Submitted by

Exclusive: "Architects Should Protect As Much Space As Possible For The Public" Says Elizabeth Diller

teaserd-6-.jpg Architecture News - Aug 11, 2018 - 04:53 5704 views

"The role of the architect is to protect as much space as possible for the public. If I had it my way, I would just turn every ground floor of every building over to the public. That would be fantastic in the democratization of space," says New Yorker architect and educator Elizabeth Diller, co-founder of Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R).

The issue of publicness is very, very important in every city, according to the acclaimed architect. "We live in a time of privitization with less public space in our cities," Diller told World Architecture Community in an exclusive interview at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Elizabeth Diller founded New York-based firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) with her partner Ricardo Scofidio in 1981. She is the only woman architect leading the firm DS+R's projects, along with Ricardo Scofidio, Charles Renfro and Benjamin Gilmartin.

The Broad Museum on Grand Avenue in downtown Los Angeles. Image © Iwan Baan

Diller, 63, was recently named as the world’s most influential architect by TIME Magazine, and she was the only woman architect listed among the most influential people under the "titans" category, including Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Oprah Winfrey, and Roger Federer.

Although DS+R is best known for its cultural projects completed in different parts of the world, the office actually describes itself as an "interdisciplinary" studio, as the office's projects extensively span the fields of architecture, urban design, installations, art, multi-media performance, digital media, and print.

