Submitted by WA Contents

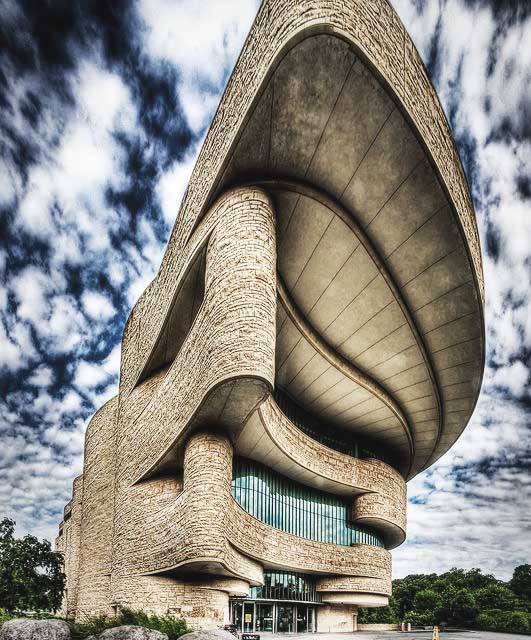

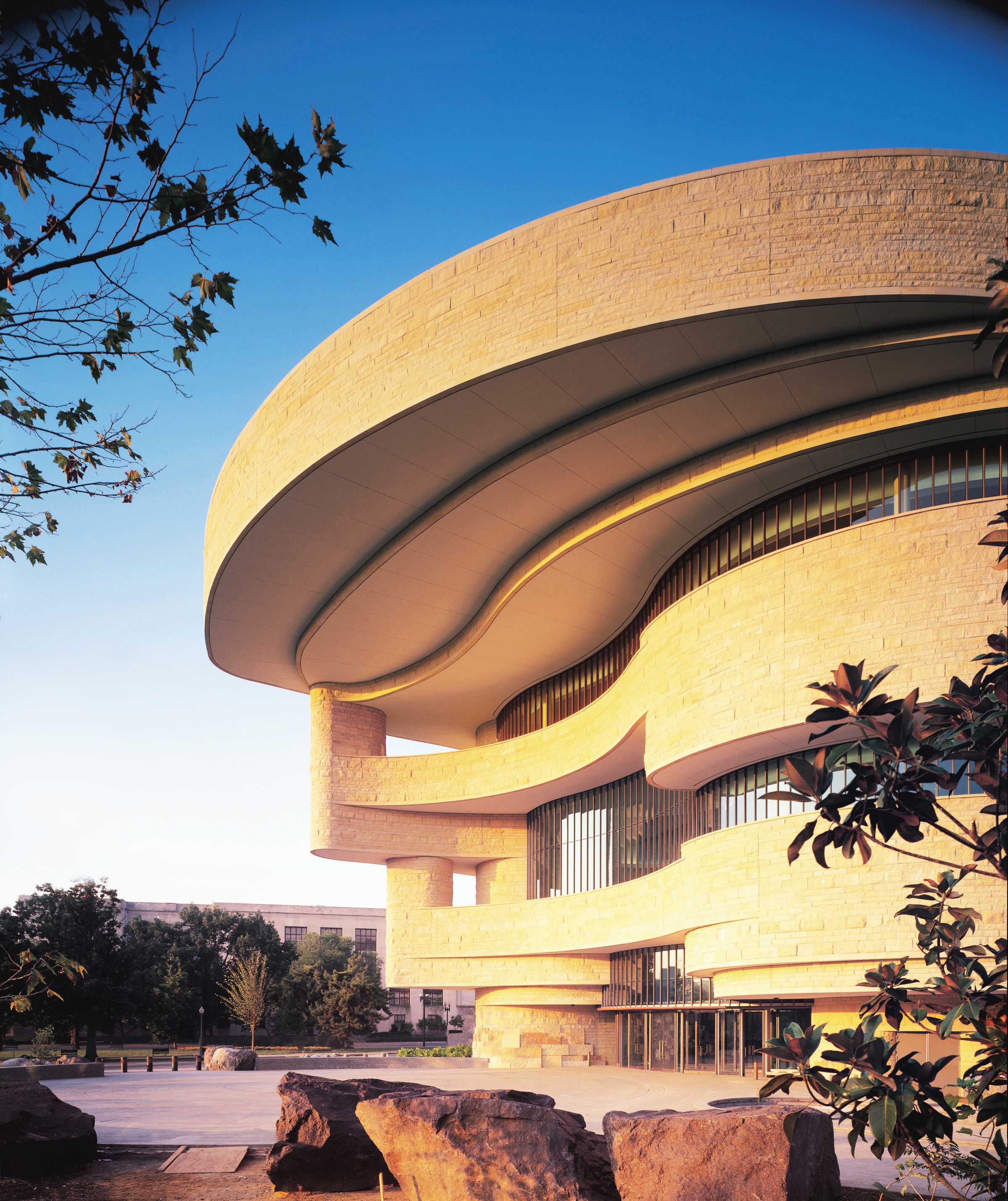

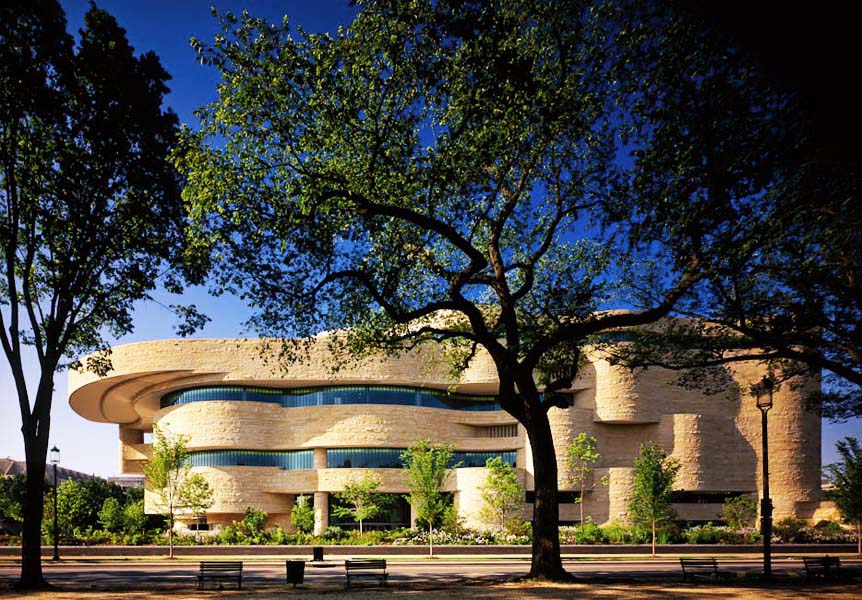

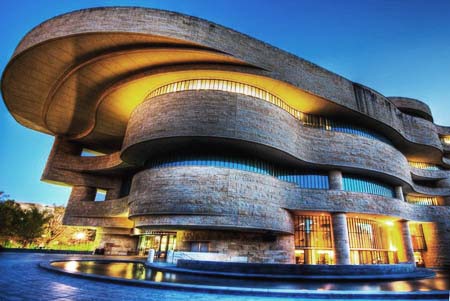

National Museum of the American Indian

United Kingdom Architecture News - Jul 22, 2014 - 13:17 21555 views

Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC.Image:Pinterest/Gian Franco Ferre

Beginning in the early 1990s, the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) opened dialogues with Native communities and individuals across the Western Hemisphere. These early meetings resulted in the museum's landmark document The Way of the People (1993), which reached beyond the basic requirements of the building to incorporate Native sensibilities throughout the museum building.

A series of themes emerged from the dialogues. One involved the intuitive nature of the building: it needed to be a living museum, neither formal nor quiet, located in close proximity to nature. Another was that the building's design should make specific celestial references, such as an east-facing main entrance and a dome that opens to the sky. Many comments expressed the desire to bring Native stories forward through the representation and interpretation of Indian cultures as living phenomena throughout the hemisphere. Some basic parameters for the building structure were dictated by the 4.25-acre trapezoidal site, the building restrictions for the National Mall, and an active creek bed flowing below the site. These challenges were addressed initially by the design team of GBQC and Douglas Cardinal, Ltd., which included consultants Douglas Cardinal (Blackfoot), Johnpaul Jones (Cherokee/Choctaw), Donna House (Diné/Oneida), and Ramona Sakiestewa (Hopi).

