Submitted by Tarun Bhasin

Day 2 Summary on Z-Axis 2018 Conference in India

India Architecture News - Sep 07, 2018 - 21:40 15527 views

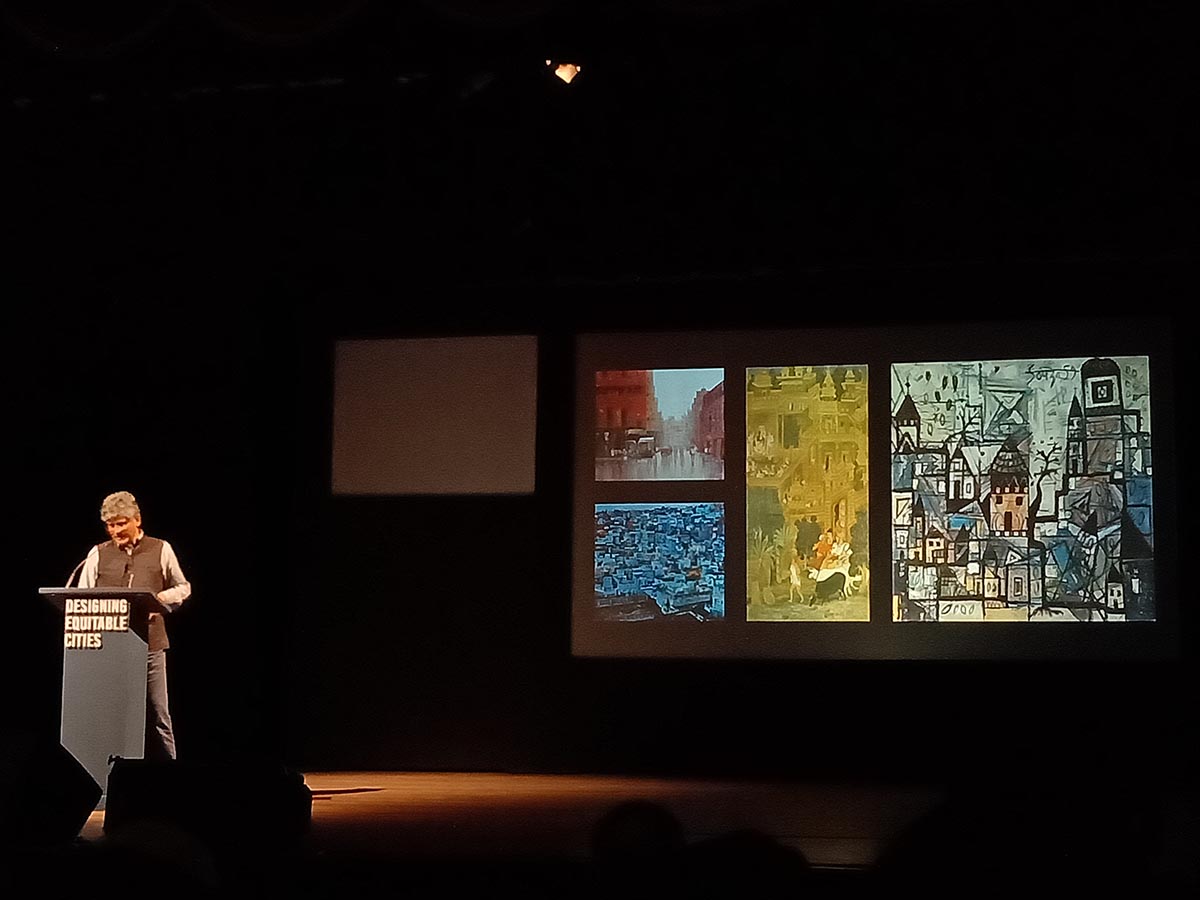

"The elite population today is involved only in the creation of a quality life and are no longer involved in the creation of quality society," remarked Rahul Mehrotra sharply. He began the deliberations on Day 2 of Z-Axis Conference titled "Designing Equitable Cities", organized by Charles Correa Foundation at Kala Academy, Panaji from 6-8 September.

Rahul Mehrotra's comments were supported by visualized data on migration, on looking at different forms of poverty and inequity at a national scale to give the audience an idea that the entire country is in a state of 'Flux', a sort of a transition state that has never been thought of and designed for. The presentation was layered, beginning with the definition of spatial equity, that lay emphasis on interrogating crossovers between social sciences and design because while one deals with critical thinking, the latter deals with a speculative form of thinking.

His proposition was that equity must be looked at diverse scales - at the planetary scale, the metropolitan scale and at the scale of a building - to provide a holistic analysis of the situation and only then could design become instrumental towards addressing the issue. And the precise data on migration or inequity of water visualized across the scale of India provided insight into a new kind of population that is entering Indian cities and gave a hint to what their aspirations might be. He called these newer populations the 'agrarian non-agrarian' - people no longer reliant on land, but socio-economic mobility - who are the new urban-rural and will come to define the future of informal settlements in Indian cities, since, they have been marginalized and overlooked due to the gaps in planning. "Indifferent forms of inequity are perpetuated by indifferent forms of poverty and policy" he exclaimed. From the scale of the material poverty and lack of amenities to the scale of cultural poverty or indignity, he addressed the audience on the issues these newer populations lacked, stating how distressful it is to realize that the urban household is no longer determined according to their family structure or needs but on their income.

