Submitted by Tarun Bhasin

Indian Team placed 3rd in FuturArc 2019 Professional Category

India Architecture News - Aug 01, 2019 - 06:43 5607 views

BCI Asia awards concluded in Bangkok, Thailand on 18th June 2019. It recognized the top ten architects and developers of Thailand. Along with them, awardees being recognized under other awards categories such as the FuturArc Green Leadership Awards, and FuturArc Prize 2019, were also present. A month after the conclusion of the awards, the Indian team comprising of three graduates from the School of Planning and Architecture Bhopal is trying to shake-up the architecture and planning scene in the city of New Delhi, out of which their competition entry is based. Yug Aggarwal, a Delhi-based architect, who was also the team leader of the trio that comprised of Manu Dhanked (presently practicing in Germany) and Tarun Bhasin (incoming M.Sc. candidate at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit, UCL and India Reporter of World Architecture Community), was present at the event to explain the key agenda behind his project.

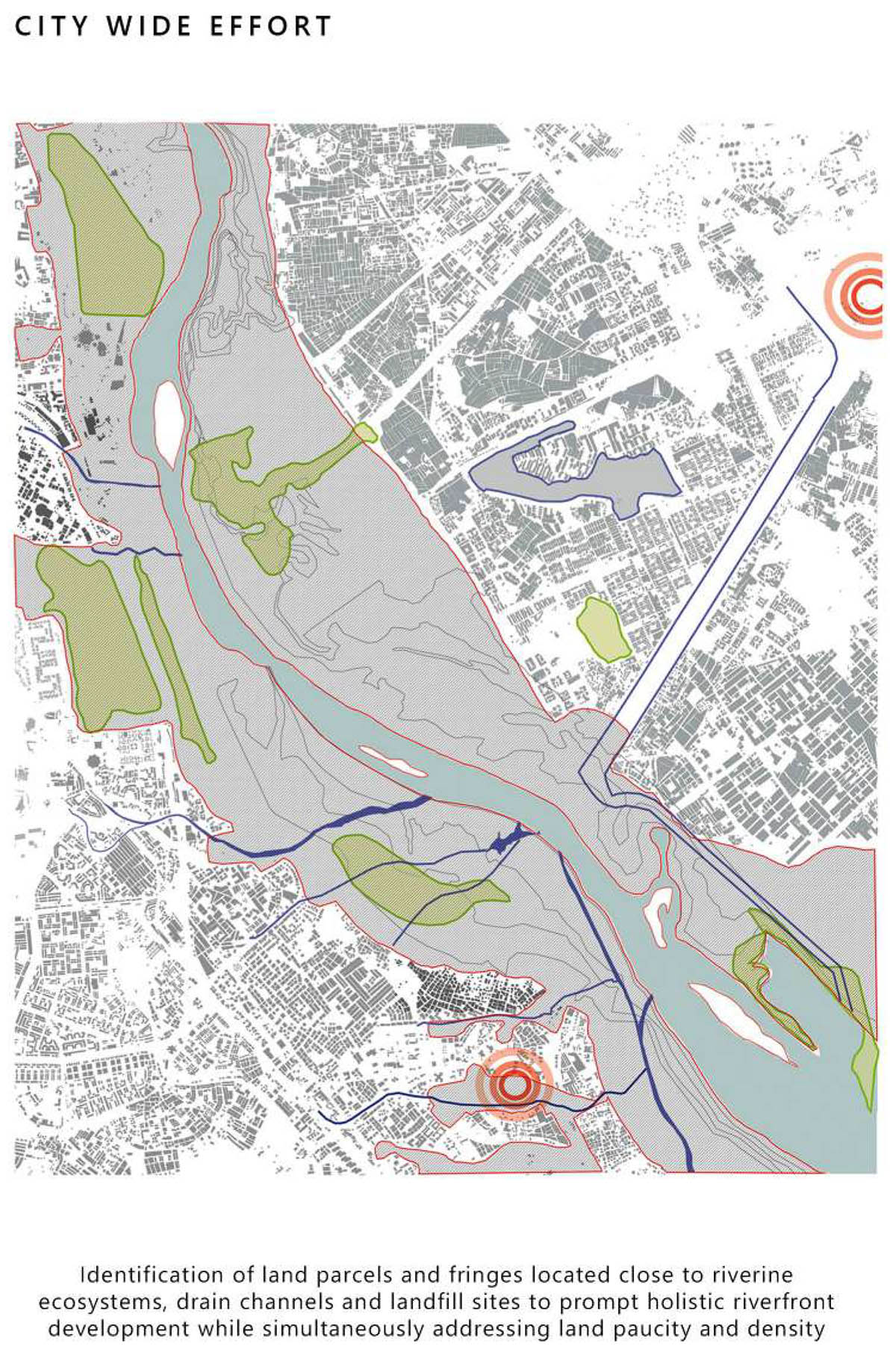

For context, the brief of the FuturArc Prize 2019, asked teams globally, to address the issues proposed by hyperdense settlements in Asia. It asked the teams to select a site of no less than 1km2 and propose a settlement that would provide dwelling and economy to no less than 100,000 people. The teams were also required to inculcate neighbourhood development, city-wide engagement efforts and sustainable design interventions in their projects. The Delhi based group, being the first out of India to be recognized with a position in the professional category, came up with the idea of tackling the masterplan of Delhi by dealing with its sewerage system to tap into vast pools of land adjacent to its edges that lie vacant and neglected.

