Submitted by Mert Kansu

Can experiences of US cities be an inspiration to Istanbul’s impending water & construction crisis?

United States Architecture News - May 13, 2019 - 18:57 11109 views

"You don’t want to walk and talk about Jesus; you just want to see his face," has concluded the environmentalist and architect David Waggonner’s interview with The Atlantic[i]. This quote has been more than a Rolling Stones lyric in recent years. It has become the mentality of environmentalists and designers in how they interact with water in cities. Research shows that people living in urban areas now make up more than half of the world population[ii]. Although cities dominate the way we live and work, the word water is talked, discussed a lot, but never made visible, especially in those with climatic vulnerabilities. Instead, water is shunned and pushed away outside of, or under cities. Often only made apparent in urban fringes where no one can hear or see the water. A movement that has been made popular recently, learning through place and experience has been theorized and applied by many educators, philosophers, writers, and thinkers long ago. Jean Jacques Rousseau materialized his vision for education in 1762 with his book, Emile[iii]. He believed that analytical thinking and studying are not the only crucial instruments in educating the young.

For him, as much as a child don’t lose her instinctual sensations and reactions that she was born with, she will be closer to being a better person. Russian writer and philosopher Leo Tolstoy also interpreted and applied this and many other theories in his school in Yasnaya Polyana, dated 1859[iv]. He believed the essence of teaching lied in giving the young the value of respecting others and vast freedom. He and the likeminded educators of his day believed in educating students in gardens, forests and other natural places that define the place they live. Tolstoy wrote, giving children the freedom to experiment, explore and experience were the keys for them to become an adult who is aware of her surroundings. Today, it is clear that many nations have neglected this educational theory. A megalopolis like Istanbul is at a breaking point where it rapidly has to make a decision on how it interacts with nature or face even worse consequences than it already is experiencing. Amidst natural disasters, floods, water shortages, significant and prestigious construction projects are more attractive to investors and state officials.

Aerial view of the airport construction. The airport sits on the biggest fresh water basins of Istanbul. Image © RASAT

3,500 flights and 411,000 passengers per day, six runways, and 1.6 million square feet of area cover[v]. Recently opened Istanbul airport claims to be bigger than the Manhattan island and the biggest airport in Europe. Sited in one of the most important wetlands in the Istanbul metropolitan area[vi], it sits on one of the biggest freshwater basins of the city serving more than 16 million citizens of the megacity. The project passed through one of the most controversial approval processes among many other construction projects in Istanbul. Some, without a doubt, love it and hated by many[vii]. Although surrounded by water on all sides and having a mild Mediterranean climate, Istanbul has a recent history of struggling to serve its citizens' fresh water[viii]. However, such megaprojects being sited on ecologically sensitive areas, climate change, droughts and increasing floods do not seem to be caused by a lack of natural resources or disadvantages of geography. In contrast, the lack of knowledge in planning, design and awareness of water and nature seems to be the reason on many occasions.

A profession like architecture that enables these large projects can also be the remedy to these wicked problems. Architecture can bring creative solutions designs and manage multiple parties. It is a profession which response to peoples’ needs but also touches peoples senses, helps bring communities together and draw light into global problems. Therefore, this essay examines the role of architecture, design and education to raise water awareness, to create more integrated communities that not only are aware of how water works in their city but also demands to live in places that respects and acknowledges the needs of water flowing on, under and in their town.