To give insight into how this could be corrected, he gave examples of two of his works - Hathigaon and KMC Corporate Office. In the former, a marginalized community with a predominantly Muslim population within a predominantly Hindu state was given a landscape with a freshwater source within a geology that faces scarcity of water, thus reversing the inequity. Considering that the elephants of the Mahout community in Hathigaon have to face harsh conditions since they are not residing in their natural habitat, the focus on the generation of a landscape based around a water source creates an amicable atmosphere for the species, providing equity within the community whose social structure is dependent on the elephants itself, thereby, propagating interspecies empathy.

While the former example showed interventions at a community level, the latter showed empathy through design through the scale of a building. The KMC Corporate Office has a double skin that acts as a visually dynamic facade and a humidifier to the air entering the building. The skin is wrapped with hydroponic trays and drip irrigation systems, allowing for growth of a variety of plant species that need care and maintenance. While in a normal corporate office the landscape stays outside, and the gardeners who tend them are never treated as a part of the office culture, the need of the skin in KMC allowed the gardeners to perform within the office domain, thereby, putting them in direct contact with every other person in the office.

This transgression of the soft threshold is what bridges the cultural gap between the different income groups and creates empathy through just 'eye-contact', said Mehrotra. These interventions were, of course, realized after being sensitized from the observations of patterns of 'Flux' at a planetary scale, and he ended the presentation on the same not, urging the audience to pay attention to creating 'transitions' at every scale possible, since at present, they lie completely outside the imagination of designers. This gave a closure to his talk and in a way provided a link to the topics chosen by other panelists who presented after him.