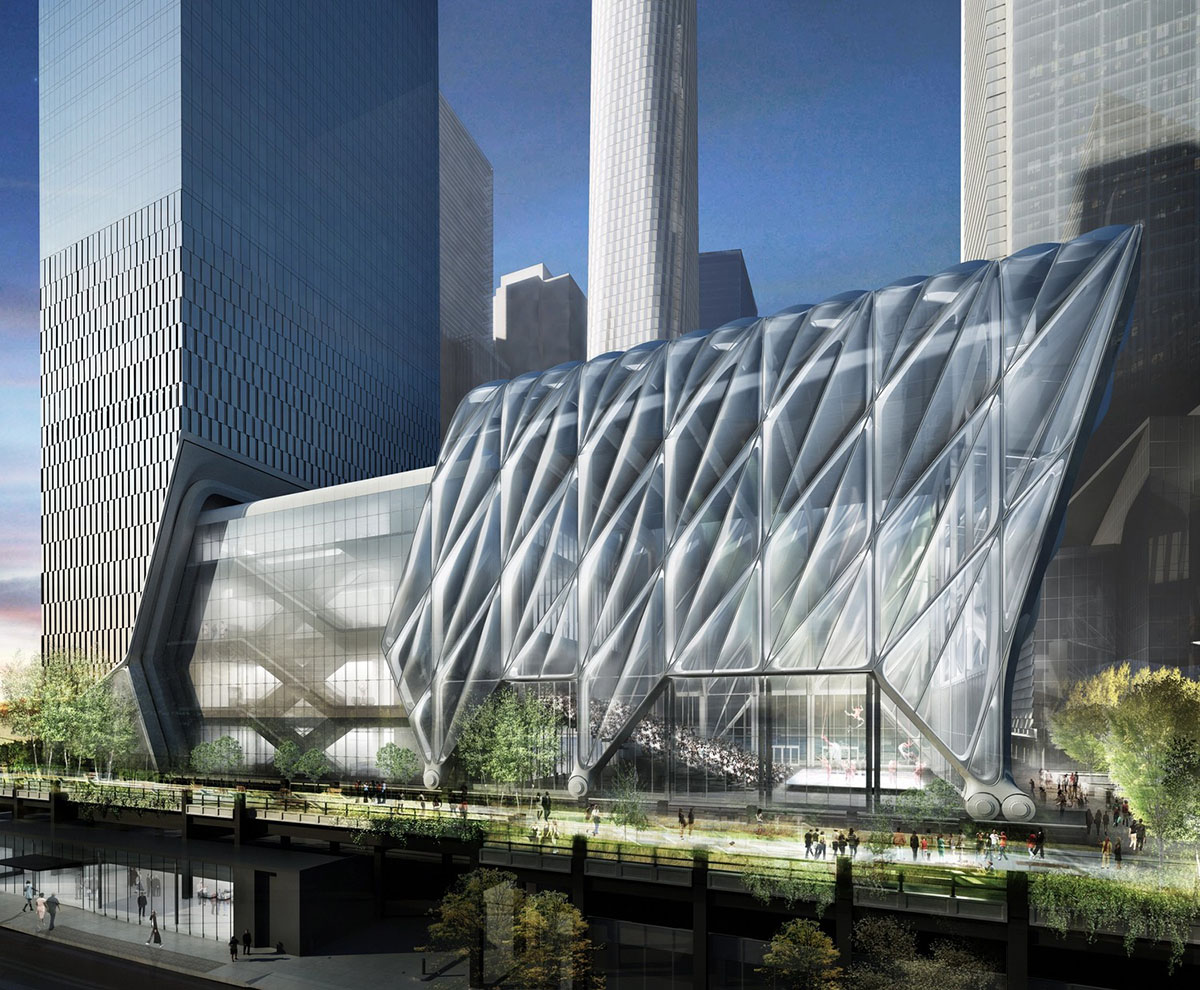

The Shed is currently under construction in New York. Image courtesy of DS+R

DS+R's projects don't follow a particular architectural language, while adding flexibility, some sort of complexity, new materiality, new media interface and the dominance of public space throughout the form. The studio's utter form is derived from the variable inputs of the context and the DNA of the program, which makes all DS+R's buildings fluxional and charming. But, the studio's design approach is also based on adding a new architectural component and playing with the existing program of the project brief, according to Diller.

"We need to find new kinds of equations between public and private," said Diller. "And, every space doesn't have to be labelled," she added.

"But, to have un-programmed space, I strongly believe that you have to put in forcefully un-programmed space."

"Everyone is so concerned about maximizing efficiency with every square foot and every square meter to cost a specified amount of money. Un-programmed space can mistaken as wasteful excess because its not quantifiable, but it’s just as necessary as air," Diller continued.

DS+R's High Line in New York completed in 2014. Image © Iwan Baan

Diller Scofidio + Renfro is best known with the High Line Park in New York - the transformation of the former industrial rail infrastructure into a 1.5 mile-long public park, the Broad Art Museum in Los Angeles completed in 2015, which was aimed to urbanise the building for visitors coming directly from the street, and the transformation of Lincoln Center’s half-century-old performing arts campus. DS+R is currently working on two significant projects in New York; the Shed, a new flexible cultural venue which will open next year, and the major expansion of MoMA in which the first phase of the overhaul opened last year.

Moreover, DS+R's Museum of Image and Sound, a zig zag-shaped museum defines a new type of 'publicness' via its fluid staircases, still under construction in Rio de Janeiro. The firm is also working on a new Centre for Music in London, near the Barbican.

Columbia University Medical Center’s (CUMC) Roy and Diana Vagelos Education Center at Columbia University, New York. Image © Iwan Baan

In addition, Diller also led three installations in May 2018: the Costume Institute’s "Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination" exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and two installations at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale: one at the US Pavilion and another at the Vagelos Education Center at the Arsenale.

Last but not least, the studio recently won an international competition to design a new dynamic art space on Adelaide’s celebrated North Terrace, in collaboration with Australian architecture firm Woods Bagot. DS+R's portfolio includes many more cultural projects, even if Diller doesn't accept herself as a "specialist" on the cultural projects. She says that her studio has a lot of formal freedom, and that's why, DS+R's projects look different.

