Submitted by Antonello Magliozzi

Max Moruzzi on “how 3d printing can make materials to speak”

Italy Architecture News - Nov 25, 2020 - 15:08 5612 views

"The process of 3D printing is innovative only if it considers the vocation of geometries and numbers at all levels, only if it makes the construction materials speak through the physical and chemical integration of the various components," says Max Moruzzi in an exclusive interview. A sentence that summarizes the vision of one of the pioneers of 3d printing, an idea that arises from the author's specialist and holistic competences and which hints at specific potentialities not yet expressed. Max is not an architect, but he has clear ideas about what the architecture of our cities should be like. He is an Italian Aerospace Engineer born in Emilia Romagna with an extensive 15+ year career as Lead Scientist and Business Innovator in various fields such as “Living Materials” and Disruptive Manufacturing Process Automation, with a deep experience in the Business-Technology interface. He is now Head of Development cognitive Engineer at Augmenta AI.

Portrait of Max Moruzzi. Image © Max Moruzzi

He is a disruptive engineer with an aptitude for research and innovation, but at the same time he is also a curious dreamer who has pushed himself to work abroad to start projects never done before. Max Moruzzi has in fact indulged a passion for numbers and geometries that he had as a boy and, thanks to his studies at the Polytechnic of Milan, he investigated the potential of new languages of science as well as the concepts of "digital twin" ante litteram . In 2002 he moved to Illinois, United States, to develop a research project on robotics systems and production of innovative materials. He worked on the Dreamliner 787 project, the project that later revolutionized the Aerospace industry. "A new concept of aircraft, where the revolutionizing shape identified by Boeing had to be created with robotics and artificial intelligence through sustainable materials, such as innovative materials (i.e. carbon fiber) that had to last over time." He thus helped to change the way in which it was always built in the Aerospace, moving from a technology that used an isotropic material such as aluminum to another that instead uses plastic, an anisotropic material. An aircraft built with a 3D printing process, or as better defined by Max Moruzzi "an automated process of layering of composite materials, or additive manufacturing, which has then contaminated other sectors such as automotive and construction".

Max Moruzzi at work on his 3d printer. Image © Autodesk

The topic of 3d printing is very current today, but most of the time it is only seen as a system that uses artificial intelligence to build something layer by layer. Actually according to Max Moruzzi: "additive manufacturing to be truly innovative must provide for a new mental process of aggregation of works phases, with an intelligent holistic management of process parameters and geometries according to the physical-mechanical properties of the materials." In this sense, today 3d printing processes have unexpressed potential and do not effectively develop the concepts of sustainability and freedom of forms. This happens due to the permanence of various barriers that limit the growth and diffusion of a new technological thought. Barriers that depend on “a conservatism of politics and markets, where institutions remain passive with respect to the introduction of specific standards for the certification of materials, where many manufacturing companies, rather than favor new developments, remain focused on already consolidated processes." A not indifferent cultural gap that according to Max's vision could only be bridged "with an educational action and, thanks to the artificial intelligence itself, also through "self-training" tools.”

Max Moruzzi at FMIA2019 via Youtube © Forma Mentis

But what does Max Moruzzi actually propose to bridge this cultural gap? He proposes a new AI (Artificial Intelligence) driven 3d printer: a project that arises from the collaboration with an Italian manufacturing company in the Veneto region, Breton SpA, a company that has historically always made machine tools and that today feels the need to invest in innovation. A 3d printer that will be ready for the this Christmas period and that will have the distinction of being the largest ever made in Europe. A machine that will allow us to build "scientific prototypes and demonstrations with the intent to educate and remove the biggest obstacle to the development of 3D printing technology". A project that thus wants to create "an educational, qualifying and engaging tool". And what will be the prototypes produced by this new 3d printer? A "smart façade”, a facade that, as the author claims: "has no limits of shape and, of materials - for example, it can include the use of recycled plastics - and “living materials” to be the "alive" façade ever made. A prototype designed to add and integrate different materials, including conductive ones, in order to make the facade itself work like a battery ". A living façade "also means that the characterization of its shapes can count on the use of specific materials that actively contribute to cleaning the air, thus making the building itself as a large lung".