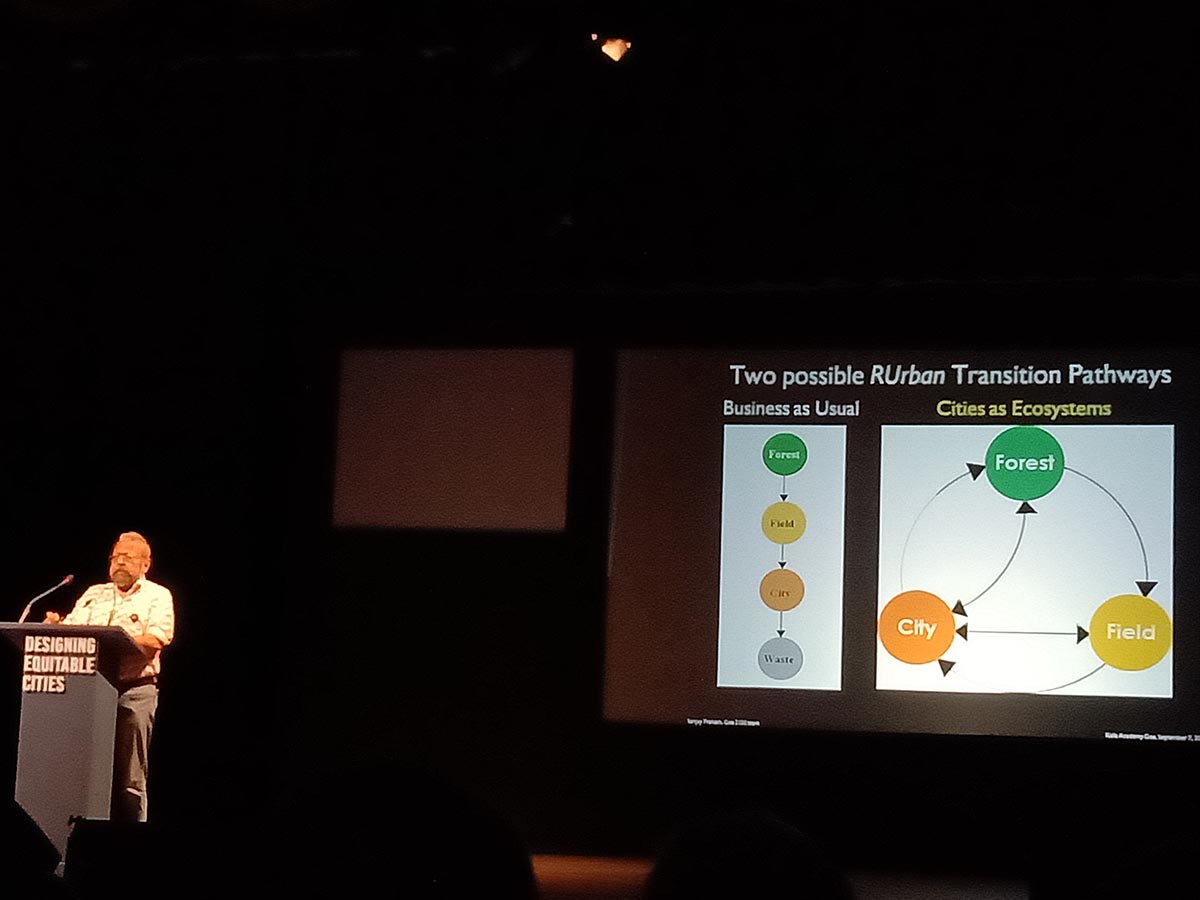

The next presenter on the panel, Sanjay Prakash, discussed his competition entry 'Goa 2100' for Sustainable Urban Systems Design competition, World Gas Conference, in Tokyo in 2003, made in collaboration with Rahul Mehrotra and Aromar Revi. By explaining the design for the competition, he provided a logic analysis on a number of issues encompassing present situation from climate change to resource scarcity, to present systems through which we monitor and analyze our performance on the sustainability index. "Although you can achieve sustainability without equity, as the rating systems do, it is a false notion" with this statement, he revealed how businesses feel guilty for reducing planetary resilience, and in the absence of notions of sufficiency they co-opt for using just building efficiency as a tool for monitoring sustainable growth, which inequity in the long run.

He explained two concepts of 'Death by Urban Sprawl' where he talked about how American city sprawl was supported by cheap oil prices, a resource not available to Indian cities, and thus replacing the aforementioned form of growth with 'Urban Consolidation' - breaking the urban sprawl into innumerous loci, so that stresses on interdistrict mobility could be reduced by creating sufficiency at the level of neighborhoods and districts. He further explained how limits to urban sprawl and consolidation could be predicted and met by conditions of distress that would be delineated by the parameters set by indicators of equity. He further delved into ecosystem designs, managing health of urban nuclei, and simple knockdown processes that could allow settlements to move efficiently, and transform without a negative footprint. He ended his presentation by forwarding tactics that, if followed, would help societies manage physical stocks and flow to maintain equity at both, personal and public level.

When talking about equity and ecosystem design, we almost always overlook equity in terms of nature or the 'natural'. Since, human understanding of history provides credibility to only the built components, rather only the static components, anything that is not visually comprehensible or not physical/tangible is not valued. On this note, Mohan Rao started his arguments on equity in the context of nature. He talked about nature as a determinant and equalizer of urban inclusion that creates balance on the basis of access to resources, purpose towards morals and ideals, cultural growth and upliftment of livelihood. "But, how does one start including nature as part of urban equity if entire landscapes have been ignored from urban history?" he questioned.

Through his own works like the restoration of temples of Hampi, he informed the audience how since the beginning something, as defined as temple architecture, did not follow a tabula rasa, but carefully understood the geological context and understood the nature of the land. He showed how the placement of temples of Hampi was done on the least valuable portions of the site, and the fundamental reasoning behind this approach was simple - respect things for their age and time - putting geology first, then hydrology of the area, then the cultivable soil, then the flora and fauna, and lastly heritage structures relevant to human memory. According to him, what is natural and what is not, is defined by the level of penetration humans are allowed in nature in a strictly non-hierarchical manner.

"Are we benevolent enough to allow nature to exist in the city?" the sharp question provided a sudden turn to his presentation and began a comparative analysis between traditional interpretations of nature within architecture and modern interpretations. He began by stating examples in ancient scriptures, scientific edicts and cultural forms in architecture that exemplify flora and fauna as a part of human society by careful placement within the language of built forms. By making them a part of the human spatial syntax, religion and culture takes a backseat and allows nature to attain autonomy and interpersonal identity in human society. This, Mohan Roa, explained was fundamental towards creating a sense of belonging and towards maintaining notions of equity in the society.

He continued to explain how modern architecture and urban design has been created a natural exclusion either through design that uses control over activity or manufactured inhospitable conditions or by the total apathy that involves the complete destruction of common goods. With the comparison, he pointed out how we, as a discourse, are missing to take notice of the fragmentation of livelihood, knowledge, and community values by obliterating patterns of nature that are relevant not just for the poor but to all segments of the society. His presentation encompassed three possible outcomes to our approach - nature in the city, city in nature, or city versus nature.

While the first three presentations helped in creating a degree of complexity about the ideology of approach, Alejandro Echeverri's presentation sought to direct the audience to find their own role within the larger gamut of world scenarios, market forces, nature, and empathy. According to him, as architects, we cannot do all the work but we can provide solutions for the physical and the natural, however small and not always built. He talked about his city of intervention, Medellin, where he performed as the city architect for over a decade. He elaborated on his partnership with the mayor and how informed political forces helped him achieve his goals. His presentation focus on explaining the demographic scenario of the city where almost 70% of the population was facing poverty at some level and inequity in many forms. The scenario was not about bridging a gap since most of the population was on the same side of the spectrum. This meant that people of the city were equal but that equality wasn't enough.

