Submitted by Antonello Magliozzi

Giordana Ferri on “the architectural design behind the social project”

Italy Architecture News - Nov 05, 2022 - 14:47 2656 views

“Today, social housing is based on a collaborative model that affects the neighborhood level”. This is how Giordana Ferri summarizes the current evolution of social housing in an exclusive World Architecture Community interview. An interesting conversation where she speaks passionately about a concept that has developed slowly over time to link two types of projects: an architectural-functional project, which includes different types of housing and services, and a collaborative project that can be likened to voluntary forms of association at the neighborhood level, such as the social street. “There are many connections between these two types of projects”, and this is why, according to Giordana Ferri, social housing needs an osmosis between the targets of form, function, as well as the social ones, in an iterative way. A view according to which social housing becomes an urban paradigm of ESG policies that combine public and private interests for the social and environmental regeneration of the city.

Giordana Ferri. Image © Giordana Ferri

How did Giordana Ferri come to such statements? In order to answer this question, it is important to first say that Giordana is an architect who has always been involved in the study of housing forms other than traditional ones. She has indeed mainly dealt with residential design in urban regeneration projects, with particular attention to the concept of services and common spaces, cohousing buildings and experimental programs of social housing. During her professional life, she first worked as a freelancer and collaborated extensively with the University of Milan, and then, from the early 2000s, began working with Fondazione Housing Sociale (FHS). Today she holds the position of executive director of FHS and is responsible for the concept design of new residential interventions, as well as the development of tools for the social housing management. In that role, she contributed to the publication of two books that summarize her efforts, Social Housing, handbook for designers1, and Starting up communities, a design kit for collaborative living2.

