Submitted by Anju George

Reclaiming back the spaces that belong to all of us: Placemaking in the urban context

Canada Architecture News - Aug 04, 2019 - 00:40 13561 views

I was pondering the theme for my next article when the video of the pink seesaws installed across the US-Mexico slatted border cropped up on my Twitter feed. I knew I wanted this write-up to reflect the gratitude I had for Mr. Ronald and Ms. Vanessa, the design champions behind this humane intervention. This write-up is very much a continuation of what I had addressed in my previous article, but with a special focus on the impact public spaces have on communities.

Canadian cities need to very well be benchmarks for other cities around the world, predominantly because of the extremely high rates of immigration. Canada’s population grew by 168,687 in the second quarter of 2018, of which 82 per cent, or 138,978, was attributed to international migration1.

Open spaces that are accessible, yet congenial, form a very important part of social infrastructure. They are the panacea for rooted social ills such as segregation, exclusion and gentrification. The development of such spaces engenders the creation of equitable environments. The public realm becomes a space where people exchange ideas and confront one another. Racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, and ageism often result in exclusion from, and/or discrimination in, public spaces2. However, meeting and communicating in open spaces, can be a platform for breaking up social segregation, and therefore public places become indispensable for establishing contacts3. We should fashion the public realm to be sufficiently intimate, yet inclusive for all. Design interventions are the key to making that happen by breaking prejudices and barriers. This is where tactical urbanism comes into effect. We need to be asking the right questions. Who owns these lands? How much of decision making is left to the real estate developer? Can we change the status quo and get citizens to participate in the designs of their neighbourhoods? Are participatory public charrettes ever held?

Frederick Law Olmsted, the much-regarded landscape architect and planner, is to parks, as much as Charles Babbage is to the digital computer. What ran on in his mind when he got around to designing parks in North America? He believed that the built environment had the ability to promote democratic values4. If the concept of "placemaking" needs to be incorporated into already moulded architecture, it necessitates major retrofitting that will involve a great deal of budgeting and finance. What if we were to design new spaces around these already built environs that not only advocate the approach of placemaking, but very much employ its aspects? How can we program spaces that surround the built environments to be inclusive? The retrofits required to do so are likelier to be far cheaper and easier to do, yet considerable enough to impact the community in a more profound manner.

Longfellow Playground, South Bronx, New York - a city-wide effort to reinvest in the open spaces serving low-income neighbourhoods. Image © NYC Water.

Inclusion efforts at the intersection of public space and public health should focus on populations and neighborhoods that have experienced disenfranchisement and disinvestment5. Populations exposed to the greenest environments have the lowest levels of income-related health inequality, reiterating the fact that physical environments that promote healthy living standards may actually aid in reducing socio-economic health inequalities6.

It is very important thus to know the community for which you are creating your public realm for. That is what builds both context and identity. Everyone should feel represented in his or her community. It is upto planning practitioners and professionals to make this a requirement, thereby informing good design. Surveys should be administered in schools and workplaces to find out the make-up of the population being served by the soon-to-be developed community.