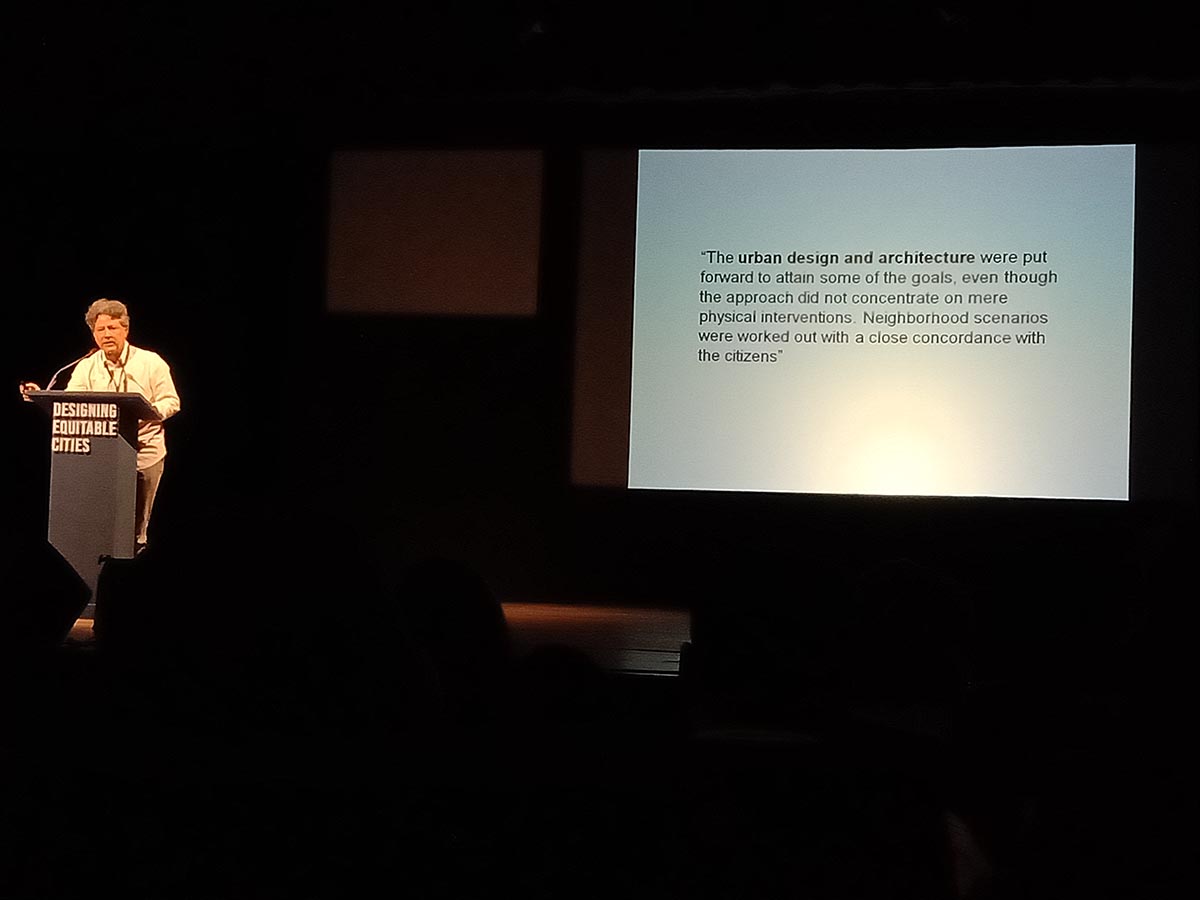

"When a city is completely equal, it is not about reducing the gap but increasing opportunity" With this statement he opened up about 'Social Urbanism' in which architecture and urban design are created in relation to larger social programmes to develop a physical presence for social values within said territories. Echeverri then went on to explain his 'Urban Integral Projects' that sought to create a network of such small interventions at the scale of the city for continuity of social innovation, not by urban development but urban acupuncture.

Medellin was once plagued by drug cartels and small mafias that had taken over barrios and demarcated territories. This hampered the communication and interaction between barrios which was proving detrimental to the entire city. After providing the political context, he showcased an example where two barrios on either side of a valley were controlled by two different cartels.

The site became a notable example of Social Urbanism, by drawing a bridge that ended up connecting both the barrios physically thereby destroying the autonomy that both cartels enjoyed before. "Where militias were dividing one barrio from another the bridge became a powerful tool to change the condition" exclaimed Alejandro Echeverri, as he then went on to explain nuances of the programme that involved articulating infrastructure budget with the cultural budget; and understanding the relation of public space with interior political conditions of individual houses. Through his own works, he was able to craft in the eyes of the audience, a defined position, and scope of the work of an architect within a city witnessing transitions.