A city that has become illiterate on the water shortly after its early years but recently has been on the road of making a comeback on educating its citizens in New Orleans. For some, the city is a beautiful and eclectic mix of cultures, French colonial architecture with Creole creativity and tang. However, for most residents, it is a bowl that fills up with every inch of rain. It is inequality, insurance debts, and poverty. Geologically made up of the permeable ground cover and geographically shaped like a tub[ix], New Orleans is an engineer’s nightmare. For years, the city has raged a war against the water by boarding up every foot of the Mississippi River. While the river tried to build up alluvial soil on the banks of the crescent city which made up most of its natural high ground, people continued to sink the city by blocking the river with concrete levees and floodwalls[x]. In New Orleans, the hardest hit areas are mainly occupied by African Americans. In addition to these neighborhoods being vulnerable areas, they are also areas where income and education rates are the lowest in the Orleans Parish[xi]. Most of the residents of Eastern New Orleans, Lower and Upper Ninth Ward while living couple feet across the water, have been witnesses to old, cracked concrete walls trying to hold off the water in a city encroached in the bends of the largest drainage basin in the United States[xii]. On August 2005 Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana, left 1,833 deaths, $108 billion [xiii] of total financial loss and a seemingly never-ending and one of the most sophisticated recovery planning processes in the United States[xiv]. While insults and arguments flew back and forth between planners and policymakers like a fiery ping-pong game, some people have chosen to take a different path to invite water back to New Orleans.

Aerial image of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, courtesy of Pixabay.com

Elevation map of New Orleans, blue colors indicate elevations below sea level. Image © USGS.

Ripple Effect is a K-12 education nonprofit that began in a classroom in post-Katrina New Orleans. This organization envisions a future where all students and families have the knowledge and creativity they need to strengthen communities in an era of climate change and sea-level rise and defines water literacy as the systematic collection and sharing of knowledge that all citizens and communities need to successfully adapt to changing environments; investigated primarily through human relationships to water and water systems [xv]. Since 2013 Ripple Effect has worked with teachers, scientists, and communities to develop, test, and teach water literacy curriculum in high-need schools.

There are also more architectural responses that take a water-centric approach to revitalize New Orleans. David Waggonner, an urban and environmental architect, has started a series of conferences called Dutch Dialogues. “The three New Orleans conferences brought together landscape architects, hydrologists, urban planners, economists, politicians, community leaders, and hydraulic and civil engineers. The first conference, in 2008, was information exchange, the second, in 2008, focused on designing and “reformatting the city” as Waggonner describes it, and the third, in 2010, added more details to the design. The workshops were co-sponsored by Louisiana organizations, Dutch organizations and the American Planning Association.” [xvi] His firm Wagonner&Ball is also responsible for designing an award-winning proposal named Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. “The Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan is a water-based landscape and urban design proposal that illustrates how the region can live with water rather than fight against it. Building on the knowledge and partnerships developed during the firm’s Dutch Dialogues symposia, Waggonner & Ball led a team of over twenty firms and expert advisors to develop the multi-scaled, actionable strategy.” [xvii] “The Water Plan integrates infrastructure planning and urban design across three hydrological basins. It employs a multi-layered, ground-up approach that is science-based, place-based, and adaptable. The plan proposes a new investment model for public works, wherein spending on streets, canals, pump stations, and stormwater detention basins enhances the public spaces that are so vital to life in the region and yields opportunities for economic growth and development. Proposed retrofits strengthen the function of existing water systems, make use of undervalued water assets, and enhance key corridors.” [xviii]

Another hotspot for climatic disasters, floods and water management issues is in the West Indies. Miles away from Louisiana into the Atlantic is Puerto Rico, “a territory belonging to and bound to the laws of the United States that are outside of United States national border”[xix]. Being ruled under the US government, the post WW2 transformation took its toll on Puerto Rico with “Operation Bootstrap.” The island was transformed as any other city in the mainland. Railroad lines were abandoned. Instead, highways have been built and wetlands have been filled to accommodate construction of more factories, energy plants and ports[xx]. In an island that has a tropical climate, remote location and no fossil fuel sources, this type of development has shown its short-comings at every climatic disaster. Currently, only 2% of Puerto Rico’s energy portfolio is from sustainable energy resources leaving it to be bound to fossil fuel[xxi]. Besides, due to the Jones Act[xxii], the freights which has to arrive from the mainland has to pay a higher tariff[xxiii]. The island is equipped with old and unmaintained energy infrastructure[xxiv]. Hurricane Maria in 2017 left electricity infrastructure unusable and destroyed islands’ ports. After the event, Puerto Rico was unable to receive electricity for 11 months[xxv]. The loss of the already financially stressed territory was 43 billion dollars [xxvi] with added life loss of 3,000[xxvii]. Many patients in hospitals waited for the gas to power their generators, and the majority of the population was without regular access to fresh water[xxviii]. With significant ecological resources but wrong planning practices, climatic vulnerabilities and a lack of fossil resources, it becomes a must for Puerto Ricans to learn how to live with the land, natural resources they have and respect the flow of the water.