From MET's Heavenly Bodies exhibition. The Met Cloisters: Fuentidueña Chapel. Image © Floto + Warner

Although she was trained as an architect in the 70s, Diller's artistic ability helps her to transform buildings into an artistic form - not methodologically, but instinctively. The building already takes a performative embodiment in every aspect, to make the buildings, open, welcoming and really usable for the public. And, the Broad Museum already proved it.

Diller was born in Poland, she received her architectural degree from the Cooper Union School of Architecture in 1979. She originally began her studies at Cooper Union in art but she took an architecture class because she was interested in multi-disciplinary fields such as theatre, arts, installations, performance art, which later would become central to her work with Ricardo Scofidio.

DS+R's Partners: Charles Renfro, Elizabeth Diller, Ricardo Scofidio and Benjamin Gilmartin. Image © Geordie Wood

In 1999, Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio were the first architects to be awarded the MacArthur Foundation's "Genius" Grant, given in the field of architecture. Currently, Diller is a Professor of Architecture at Princeton University and a Visiting Professor at the Bartlett School of Architecture. Elizabeth is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).

In the full transcript of this exclusive interview, Diller talks about Freespace, the installation of the Vagelos Education Center at the Arsenale, the lack of public space, the design process of the Broad Art Museum and the design philosophy of the studio.

You may find the full transcript of our interview with Elizabeth Diller below:

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Let’s start with theme of the Venice Architecture Biennale; this year’s theme is Freespace. Although I don’t know if you already finished visiting the whole exhibition, but, I would like to start by asking how you found the exhibition in general? – I mean, could you please evaluate the works exhibited here, and their response to the theme of the Biennale and the general techniques of presentation? I’m asking this because in previous Venice Biennale, we have seen so many projects that were made of hand-crafted forms that refer to traditions, or some sort of a mixture techniques.

Elizabeth Diller: I hesitate to respond because I’ve spent most of my time fine tuning the studio’s two installations and participating in some of the ceremonies, so I haven’t really spent enough time with the other installations. But from my point of view, I can say, participating in the exhibition for this theme is interesting because the theme was really, really broad. Previously, we have worked with other curators, who were interested in more theoretical and more discursive shows, but the theme of Freespace seems to be very oriented to built projects.

The curators approached us with an interest in the Roy and Diana Vagelos Education Center and we wanted to explore techniques for transplanting and translating the building’s story off-site, into an exhibition space like this. Besides producing a large scale model, we directed a film that interprets the building’s study cascade- a new manifestation of the project’s driving concept.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Yes, you are right because the theme is quite architectural and broad, it makes their individual interpretation quite difficult. I feel there are many responses that we need to take out, especially this year, in many layers...

The Museum of Image and Sound's protruding facade presents a new complexity with its flowing public staircases in Rio de Janeiro. Image courtesy of DS+R

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Let’s focus on the theme in detail then; What does "freespace" mean to you as an architect, in different types of projects? And/Or, what is DS+R’s general manifesto to create a "freespace" in its projects - I mean, is it really something that should be designed for "all", or, should it create “unexpected situations”, or “richness” as mentioned in this year’s manifesto?

Elizabeth Diller: I guess, I can answer your question as a New Yorker where real estate is bought, flipped and sold all the time. We live in a time of privitization with less public space in our cities.

More importantly, it is very much controlled by real estate developers. So, I feel very strongly that the role of the architect is to protect as much space as possible for the public. If I had it my way, I would just turn every ground floor of every building over to the public. That would be fantastic in the democratization of space.

"If I had it my way, I would just turn every ground floor of every building over to the public. That would be fantastic in the democratization of space."

We need to find new kinds of equations between public and private. Freespace, for me in a way, starts there. It starts with the very practical issue of asking, who owns property? What qualifies for free space? And free for whom? There are many ways of translating that theme in all projects we work.

In general, we’ve been taught to consider a “free plan” or “free section” in architecture school. It’s a method to make space more liquid, more accessible, and more efficient. I believe in efficiency because it has a knock down effect of generating more volume of space. It’s a purely disciplinary response that contributes to Freespace. I think, another form of freespace is a more liberated program, rather than designating every space with a set function.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Yes, to change their functionality, maybe, apart from its labelled name.