Social Housing, a handbook for designers. Image © Fondazione Housing Sociale

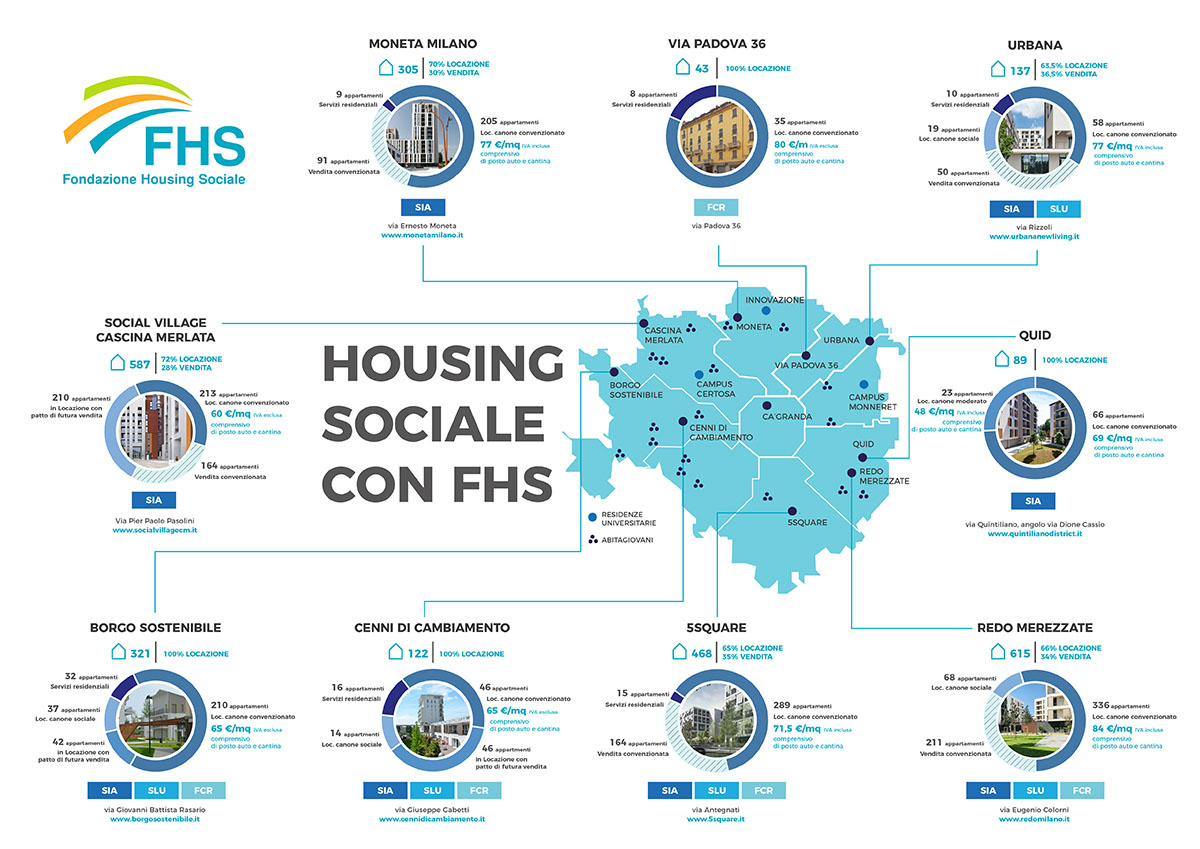

These publications were conceived as a means to open dialogue and disseminate the views of some of the more advanced forms of housing policy. They constituted, in effect, organs of dissemination of achievements in this field in Italy on a national and international scale; to expand the knowledge of social housing, best practices and knowledge acquired by the authors. In this sense, they represent Fondazione Cariplo | FHS's 20-year commitment to the issue of emergency housing in the Private Social Housing sector through the grant-making approach. In fact, today the Foundation is mainly active as a promoter of the social housing sector as a social-technical advisor to funds investing in Italy, through assistance on both urban planning, architectural and social aspects, and on the social development processes of resident communities. All its interventions are invested by Fondo Investimenti per l’Abitare di CDP immobiliare sgr, and many by Fondo Immobiliare di Lombardia | Redo, which actively contribute to the provision of social housing.