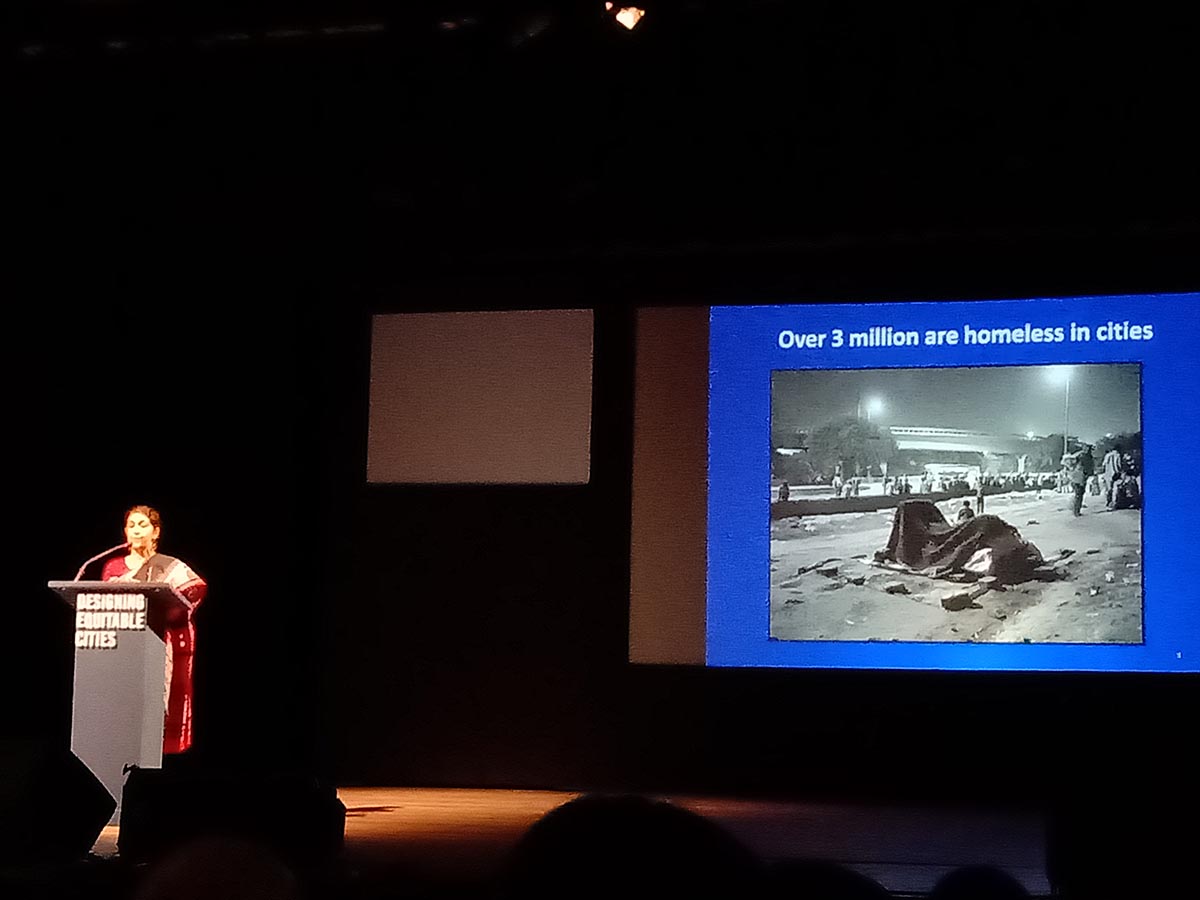

The presentation on stated-equality was followed by Shivani Chaudhary who opened note on the need for an equitable and human rights centered approach towards the development of the city. While the previous presentation drew focus on the role of the architect, this particular lecture drew importance on the mind of the architect and the level of sensitivity required in city-wide operations. Starting with data on migration, homelessness, she explained how there is a housing deficit of over 19 million in the country with 11million dwellings lying vacant due to market speculations in hopes of generating profit. Her presentation was filled with an angst towards witnessing housing shortage and vacant urban spaces, in light of homelessness and forced eviction on the pretext of city beautification, infrastructural projects, wildlife protection and conservation, and disaster management. "We are seeing a shift from welfare based to market-based governance, policies that create prejudice against poor, increase segregation, gentrification and gender-based violence" Shivani Chaudhary explained 'Apartheid Cities' from her own observations of notions and elements of design, neighborhood planning, and safety versus security.

With many examples, Shivani Chaudhary listed the lopsided management done by the government and supported her arguments with data procured from her own organization, the National Eviction and Relocation Observatory. She pointed out, that people who were indispensable to the functioning of the city were being labeled as ugly, unwanted and dispensible. She drew the relation between eviction and crime against women and children stating, "The simple act of human eviction leads to a series of human rights violation detrimental to the social fabric of the country." She left the audience with elements and recommendations to enhance dignity and equality as part of urban design and planning discourses.