Yug Aggarwal (left) at the event. Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

Tarun Bhasin: Can you explain how you came up with this idea as a response to the brief, and what is the driving agenda behind your proposal?

Yug Aggarwal: Right after graduating in 2017, we started engaging as architects in New Delhi. During that time, the recent proposal for the masterplan of the city was revealed. The masterplan sought to cut 15,000 mature trees from central areas of the city to make space for future housing and commercial projects. It faced huge flak from the public of Delhi, which came onto the streets to stop the felling of trees. Protests on social media led to an even larger outcry, and petitions in the court finally put a halt on the entire programme leading to a successful roll-back of the masterplan, that if otherwise implemented, would have choked the city furthermore.

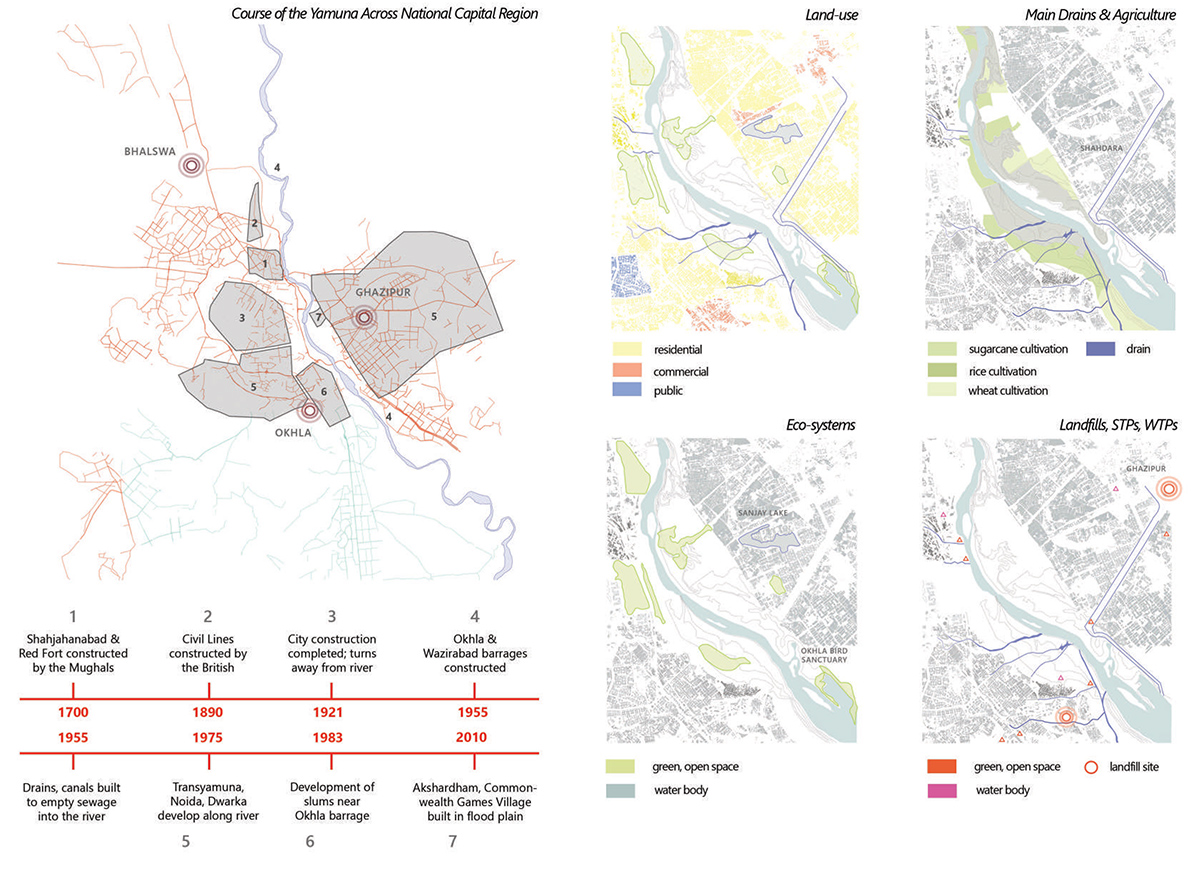

Within this, we couldn't help but wonder, that space for more development was required indeed; Delhi is a city that is characterized by low-to-medium rise structures - thus, in this scenario, how could more space be made available for the city's economy to grow and its capacity to absorb migration remain, without hampering its current fabric. That is when we started looking into the story of the city historically.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

Delhi is a very suggestive and moralizing place, where the stupendous amount of wealth has passed and is passing away. The city has slowly done away with its roots, merchandised it, encroached it, and spoiled it all. Its colonial planning mindset effectively intrudes in the social fabric of urban life, removing people and places representing the lowest level of decision making. It sees marginal economies as a hindrance to progress and seeks to replace them with technology.

