mechanical energy. A water feature integrated into the landscape reinforces the idea of cyclical resource use while also providing a calming and reflective experience for visitors. The design prioritises passive solutions before introducing active systems, ensuring minimal energy consumption and long-term resilience.

Programmatically, the centre consists of four main components: the kokedama studio, exhibition gallery, retail, cafe, centralised herb and gathering area. Each program is strategically positioned to facilitate a journey of exploration and learning. The Exhibition Gallery provides a platform for environmental displays and community workshops, while the kokedama studio allows visitors to engage in hands-on plant-based crafts that symbolise life and renewal. The retail and cafe areas support local products and artisans, fostering an economy that aligns with sustainability values.

Material selection emphasises locality and tactility. The use of timber, bamboo and natural stone reduces embodied carbon while blending harmoniously with the surrounding landscape. The natural tones and textures create a warm, biophilic atmosphere that encourages users to feel grounded and connected to the environment. Transparency in façade treatment enhances visibility and interaction, reinforcing the idea of openness and coexistence.

From a social and cultural perspective, the ALMA Centre acts as a platform for community engagement and knowledge exchange. Gunung Lambak currently functions primarily as a recreational destination. This project repositions it as an educational landscape that invites students, tourists, and residents to participate in sustainability learning. The inclusion of public spaces and communal programs strengthens local identity while promoting environmental literacy across different age groups.

Addressing the issues of limited tourism utilisation and lack of educational facilities, the project revitalises the site through an architectural intervention that merges environmental, social and economic sustainability. By activating an overlooked site into a vibrant eco-learning hub, ALMA contributes to the broader goal of sustainable urban and rural development in Malaysia.

Ultimately, the ALMA: Eco-Anthropocene Centre represents a vision for architecture that is both reflective and proactive, a built form that teaches, heals and inspires. It demonstrates how design can move beyond aesthetics to become a medium for education, empathy and environmental stewardship. The project aspires to become a model for sustainable tourism architecture where learning and leisure coexist harmoniously within the natural world.

Through its integration of ecological systems, community participation and educational programming, ALMA embodies the essence of the Anthropocene, acknowledging human impact on the planet while striving to restore balance through awareness and action. It is not merely a building, but a living narrative of coexistence, reminding us that sustainability begins with connection and connection begins with design.

DESIGN STATEMENT

The ALMA: Eco-Anthropocene Centre is envisioned as a catalyst for environmental awareness and sustainable education situated within the ecological and cultural context of Gunung Lambak, Johor. The project addresses the site’s underutilised tourism and educational potential by introducing an interactive eco-education hub that redefines the relationship between human activity and the natural ecosystem. ALMA aims to bridge people and nature through an experiential learning environment that promotes empathy, stewardship, and ecological consciousness.

At the conceptual level, the project is grounded in the eco-anthropocentric approach, which emphasises the coexistence between humanity and the environment. Rather than treating nature as a passive backdrop, the design positions it as an active agent shaping spatial experience and environmental performance. Architecture, therefore, becomes a mediator between built and natural systems, creating a balance that sustains both.

The main objective of the ALMA project is to create a space that serves as both an educational and tourist landmark, highlighting the importance of ecological preservation while enhancing community engagement. It seeks to transform awareness into participation and participation into change by offering immersive hands-on experiences that connect visitors directly to natural processes. Through workshops, exhibitions and learning activities, users are invited to reflect on their role within the environment and the impact of their daily choices on the planet.

The design concept evolves from a contextual and responsive understanding of the site. Gunung Lambak’s lush vegetation, undulating terrain and existing circulation patterns guided the formation of the built form. The architecture is raised slightly above ground to maintain natural drainage, reduce disruption to the ecosystem and enhance ventilation. This elevated form also allows for visual continuity between indoor and outdoor spaces, promoting a seamless interaction between built and natural realms.