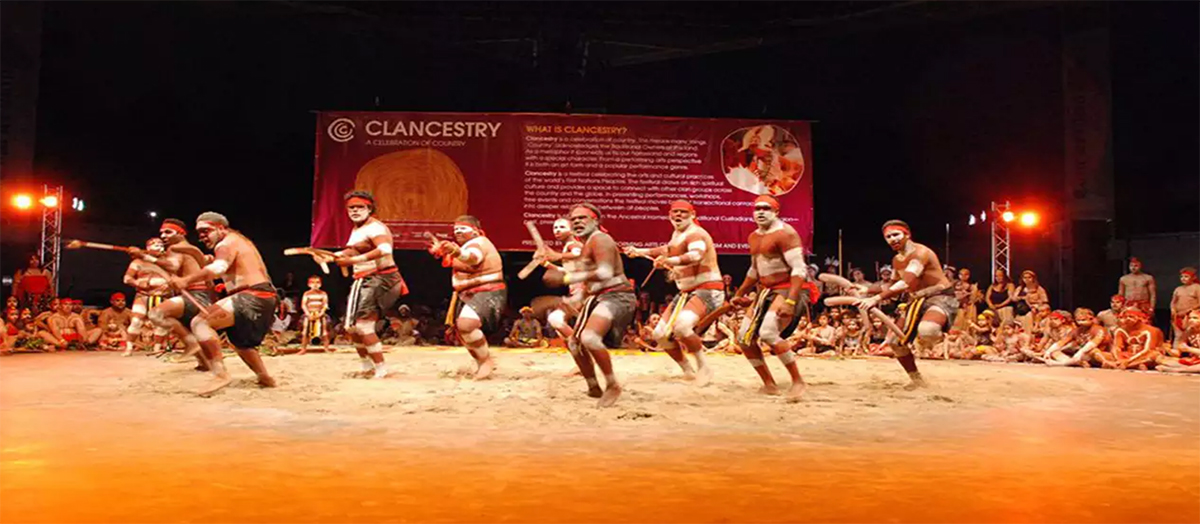

Inclusive festival representing Indigenous peoples in South Bank, Brisbane. Image © corymbia.

We often tend to forget how essential it is for the physical space or the community at large to adapt with time. Spaces that adapt to changing needs, and communities that can assess their own needs as they change, fit like a glove, materializing in lasting benefits of inclusionary processes7. To perceive and come to respect unfamiliar gender roles and develop bonds that cross the boundaries of ethnicity, nationality and creed, youths should come face to face with their peers in surroundings that are accessible to members of all communities, without formal, financial or symbolic restrictions8.

Uganda's Slum Festival themed on the environment. Image © Street Angels Uganda.

Examples of inclusion adopted in public realms are growing by the day. Alberta brought to the forefront an inclusion plan for its parks which is "a commitment that everyone is welcome in Alberta’s parks – and that everyone belongs outside"9.

Adaptive accessibility introduced in all of Alberta's parks. Image © Alberta Parks.

For years, Folkets Park or People’s Park in Nørrebro, Copenhagen, has been the hotspot of political protests, gang violence and drug commerce, and has remained a nuisance to Copenhagen’s municipal government10. The organizers of the park decided to reinvigorate the space and made it a point to be inclusive. That is when Balfelt, a Danish artist, came on the scene. His main priority was to invoke a sense of inclusivity through his art.

Active community design at Folkets Park, Copenhagen. Image © Steven Johnson (Boundless).

Clarency Festival involving the indigenous community at South Bank, Brisbane. Image © Sarah Ward's article.

Despite Medellin’s infamous history of violence, it has become the posterchild for its avante-garde efforts to employ public spaces as tools to improve the quality of life. Biblioteca España (Spain Library Park), designed by Giancarlo Mazzanti, was part of the Mayor’s plan to get rid of social exclusion by promoting social integration and revitalizing low-income areas.

Parque-Biblioteca-España, Medellín, Colombia. Image © Sergio Gómez

In Shenandoah National Park, there stands a poster that reads "Find Your Park". It is upto the visitor to experience the park in a way he or she finds fit. The US National Park Service is launching several schemes to get rid of the social ills that are very much still predominant in the society.

Walkway provides visitors with an unhindered view of the desert in Badlands National Park, South Dakota. Image © Stephen John (National Geographic).

As the UN Habitat, 2015 postulates, public spaces enhance one’s health owing to a better quality of life. They also help in promoting income, equity and social inclusion, which in turn are instrumental in creating gender and age-friendly cities. To top it all, a well-designed space enhances public safety. The 11th Sustainable Development Goal also prioritizes the public open space to help achieve safe and resilient cities.

Getting women to use parks is a whole different, yet critical conversation that needs to be brought to the table. Women need to feel safe. Lighting design within parks should be made mandatory. Clean restrooms should also be a requirement. Penalties should be imposed on those who don’t do their bit to leave it spotless.

Placemaking elements such as hammocks at Einsiedler Park, Vienna. Image © Zdenka Lammelova.

Platforms to sit and chat within St. Johanns Park, Basel. Image © www.wien.gv.at.