We realised the sewers of Delhi are one such technology that divides the city’s socio-cultural footprint into enclaves and choke the ecological fabric that exists along river Yamuna, further aggravating the situation for farmers that borrow water from the river to irrigate their fields, bringing them more flak for adding pollutants in the food cycle of the city. The city’s disconnected places increase dependency on automobiles. Whatever technology cannot replace is thrown at the edge of the state boundary, away from the cleanliness of urban life, creating vast mountains of garbage at urban peripheries.

The result – Delhi represents the most polluted air, water and terrestrial landscape in the country. The agricultural fields, landfill sites and edges of sewers – all are associated with undesired collective memories, whose existence remains unacknowledged by the social processes of the city. As the city expands rapidly, it is engulfing these fringes that are considered externalities; blatantly refusing to adhere to critical issues that can help it tap into huge portions of underutilized land and emancipate the marginalised.

On observing this almost orchestrated composition of the city's waste cycle and its relation to the failing infrastructure, we understood that the preservation of wealth and welfare of communities and advances in culture and civilization depended on how the sewage [garbage] issue is dealt with - and for Delhi to move forward, the only way left is to deal with it now, and to recognize the people (communities) that have kept its systems functional so far.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

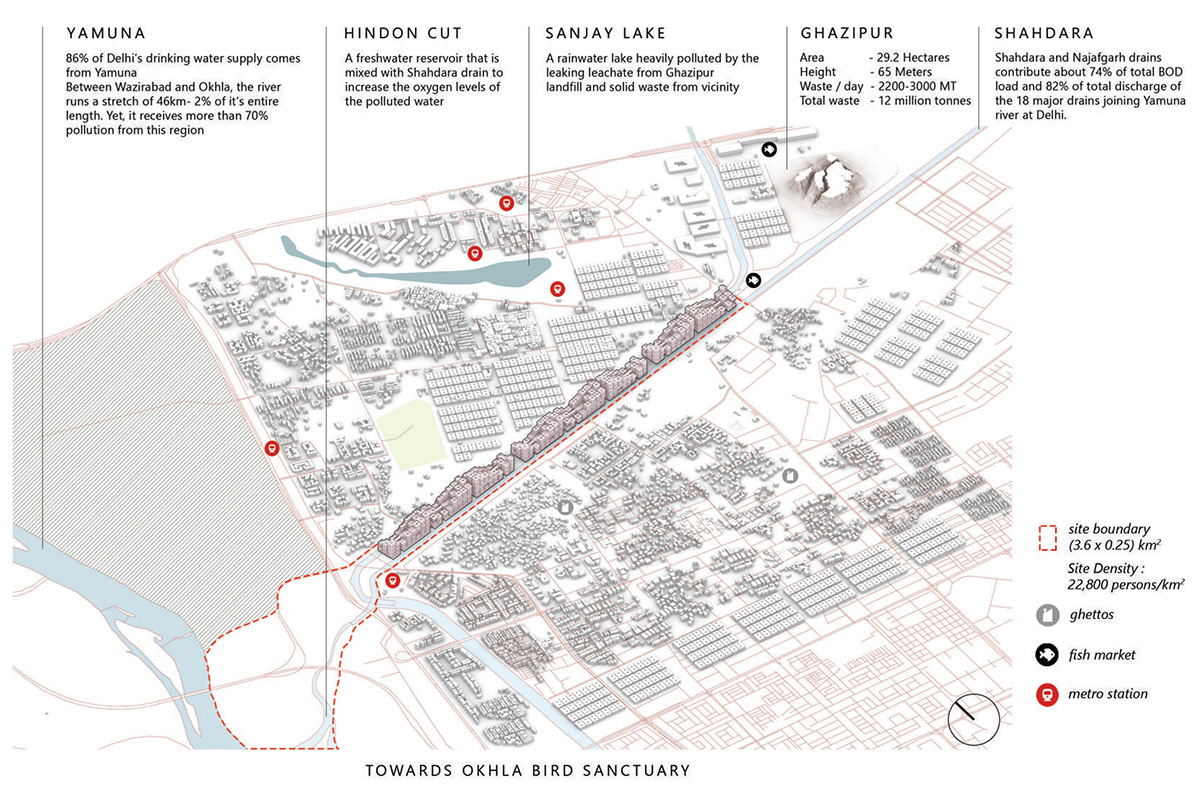

For our case the site for built programme is a 3.6Km x 250m space between the Hindon Canal and Shahdara drain (the second-largest sewer of Delhi) with either ends marked by Ghazipur landfill (the largest dump yard in Delhi with a height of 29m spread over 69 acres, adding a daily waste of 2000 tonnes), and Yamuna floodplains representing the cumulative project scheme. Both the edges of the site are marked by block frontages of lower-income neighbourhoods that remain disconnected from each other. The site provides a livelihood to marginal workers such as underaged ragpickers (all Dalits – a lower caste community), farmers, washermen, fishermen, etc. that face a lot of social and political discrimination for being associated with the economy of the site. It is dotted with freshwater sources and Okhla Bird Sanctuary in its context forming a network of ecological zones that cater to migratory and indigenous species of birds. The Shahdara drain carries refuse from entire East Delhi polluting the Hindon Canal, Yamuna, and the Okhla Bird Sanctuary.

