Submitted by Momoh Kakulatombo

Tracing Colonial Space in Trans-Nzoia: Imprint of the Duke of Manchester

Kenya Architecture News - Jun 26, 2018 - 06:42 22434 views

In Western Kenya, a Colonial settler home slowly ages against low rolling hills. It is here that 72 years ago the 10th Duke of Manchester built a farmhouse for himself in Trans-Nzoia County.

It is late summer time in Western Kenya, a marked time as the end of the first rains confirm and complement farmers activities. Arterial marram roads through the surrounding farmlands show stamps of footprints and tire treads, showing the slow going vitality of rural Trans-Nzoia. Many people who live here plant long and short cycle produce at home. Living life here as an inhabitant, you’re very likely to buy vegetables from a neighbor when the need arises.

Moi’s bridge, the nearest largest town, was once called Hoey’s Bridge. It was first named after a renowned colonial settler in the region then became Moi’s Bridge, as it is now known, after Kenya’s independence in 1964. The change in name was an act manifesting the sweeping change of attitude among indigenous Kenyans regarding their hard fought gained independence. This phenomenon is not unique to Kenya. There are also instances of this happening in others countries under colonial rule across Africa. The act of renaming is a common change in former Colonial states, including the Kingdom of eSwatini (formerly Swaziland).

Moi’s Bridge is a bustling town between Kitale and Eldoret in Trans-Nzoia County, Western Kenya. It hosts Kenya’s largest Maize Depot, a seasonal destination for many farmers in Eastern Africa. Indeed, farming is an activity that supports rural livelihoods of people living in its environs.

The former Colonial Settler’s estate is a group of single-story buildings that sit on a carved elevation on a hill. The axis of the main building sits north-south. Approaching from the East, a verandah opens onto an interior space. Inside, this space leads to a dining room adjacent to the living room, together making the largest space in the house. It is a brick-wall structure concealed in protective cement that has grown black-green with age.