New 3d printer rendering image, Breton product. Image © Augmenta AI

It is no coincidence that this prototype refers precisely to architecture and buildings. Max Moruzzi sees in architecture something that belongs to him, like his dress, this is why he questions about the future of this discipline. He thinks that "often many buildings are already old when they are finished" and that to innovate them "one could instead inject materials and life into the architecture itself". Thus he sees the real challenge of 3d printing in the architecture sector as it belongs to the ecosystem of people.

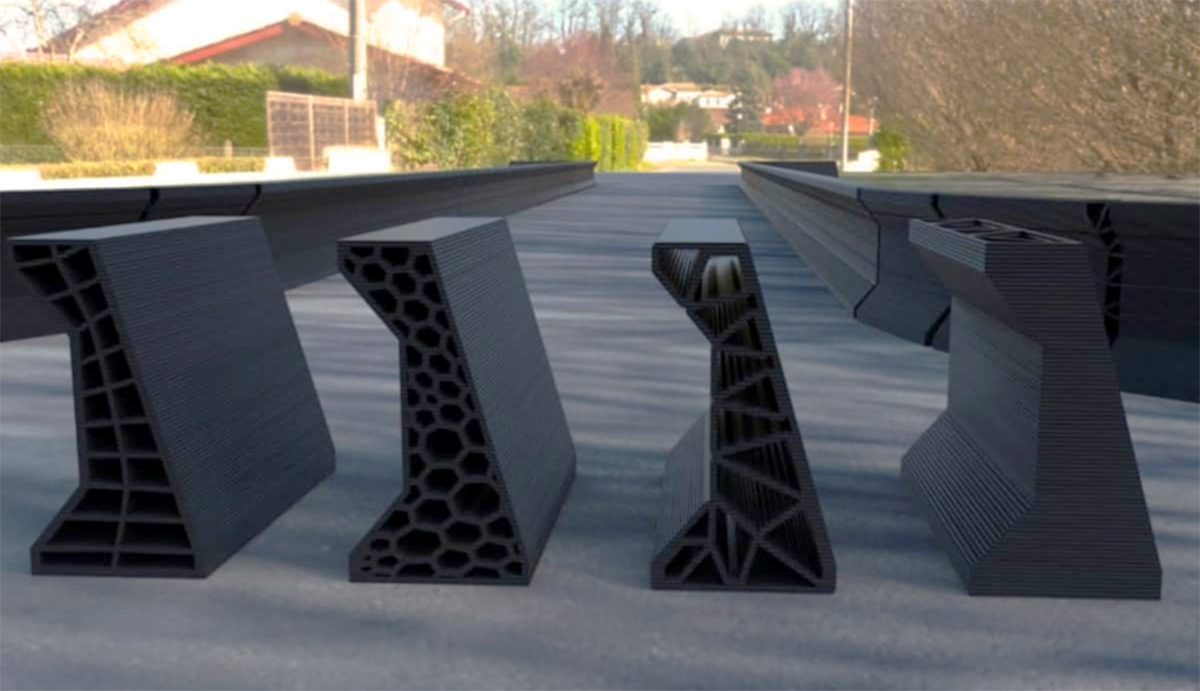

Additive manufactoring prototypes. Image © Autodesk

From aerospace engineering to sustainable architecture. An experience that shows a common thread in a research aimed at investigating the vocation of shapes, numbers and materials "both under the macroscopic and microscopic aspects". A vision according to which "by coupling geometry with numbers it is possible to shape the life of materials". Using his words this means that: "if you take the single carbon atom from Mendeleev 's table and compose it in a tetrahedron you get a diamond, if you compose it in a hexagon you get graphite, and the composition could thus go on indefinitely". But how can such a theoretical concept be translated into a concrete system that concerns real life? The Emilian engineer thinks that in a near future, Smart Cities will be able to develop precisely through the exploitation of a digital twin between the macro and micro levels of both shapes and numbers, “where macro shapes will satisfy the needs of users, spaces and the environment, and micro shapes will instead return material answers to users themselves”.. He therefore imagines that architecture and its facades can come to life as "cube sats". Thus he claims that with this widespread intelligent structure all mobile phones could be charged automatically, as well as all electric cars, which could truly become a concrete alternative to traditional mobility. And all this according to him is really possible only through a new interpretation of additive manufacturing: with that “3D printing process of buildings that is really innovative only if it allows materials speak through the integration of the physics and chemistry of the various components. As it happens in nature. As it happens in the retina of the human eye, which has a shape that follows a geodesic mapping according to the "line of minimum energy” but that actually "synthesizes the harmony of the different needs and responses of the human body itself. A natural integration that can determine the life of things, which can also trigger a rational and emotional engagement of people.”

In point of fact, throughout history it has always happened that architecture has evolved thanks to technological innovation. There have been epochal changes that have affected the language of humanistic and scientific communication only with the introduction of new instruments of dialogue between man and the nature of things or with the world itself. Today 3d printing represents a technology with unexpressed potential, which could respond to the needs or emergencies of our planet, which could certainly determine a different expressiveness and a new creative freedom in architecture as well as in other disciplines. It could perhaps contributing in lead to a new era.

Max Moruzzi at work on his 3d printer. Image © Autodesk

Read the full transcript of our interview with Max Moruzzi below:

Antonello Magliozzi: Max Moruzzi, you are an Italian engineer with a master's degree in aerospace and a twenty-year career in the design of advanced software applications for the automation of production processes. There is a common thread in your professional career: the search for innovation in materials. Where does your culture come from, can you tell us how your sensitivity towards innovation and sustainability has grown over time?

Max Moruzzi: It all started in the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines. This is where I grew up and where I started to get passionate about numbers and geometries, even though in my family they were all dedicated to agri-food sector. At university I completed my aerospace engineering studies at the Politecnico of Milano traveling every day from Piacenza to Lambrate. I then met some interesting realities and, once again, I faced the theme of geometry and numbers, and so I understood how this could express a language otherwise difficult to communicate. An ante litteram digital twin. Thanks to aerospace engineering, I began to imagine bringing this language to other sectors. Despite this, I started a fairly standard growth path for those years, I taught mathematics and I did consultancy on technologies and robotics in the food & beverage sector in Emilia Romagna. But at a certain point my wife answered for me to a job advertisement for an aerospace engineer position in the United States, without my knowledge. A position for a research aimed at developing new concepts of robotics applied to aerospace. So I received a phone call without knowing why: a job offer that I accepted, which significantly influenced my subsequent growth path towards innovation. So I moved with my family to the States and started working on the Dreamliners 787 project. That project that would later change the entire aerospace industry. A new concept of aircraft, where the shape identified by Boing had to be created with robotics and artificial intelligence through sustainable materials, such as innovative materials that had to last over time. we thus passed from the typical aluminum, an isotropic material that had dominated in aerospace, to a plastic. We have built a "plastic plane". In that period there was nothing, there were no concepts, there was no mathematics, there was only a shape, an idea and some validation. But there was no system to make it happen This was the challenge: to innovate a sector in terms of forms, productivity, automation, costs, performances and everything. From there began most of my career which then developed towards advanced materials, advanced mathematics, and digital twin with physical coupling of the processes of representation to those of production. The beauty was how this project really changed the aerospace industry. Today there is no longer an aerospace company that does not have polymers, plastics and automation robots within its processes. But the interesting thing is that all these processes, this new way of working, has "contaminated" other sectors as well. Today these processes are entering the automotive world, but also in the world of architecture and construction. The use of polymers, recycled plastics, was born from the experience gained with the Dreamliner project, the one that showed a different opportunity.

The first public appearance of the Dreamliner 787 on July 8, 2007. Image © I, Yasobara

Antonello Magliozzi: It is a really nice journey that narrate the roots of a transformation that revolutionized an industry! An evolution that you experienced firsthand and which then led you to be among the first to use 3D printing processes. May you tell us what 3d printing is for you?