Elizabeth Diller: Yes, it's very specifically slotted. For example, when we design a building like a museum or some cultural or educational building, every space has to be labelled. It always has a name - it always has a reason and a purpose. But, I strongly believe that you have to put in forcefully "un-programmed space".

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Like, by forcing your client?

Elizabeth Diller: Yes, in most cases it requires convincing the client of the merits of space that is ultimately flexible, and constantly changing. Everyone is so concerned about maximizing efficiency with every square foot and every square meter to cost a specified amount of money. Un-programmed space can mistaken as wasteful excess because its not quantifiable, but it’s just as necessary as air.

The Museum of Image and Sound is currently under construction on Copacabana Beach. The building is set to open before the end of 2018. Image courtesy of DS+R

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: DS+R is exhibiting the Vagelos Education Center at the Arsenale, which was opened two years ago in New York. What does your project tell about the theme of the Biennale directly or indirectly? Why did you choose that project?

Elizabeth Diller: Shelly and Yvonne actually selected the project and it was the basis of our invitation. We were very happy to show it.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: It’s quite atypical and doesn’t look like any other tower.

Elizabeth Diller: Medical buildings are usually characterized by low-slung ceilings, densly-packed programs, and double loaded corridors. But the given site for this project had a very narrow footprint and a tapered zoning envelope that allows us to build 14 stories high.

We saw this narrow footprint as an opportunity to create spaces with different attributes - some of them are big or small, some open or closed, or some facing South or North, and so forth. We also thought this diversity of spaces would be well suited for the paradigm shift that was occuring in medical education from passive, lecture-based instruction to team-based problem solving. And we wanted people to be able to move fluidly from level to level. We typically talk about flexibility in just neutral spaces, like Freeplan, or infrastructure that you can put in anywhere. But, here its about circulation and the accessibility of choosing a space that specifically responds to your needs.

The Vagelos Education Center is exhibited at the Arsenale with a long film. "A two-channel video installation captures this productive inefficiency as a day in the life of a student, a side by side observation of the Study Cascade sharing and engaging with people (...) long after the architect has left the scene". Image © Andrea Avezzù, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: That’s the challenge, I guess. Basically, to create a complete contrast, I mean, if we think about any typical Research Centers and Education Centers, they are very monolithic and serious blocks and I see this building as very different. The first impression it gave to me is that this building could only be a vertical Art Museum. I did not think it could be an academic building.

Elizabeth Diller: True. Since the building opened, I heard applications increased, and the program was ranked in the top 10 among medical schools in the United States. I think this is partly due to the facility and student body being really excited about the building. It enables an interesting debate about medical education that was unfolding during the competition: Should students be taught with cadavers in an anatomy lab? Or should they be taught with robotic bodies in a simulation room? It was incredibly interesting to hear the debate from the faculty. Teaching through the anatomy lab meant you could foster empathy for patients by learning to operate with a human body, though some argued there was nothing at stake since the subject was no long alive. Teaching with the simulation room introduced a high level of precision through robotic training that uses wires to simulate a pulse, a heartbeat and a temperature. In the end, the building houses both types of facilities. The building is half-tech but it's also very physical.

The Vagelos Education Center is exhibited at the Arsenale with a long film. Image © Andrea Avezzù, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: I see the DS+R’s projects emerge as an intersection of Art and Architecture – like an urban sculpture that has some sort of a “theatrical approach”, that forces someone to discover something new, media or space in the building. I think, from an architectural perspective, today’s architecture doesn’t follow or focus on any specialization anymore. What I mean is that architects nowadays feel they should design everything – starting from urban planning to a product design. Do you agree with this trend, and where does DS+R's design philosophy stand on this? In other words, should architects be interdisciplinary?