Photo: © 2004 Judy Davis/Hoachlander Davis Photography for Smithsonian

The building’s distinctive curvilinear form, evoking a wind-sculpted rock formation, grew out of this early work, forming the basis for the architecture. Following this conceptual design work, the project was further developed by Jones, House, and Sakiestewa, along with the architecture firms Jones & Jones, SmithGroup in collaboration with Lou Weller (Caddo) and the Native American Design Collaborative, and Polshek Partnership Architects. This extended collaboration resulted in a building and site rich with imagery, connections to the earth, and layers of meaning. The building is aligned perfectly to the cardinal directions and the center point of the Capitol dome, and filled with details, colors, and textures that reflect the Native universe.

Image:aviewoncities.com

The Native Landscape

Native people believe that the earth remembers the experiences of past generations. The National Museum of the American Indian recognizes the importance of indigenous peoples’ connection to the land; the grounds surrounding the building are considered an extension of the building and a vital part of the museum as a whole. By recalling the natural environment that existed prior to European contact, the museum’s landscape design embodies a theme that runs central to the NMAI—that of returning to a Native place. Four hundred years ago, the Chesapeake Bay region abounded in forests, wetlands, meadows, and Algonquian peoples’ croplands. The NMAI restores these environments and is home to more than 27,000 trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants representing 145 species.

Image:maxwellmackenzie.com

Hardwood Forest

The grouping of trees, plants, and shrubs on the museum’s north side is known as an upland hardwood forest. The more than 30 species of trees reflect the dense forests that exist in the Blue Ridge Mountains along the Potomac River, and elsewhere. Forests have provided Native communities with important materials for shelter, food, and medicine, among other purposes, including Eastern red cedar, staghorn sumac, and white oak.

Wetlands

Culturally significant to many tribes, wetlands are rich, biologically diverse environments. The museum’s diverse wetlands area—and the ducks, squirrels, and dragonflies that make it their home—represent the original Chesapeake Bay environment prior to European settlement. Chesapeake means “Great Shellfish Bay” in the Algonquian language. River birch, swamp milkweed, pond lilies, silky willow, and wild rice abounded in the dense marshes, as they do in the museum’s natural habitat.

Meadow

The museum’s meadow environment consists of abundant grasses, wildflowers, and shrubs, including buttercups, fall panic grass, and black-eyed Susans. Meadows are important sources of medicinal plants used by traditional healers, who give thanks for plants through an offering of tobacco, song, and prayer. Plants are considered by some tribes to be the hairs of Mother Earth, and one must express appreciation when taking them from the soil.

Image:architecture.desktopnexus.com

Traditional Croplands

About 60 percent of the world’s diet today is derived from Native American foods, such as potatoes, chilies, tomatoes, and even chocolate. The museum’s traditional croplands incorporate the irrigation and planting techniques of Native peoples that revolutionized agriculture around the world. The “Three Sisters” (ortres hermanas) plants—corn, beans, and squash—flourish in NMAI’s croplands, alongside lush tobacco plants. A popular museum event for all ages, the release of ladybugs throughout the summer provides a natural form of pest control.

Grandfather Rocks

Forty large uncarved rocks and boulders, called Grandfather Rocks, welcome visitors to the museum grounds and serve as reminders of the longevity of Native peoples’ relationships to the environment. The Grandfather Rocks, hewn by wind and water for millions of years, were selected from a quarry in Alma, Canada. The boulders were blessed in a special ceremony by the Montagnais First Nations group prior to their relocation to ensure that they would have a safe journey and carry the message and cultural memory of past generations to future generations. Upon arriving in Washington, the boulders were welcomed in a blessing led by Karenne Wood (Monacan).

Site Plan: Building, Gardens, and Plazas Illustration courtesy National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution

Cardinal Direction Markers

A subtle yet significant design concept, the museum’s Cardinal Direction Markers are four special stones placed on the museum grounds along the north-south and east-west axes. Those axes intersect at the center of the Potomac area of the museum building, linking the four directions to the circle of sandstone that marks the figurative heart of the museum. The four stones also honor the Native cultures of the north, south, east, and west. The stones have traveled from the far reaches of the hemisphere in collaboration with their Native source communities: Hawai’i (western stone); Northwest Territories, Canada (northern stone); Monocacy Valley, Maryland (eastern stone); and Puerto Williams, Chile (southern stone).

Source:nmai.si.edu