Hurricane Maria over Puerto Rico. Image © NASA

Para la Naturaleza, an environmental NGO dedicated to connect and educate people for a Puerto Rican environment where children “can grow up inhabitable cities, swim in the crystal-clear waters of our (Puerto Rico’s) rivers and feed themselves off the land.”[xxix]. Para la Naturaleza advocates putting 33% of Puerto Rico under conservation. With the US and Costa Rica having 26% conserved land, Dominican Republic has 24% percent and US Virgin Islands having nearly 52% of its land under conservation Puerto Rico’s current 16%[xxx] of total land conservation becomes a major indication of the reason for the severe consequences that citizens face. Para la Naturaleza also organizes activities with communities living around the island to increase awareness for land and water conservation as well as training people in sustainable energy production methods.

Children during an activity in the annual fair organized by Para la Naturaleza. Image courtesy of Para la Naturaleza

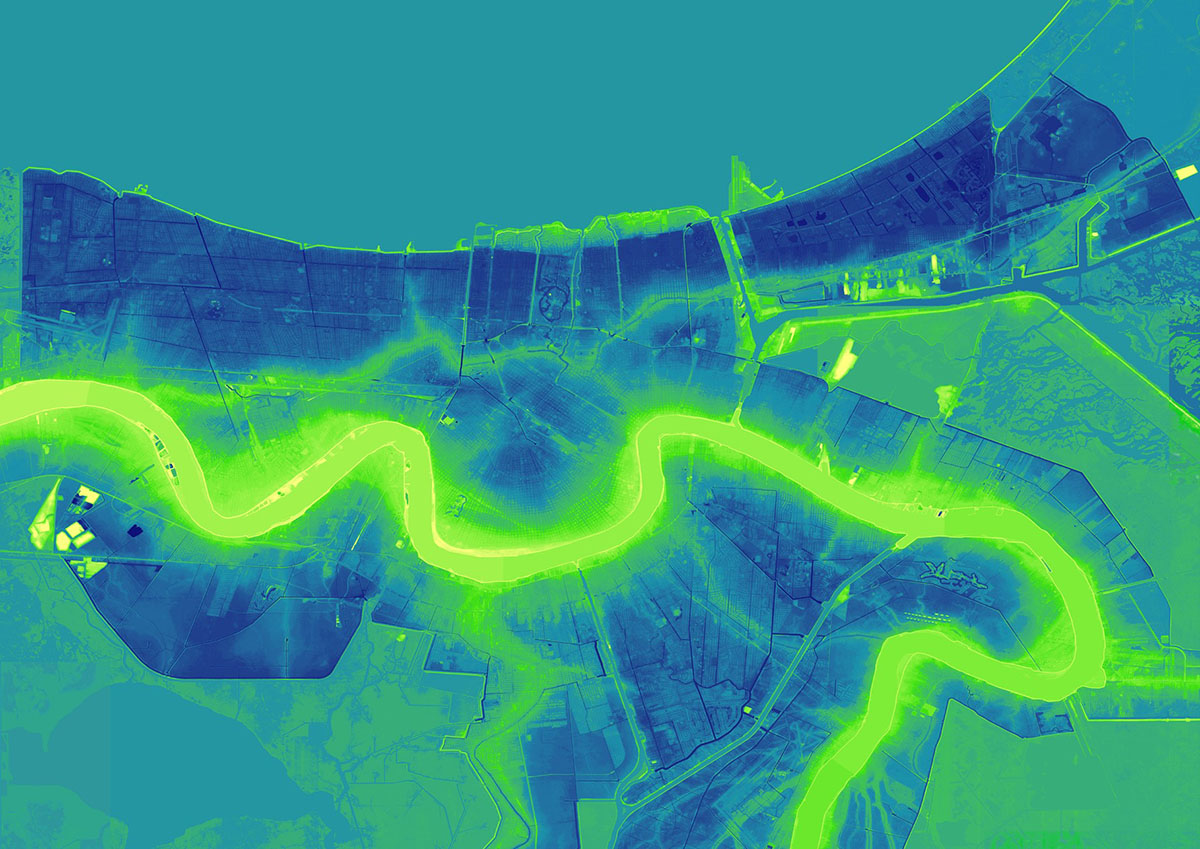

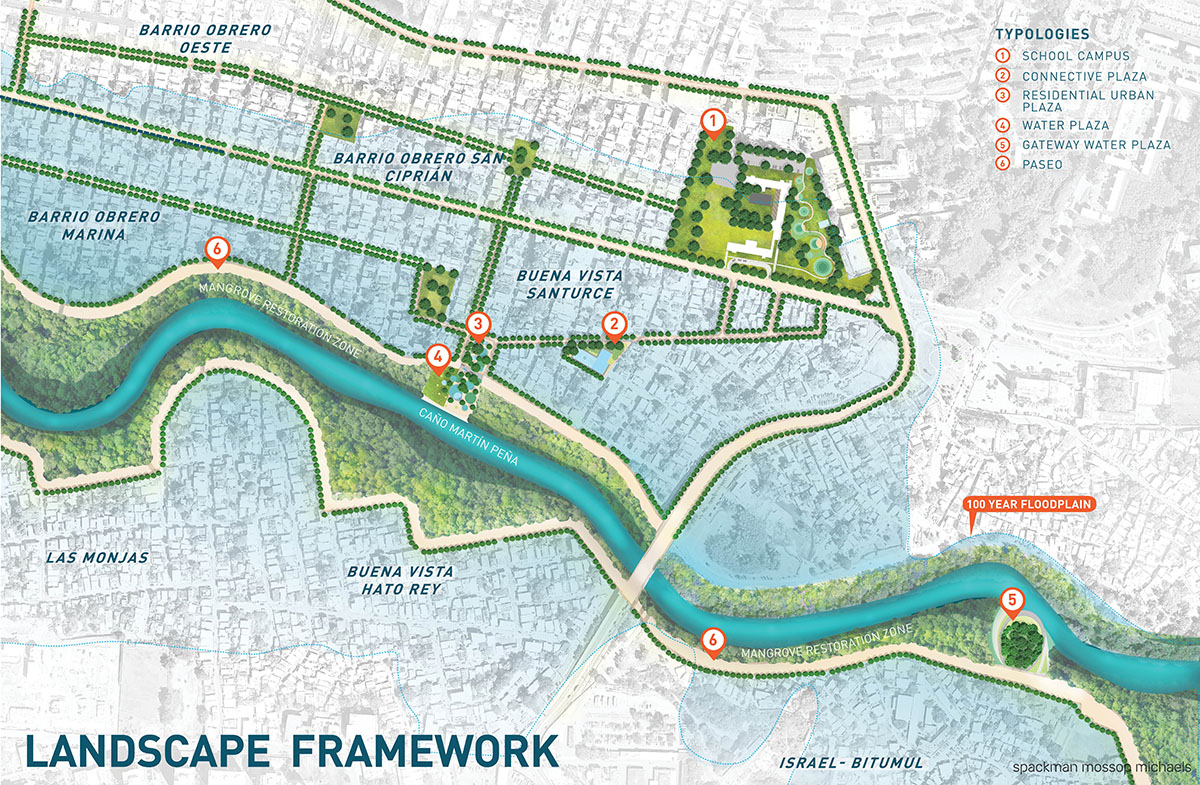

An architectural proposal in the biggest city of Puerto Rico, San Juan, has been made for the Martin Pena canal and the neighborhoods that are living along with it. The proposal made by Spackman Mossop Michaels which is a landscape architecture and an urban design firm based in New Orleans has won the Caño Martin Peña Restoration Project funded by the EPA Smart Growth Implementation Assistance Program[xxxi]. It imagines a new waterfront to an unplanned, vulnerable, and an urban area along the canal. The Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) summarizes their design intent as “The final report proposes a series of interconnected water plazas and green infrastructure to clean the water and reduce flooding, while also creating a framework of civic open spaces to strengthen the social fabric of the community.”