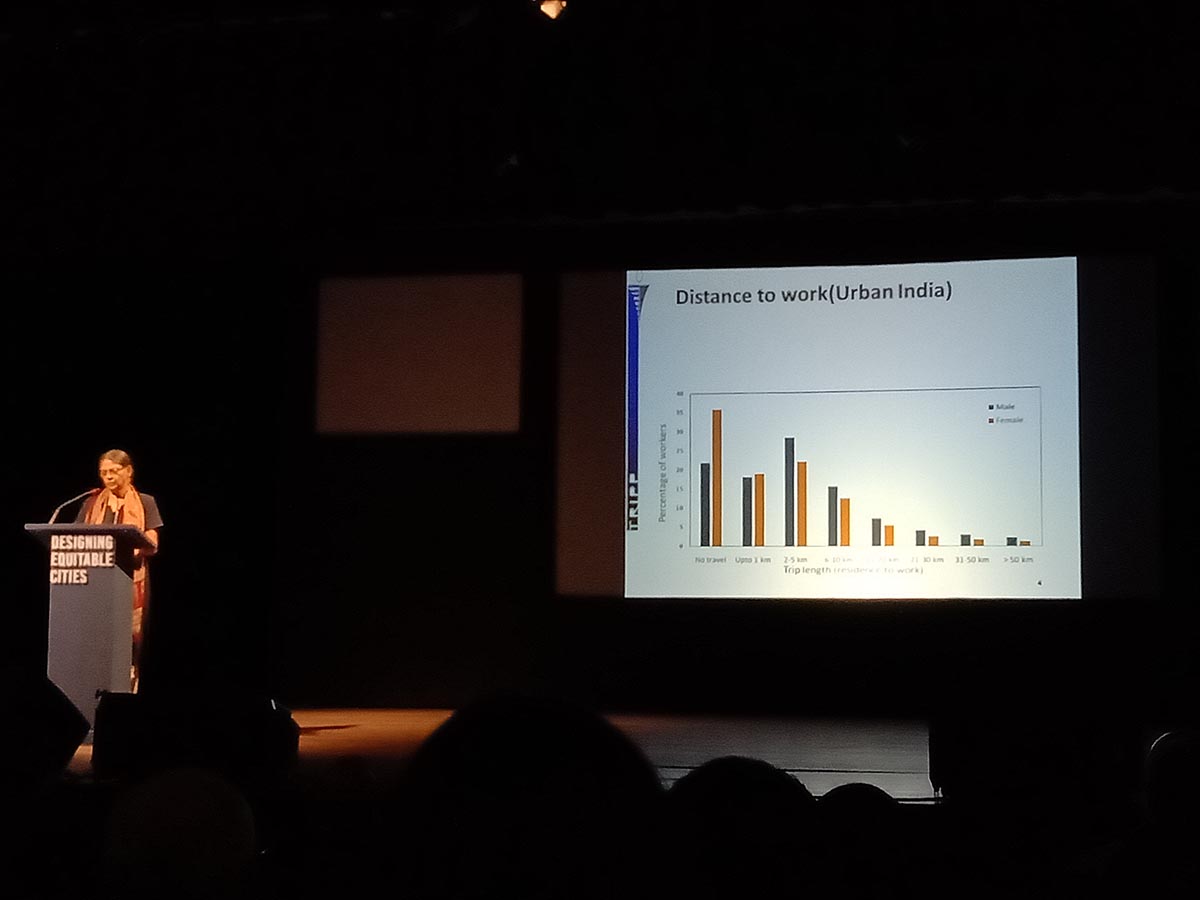

From reducing of cultural poverty by the provision of dignity, equality, and human rights in operational methodology revealed by Shivani Chaudhary, the audience was exposed to arguments of material or rather infrastructural poverty, delving deeper into the lives of 'subjects' the audience is meant to serve - the agrarian non-agrarian. "What is the geographical space I consume every day and how do I consume it?" with this question Geetam Tiwari opened her arguments on equity in a city, by talking about the importance of mobility and transportation planning. Her presentation was filled with graphs and census reports and statistics to demystify the fad that we need wider roads, or flyovers or city metro (for smaller cities). She pointed out the fact that a majority of the population was within walking distance from their place of work, yet there has not been any consideration given to pedestrians and cyclists in planning systems.

She revealed furthermore the administrative concerns that termed Indian roads as chaotic and pedestrians as lawless. Stating examples from historic decisions of city planning departments and even courts, she revealed the gaps in public transport and road planning in India. She pointed our through examples how certain decisions were counterintuitive and turned the roads into a perpetual chaos. Drawing from Charles Correa's observations that informal settlements come to place in proximity to the place of economy/work, Geetam Tiwari explained how Indian cities needed to consider local movement in order to build more resilient neighborhoods and equitable infrastructure. Urban improvement, informal settlements & access to employment come together as she left the audience to reflect on the history of mobility in India and it's long-term effects.

Having stated 'ideologies' of different 'scales', 'methodologies' of 'actants', and 'nature of lives' of the ones 'acted upon', Jagan Shah with his presentation moved the deliberations towards a drive for the 'action' itself. His talk was a skeptical thought experiment on the notion and present situation of equity in the country, bringing contrasting and provocative views from both binaries, and reminding the practitioners of past failures that could not be corrected and consequent societal anomalies that design could not treat anymore. "Poverty is an overwhelming reality? What chances do we have of removing inequity?," he noted.

His talk revealed the prejudice and bias in ways cities spend on transport needs and the ways in which their fundamental operations are constructed - that overwhelm both the elected representatives and the population of the city. Labeling building of capital assets as extra-municipal operations and processes of undemocratic needs and means, he drew attention to figures and maps of recent informal settlements that were a result of inward urban migration into smaller towns and cities. "These blobs where planning doesn't exist are the places where we need to focus on, for this is where inequity is born".