FHS Milan map. Image © Fondazione Housing Sociale

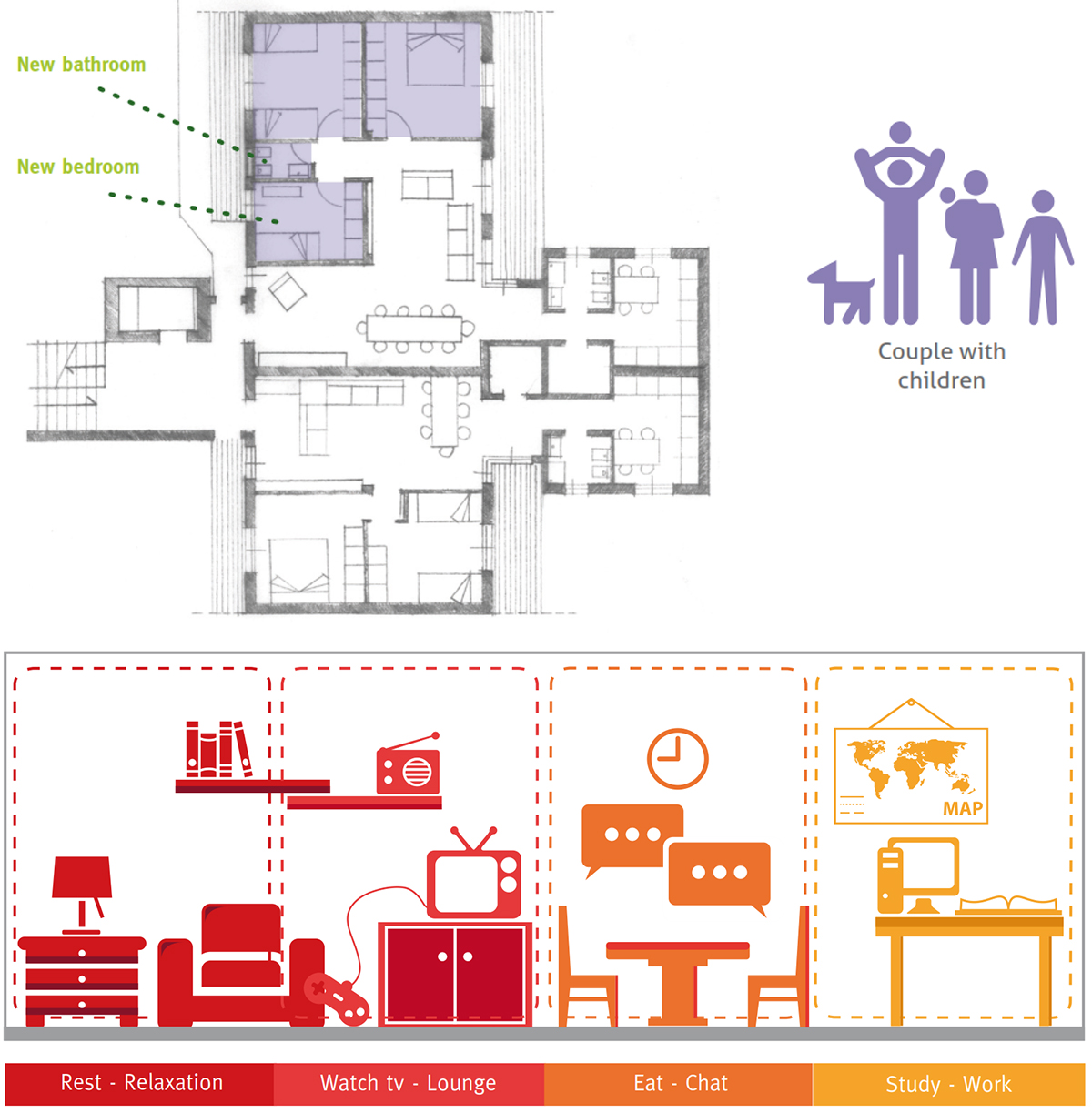

Giordana tells us that the project definition process requires an overall balance in "functional mixity" and a focus on meeting specific rules related to indoor and outdoor spaces. In fact, speaking about her experience, she says, "in our social housing projects, traditional housing types make up 70 percent of the total, while the remaining space is allocated to other special types.” These are, for example, foyers: apartments for temporary sharing among families, co-housing residences for the elderly, co-living units for young people, and studio housing for professionals. Special types can also be residential services for the third sector. These are rented out to organizations that use them for specific social projects to benefit people with disabilities who decide to live on their own, or to benefit new adults, mothers with children removed from the family, relatives of sick children, children's communities, etc.