The design process began by mapping the site’s environmental and social characteristics. The form was shaped to follow site boundaries, then divided into volumes to increase air permeability and daylight penetration. A central courtyard was introduced to function as a gathering and exhibition space surrounded by circulation corridors that promote passive cooling. Additional layers of vegetation and water features were integrated to moderate the microclimate and enhance the sensory experience.

Environmental sustainability forms the backbone of the design strategy. Systems such as rainwater harvesting, natural ventilation and daylighting are incorporated to reduce dependence on mechanical energy. A water feature integrated into the landscape reinforces the idea of cyclical resource use while also providing a calming and reflective experience for visitors. The design prioritises passive solutions before introducing active systems, ensuring minimal energy consumption and long-term resilience.

Programmatically, the centre consists of four main components: the kokedama studio, exhibition gallery, retail, cafe, centralised herb and gathering area. Each program is strategically positioned to facilitate a journey of exploration and learning. The Exhibition Gallery provides a platform for environmental displays and community workshops, while the kokedama studio allows visitors to engage in hands-on plant-based crafts that symbolise life and renewal. The retail and cafe areas support local products and artisans, fostering an economy that aligns with sustainability values.

Material selection emphasises locality and tactility. The use of timber, bamboo and natural stone reduces embodied carbon while blending harmoniously with the surrounding landscape. The natural tones and textures create a warm, biophilic atmosphere that encourages users to feel grounded and connected to the environment. Transparency in façade treatment enhances visibility and interaction, reinforcing the idea of openness and coexistence.

From a social and cultural perspective, the ALMA Centre acts as a platform for community engagement and knowledge exchange. Gunung Lambak currently functions primarily as a recreational destination. This project repositions it as an educational landscape that invites students, tourists, and residents to participate in sustainability learning. The inclusion of public spaces and communal programs strengthens local identity while promoting environmental literacy across different age groups.

Addressing the issues of limited tourism utilisation and lack of educational facilities, the project revitalises the site through an architectural intervention that merges environmental, social and economic sustainability. By activating an overlooked site into a vibrant eco-learning hub, ALMA contributes to the broader goal of sustainable urban and rural development in Malaysia.

Ultimately, the ALMA: Eco-Anthropocene Centre represents a vision for architecture that is both reflective and proactive, a built form that teaches, heals and inspires. It demonstrates how design can move beyond aesthetics to become a medium for education, empathy and environmental stewardship. The project aspires to become a model for sustainable tourism architecture where learning and leisure coexist harmoniously within the natural world.

Through its integration of ecological systems, community participation and educational programming, ALMA embodies the essence of the Anthropocene, acknowledging human impact on the planet while striving to restore balance through awareness and action. It is not merely a building, but a living narrative of coexistence, reminding us that sustainability begins with connection and connection begins with design.

Designer: Zulaika Salleh

Supervisor (or Instructor): Dr Ethan Yong

The ALMA: Eco-Anthropocene Centre is envisioned as a catalyst for environmental awareness and sustainable education situated within the ecological and cultural context of Gunung Lambak, Johor. The project addresses the site’s underutilised tourism and educational potential by introducing an interactive eco-education hub that redefines the relationship between human activity and the natural ecosystem. ALMA aims to bridge people and nature through an experiential learning environment that promotes empathy, stewardship, and ecological consciousness.

At the conceptual level, the project is grounded in the eco-anthropocentric approach, which emphasises the coexistence between humanity and the environment. Rather than treating nature as a passive backdrop, the design positions it as an active agent shaping spatial experience and environmental performance. Architecture, therefore, becomes a mediator between built and natural systems, creating a balance that sustains both.

The main objective of the ALMA project is to create a space that serves as both an educational and tourist landmark, highlighting the importance of ecological preservation while enhancing community engagement. It seeks to transform awareness into participation and participation into change by offering immersive hands-on experiences that connect visitors directly to natural processes. Through workshops, exhibitions and learning activities, users are invited to reflect on their role within the environment and the impact of their daily choices on the planet.