Image © Spackman Mossop Michaels

Image © Spackman Mossop Michaels

Image © Spackman Mossop Michaels

If there is one thing that Istanbul can take from these case studies, it would be that the city should not wait for a catastrophic disaster to happen before trying to implement solutions and decrease the effects of climatic hazards. Both technical data, media articles, and news stories show that there are increasing problems in flood and water management as well as citizens’ knowledge and awareness in climatic issues[xxxii]. These infrastructural mega-projects like this new Istanbul Airport and the 3rd Bosporus bridge are not only is controversial because of their size and location where the already decreasing forests and water resources are being put under danger but also being a gateway to new developments that may start emerging near these projects. Istanbul is a 3000-year-old city with a historic culture and knowledge about water.

Istanbulites have been more accepting and aware of the water that surrounds their lives. During Byzantine and Ottoman periods water has been carried from the mountains with miles long aqueducts. Other infrastructures like the Basilica Cistern helped store water, and water gages helped moving water around the city. During the Ottoman Empire period, one of the most essential services to the people the Sultan made was to build fountains. These structures became a place where people came to get water, meet, talk. To these types of social catalyzers, other daily activities accompanied. In Istanbul, the same water source was used by Muslims who performed ablution with water before their daily prayers, by Christians who baptized their children, and by Jewish who also purified their body as a ritual. Today, this everyday activity seems to have been forgotten by people who still drink from fountains, people who buy generic bottled water, or some who order imported European water as the first thing they do at a restaurant.

Basilica Cistern at Istanbul, courtesy of Pixabay.com

Their steps were taken towards water literacy, however, they seem to get shadowed in media by the hubbub of daily political discussions. Some private and state organizations are already working to increase awareness of water and nature. Private organizations like Tema and Cevre Foundation hosts conferences and creates reports on water usage and knowledge in Istanbul. Istanbul’s municipal water agency ISKI has an educational program that travels schools around the city to create awareness to children on how they use water. A water museum sits in the outskirts of Istanbul, Terkos. After completing its construction in 2011 and winning the National Architectural Award, the restored water pump station and museum still sits abandoned due to permitting problems between different levels of bureaucracy.

The examined case studies show that water management and climatic disasters are complex issues that can be only tackled with a multidisciplinary approach and support of the community. There is a need for a top-down as well as a bottom-up effort that needs to play within the urban context. What designers or architects can do in this case has two prongs to it. One, in the educational field, designers can use their skills to develop and present the issues of climate change, floods, and water management to the general public and the youth by distilling the complicated matters to its fundamental principles. If adequately integrated within the educational system, children can start to gain awareness in these issues with design exercises, real-life models, simulations and field trips within their city. Second and finally, on a more architectural and planning front, designers should be aware of their local sensibilities on climate and ecology. Designing with an awareness that each city has a unique climatic or ecological condition, and with the purpose of creating spaces that foster social interaction where citizens can form stronger communities. These efforts will result in citizens that take pride and responsibility in the places they live in and work together to solve problems.

Aerial View of Istanbul, courtesy of Pixabay.com

References and Further Readings:

[i] O'Neil, Lorena. Why Doesn't New Orleans Look More Like Amsterdam? 2 September 2015. Article. 6 May 2019.

[ii] Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser. Our World in Data. 15 September 2018. 5 May 2019.

[iii] Rousseau, Jean Jaques. Emile, or on Education. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1921. Book.

[iv] Ormell, Chris. Tolstoy and Education what can we learn from Tolstoy’s school at Yasnaya Polyana? Transcript. London: Prospero, 2011. Document.

[v] Kucuk, Mustafa. 150 milyon yolcu kapasitesiyle dünyanın en büyük havalimanı olacak. Istanbul: Hurriyet, 8 June 2014. Newspaper Article.

[vi] Kaya, Axelle and Menekse Kizildere. Istanbul’daki Icme ve Kullanma Suyu Havzalarinda Arazi Kullanimi. Report. Istanbul: TMMOB, 2013. Document.