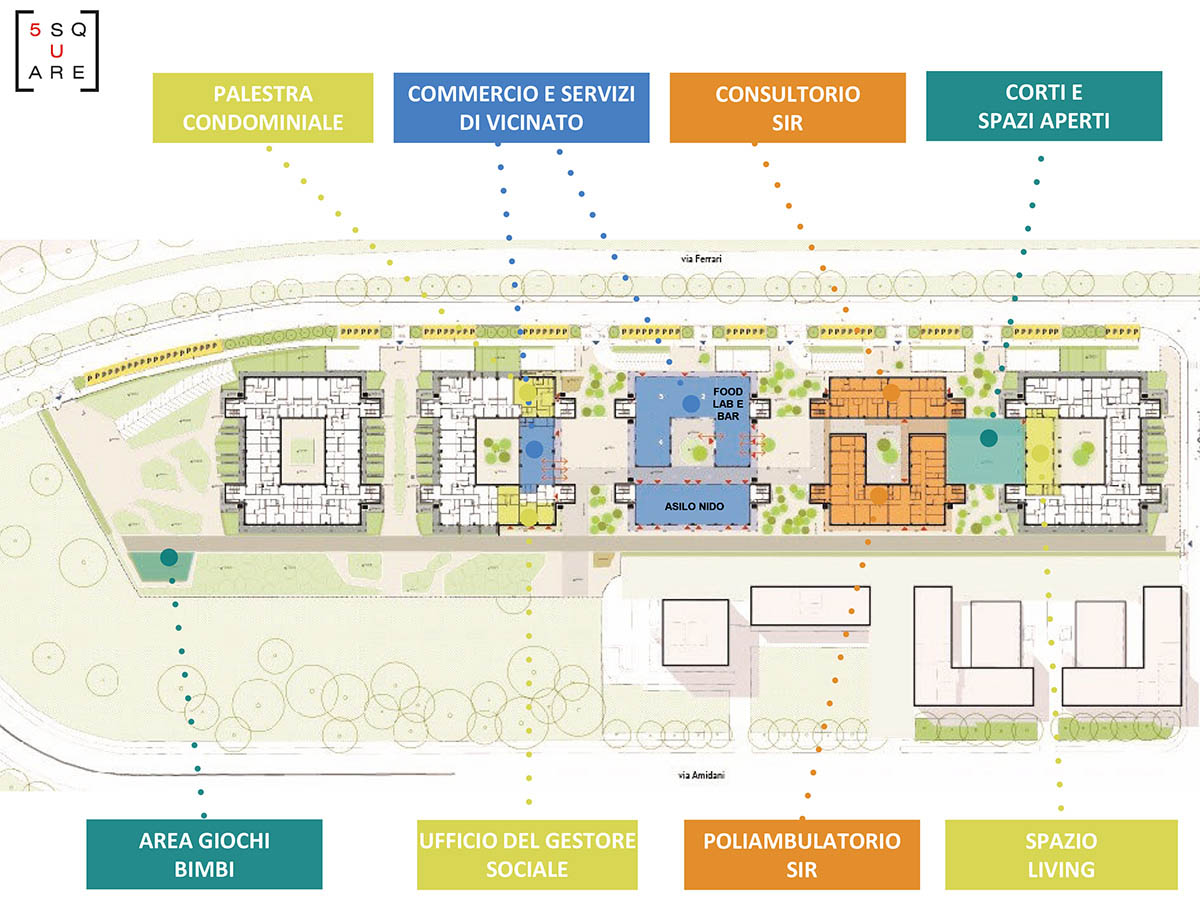

5Square Project. Image © Fondazione Housing Sociale

In the architectural design of the social project, "the hierarchy of spaces beyond living space" also becomes important. It is necessary for common spaces to be traversable and open. "Entrances to buildings should," for example, " be able to overlook a common open space." "Semi-public spaces generated within buildings are in fact widely used even unintentionally, and in these: 'people stay' and chat safely, children play independently. This depends a lot on the architecture, the form of the master plan, which should create protected but open spaces." According to Giordana, such spaces should then be enriched by non-residential hybrid amenities containing commercial functions or cafeterias, so as to generate job opportunities for the residents themselves, as well as cultural centers and landmark elements at the urban level, not only for the neighborhood they belong to.

5Square Project. Image © 5Square

Today, doing social architecture does not mean doing cheap or low-quality construction. In this regard, Giordana points out that: "our interventions are usually designed by recognized architects, in some cases even famous ones such as Snohetta Studio, Barreca La Varra, MAB, Botticini". For example, 5Square, an extraordinarily innovative project recently completed in Via Ripamonti in Milan, provides sustainable and quality architectural solutions for the renovation of five buildings that were never completed and abandoned for decades. This is a project by Studio Barreca-La Varra, which placed the circular economy at the center of its choices in both the architecture of the buildings and the outdoor common spaces. Another example of design quality cited by Giordana is the residential complex in Via Cenni in Milan, by architect Fabrizio Rossi Prodi. In this case, the new social housing complex is home to a variety of uses and generous green spaces. Moreover, the nine story tower buildings boasts an architectural choice worthy of the primacy of the first nine-story wood-frame building.