Thus the driving agenda behind the proposal was to address the social mindset of city planning by taking marginalised societies on the site as primary stakeholders and engaging them with the landscape to help treat sewage water, cure the landfill, mainstream agriculture and fisheries, and introduce a cyclic economy of material reuse. Our design, thus, represents spaces that are created to support the socio-economic structure, devising a holistic waterfront development and an inclusive masterplan for the entire city to counter the problems that plague its growth.

Image Courtesy: FuturArc Prize 2019

Tarun Bhasin: Looking at such a fragmented context, both at policy and planning level, what was the idea behind the neighbourhood you conceived; and what values do you want to purport to the city through it?

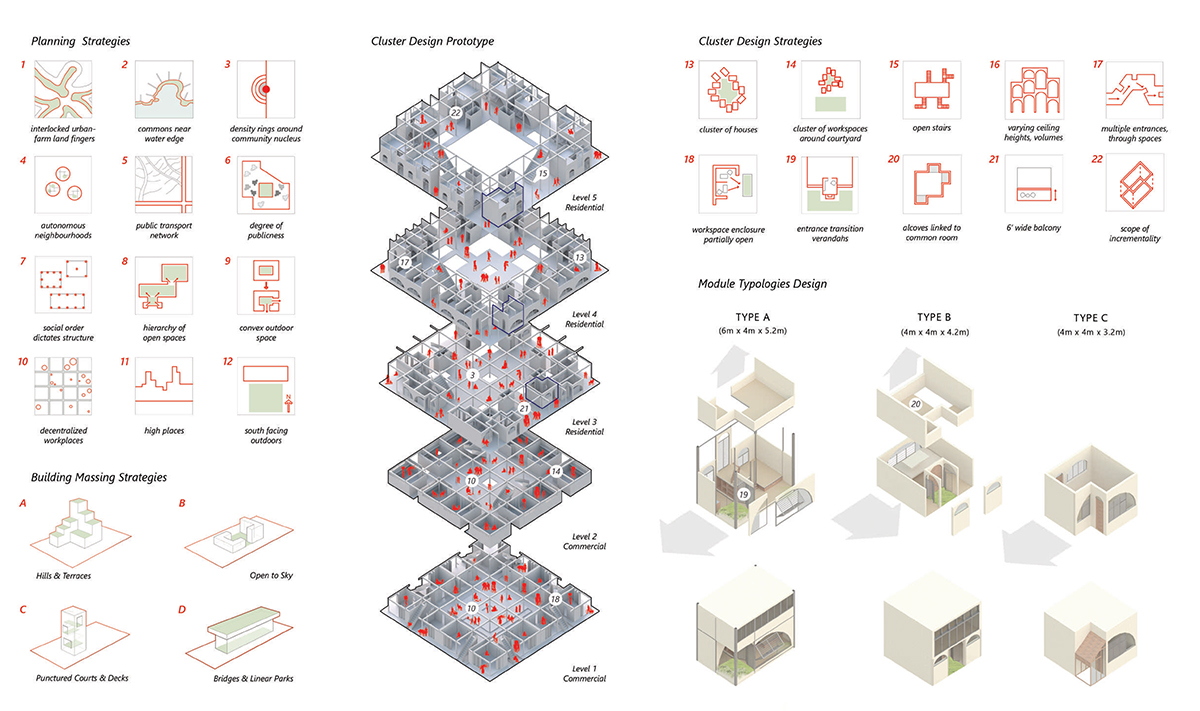

Yug Aggarwal: Delhi’s current zoned planning system divides its fabric into monocultural residential, workplace or marketplace enclaves that are spread out and disconnected. Thus, a great chunk of the population (although only 35%) utilizes automobiles for the daily commute, choking the city infrastructure and atmosphere. Providing respite, the proposal is a mixed-use co-living co-working built programme, that borrows from space given to individual household, and creates a workspace for the family within the building complex itself. Consequently, each cluster has two commercial floors with private workspaces at the periphery and co-working spaces in the core topped by three residential floors with individual households at the periphery and a community center and atrium in the core. The visible cluster boundary and dense centers uniformly distribute familial and economic spaces across levels, creating a web of networking centers that effectively place education, healthcare, day-care, community centers, etc. at the heart of the functioning of clusters linked via bridges within a neighbourhood.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