Elizabeth Diller: I live in an interdisciplinary world, and for me architecture is just one trajectory of the work. Our studio also designs performances, independent artworks, digital projects and so forth. I'm also an educator. I think, there are maybe two answers: from one point of view, architect design buildings and design in an urban context. But, on other hand, architects have to be generalists that provide a common platform for working with specialists.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: What do you mean by generalist?

Elizabeth Diller: By generalist, I mean you have a vision and you're bringing everything together, like being a movie director. But you have also a vision about the cinematography of that vision, the sound, the editing, with every specialist and controlling position. So, on the one hand, I believe in craft of some different types of people that contribute to architecture, but by working very directly with them. I think architecture has to cover everything. To be an architect is to be able to work through issues like an engineer and a landscape designer and audiovisual (AV) specialist etc, because you're working directly with them. You're not just handing over the work and your vision to them.

"By generalist, I mean you have a vision and you're bringing everything together, like being a movie director."

However, I don't think that every architect should work in multiple disciplines, because only a few actually have a talent or feel in other disciplines. For DS+R’s projects, I can say that we don’t work in conventional ways in general. For instance, the US Pavilion is a digital project and it has a broader political theme. It's not at all like a building project for Freespace, and that explains why we insisted on doing this video of the building in use, because we didn’t just want to make the model. I think, there are multiple disciplines all the time and that's the definition of our studio. It's not really just a traditional architecture-that would bore me. It's really comprehensive and it's the intersection of not only the visual arts and performing arts, but also the intersection with policy, economics, and thinking process. It serves to expand the architect’s agency to be able to impact programs. It's just about having an effect, and we were able, in New York, to really do some major things.

For example, the Shed (which opening next year) wasn’t just architectural. It is representing the idea before its institutional position, but it also combines both an architectural and an institutional idea. I don't want to live in a world where borders take place. It's kind of just being involved in the way that our world is complex.

DS+R's Zaryadye Park completed in 2017 in Moskva, Russia. Image © Iwan Baan

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: DS+R has been designing major cultural buildings in different parts of the World – and I don’t want to describe you as “a specialist” on cultural buildings. But there is some specific input that you seem to follow in your designs for cultural buildings: like reflecting the building itself as a new media or new material. They look very far from a serious or monolithic appearance; they appear more intriguing or chameleon-like structures. In your mind, what is the difference between designing cultural buildings today and designing cultural buildings 20 years ago? What do the users really want? What did change in architects’ or even clients' roles?

Elizabeth Diller: I should state that architecture itself is a cultural discipline and when you think about a space for art, architecture has a role in making space for art because it contributes to the culture of architecture along the way. And, it's the same thing for a music center or other kind of cultural projects, in which we try to advance in our own discipline.

"The culture of architecture should be thought not by being neutral, but by creating a kind of a major response - but also by supporting the form."

So, the culture of architecture should be thought not by being neutral, but by creating a kind of a major response - but also by supporting the form. When we think about the discussions on the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, it was like: what's more important, the Building or the Museum? The building is part of the museum as the first collectible item. So, there was this argument and then the argument has expired.

I believe there’s a false distinction between architecture supporting a cultural function or architecture becoming the protagonist. I think it has to do both. It has to present that form. It has to say something publicly about space. But more importantly, in terms of opening up the general discussion, it’s also important what people and cultural leaders are thinking and why we see more cultural institutions and architects are attached to them. I think the cynical response is that maybe architects have more credibility today than they used to before. They bring more value to a project in terms of cachet. But that's the cynical view. There are many architects thinking about the interface between the public and the cultural space. And this is very characteristic of our projects.

We create a kind of a thick interface between that municipal space and the space where the concert or exhibition happens. That space is not just the wall, not just a door; it's a big frame. It's a layered space where ideas are exchanged, that is largely porous and the public is really invited. The public doesn't always make it to the next part, but is halfway there. So, I believe in a building that has audiences for culture. Currently, we’re doing a concert hall for the Barbican and a couple of museums. But, public space is always very, very important to us. Even if you don't go beyond, you’re still engaged with a population that is decided to slow down, maybe to have an intellectual exchange.