Cenni di Cambiamento. FHS. Image © via Vimeo

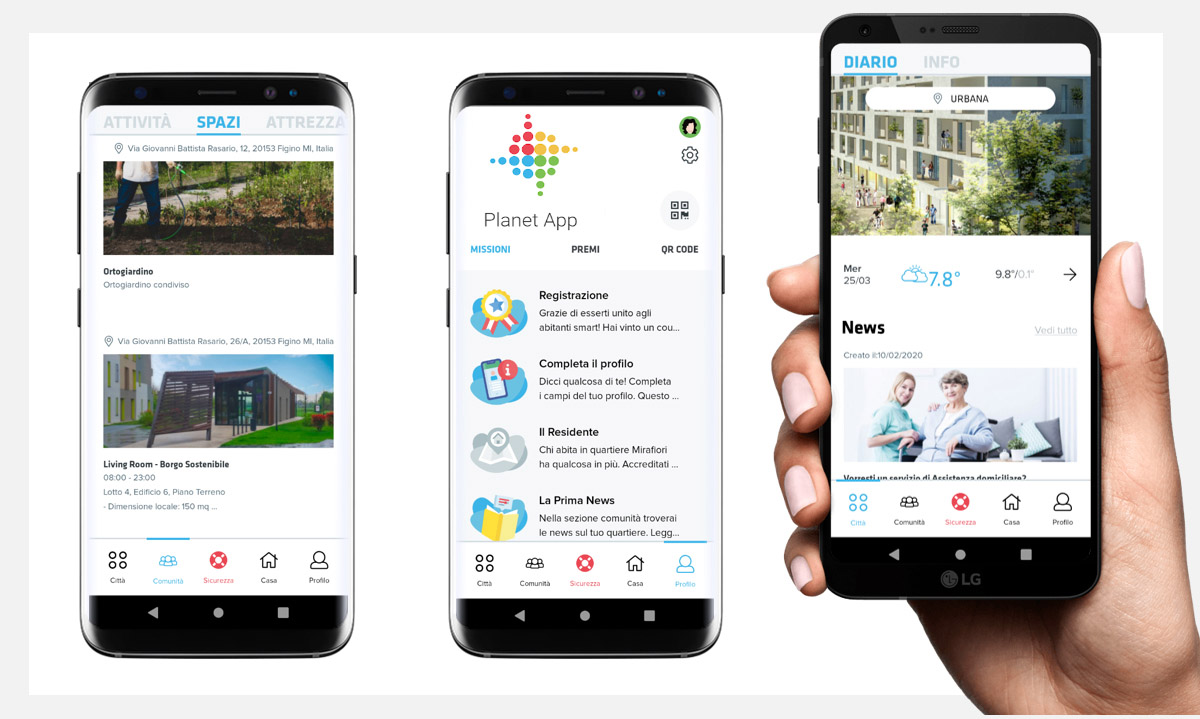

Such design choices highlight how social housing cannot disregard the sustainability of interventions, and indeed that environmental compatibility is precisely a fundamental cornerstone of any project. Actually, Giordana tells us that: energy saving "is one of the main goals we set ourselves". Investments related to such interventions are often reported with a GRESB scoring, or with LEED certifications. In addition, "in many cases the buildings feature IOT sensors and have an app that tenants can use to check what their consumption is, while participating in other shared activities". In fact, the app has "a dashboard with two functions: one for the community, for managing the agenda of the shared spaces, and then another for monitoring consumption that sometimes ties in with playful-competitive activities for consumption reduction."