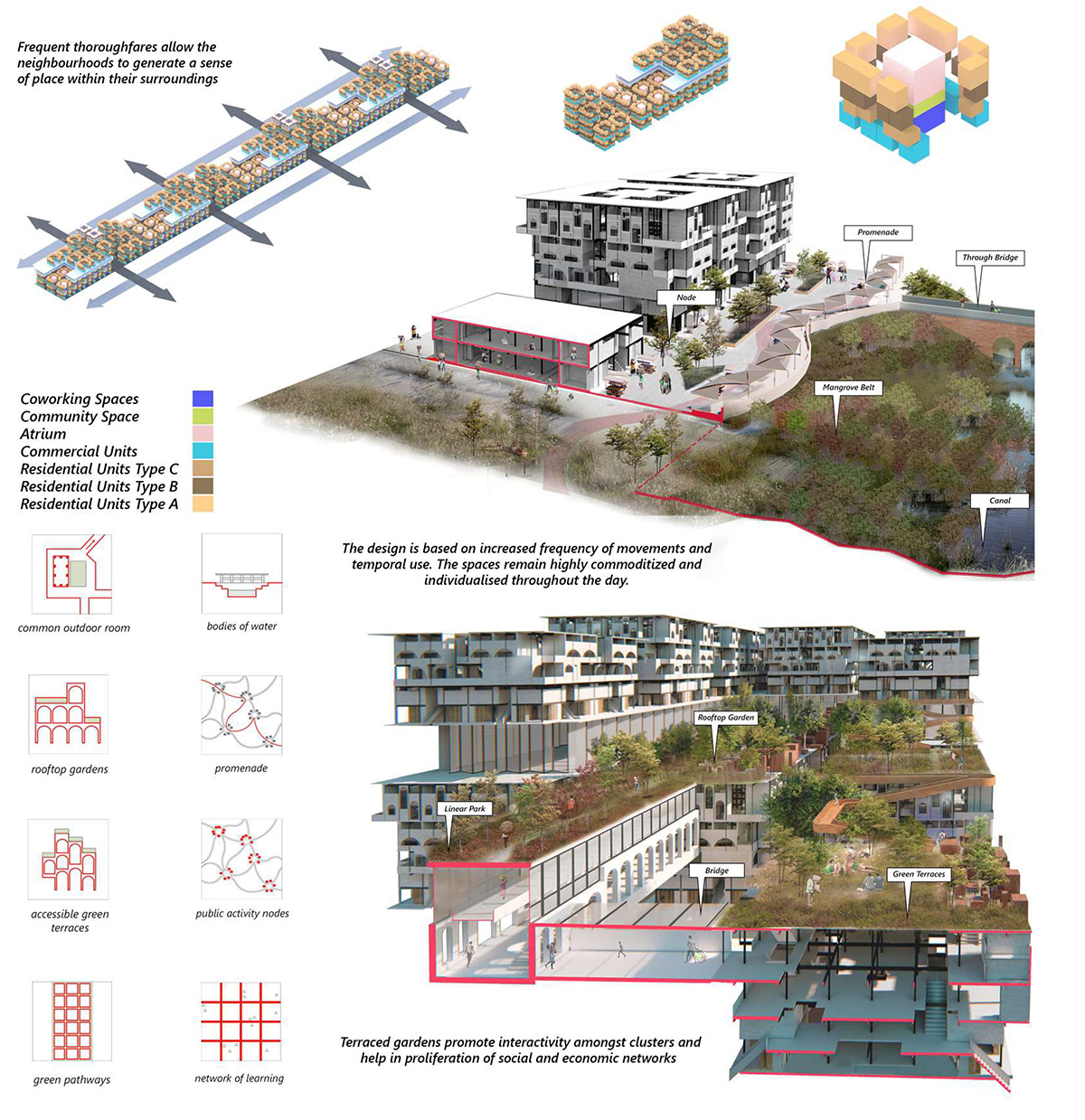

The design treats the 3.6 km long passive edges of Hindon canal and Shahdara drain to create a usable landscape, and along with commercial units placed on the ground, creates a marketplace with promenades that invite the surrounding fabric to interact, thereby, providing ground for informal socio-economic activities as well. Placement of bridges after regular intervals ensures interactivity between the two edges and establishes the design as a through-space that stays culturally relevant.