The design concept evolves from a contextual and responsive understanding of the site. Gunung Lambak’s lush vegetation, undulating terrain and existing circulation patterns guided the formation of the built form. The architecture is raised slightly above ground to maintain natural drainage, reduce disruption to the ecosystem and enhance ventilation. This elevated form also allows for visual continuity between indoor and outdoor spaces, promoting a seamless interaction between built and natural realms.

The design process began by mapping the site’s environmental and social characteristics. The form was shaped to follow site boundaries, then divided into volumes to increase air permeability and daylight penetration. A central courtyard was introduced to function as a gathering and exhibition space surrounded by circulation corridors that promote passive cooling. Additional layers of vegetation and water features were integrated to moderate the microclimate and enhance the sensory experience.

Environmental sustainability forms the backbone of the design strategy. Systems such as rainwater harvesting, natural ventilation and daylighting are incorporated to reduce dependence on mechanical energy. A water feature integrated into the landscape reinforces the idea of cyclical resource use while also providing a calming and reflective experience for visitors. The design prioritises passive solutions before introducing active systems, ensuring minimal energy consumption and long-term resilience.

Programmatically, the centre consists of four main components: the kokedama studio, exhibition gallery, retail, cafe, centralised herb and gathering area. Each program is strategically positioned to facilitate a journey of exploration and learning. The Exhibition Gallery provides a platform for environmental displays and community workshops, while the kokedama studio allows visitors to engage in hands-on plant-based crafts that symbolise life and renewal. The retail and cafe areas support local products and artisans, fostering an economy that aligns with sustainability values.

Material selection emphasises locality and tactility. The use of timber, bamboo and natural stone reduces embodied carbon while blending harmoniously with the surrounding landscape. The natural tones and textures create a warm, biophilic atmosphere that encourages users to feel grounded and connected to the environment. Transparency in façade treatment enhances visibility and interaction, reinforcing the idea of openness and coexistence.

From a social and cultural perspective, the ALMA Centre acts as a platform for community engagement and knowledge exchange. Gunung Lambak currently functions primarily as a recreational destination. This project repositions it as an educational landscape that invites students, tourists, and residents to participate in sustainability learning. The inclusion of public spaces and communal programs strengthens local identity while promoting environmental literacy across different age groups.

Addressing the issues of limited tourism utilisation and lack of educational facilities, the project revitalises the site through an architectural intervention that merges environmental, social and economic sustainability. By activating an overlooked site into a vibrant eco-learning hub, ALMA contributes to the broader goal of sustainable urban and rural development in Malaysia.

Ultimately, the ALMA: Eco-Anthropocene Centre represents a vision for architecture that is both reflective and proactive, a built form that teaches, heals and inspires. It demonstrates how design can move beyond aesthetics to become a medium for education, empathy and environmental stewardship. The project aspires to become a model for sustainable tourism architecture where learning and leisure coexist harmoniously within the natural world.

Through its integration of ecological systems, community participation and educational programming, ALMA embodies the essence of the Anthropocene, acknowledging human impact on the planet while striving to restore balance through awareness and action. It is not merely a building, but a living narrative of coexistence, reminding us that sustainability begins with connection and connection begins with design.

DESIGN STATEMENT

The ALMA: Eco-Anthropocene Centre is envisioned as a catalyst for environmental awareness and sustainable education situated within the ecological and cultural context of Gunung Lambak, Johor. The project addresses the site’s underutilised tourism and educational potential by introducing an interactive eco-education hub that redefines the relationship between human activity and the natural ecosystem. ALMA aims to bridge people and nature through an experiential learning environment that promotes empathy, stewardship, and ecological consciousness.

At the conceptual level, the project is grounded in the eco-anthropocentric approach, which emphasises the coexistence between humanity and the environment. Rather than treating nature as a passive backdrop, the design positions it as an active agent shaping spatial experience and environmental performance. Architecture, therefore, becomes a mediator between built and natural systems, creating a balance that sustains both.