Transportation to and from public parks should also be thought out. The choice of transit should be made available. Wide sidewalks, accessible public transit stops, are some of the interventions that can be introduced to make everyone feel welcome. Older people, who find it difficult to drive or walk unaided, may actually think of using the newly renovated space. Graphic signages or signs in popular languages along with information flyers should be made available. The next barrier to people feeling excluded is associated with affordability. There should be measures to see that this barrier is lifted for people who are otherwise marginalized.

How about we incorporate these principles while developing a retrofitting plan, thereby making the place more alluring? The public realm doesn’t have to be static. Elements of the public realm can be converted into grounds for live events and festivals that bring different sections and strata of the community together. The arts too very much have the capacity to unite persons belonging to varying spheres within their societies. Cultural festivals are public celebrations that demonstrate community values, reinforce community pride and instill a sense of place11. Exhibitions portraying the heritage and cultures of different peoples who live in the area can be used as the neighbourhood’s enticing tool.

Community outdoor yoga at Church Street Marketplace in Burlington, Vermont. Image © Church Street Market Place.

Canadian cities are starting to do their bit. The Indigenous Art Park in Edmonton, Alberta, is the outcome of that very effort. ᐄᓃᐤ (ÎNÎW) River Lot 11, pronounced ee-nu, the brainchild of Indigenous artists, Métis Nation of Alberta and the Confederacy of Treaty No. 6 First Nations and the city, is a public space that showcases the creativity of Indigenous artists12. The area, which is perched within the Queen Elizabeth Park, has permanent installations that include sculptures, colourful mosaic stone turtles and a piece embedded with large Cree syllabics13. The park site has also been so carefully chosen that it perfectly situates itself amidst a rich history with the Walterdale Bridge, the Fort Edmonton grave site, traditional burial grounds and a historic reserve a couple of kilometres away14.

Mural at Indigenous Art Park, Edmonton, Alberta (Depiction:. Preparing to cross the Sacred River). Image © Brad Crowfoot Photography.

As cities grow and densify, access to carefully designed attractive public spaces has become very much an important asset, but has also become challenging for the poor, minorities and vulnerable groups to feel welcome15. A certain potential is reflected within placemaking that doesn’t need to foreclose certain populations’ access to accommodate others, which triggers us planners and citizens to help design the public realm keeping social cohesion in mind16.

Canada's indigenous communities attending a public event. Image © Levon Suvunts' article.

References:

1Smith, Stephen. “International Migration to Canada reached Record Levels in Second Quarter of 2018.”

2Metropolis, World Association of the Major Metropolises Women in Cities International. “Safety and public space: Mapping metropolitan gender policies.”

3Seeland, Klaus et al. “Making friends in Zurich's urban forests and parks: The role of public green space for social inclusion of youths from different cultures.”

4Roulier, Scott. “Frederick Law Olmsted Democracy by Design”

5Gehl Institute. “Inclusive Healthy Places”

6Mitchell, Richard and Popham, Frank. “Effect of Exposure to Natural Environment on Health Inequalities.”

7Gehl Institute. “Inclusive Healthy Places”

8Seeland, Klaus et al. “Making friends in Zurich's urban forests and parks: The role of public green space for social inclusion of youths from different cultures.”

9Alberta Parks, Alberta Government. “Alberta’s Plan for Parks: Inclusion Plan”

10Tholl, Sofie. “In Copenhagen, a “People’s Park” Design Includes Dark Corners.”

11CIDCO Smart City Lab at NIUA. “CIDCO @ Smart Newsletter”

12Lievatt, Kieran. “Edmonton’s Indigenous Art Park opens: ‘Everyone is welcome here’.”

13Lievatt, Kieran. “Edmonton’s Indigenous Art Park opens: ‘Everyone is welcome here’.”

14Lievatt, Kieran. “Edmonton’s Indigenous Art Park opens: ‘Everyone is welcome here’.”

15CIDCO Smart City Lab at NIUA. “CIDCO @ Smart Newsletter”

16Goyal, Vinita. “Creative placemaking' in San Francisco and Seattle: democratic and/or inclusive?”

Top Cover Image: Use of Active Public Space in St. Lawrence Market, Toronto. Image © St. Lawrence Market.