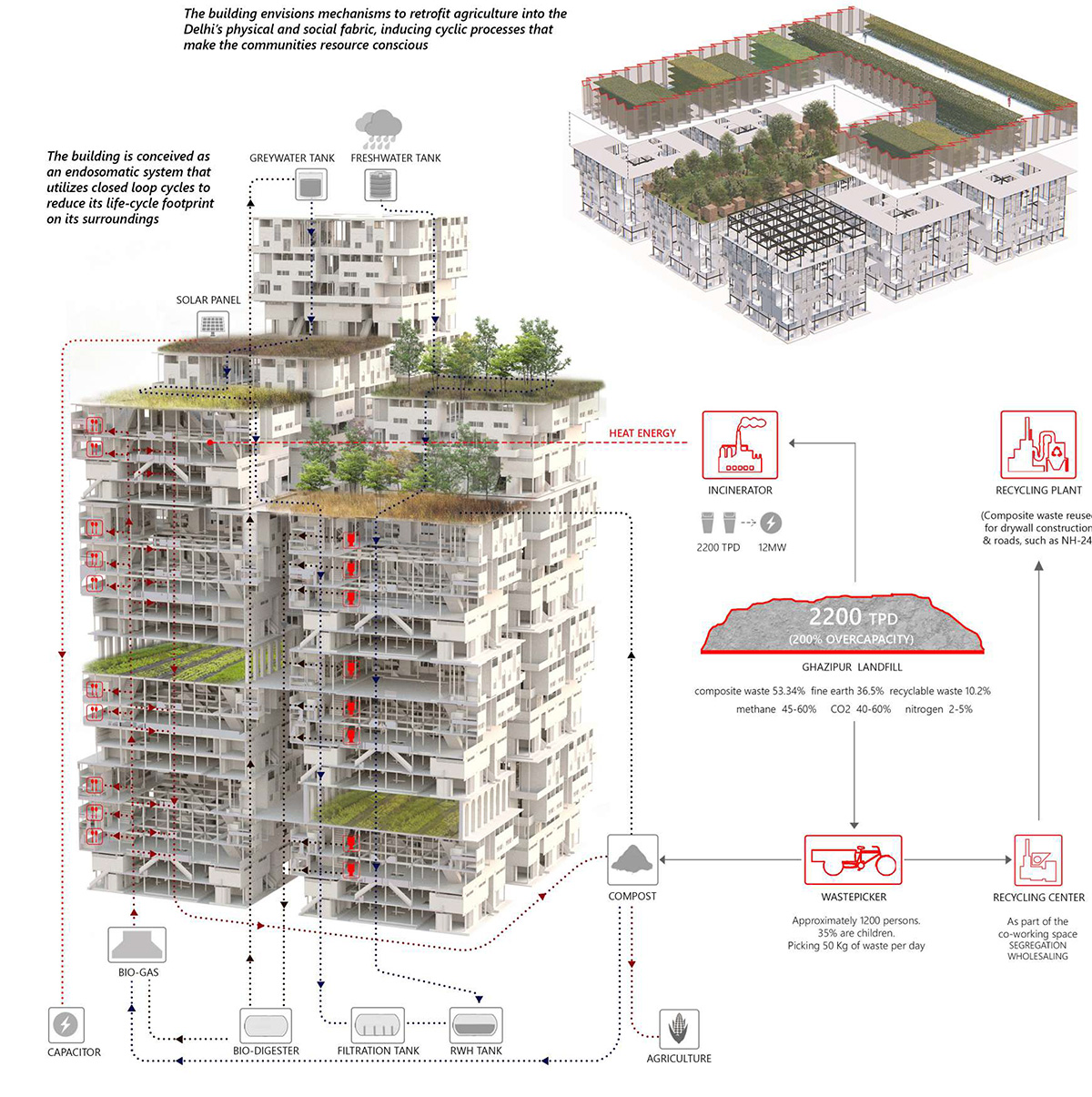

The building programme includes local marginal groups as stakeholders and occupants of the building system comprising roughly 10% of its total population, involving them in agriculture work in the landscape and hydroponics, trash segregation and recycling from Ghazipur, maintenance of terrace gardens and water-systems, cleaning of neighbourhood, street vending etc., thus, mainstreaming them into the society through revenue generation. Intermediate terraces, rooftop gardens and bridges create public spaces for recreation facilitating interconnectivity and increasing the degree of publicness of clusters to enhance women participation in this fragile system, creating a socio-economic structure based on parity; thus leveraging the concept of work-dwell communities.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

Tarun Bhasin: Considering that it is one of the most polluted sites in the city and represents one of the most environmentally disastrous and socially undesired contexts in the nation; how do you go about approaching such a scenario?

Yug Aggarwal: The quest for sustenance, sustainability, and acceptability is fundamentally based on reinventing the resource cycles on site. To put it in three simplistic words, our mantra was to - Abstain, Repurpose, and Optimize.

Delhi’s landscape is characteristic of channels carrying refuse polluting its primary freshwater source – the river – to a degree that it is unfit for human consumption. For that reason, it is imperative for the structure to have its closed-loop water cycle, with the effort of remaining neutral. Thus, the greywater from showers and kitchen is used for WCs. The blackwater from WCs is taken to bio-digesters that remove the black sludge from the greywater which is further utilized for rooftop gardening. The terraced roof system uses drip irrigation for effective watering of plants, also providing a channel for rainwater harvesting.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

The land that is good for crops is also good for the construction of buildings and in cities buildings triumph. Thus, the production of food in the wake of dying availability of land is not an issue of maintaining industrial capacity, but one of dealing with the displacement of farmers. A double-height volume comprises one of the floors in-between the entire building mass, dedicated solely to the placement of hydroponic infrastructure for food production, thereby, leveraging modern technology with the capacity to produce up to 50 times the value of traditional farming methodologies. Hydroponics isn’t just a means for sustenance but social entrepreneurship, through which displaced farmers are given skill training and repurposed into the future city food cycle of the city.

Biodegradable waste from kitchens, landfill site, and black sludge from bio-digesters are used to produce biogas that fires the stoves of each household. The remaining slurry from the biogas chamber is further used for composting, creating a closed cycle for organic materials as well. Provision for central heating during winters is insured via the utilization of methane from Ghazipur dump-yard by an incineration facility. Daylight and ventilation in households and communes are optimized by use of decks, wells, and punctured courts, supplemented by the use of solar PVs and capacitors that make the building energy efficient.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

Tarun Bhasin: That tackles the idea of sustainability at a built-scale only. But, how do the design and planning take on the challenges proposed by the entire landscape to reduce the inherent vulnerabilities of the site?

Yug Aggarwal: The interventions are obvious and that is why most-often ignored. The idea is to support the perennial culture that already exists on the site by strengthening the socio-natural relationships of the two most prominent actors of the landscape - the peasants and the birds.