The main objective of the ALMA project is to create a space that serves as both an educational and tourist landmark, highlighting the importance of ecological preservation while enhancing community engagement. It seeks to transform awareness into participation and participation into change by offering immersive hands-on experiences that connect visitors directly to natural processes. Through workshops, exhibitions and learning activities, users are invited to reflect on their role within the environment and the impact of their daily choices on the planet.

The design concept evolves from a contextual and responsive understanding of the site. Gunung Lambak’s lush vegetation, undulating terrain and existing circulation patterns guided the formation of the built form. The architecture is raised slightly above ground to maintain natural drainage, reduce disruption to the ecosystem and enhance ventilation. This elevated form also allows for visual continuity between indoor and outdoor spaces, promoting a seamless interaction between built and natural realms.

The design process began by mapping the site’s environmental and social characteristics. The form was shaped to follow site boundaries, then divided into volumes to increase air permeability and daylight penetration. A central courtyard was introduced to function as a gathering and exhibition space surrounded by circulation corridors that promote passive cooling. Additional layers of vegetation and water features were integrated to moderate the microclimate and enhance the sensory experience.

Environmental sustainability forms the backbone of the design strategy. Systems such as rainwater harvesting, natural ventilation and daylighting are incorporated to reduce dependence on mechanical energy. A water feature integrated into the landscape reinforces the idea of cyclical resource use while also providing a calming and reflective experience for visitors. The design prioritises passive solutions before introducing active systems, ensuring minimal energy consumption and long-term resilience.

Programmatically, the centre consists of four main components: the kokedama studio, exhibition gallery, retail, cafe, centralised herb and gathering area. Each program is strategically positioned to facilitate a journey of exploration and learning. The Exhibition Gallery provides a platform for environmental displays and community workshops, while the kokedama studio allows visitors to engage in hands-on plant-based crafts that symbolise life and renewal. The retail and cafe areas support local products and artisans, fostering an economy that aligns with sustainability values.

Material selection emphasises locality and tactility. The use of timber, bamboo and natural stone reduces embodied carbon while blending harmoniously with the surrounding landscape. The natural tones and textures create a warm, biophilic atmosphere that encourages users to feel grounded and connected to the environment. Transparency in façade treatment enhances visibility and interaction, reinforcing the idea of openness and coexistence.

From a social and cultural perspective, the ALMA Centre acts as a platform for community engagement and knowledge exchange. Gunung Lambak currently functions primarily as a recreational destination. This project repositions it as an educational landscape that invites students, tourists, and residents to participate in sustainability learning. The inclusion of public spaces and communal programs strengthens local identity while promoting environmental literacy across different age groups.

Addressing the issues of limited tourism utilisation and lack of educational facilities, the project revitalises the site through an architectural intervention that merges environmental, social and economic sustainability. By activating an overlooked site into a vibrant eco-learning hub, ALMA contributes to the broader goal of sustainable urban and rural development in Malaysia.

Ultimately, the ALMA: Eco-Anthropocene Centre represents a vision for architecture that is both reflective and proactive, a built form that teaches, heals and inspires. It demonstrates how design can move beyond aesthetics to become a medium for education, empathy and environmental stewardship. The project aspires to become a model for sustainable tourism architecture where learning and leisure coexist harmoniously within the natural world.

Through its integration of ecological systems, community participation and educational programming, ALMA embodies the essence of the Anthropocene, acknowledging human impact on the planet while striving to restore balance through awareness and action. It is not merely a building, but a living narrative of coexistence, reminding us that sustainability begins with connection and connection begins with design.