[vii] Fistik, Firat. "Controversies surround Istanbul’s new airport." 24 November 2018. Journo. Article. 5 May 2019.

[viii] Ritter, Kayla. "Drought, Pollution, and Expansion Imperil Istanbul’s Best-Laid Water Plans ." 19 April 2018. Circle of Blue . Article. 7 May 2019.

[ix] USDA. Soil Survey of Orleans Parish, Louisiana. Report. New Orleans: USDA, 1989. Document.

[x] Campanella, Richard. Three Hundred Years of Human Geography in New Orleans. Report. New Orleans: Data Center, 2018. Document.

[xi] Katz, Bruce. "Concentrated Poverty in New Orleans and Other American Cities." 4 August 2006. The Brookings Institution. Article. 7 May 2019.

[xii] North Pacific LCC Data Coordinator. North American Watersheds. 10 Jan 2014. Article. 5 May 2019.

[xiii] Zimmermann, Kim Ann. "Hurricane Katrina: Facts, Damage & Aftermath." 27 August 2015. Live Science. Article. 7 May 2019.

[xiv] Johnson, Olansky and. Clear as Mud-Planning fo the Rebuilding of New Orleans. Chicago: American Planning Association, 2010.

[xv] Ripple Effect. 2019. Web Site. 30 May 2019. .

[xvi] O'Neil, Lorena. Why Doesn't New Orleans Look More Like Amsterdam? 2 September 2015. Article. 6 May 2019.

[xvii] Wagonner&Ball. Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. 1 January 2013. Web Site. 22 June 2019. .

[xviii] Wagonner&Ball. Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. 1 January 2013. Web Site. 22 June 2019. .

[xix] US Constitution. "STATES, CITIZENSHIP, NEW STATES." 21 June 1788. Constitution Center. Document. 6 May 2019.

[xx] Lehman College. "Operation Bootstrap Center for Puertorican Studies." 6 May 2018. Lehman College. Web Article. 6 May 2019. .

[xxi] EIA. "Puerto Rico - Territory Profile and Energy Estimates." 19 July 2019. EIA. Article. 10 May 2019.

[xxii] Rosa-Aquino, Paola. "What will a Jones Act waiver mean for Puerto Rico’s 100% renewable energy goal?" 26 April 2019. Grist. Web Article. 4 June 2019.

[xxiii] Carroll, Rory. "U.S. shippers push back in battle over Puerto Rico import costs." 9 July 2015. Reuters. Article. 06 May 2019.

[xxiv]Yalixa, Rivera and Levin Jonathan. "Puerto Rico Asks Buyers of Rickety Power System to Rewrite Rules." 11 June 2018. Bloomberg. Article. 6 May 2019.

[xxv] Campbell, Alexia Fernández. "Vox." 15 August 2018. It took 11 months to restore power to Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. A similar crisis could happen again. Article. 7 May 2019.

[xxvi] Associated Press. "Puerto Rico lost $43 billion after Hurricane Maria, according to govt. report." 4 December 2018. NBC News. Article. 7 May 2019.

[xxvii] Gorman, Steve. "Puerto Rico's death toll from Hurricane Maria raised to nearly 3,000." 28 August 2018. Reuters. Article. 7 May 2019.

[xxviii] Schmidt, Samantha. "Water Is Everything." 12 September 2018. The Washington Post. Article. 6 May 2018.

[xxix] Para la Naturaleza. About us. 6 May 2019. Web Site Post. 6 May 2019.

[xxx] Recovering Together - 2017 Annual Report. Annual Report. San Juan: Para la Naturaleza, 2017. Document.

[xxxi] Landscape Architecture Foundation. "Caño Martin Peña Restoration Project." 20 March 2018. Landscape Architecture Foundation. Article. 6 May 2019.

[xxxii] Kousky, Carolyn. How America Fails at Communicating Flood Risks. 11 October 2018. Article. 05 May 2019.

Top image: Satellite image of Istanbul. The new airport has been built on the north western forests of seen in the image. Image © NASA