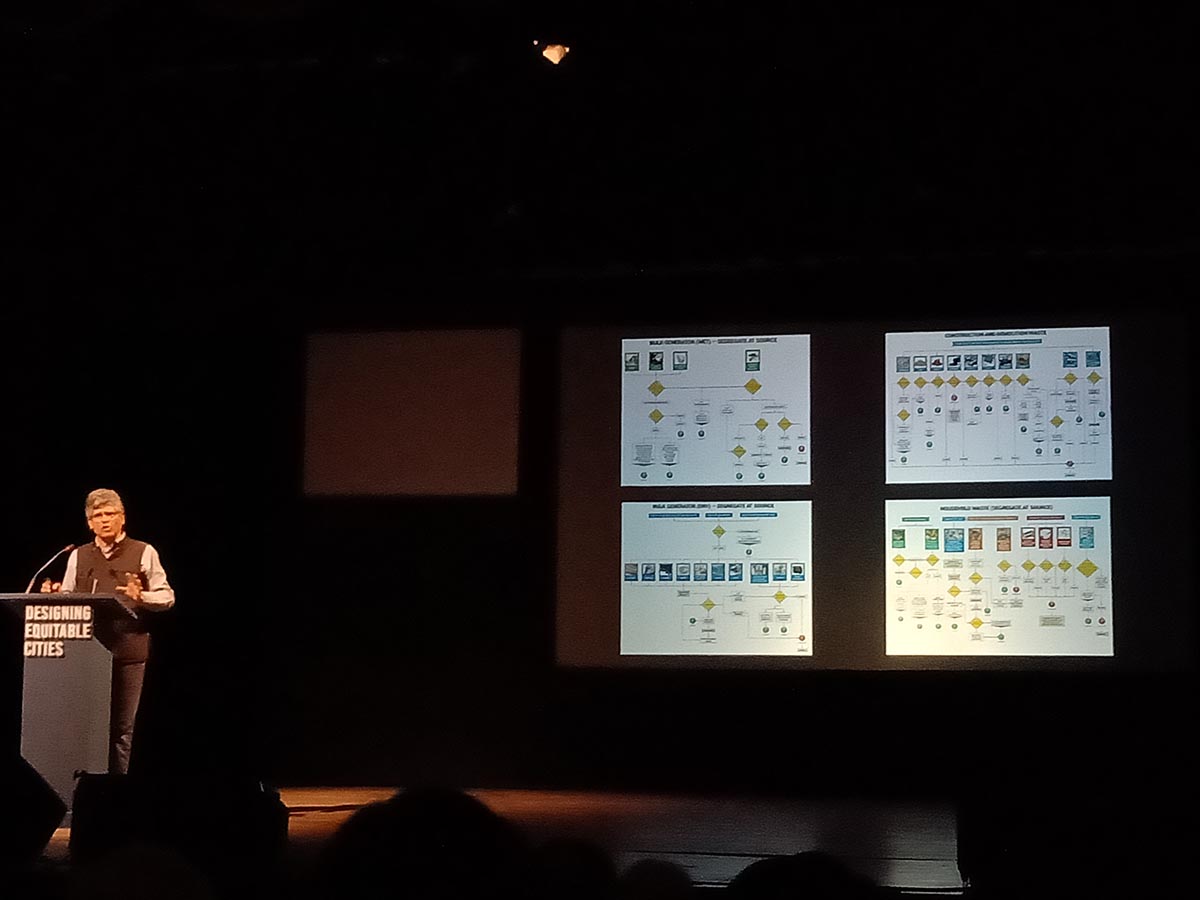

"The gap between information and visualization of data is what is plaguing the decision-making processes today and driving ideology to the corner." His statements revealed more on the general lack of confidence and trust of society in the decision-makers today. According to him, it was not unfounded as he saw the municipal departments as inadept and ill-informed; and this is where his actions found ground for existence.

He talked about the need to shed utopian presumptions and speculative ideologies to embrace a more informed analytical approach fuelled by data and technology, and ended his presentation with an imagination of data systems to bridge the gap between information and civic discourse for better accountability - so we are no longer just debating on ideology!