FHS app. Image © Fondazione Housing Sociale

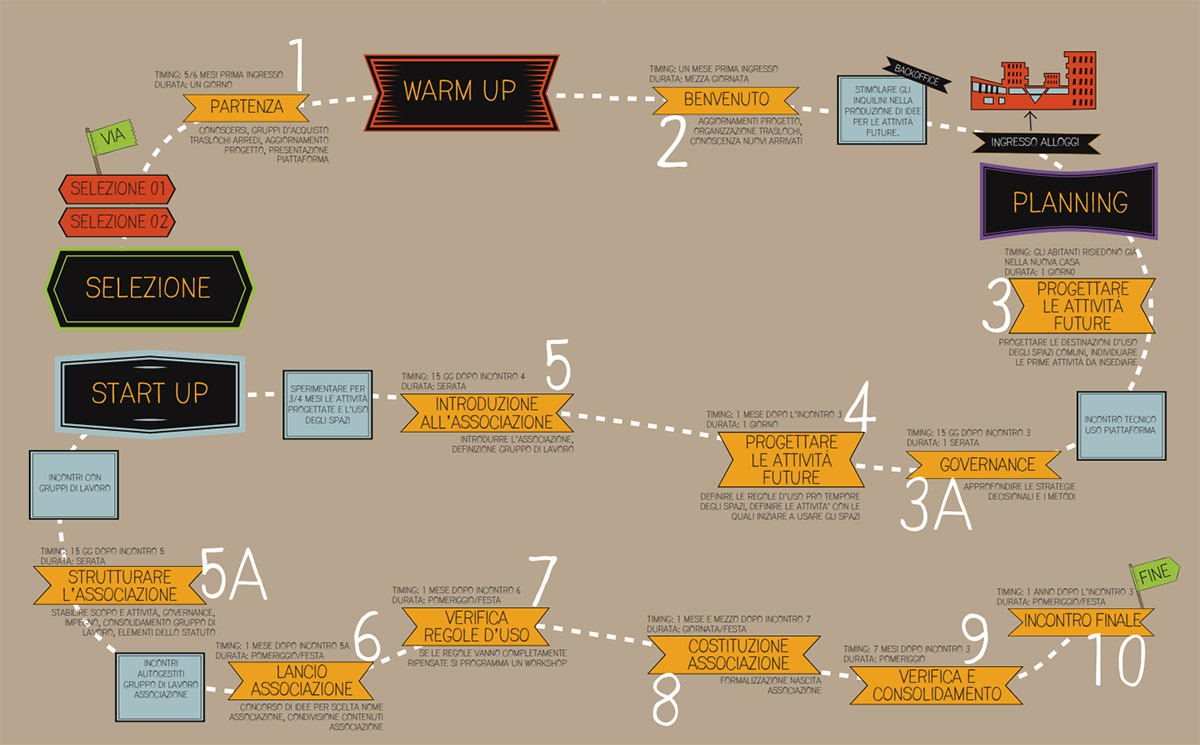

Sharing thus generates metaprojectual impact with social, cultural and economic growth of communities. A value that is measured "with an internal rating to value the contribution of the letter "S" of the ESG acronym," and that requires innovative collaborative tools. That is why platforms have been designed to manage projects and facilitate communication among tenants, as well as to structure the governance of processes. Tools that are aimed at starting and consolidating long-lived social infrastructures and that are technically configured as community start-ups. It is precisely this approach that has enabled FHS to obtain several international awards such as the "honorable mention of the XXVII Compasso d'Oro Award," as well as the "European Collaborative Housing Award 2017" with the Via Cenni building project.

Via Sarpi - FHS Project. Image © Barreca La Varra

Giordana passionately tells us that the outcomes of social housing projects tell good stories. The total renovation of the block between Sarpi, Bramante and Niccolini streets, with one of the buildings in the project already inaugurated on Oct. 22, is a testimony to this. The project by studio Barreca La Varra, which involves the construction of about 200 social housing apartments through demolition and reconstruction of existing building bodies, is an integral part of a virtuous program of the Ca Granda Fund of the Policlinico di Milano. "The renovated building complex will in fact house Milan's first Ronald House of the Ronald McDonald Foundation, dedicated to the hospitality of families with children being treated in the hospital." A program that has a truly beautiful story "because the funds from the acquisition will be used to self-finance the new Policlinico di Milano: a new public hospital with private money from the hospital foundation."

Via Sarpi - FHS Project. Image © Barreca La Varra

In Giordana's story, the architectural design of the social project thus feeds a global challenge that generates a sustainable finance "ripple effect" in accordance with Goal 11 of the UN SDGs, for "making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, durable and sustainable". Indeed, with Giordana Ferri's social housing, we move from theory to practice of ambitious and complex programs. Case studies for supporting urban regeneration policies, which can inspire not only new models of social housing, but also new guidelines for circular economy 2.0' housing. This is because Giordana's work has an open perimeter, and a vision that encompasses the opportunities for a new model of economy, culture and social development.