Max Moruzzi: 3D printing is part of a much broader concept called "additive manufacturing". A process whereby I build something by adding material rather than removing it thanks to automation systems. An artificial intelligence that is mounted on transformation processes to govern the forms and the creative use of innovative materials. Overall, additive manufacturing allows you to build more or less as it has always been done manually, even if this process does not replicate, and cannot do it, the traditional work phases. When additive manufacturing was done with the help of robotics thinking only of replicating people's work in different phases, as happened at some point in the automotive industry, it was not possible to achieve a true innovation. The inefficiencies that previously existed have indeed remained unchanged. To be truly innovative, additive manufacturing must instead envisage a new mental process of aggregation of work in its phases, with an intelligent management of numbers and geometries according to the physical-mechanical properties of the materials.

Yes, I have been involved in 3D printing a lot in the last few years. The Dreamliners project started just like a 3d printing process. Plastic, an anisotropic material that has characteristics that depend on the shape, was spread layer by layer in order to enhance its different characteristics, in order to find the most useful configuration for aerospace components. This made me understand immediately how important was in 3d printing to combine multiple concepts, it helped me also to understand how was important a specific design thinking to determine a true freedom of forms together with the sustainability of solutions. In fact, 3d printing goes beyond building something layer by layer!

Max Moruzzi collaborate on a proof-of-concept project to 3D-print a habitat for astronauts' long-term stay on the moon, via Youtube © Autodesk

Antonello Magliozzi: How do you see the application of these scientific concepts to the world of architecture and construction possible?

Max Moruzzi: Nowadays we live in a period that represents an epochal turning point. In the field of 3d printing as well as in those of architecture and construction, there is more knowledge that tends to merge to achieve the targets of sustainability, freedom of forms and customization. Today we talk about how to customize houses, residences for instance. I'm not talking about the Freedom Tower in Manhattan, which is part of more complex speeches, with different costs and a different mission. I'm talking about simple residences that can be built at low cost with 3D printing systems, with attention to those materials that can pollute the planet less. An architecture for which it is possible to 3D printing not only the basic polymers, but also recycled plastic: I don't just print the polymers, but I also combine them with bamboo, for example. In architecture I can truly express the full potential of 3d printing! You are an architect, if you had some of the machines I'm working on available, I'm sure you could express all your creativity, without feeling the limits dictated by unsustainable costs. Those limits that derive from a traditional approach. 3d printing eliminates many barriers that limit the construction industry and architectural design today.

Antonello Magliozzi: Your vision of architecture is really interesting: a thought on the architecture of the future that tells of new forms of exploration and research. A point of view even more appealing because you are not an architect by profession and therefore you can see the matter from new perspectives. How did you approach the world of architecture, why are you so much interested in it?

Max Moruzzi: In the end, architecture and buildings are part of our life. These are things that live with us. Maybe I often take the plane, but I don't live there constantly. Instead I could say that many spaces belong to me: the room where I have the meeting, where I illustrate my projects, where I innovate, or the spaces where I find myself with my family, where I can find peace and relax. These environments are ultimately my dress. This is why I believe architecture belongs to me from a certain point of view. And then I also think about how it could be, how it could change architecture. I think that today many buildings are often already old by the time they are finished. Instead, I think that with 3d printing it could be possible to inject materials and life into architecture to make them alive. In this way we could indeed make the materials and the buildings themselves speak because they have surely something to say. We could thus listen to architecture without setting limits. That's why it interests me.

Disruptive technologies for a generative design. Image © Autodesk

Antonello Magliozzi: The world of 3d printing applied to construction is relatively young and certainly there are many topics that still need to be deepened and explored. What is your opinion on this argument? Is there a technological or cultural gap on this subject?