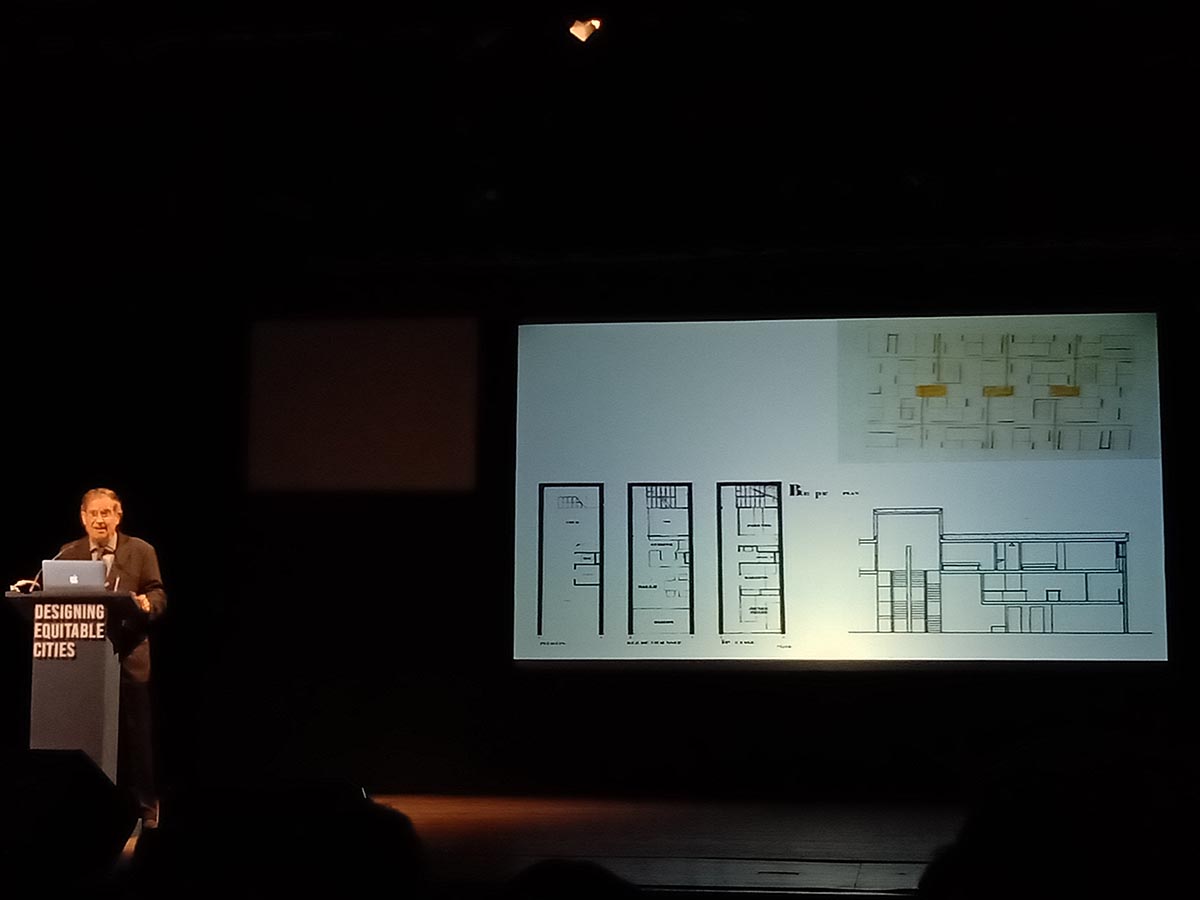

Jagan Shah's lecture in a manner provided a certain all-roundedness to the day, and a degree of closure; so what was left of the key-note lecture was to provide a summation to all the previous lectures of the day, and to bring all arguments in place with a single narrative. With this Joan Busquets began explaining through the history of the urban development of Barcelona, the various images and transitions that any city would have to go through to achieve a level of equilibrium. He looked beyond the beautiful identity of the city's buildings and plazas, and Gaudi, to reveal how difficult situations were created when the city underwent transitions. He stated that capitalist cities' growth equals imbalance, and then revealed the periods/steps of infrastructure development through which a city enhances its urban threshold.

By stating transitions of Barcelona, his focus came on the informal settlements that grey on its periphery during the 19th century despite massive planned efforts. "Once you look informal settlements you realize that the working class population is building with logic and have similar elements of design within a neighborhood" By legitimizing the process of creation of informal settlements, he called for a requalification of the city in terms of providing facilities and amenities to civic spaces of this gigantic urban periphery that have been deprived of such benefits. This rationalism, he proposed, allowed for the expansion of capitalism as well, but accomodated the need for change.

Having explained Barcelona at its stages, Joan Busquets shifted the focus to look at the planning during the Barcelona Olympics that inspired the London Olympics model. The requalification of the city on the basis of its informal settlements and urban peripheries was supported by detaching different forms of urban traffic and creating continuous green patches that spanned neighborhoods and districts. Identification of vacant plots, name-giving, and regulation into a mix of public space, affordable housing, private development and infrastructure, a gamble at the time, was the only rationale that could provide direction to the irrational metabolism of the city.

With this he opened his thoughts on numerous cities, some rational, some ideal, capital cities, walled cities etc. to explain the individual logic behind the design of those cities that led the audience to question the notions on the spirit of growth, regularity, density, metabolism, mobility, overlapping of time and memory, and irrational principles of neighbourhood planning and the idea of the scale of neighbourhood within the city. This provided for a way to debunk the ideology of conformed planning practices or 'the masterplan' to shed light on the more entrepreneurial values and methodologies that are demanded due to the diverse morphological behavior of cities today. "We have to understand the city as a place where we get something that we cannot get in the countryside," he explained and ended the lecture by drawing references from Charles Correa's 'A Place in the Shade' to explain the more emotional needs of cities that the current planning systems did not account for - such as the mystic spaces as opposed to mere open spaces, and celebratory spaces as opposed to mere public spaces.

Day 2 of Z-Axis 2018 at Kala Academy, Panaji on 7th September, ended with a Q&A session with the audience, and with Kaiwan Mehta and Joan Busquets discussing with the audience, the need to shun the top-down approach and putting the notion of improving urban condition above the idea of a masterplan, providing a closure to all previous presentations of the day and the event so far.

All images © Tarun Bhasin