Top image © Wikipedia. Bottom Image © Converse Africa

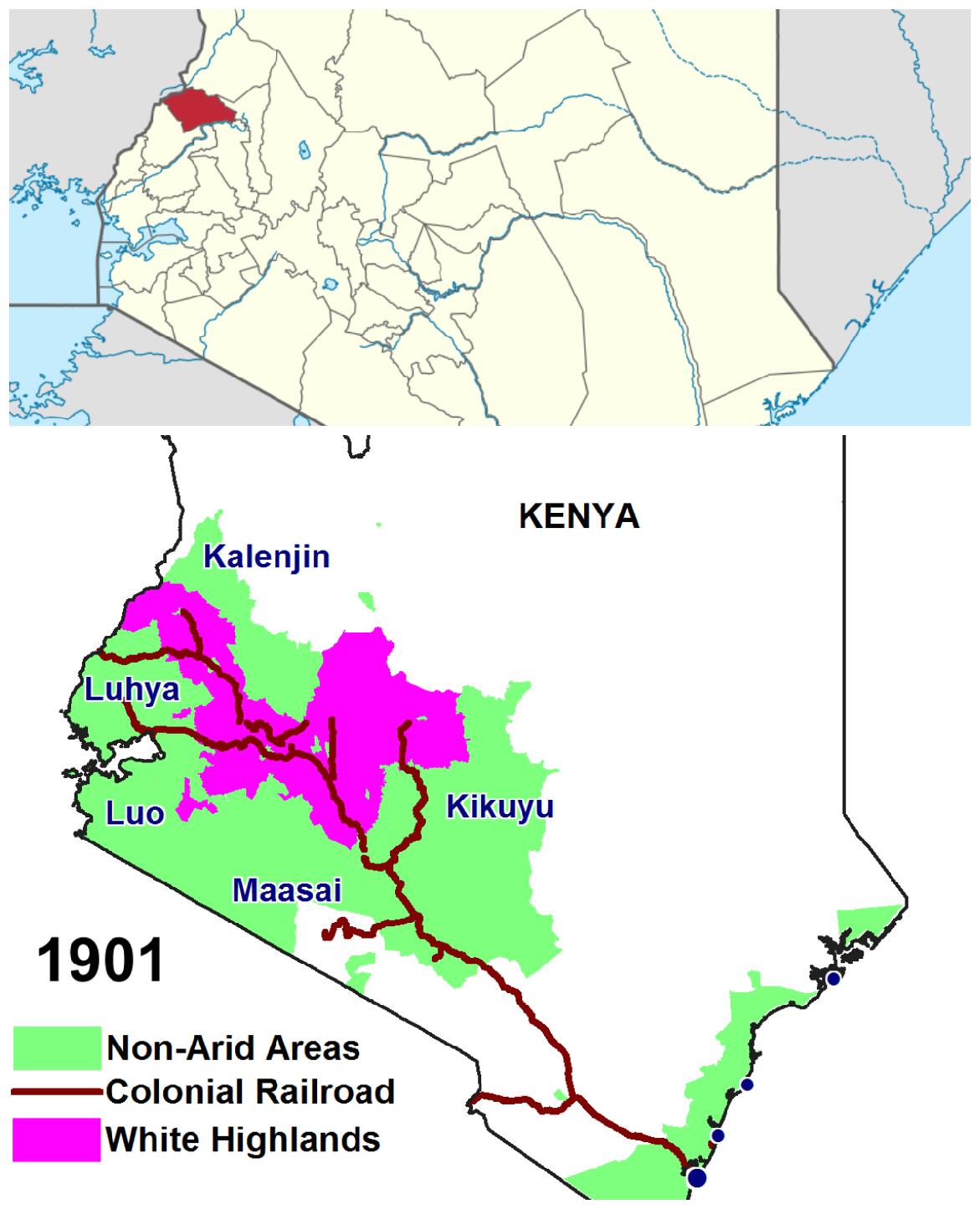

Hoey’s Bridge was a part of a region called the White Highlands. According to a Wikipedia page, "this geographical locale covered 25% of Kenya’s good (arable) land," was expropriated from the indigenous people, and given toward the cause of a British settler community that would survive through the means of an agriculture industry. This opportunity for the colonists was self-legitimized in 1905 when the East African Protectorate existed (1885-1920). To this end, "the British Immigration granted British European settlers 999-year leases to encourage further British colonization."

"The main influx of European Settlement in Trans-Nzoia came after 1918 when the discharged Soldier Settlement Scheme was implemented. Many of the new settlers were of British origin and hailed from lower middle class backgrounds. Most had no previous agricultural experience. Over the next few years as more land was brought under the plough and crop production increased, Trans-Nzoia became a major European farming district," according to a Master's Thesis by Joseph Nabwera.

The succeeding stage of colonism was the establishment of the Kenya Colony in 1920, by which time about 10,000 British people had settled in the White Highlands’ area. Up until Kenya’s independence, the colonists economic, social and cultural policies systematically disadvantaged and abused the human rights of indigenous Kenyans. The majority had little choice but to live on African reserves or work as squatters on settler farms for survival.

Mentioned in a Wikipedia page, "Alexander Montagu moved to Kenya in 1946, and become the 10th Duke of Manchester in 1947," upon which he entered a political class known as the Peerage of Great Britain. "He had just left serving the Royal Navy after the Second World War had ended. In Kenya he farmed and estate of 10,000 acres." As a former serviceman of the Royal Navy, it is likely that the Duke acquired land as a part of the aforementioned British Immigration scheme. In the context of the 1918 Resident native Ordinance, Kenyans who chose to be squatters were effectively made peasants. It is likely that Mr. Montagu farmed by these means. Simultaneously as one mode of life imposed itself, several particular African cultures either adapted to or rebelled against the forceful change imposed on them.

The wide Eastern face of the building looks to the distant Cherang’any hills. Every bright morning, rays of sunlight would have fallen on the house, washing it through with the aura of African Frontier, an sentiment that had currency with many settlers and may have considerably inspired the design. The frontier is an idea that captured the minds and hearts of the European Settlers in Kenya, including the author Karen Blixen.

The Duke of Manchester is one of the existing historic buildings within the ‘white highlands creating what might be called a 'White Highlands Architecture.' These are places are where cultures collided and changed one another. As a reminder of our past, such places are in fact heritage assets that would benefit local Kenyans to take care of. Trans-Nzoia County’s future planning and development should take the potential of this building into consideration, as a part of the fabric of their unique built environment. The building is currently privately owned.

The conservation of our heritage is important because it is another way of knowing ourselves – and in the case of the built environment, how many people made a place come into being. In 2016, a publication entitled “Conservation of Natural and Cultural Heritage in Kenya edited by Anne-Marie Deisser and Mugwima Njuguna” detailed leading work done towards the conservation of heritage in Kenya. In the text, the contributing authors highlighted a definition of culture (from the Charter for African Cultural Renaissance) which states that: “Culture should be regarded as the set of distinctive linguistic, spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of the society or a social group, and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs; That all cultures emanate from the societies, communities, groups and individuals and that any African cultural policy should of necessity enable peoples to evolve for increased responsibility in its development.” Indeed, the Duke of Manchester rests within Kenya’s cultural history and should be conserved as a necessary part of Kenya’s heritage.

The ways in which conservation link with technology continue to be explored as sustainable alternatives to heritage conservation. This year, the Museum of British Colonialism have embarked on a collaborative journey to retell the story of the Mau Mau Rebellion in an upcoming exhibition in Kenya. For the exhibition, the team of researchers are underway in creating a 3D model of the historical internment camps where Kenyans were violated and denied their human rights under British rule.

The work of preserving the Duke of Manchester is deeply important to reconstructing the history of the White Highlands. Narrating our own stories depends on the ability and willingness we possess to preserve our history. Creating spaces to live in that celebrate a shared history enable us to enjoy learning from history and to go beyond it.

All images courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.