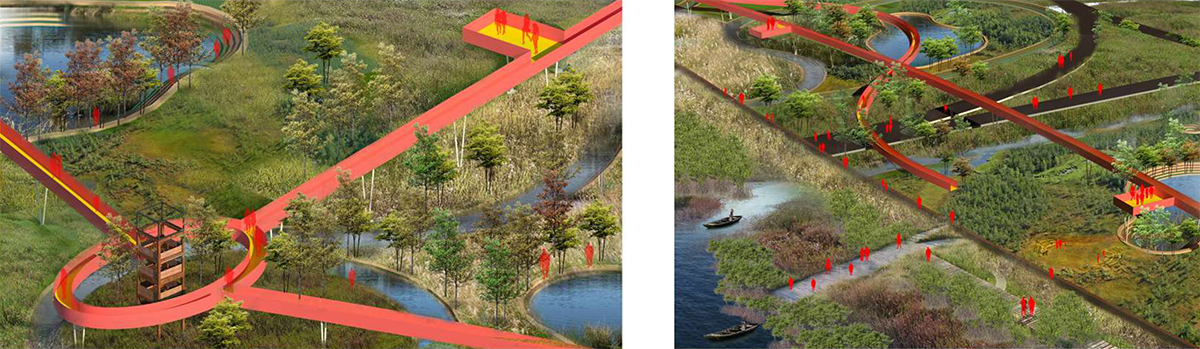

The blackwater from sewers is usually drained out into the Yamuna without any significant treatment, thus, damaging the riverfront and the nearby Okhla Bird sanctuary. The design of the landscape suggests the treatment of sewerage canal in all moments between the building to the river, by creating a system of wetlands that act as a barrier to seasonal flooding of the river while doubling up as effective public spaces during the dry season.

The water from Shahdara drain is mixed with Hindon Canal for oxygenation which is then flushed in the landscape that has many winding canals marked by mangrove plantations on both sides. The roots of the mangroves help filter garbage, heavy particles and metals, making the water safe for irrigation. This eutrophic water is channeled into the crop fields and parks for harvesting. The surface run-off from the fields is collected in the freshwater lakes at the centre of the field after effective absorption of all particulate matter, for groundwater recharge, thus, forming a closed-loop water cycle between the canals and Yamuna.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

The mangroves and trees that line the canal create long winding corridors that are extended from Okhla Bird Sanctuary and into the promenades along with the building complex. This helps in greenfield development wherein the vegetation facilitates the habitat and catalyzes the movement of keystone species of birds back into the city fabric, boosting local ecology.

The wisdom of the landscape of any geography is preserved in its peasant culture that protects and maintains its local ecology. Taking note, the design formalizes the position of agriculture and fisheries in the city culture by using the farms for rootzone treatment of water, and fisheries as freshwater sources. It places cycling tracks, nature trails, kayaks, boardwalks, bird watching towers, amphitheaters, and parks to project them as recreation and tourist spaces that invite people from across the city to venture in and experience it. This creates an inclusive urban-rural hybrid riverfront development that conserves the local ingenuity and rationalizes the city’s need for a public landscape memory.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

Tarun Bhasin: How do the interventions proposed at this site, expand and culminate into a holistic masterplan for the entire city? Is there an underlying pattern which grants this idea the benefit to be enacted upon as the basis for a masterplan?

Yug Aggarwal: The Yamuna riverfront meets with 19 major sewerage arteries along its 46km long passage in Delhi. All these nodes have reserved forest areas, ecological zones and freshwater sources in their vicinity. The proposal through its landscape design works throughout the length of Delhi’s sewerage systems to suggest methods to mainstream their edges, utilize vacant land on their periphery, and act on the point where they meet the river to effectively treat water. Therefore, the design proposal can be taken as a blueprint to restore the disturbed local ecologies along the length of Yamuna to create one cohesive environmental fabric for the city, that infiltrates its physical fabric through greenfield development along the length of drain channels.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