Read the full transcript of our interview with Giordana Ferri below:

Antonello Magliozzi: Giordana could you tell us about your background and professional history and how you came to be involved in social housing in your current role?

Giordana Ferri: The background comes from my history. I grew up in a family-owned architectural firm, always involved in the design of public housing and public works. Then I had my own architectural firm for about 15 years and continued to be involved in public works design. At that time, I started to collaborate with the architecture faculties of the University of Milan in the field of service design with Professor Ezio Manzini. Then, in the early 2000s, I started working in the first Italian co-housing company, and, from there, I became more specifically involved in housing forms other than traditional ones. At that time, I met Sergio Urbani of the Social Housing Foundation, who asked me to start working with him to realize a new idea of social housing through the economic instruments of the real estate fund. Thus, coming from a co-housing experience, I thought of introducing a collaborative model within rental housing through start-up forms. Based on this experience, I wrote two texts, a handbook on social housing design and a handbook on community start-ups. This was because with the Social Housing Foundation I did a lot of work on the study of housing typologies, and on defining design guidelines, for example, of open spaces, or the hierarchy of spaces beyond living space. This allowed me to deal with the architectural design of the social project, trying to understand and study what had been done in other countries, where social housing was more developed in terms of numbers. During these insights, I also found that our work had perhaps more detail in content, although it was less developed in terms of projects.

Antonello Magliozzi: What has happened over the past twenty years in the evolution of the concept of social housing? What distinguishes the social housing of today from that of the past?

Giordana Ferri: The social housing concept of providing rental solutions to meet the needs of large numbers has developed slowly. A slowness determined not only by economic aspects, but also by administrative ones. In Italy, implementation times are generally longer than in other countries because planning activities take so long, as do those related to building permits. In any case, similar to what has happened in other European countries, with FHS the concept of social housing that is based on the collaborative model has developed a lot in Italy. I could say that today, compared to the past Social Housing Foundation is trying to adopt a collaborative model at the neighborhood scale, not so much at the building scale. This is because the collaborative form at the building level is actually comparable to voluntary association forms at the neighborhood level, such as "social streets." This implies that common spaces within the building are not segregated, but are conceived as spaces available to the neighborhood. The same services found in social housing properties, are not just for residents, but available to the neighborhood.

Starting up Communities. Image © Fondazione Housing Sociale

Antonello Magliozzi: Giordana, how much does the collaborative project affect the housing project from an architectural point of view?

Giordana Ferri: There are many connections between the two types of projects. There are details that need to be considered. It is necessary for common spaces to be traversable and open. For example, entrances to buildings should always face inward, toward a common open space. If in a courtyard building the entrances were all outward, toward the street, people would never meet. Instead, in the semi-public spaces generated inside the buildings "people stay" and chat safely, children play independently. In addition, these spaces are also used a lot unintentionally. This depends a lot on the architecture, on the form of the master plan that has to create spaces that are protected, but at the same time open to the city.

Antonello Magliozzi: In projects you follow, what is the relationship between new features designed to facilitate collaboration and traditional housing types?

Giordana Ferri: In our social housing projects, traditional housing types, with optimized space appropriate for families, make up 70 percent of the total. The remaining space, from a mixite perspective, is allocated to other special types such as, for example, foyers: apartments for temporary sharing between families, so that the resident families themselves can seek a more stable future condition. Collaborative functions also include co-housing residences for the elderly, co-living units for young people, and studio housing for professionals, who hybridize living spaces with workspaces. The latter also represent an architectural opportunity in the logic of the master plan, with the advantage of a ground floor for professional activities, and a first floor for more private domestic life. Then, in addition to the aforementioned housing types, there are residential services for the third sector. These are rented to organizations that use them for specific social projects for the benefit of disabled people who decide to live on their own (dopodinoi project), or for new adults, mothers with children removed from the family, relatives of sick children, children's communities, etc. Usually such residential services make up 10 percent of the total apartments. Finally, other residential units are for public housing, and thus allocated according to municipal rules.

Antonello Magliozzi: What, on the other hand, are the non-residential services available to the buildings and the neighborhood?

