The label ‘refugee’ invokes a patchwork of hopeless and sombre images: the washed ashore body of a 2-year old Syrian boy, a packed boat drifting in the Mediterranean Sea, cities reduced to ruins in Yemen, and run-down camps in the Horn of Africa.

The objective of this project is to create shelters at the 24 South Pargana district, West Bengal for one such refugee community— the Rohingya— dispersed within India. The Rohingya population is a predominantly Muslim ethnic minority from the North-Western Rakhine state of Myanmar. Consistently attacked and systematically discriminated, they are often referred to as ‘one of the most persecuted minorities in the world.’

When refugees become homeless, they are also deprived of a sense of belonging and detached from their familiar culture and ways of living. Therefore, when this project encounters the mission of making shelters, it also meets the challenges of recreating intricate imageries of identity and memory encapsulated within ‘home.’ Therefore, this project proposes shared institutions, accessible to both the Rohingya settlers and the members of the receiving community, alongside which resilient houses will grow incrementally. With the assistance of such spaces, including a community centre, refugees are accommodated into the local people’s everyday through visibility and interaction, which in turn promotes their sense of legitimacy and informal inclusion.

Today, most countries turn away refugees fearing that they will be a burden to the welfare and resources of the nation. However, recent studies have established that, on the contrary, refugees, when given the right circumstances to integrate with the host community and into the labour market, can become welfare-enhancing assets to the domestic economy. Therefore, this project also includes a vocational centre to enable the Rohingya to make positive contributions to the economy. School and health care facilities are introduced to sustain the host village and improve its human development indicators.

It is important to note that this project is not an argument for unlimited and uncontrolled immigration. Every country will have an incentive to limit accommodating non-natives to keep the population growth in check and to avoid undue strain when it comes to sharing limited resources. However, this should not come at the cost of negatively impacting the human rights of anyone. Sending back those Rohingya refugees who have already made it to India would mean they will meet the certain fate of persecution in Myanmar. Therefore, there should be some consideration to international sharing of responsibilities, and by extension, distributive equality when it comes to hosting refugees.

Despite common assumptions about the temporariness of refugee settlements, in recent times a refugee stays in such a settlement on average for 17 years. I have acknowledged the protractedness of such camps with a flexible layout and morphable typology, and have attempted to design a settlement that is organically and perpetually transforming to adapt to the needs of the inhabitants. Moving away from the restricted definition of sustainability that favours material permanence, I adopt a transient take on sustainability that values resilience and nurtures a sense of place.

Bamboo is used primarily for the construction of refugee houses within this project owing to the availability of bamboo within Hardaha, moreover Rohingya communities themselves have used bamboo extensively for their houses back in Rakhine. It is sustainable in nature and also can last close to 200 years, if preserved well. They are easy to build with and takes less time to build, It can quickly be assembled and dismantled, leading to more flexibility in its usage as a building material.

Utmost importance is given to services within the site - Waste accumulated will be categorized and organic wastes will move onto compost pits while rest would end up in landfill or be recycled. Ground water is tapped and pumped onto overhead distribution tanks. Tanks will be spread within the site, making it easy for refugees to collect water and store in troughs. Rainwater is collected and filtered through the process of sedimentation. Solar power is majorly used as a power source. All buildings will have solar panels installed in them to make it energy efficient.

Ultimately, renouncing both makeshift shelters and pre-fabricated structures, the design process for the Rohingya community attempts to capture flexibility and endurance that will be resilient to disruptions and responsive to a civilisation in flux.

This project observes how materiality, space and permanence evolve over time. The dominant focus here is to see how we can better integrate refugees and build their capacities so that they can become useful to our society instead of merely remaining as a marginalized group used as a tool for xenophobic rhetoric.

This work is dedicated to refugees everywhere, fiercely battling war, hunger and the sea, for the sake of a normalized everyday, with the urge to make true again a distant memory of a familiar ‘home’.

2020

0000

Location: Hardaha, West Bengal

Typology: Humanitarian architecture (Rohingya Refugee crisis)

Site Area: 16 Acres

Total Built-up: 16178 Sqm

Malavika Madhuraj

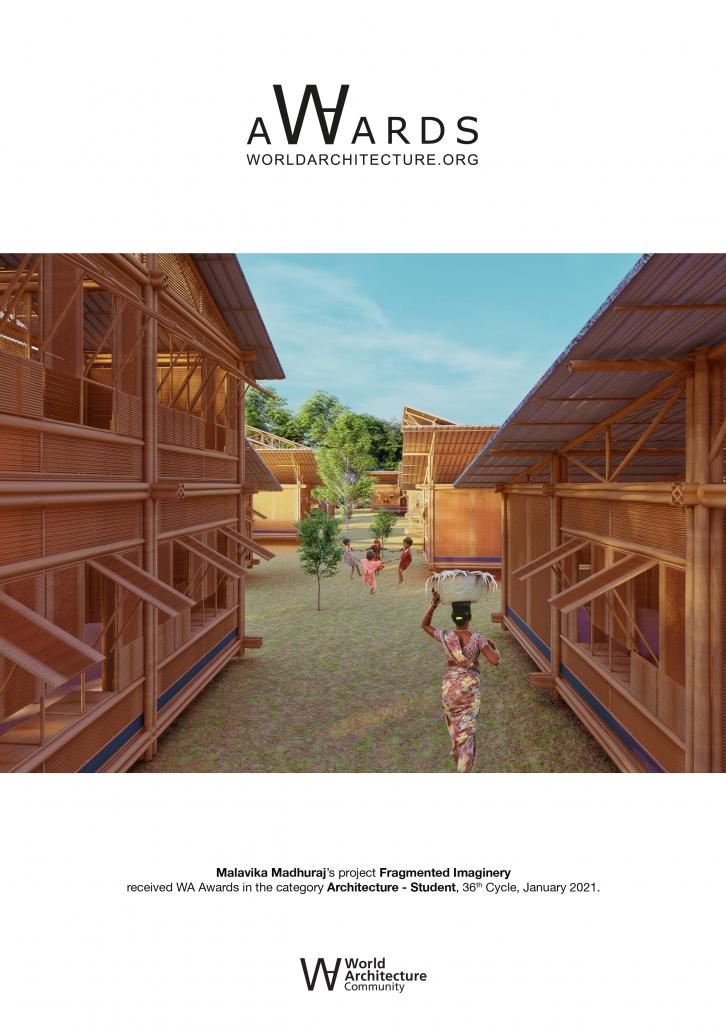

FRAGMENTED IMAGINERY by Malavika Madhuraj in India won the WA Award Cycle 36. Please find below the WA Award poster for this project.

Downloaded 37 times.

Favorited 6 times