Max Moruzzi: Indeed, there is a considerable cultural gap, especially as regards the approach to work and knowledge of this specific topic. 3d printing requires cross functional and crossing working between disciplines that is often not there. In fact, we tend to work in a very sectorial way, while additive manufacturing requires the combination and effort of several sciences. I was among the first to think that 3D printing could be used to produce not only small objects, but also constructions on the scale of buildings. However, I must say that while I worked to "extrude projects", while I taught several start-ups to work with 3d printing, I also evaluated the existence of a big barrier to the development of these technologies: the lack of widespread education. A barrier that depend on a conservatism of politics and markets, where institutions remain passive with respect to the introduction of specific standards for the certification of materials, where many manufacturing companies, rather than favor new developments, remain focused on already consolidated processes. While many innovators and designers today are heading towards the new technology of 3d printing, this matter is in fact not yet significantly supported by specific regulations and not even by investments of manufactory companies or classic engineering houses that are often frightened just by this lack of legislation. Even in the universities of the United States, there are very few realities in which it is possible to experiment with these technologies on works of large volumes or dimensions. And, precisely in the United States, this lack of specific studies and legislation can only be bypassed with “walk around” strategies. To proceed with the construction of buildings with 3d manufacturing processes, these in fact require very expensive insurance policies, with investments that are sometimes higher than those of the buildings themselves. This is due solely to a lack of legislation and knowledge of the sector. Therefore, in this sense, today also costs can constitute an important barrier for the sustainable development of this technology. There is therefore a real gap in the knowledge, experimentation and certification of 3d printing products. A gap that in my opinion can only be filled with educational action and, thanks to artificial intelligence tools, also through "self-training" tools.

Additive manufactoring prototypes. Image © Autodesk

Antonello Magliozzi: I know that you are carrying out an important 3d printing project concerning construction in Italy. Could you describe us what it consists of and what innovations it contains?

Max Moruzzi: It is a beautiful project born from the collaboration with an Italian company located in Venice province, that is called Breton SpA. A company that has historically always made machine tools, that now feels the need to enter the world of 3d printing in a different way. The project leverages the promoter's strong background in building materials knowledge and involves the construction of an innovative 3D printing machine, with the aim of revolutionizing the construction market. A new 3d printer that will be ready for the Christmas time and that will have the distinction of being the largest ever made in Europe. Beyond its size, this machine is different from others already made in the way it is conceived, because it includes artificial intelligence systems that allow the production of shapes and combinations of materials, otherwise difficult to make. A machine that will allow us to build scientific prototypes and demonstrations with the intent to educate and remove the biggest obstacle to the development of 3D printing technology. A tool to eliminate all the “antibodies” that there are today in the construction market, those called lack of certification and conservatism, to eliminate the preconception that 3D printing can limit creativity. An educational, a qualifying and engagement tool: It will become a magic pen that will help architects like you to customize their projects.