Giordana Ferri: There are many of them. Usually there are services run by third-sector entities, which can be hybrids and contain commercial functions or cafeterias, which generate, among other things, job opportunities for the residents themselves. Then there are, as in the case of the Via Cenni complex in Milan, cultural centers that can become landmark elements at the urban level, not just the neighborhood level.

Antonello Magliozzi: In such projects that have a pronounced social value, can architectural quality also be pursued despite the possible presence of economic constraints?

Giordana Ferri: Yes, Social Housing Foundation aims to produce quality architectural works. Recognized architects usually design our interventions, and in some cases even famous ones such as Snohetta Studio, Barreca Lavarra, MAB, Botticini and others who produce architecture of a certain quality level. Yes, we have economic limitations, especially in the present period of energy crisis, but we try to carry out the projects in a way that always preserves the overall quality of the interventions.

Antonello Magliozzi: Could you tell us about any specific projects? Are social housing interventions mostly referring to new master plans or functional conversions of existing buildings?

Giordana Ferri: I could mention a recently finished project at the end of Via Ripamonti in Milan called 5Square, which was designed by the Barreca Lavarra studio. On that site, there were five blocks of abandoned and unfinished Italian Post Office buildings that had only the concrete structure. We were able to buy those buildings and turn them into social housing, creating a project including various neighborhood services and new urban destinations precisely in an area that had a strong lack. Then I can mention a work done with another real estate fund with which we did three interventions in the Paolo Sarpi area also in Milan. A program of interventions that has a particularly good story because of the general financial purpose, and because the acquisition funds will be used to self-finance the new Milan Polyclinic: a new public hospital with private money from the hospital foundation. Of the three buildings in Paolo Sarpi, we have completed one that includes 200 apartments, preserving the facade as it is constrained, and redoing all the interiors. The other two buildings will be treated with conservative restoration work. Again, the Barreca Lavarra studio carried out the project. Then another intervention I can mention is our "historic" one: via Cenni building, the first intervention done in Milan, which also includes the "urban cultural sea" center. A nine-story high wooden building that has the record of being among the tallest made of x-lam. There are then several others that we have included within our own map of Milan's social housing.

Via Cenni activities. Image © Fondazione Housing Sociale

Antonello Magliozzi: With reference to the subject of sustainability, which is relevant today for every type of project, and, I might say, even more so for projects that have inclusiveness as a priority, what goals do you set?

Giordana Ferri: The focus over sustainability is utmost. It is a key parameter of our interventions. Energy saving, for example, is one of the main goals we set. ESG parameters must be followed in investments and, very often, the results are reported with a GRESB scoring. In some cases in our projects, we have also included certification according to the LEED protocol. Then we also have social impact meters, with an internal evaluation rating to specifically value the contribution of the letter S of the ESG acronym.

Antonello Magliozzi: How, on the other hand, do you measure the environmental impact of buildings operational phase? Do you provide systems for measuring and reporting on environmental parameters?

Giordana Ferri: In many cases, buildings have IOT sensors and an app that tenants can use, so they can check what their consumptions are and, at the same time, they may participate to sharing activities. In fact, the app has a dashboard with two functions: one for community, for managing the agenda of shared spaces, and then another for monitoring consumption that sometimes ties in with playful-competitive activities for consumption reduction. An app that gives alerts in case you consume too much and gives many tips to the community.

Antonello Magliozzi: What awards and recognition has Social Housing Foundation acquired over time?

Giordana Ferri: Over time, we have acquired several awards. I could mention the one taken recently in Seoul at the service design festival with a special mention and a Golden Compass. We were aslo awarded the "European Collaborative Housing Award 2017" with the Via Cenni building project.

Top image courtesy of FHS.

All images courtesy of FHS unless otherwise stated.

1. The link should be copied-pasted on Google Chrome (http://download.pearson.it/archivio/materiali/3507_1475654561.pdf).

2. The link should be copied-pasted on Google Chrome (http://download.pearson.it/archivio/materiali/3011_1482398324.pdf).