Lincoln Center in New York completed in 2010. The studio redesigned public spaces of the building, including the Central Plaza, the North Plaza, the conversion of 65th Street from a service corridor into a new central spine, the transformation of three blocks of Lincoln Center’s frontage at Columbus Avenue and eventually, Damrosch Park. Image courtesy of DS+R

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Let’s be more specific on cultural buildings. If we go back to the design of the Broad museum, what is the reason that the Broad in LA is so prominent among other buildings you designed? And, why do so many people love this building, apart from its unique and particular form or biomorphic skin? From your own point of view, what were the design decisions that forced you to design that specific form?

Elizabeth Diller: The challenge was that it is located in the main street of Downtown Los Angeles, on Grand Avenue. It’s also a private collection the Broad Foundation was making public. In addition, it was primarily an archive when we started it, which means that it was all these paintings and sculptures stored, and there was a very small exhibition space. So there was a weak point between the main street of downtown and Los Angeles, which is really sad for the city itself, and there's a desire to urbanize it. So this building could really help, but now there would be an archive there. So we had a dilemma and we specifically designed the building to be very efficient so that we could have more spaces for exhibition. Moreover, we designed the building to be porous. Light comes in from all surfaces top and sides and it was, sort of, lifted from the ground at the corner, so that the public could come from the street. The museum is typically a hermetic building, but this is intended to be a porous building in every way. And it's working! We managed to get a huge footprint of column free exhibition space with natural light; it almost measures 65 to 70 meters in both directions without columns.

The museum is free, and there's no information desk. There's no place of authority to come from the street. For instance, you just go up the escalator, you go either to an exhibition space on the ground floor, or upstairs and then you see the archive - the archive floats in the middle. You see it immediately, you are under it, and you go through it, or you're on top of it; then you could find your way inside of it, and see through different directions. So, I think that it's just simple building and people understand it. And it has a kind of form that is maybe unfamiliar. I think it is very welcoming and people feel comfortable there.

I'm really happy, because it has a couple of distinctions. It has the youngest demographic in the country. The typical age of museum-goers is between late 30s to mid 40s but here, the demography shows visitors are of a younger generation in their 20s to 30s. It also has the most diverse audience. That's really interesting and very important, as how to get an audience of many populations that are not your typical museum goers. Sometimes students and young people go there, because they're interested in getting inspired. And there are people who are choosing to go to the building, and choosing to go to the collection, but they don't necessarily really know much about art. It's really, really interesting because there are a lot of people that come back, and come back with their families, and that's also about the younger people and the folks that are drawn to it. So I'm not really sure, I think that people like the building, and there are many, many things in the collection. That is really great, but there's some kind of a vibe there; so I can't exactly figure it out, but it's working.

In the Broad Museum: The vault stores the portions of the collection not only to display in the galleries or on loaned collections, but DS+R provided viewing windows so that the visitors can get a sense of the intensive depth of the collection and peer right into the storage holding. Image © Iwan Baan

Berrin Chatzi Chousein: Do you believe that you have a specific style among other architects?

Elizabeth Diller: We’re not so interested in that. I think of every project as an opportunity to think about program. They’ve governed by the cross-section of our brains, the obsession of the moment, and agendas, old agendas that have never been finished... And you bring all that stuff to every project. For us, it's not a formal agenda, it's really maybe a cultural and social one, that we are interested in. We have a lot of formal freedom and our projects look different. We really like that, but that might be a problem for clients, because they don't know what it's going to look like. The buildings are developed depending on the context, the time, the program, even the client; they are independently inspired and it's a unique set of circumstances.

(-end of transcript)

Top image: Elizabeth Diller. Image © Geordie Wood