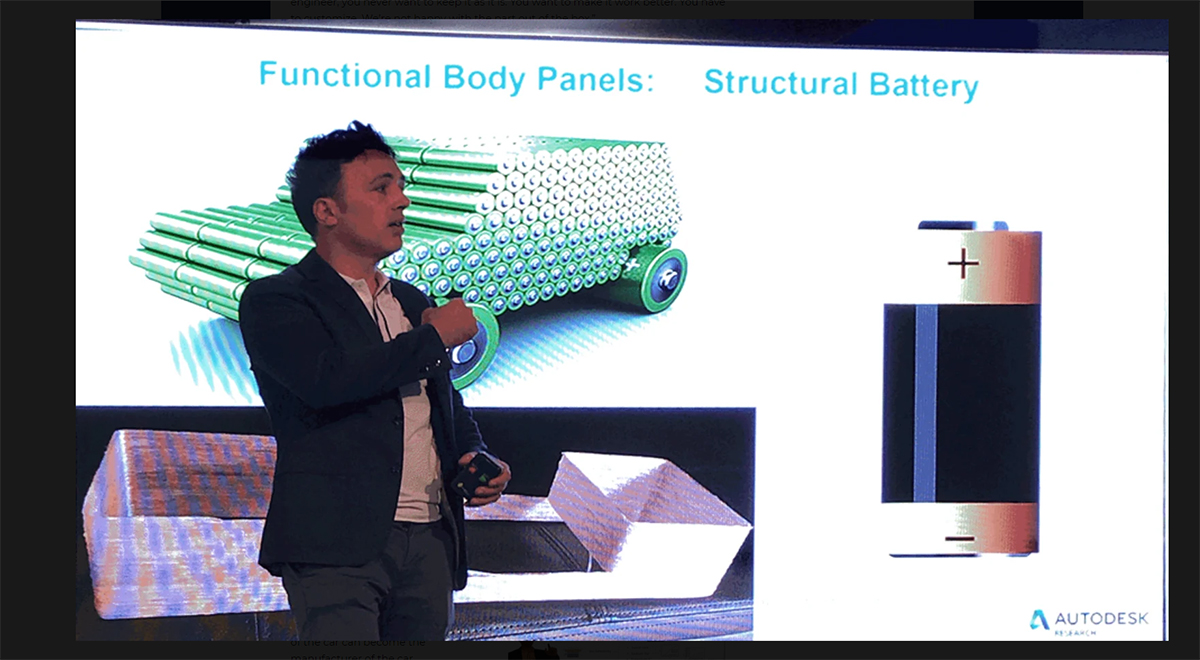

Max Moruzzi explaing how a building could be a battery. Image © Autodesk

Antonello Magliozzi: And what prototypes are you planning to make?

Max Moruzzi: The prototype I'm working on concerns an intelligent facade and therefore regards an important part of the construction. What do I mean by a smart facade? I mean first of all a facade that has no limits of shape and, of materials - for example, it can include the use of recycled plastics - and that can to be "alive". I mean: a prototype designed to add and integrate different materials, including conductive ones, in order to make the facade itself work like a battery. A living façade "also means that the characterization of its shapes can count on the use of specific materials that actively contribute to cleaning the air, thus making the building itself as a large lung. Instead of producing CO2, the prototype of the facade can produce oxygen, I am not saying that it can reduce entropy because this cannot be done, but it certainly can help in preserving the planet.

Antonello Magliozzi: From aerospace engineering to sustainable architecture. Your experience always shows eclectic interests and knowledge that focus on the vocation of materials. Can you explain how you work in shaping materials? And how do you think innovative materials such as those of your 3D printing prototypes can change the face of cities in the future?

Max Moruzzi: I studied shapes both in the macroscopic and microscopic aspect. Indeed, lately it is precisely the micro and nano aspect of the geometry of the shapes that interests me a lot. in the end, by coupling geometry to numbers it is possible to give a shape to materials' life. In fact, if you take the single carbon atom from Mendeleev’s table and compose it in a tetrahedron you get a diamond, if you compose it in a hexagon you get graphite, and the composition can thus go on indefinitely. In architecture, by combining geometry and numbers we can discover a world that we have just begun to see. We can discover the true vocation of the materials. The face of cities can in fact change through the combination of macro and micro shapes. Thus, in architecture, the digital twin between the two levels of shapes and numbers will become a priority, where macro shapes will satisfy the needs of users, spaces and the environment, and micro shapes will instead return material answers to users themselves. Architecture and its facades will be able to become alive as a "cube sat". Today many major companies launch these cube sat to spread communication across the planet and spend billions of dollars. With a billion dollars I could completely change Milan, turn it into a large cube sat through the intelligent facades of its buildings. In this way, all mobile phones could be charged automatically, as well as electric cars, which could truly become a concrete alternative to traditional mobility, unlike what has happened so far. Similarly, autonomous driving could also become real thanks to a widespread intelligent structure. All this may happen thanks to a new concept of “additive manufacturing” processes: the 3D printing process of buildings that is really innovative only if it allows materials speak through the integration of the physics and chemistry of the various construction components. As it happens in nature. To use a metaphor: as it happens in the retina of the human eye, which has a shape that follows a geodesic mapping representing the "line of minimum energy", but which also represents much more: synthesizes the harmony of the different needs and responses of the human body itself. A natural integration that can determine the life of things, which can also trigger a rational and emotional engagement of people.

Top image courtesy of Forma Mentis.