Designer: Zulaika Salleh

Supervisor (or Instructor): Dr Ethan Yong

Architecture Project - Multispeciality Hospital

The thesis presents a groundbreaking proposal for a multi-specialty hospital in Gurugram, Haryana, India, integrating the innovative "bio triad" concept. This approach combines biophilic design, biomimicry, and sustainable architecture to create a healthcare facility that promotes both physical and psychological well-being while minimizing environmental impact. The project is driven by the growing need for sustainable and eco-friendly healthcare infrastructure, aiming to set a new standard in the region.

Biophilic Design: Reconnecting with Nature

Biophilic design is central to the thesis, emphasizing the importance of integrating nature into built environments. The concept is rooted in the idea that human beings have an inherent connection to nature, and this connection can significantly influence well-being. Studies have shown that exposure to natural elements within healthcare settings can reduce stress, enhance recovery rates, and improve overall patient satisfaction. For instance, research by Roger S. Ulrich demonstrated that patients with views of nature had shorter post-operative stays, required fewer pain medications, and experienced fewer complications than those without such views.

The proposed hospital in Gurugram incorporates biophilic design elements such as natural light, green spaces, water features, and organic materials. These elements are strategically integrated into the hospital's layout to create a calming and restorative environment. The design also includes therapeutic gardens and rooftop green spaces that offer patients, staff, and visitors a respite from the clinical setting, fostering a connection with nature and enhancing the healing process.

Biomimicry: Learning from Nature

Biomimicry, another key aspect of the bio triad, involves drawing inspiration from natural processes, structures, and systems to solve human design challenges. The thesis explores how biomimicry can be applied to healthcare infrastructure to create more resilient and efficient buildings. By studying how ecosystems function and adapt, the hospital's design seeks to mimic these processes to enhance sustainability and reduce environmental impact.

For example, the hospital's ventilation system may be inspired by termite mounds, which maintain stable internal temperatures despite external fluctuations. By emulating these natural systems, the hospital can optimize energy efficiency, reduce reliance on artificial climate control, and improve indoor air quality. This approach aligns with research by Janine Benyus, a pioneer in biomimicry, who advocates for designs that learn from and emulate nature's time-tested patterns and strategies

Sustainable Architecture: Building for the Future

Sustainable architecture is the third component of the bio triad, focusing on minimizing the environmental footprint of the hospital while maximizing its operational efficiency and resilience. The thesis outlines various sustainable strategies implemented in the design and construction phases, from passive design techniques to the integration of renewable energy systems.

Passive design strategies, such as optimizing building orientation, using thermal mass, and incorporating natural ventilation, are employed to reduce energy consumption. The hospital also integrates renewable energy sources like solar panels and geothermal systems to meet its energy needs, further reducing its carbon footprint. Additionally, the use of sustainable building materials, such as locally sourced and recycled materials, contributes to the overall sustainability of the project.

The thesis also discusses the importance of indoor air quality (IAQ) in healthcare settings. Poor IAQ can exacerbate respiratory conditions and negatively impact patient outcomes. By incorporating advanced filtration systems and ensuring adequate ventilation, the proposed hospital aims to maintain high IAQ, thereby enhancing patient recovery and staff well-being. This approach is supported by research from the World Health Organization (WHO), which emphasizes the critical role of IAQ in healthcare environments.

Conclusion: A New Standard for Healthcare Infrastructure

This thesis presents a comprehensive and forward-thinking approach to healthcare facility design, integrating biophilic design, biomimicry, and sustainable architecture to create a hospital that not only heals but also respects and enhances its natural surroundings. The proposed multi-specialty hospital in Gurugram is designed to promote wellness, resilience, and sustainability, setting a new standard for healthcare infrastructure in the region.

By embracing nature-inspired design principles and sustainable practices, this project aims to prioritize the health of both individuals and the planet. The hospital's design not only addresses the immediate needs of patients but also considers the long-term impact on the environment and the community. As healthcare facilities worldwide face increasing pressure to reduce their environmental impact, this thesis offers a model for future developments that balance human health with ecological stewardship.