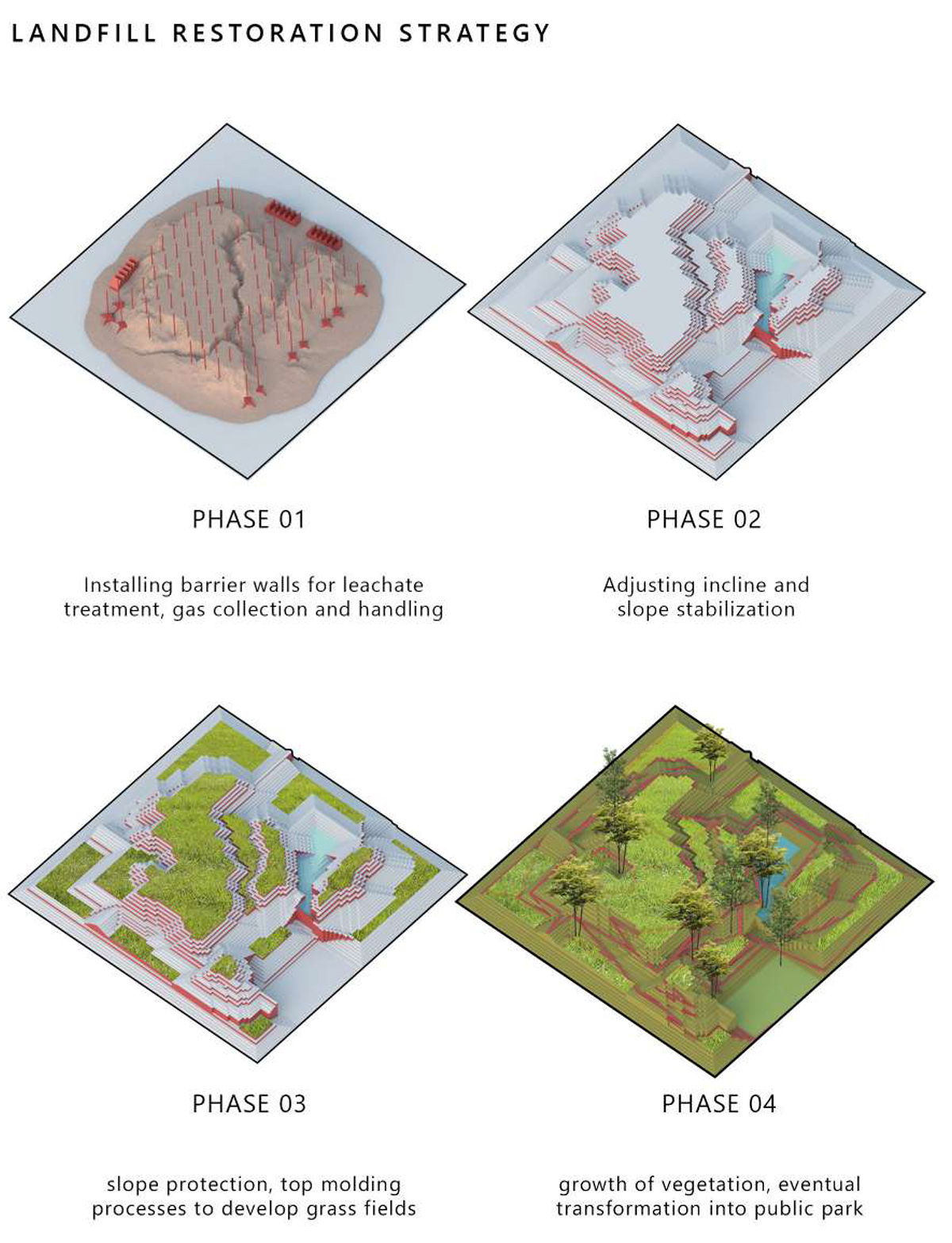

By employing marginalised local workers and formalizing the economic infrastructure that exists at Ghazipur landfill site, the design incorporates material reuse and recycling methodologies as an integral part of its maintenance and operations lifecycle. Moreover, it helps in development, incentivization, and proliferation of such economies by providing incubation centers within the built mass for spatial development and networking of communities involved in the work. As a result, by recycling and incineration of all biodegradable, non-biodegradable and non-recyclable waste – the proposal seeks to reduce the footprint of Ghazhipur landfill and other major landfills of Delhi. It employs Leachate treatment of the site, followed by embanking, soil stabilization and greening to turn the site into a series of hills and parks over a couple of decades to turn it into public memory.

The design vision and interventions are impregnated by the idea of reviving city memory along its urban fringes, generation of active public spaces and marketplaces, creation of work-dwell communities that provide shelter and livelihood to marginalised people, ensure gender-parity and transgress social boundaries – all of it to redefine the social processes of the city and redraw the masterplan of Delhi by utilizing the bottom-up processes as an integral part of city-wide infrastructure and identity.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

Tarun Bhasin: Have you tried to pitch your ideas for realization? Have you received any positive response in this direction?

Yug Aggarwal: We recently presented our proposal at The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs in New Delhi. They liked our concepts and asked us to develop the proposal in detail on a few chosen agendas from the bouquet we explored for the competition. Moving forward, we are in talks with some NGOs working on parts and parcels on the issues that represent the underlying themes of the proposal, and some site engineers who have been working on cleaning of the drain and landfills. Our idea is to develop a holistic plan for a pilot project that can be run on part of the site. In the coming year, we seek to develop a financial action plan for the entire concept that can act as a module for similar sites. We are in talks to get such an idea implemented through the Delhi Government, under a public-private partnership and are also in talks to see the viability of the entire programme to be incorporated in the Smart City Mission.

We feel that issues such as waste, water, biodiversity, access, social inclusion, opportunity, and livelihood cannot be treated as isolated issues in our city anymore. They are interconnected and our masterplans must acknowledge the presence of underlying systems and their stakeholders for equitable future development and growth to achieve the notions of sustainability. And we, as architects, hope to find more solutions to drive those notions forward.

Image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019

The Jury Comments from the competition are as follows:

Dr. Nirmal Kishnani: The relocation of marginalised communities is the focus, with a new kind of riverfront development in which the question of waste is explored. Slums in India often rely on rivers as waste disposal systems. In this proposal, this is mitigated with a layer of mangroves that cleanses wastewater as it leaves the settlement. A landfill site nearby is restored as a bird sanctuary.

Ada Fung: This mixed-use linear development between a canal and a drain offers an opportunity for marginalised societies in Delhi to act as primary stakeholders, engaging them to help treat sewage water, resolve problems with landfill, mainstream agriculture, and fisheries, etc., with a story of remediation.

Dr. Jalel Sager: This project has an admirable programme for remediation of polluted land. Its structural and social programme could be interesting if implemented with care, as could the half-finished pedestrian bridges above the wetlands. Much of this ambitious project would be contingent on implementation.

Top image courtesy of FuturArc Prize 2019.

> via FuturArc Prize 2019