Site area - 15.4 acres

Prohect description - 300 bedded multisoeciality hospital

Total area - 62,297 sq m

Coverage - 24

location - Gurugram , Haryana

Heba Rasheed

Guide: Dr.Josna Raphael P.

Biophilic Design: Reconnecting with Nature

Biophilic design is central to the thesis, emphasizing the importance of integrating nature into built environments. The concept is rooted in the idea that human beings have an inherent connection to nature, and this connection can significantly influence well-being. Studies have shown that exposure to natural elements within healthcare settings can reduce stress, enhance recovery rates, and improve overall patient satisfaction. For instance, research by Roger S. Ulrich demonstrated that patients with views of nature had shorter post-operative stays, required fewer pain medications, and experienced fewer complications than those without such views.

The proposed hospital in Gurugram incorporates biophilic design elements such as natural light, green spaces, water features, and organic materials. These elements are strategically integrated into the hospital's layout to create a calming and restorative environment. The design also includes therapeutic gardens and rooftop green spaces that offer patients, staff, and visitors a respite from the clinical setting, fostering a connection with nature and enhancing the healing process.

Biomimicry: Learning from Nature

Biomimicry, another key aspect of the bio triad, involves drawing inspiration from natural processes, structures, and systems to solve human design challenges. The thesis explores how biomimicry can be applied to healthcare infrastructure to create more resilient and efficient buildings. By studying how ecosystems function and adapt, the hospital's design seeks to mimic these processes to enhance sustainability and reduce environmental impact.

For example, the hospital's ventilation system may be inspired by termite mounds, which maintain stable internal temperatures despite external fluctuations. By emulating these natural systems, the hospital can optimize energy efficiency, reduce reliance on artificial climate control, and improve indoor air quality. This approach aligns with research by Janine Benyus, a pioneer in biomimicry, who advocates for designs that learn from and emulate nature's time-tested patterns and strategies

Sustainable Architecture: Building for the Future

Sustainable architecture is the third component of the bio triad, focusing on minimizing the environmental footprint of the hospital while maximizing its operational efficiency and resilience. The thesis outlines various sustainable strategies implemented in the design and construction phases, from passive design techniques to the integration of renewable energy systems.

Passive design strategies, such as optimizing building orientation, using thermal mass, and incorporating natural ventilation, are employed to reduce energy consumption. The hospital also integrates renewable energy sources like solar panels and geothermal systems to meet its energy needs, further reducing its carbon footprint. Additionally, the use of sustainable building materials, such as locally sourced and recycled materials, contributes to the overall sustainability of the project.

The thesis also discusses the importance of indoor air quality (IAQ) in healthcare settings. Poor IAQ can exacerbate respiratory conditions and negatively impact patient outcomes. By incorporating advanced filtration systems and ensuring adequate ventilation, the proposed hospital aims to maintain high IAQ, thereby enhancing patient recovery and staff well-being. This approach is supported by research from the World Health Organization (WHO), which emphasizes the critical role of IAQ in healthcare environments.

Conclusion: A New Standard for Healthcare Infrastructure

This thesis presents a comprehensive and forward-thinking approach to healthcare facility design, integrating biophilic design, biomimicry, and sustainable architecture to create a hospital that not only heals but also respects and enhances its natural surroundings. The proposed multi-specialty hospital in Gurugram is designed to promote wellness, resilience, and sustainability, setting a new standard for healthcare infrastructure in the region.

By embracing nature-inspired design principles and sustainable practices, this project aims to prioritize the health of both individuals and the planet. The hospital's design not only addresses the immediate needs of patients but also considers the long-term impact on the environment and the community. As healthcare facilities worldwide face increasing pressure to reduce their environmental impact, this thesis offers a model for future developments that balance human health with ecological stewardship.

Site area - 15.4 acres

Prohect description - 300 bedded multisoeciality hospital

Total area - 62,297 sq m

Coverage - 24

location - Gurugram , Haryana

Heba Rasheed

Guide: Dr.Josna Raphael P.