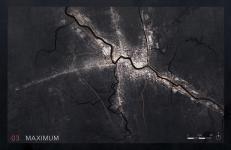

Youngstown was once a prosperous steel producing town, and a symbol of mid-century America's manufacturing prowess. Decades of shortsighted urban and infrastructural planning, combined with a severe lack of economic diversity, however, left the city particularly vulnerable to the forces of de-industrialization. Since its industrial peak in the late 1950's, the city has been rapidly shrinking in population and industrial output, yet its physical footprint, form, and infrastructures have not adjusted and "right-sized" to match the scale and needs of its current economy, population, and demographics. This design proposal, operating both urban and architectural scales, seeks to correct these imbalances through the removal of outmoded infrastructures and the reclamation, adaptation, and celebration of smaller, overlooked, or forgotten ones to promote a more appropriate, fine-grained urban expression.

2017

0000

01. SHRINKING CITY / INACCESSIBLE CITY

The steel plants which once powered the city’s economy and anchored its urban form are long gone, yet the sites where they stood along the Mahoning River remain barren, polluted, and sealed off from the outside. The surrounding urban fabric is littered with brownfield sites and faceless industrial parks, and fragmented by fences, railway yards, and limited access highways, built in the 1960's to bypass the city and its blight altogether. The result is a city with an increasingly sparse, under-served, and isolated population: one whose remaining economic opportunities are hermetically contained within bland, auto-centric, and mono-cultural industrial parks far from the historic city core, and the neighborhoods they aim to serve.

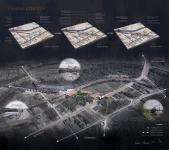

02. RE-WIRING AND "RIGHT-SIZING" THE CITY

The aggregation of “right-sized” interventions could promote a larger pattern of strategic “corridor-ization” at the scale of the city. Such urban re-structuring would allow for a denser, and more vibrant urban fabric-even with a continued trajectory of population arbitrage. One first step could be the phased removal of select stretches of highway. A targeted strategy of removing over-scaled and obstructive infrastructures, and subsequently re-claiming and promoting finer, “right-sized” ones could harness the city’s trajectory of contraction to encourage greater population densities along resilient, mixeduse, and pedestrian-oriented corridors. To test such a strategy, I propose the dismantling of a one-mile stretch of Interstate-680 through the centrally located, industrial neighborhood of Mahoning Commons, and explore a range of opportunities for “right-sized” infrastructural intervention presented by this removal, all of which aim to establish tighter links between the adjacent land uses.

03. SITE STRATEGY AND PHASING

A de-commissioned, elevated rail trestle, which currently cuts through Mahoning Commons, could function as a prominent and vibrant confluence within the city’s new network of denser urban corridors. This proposition would first seek to establish a pedestrian and streetscape link between formerly inaccessible industrial parks along

the river and their adjacent, under-served residential communities. Such a link might subsequently grow into an urban destination in its own right through the sensitive integration of commercial, industrial, residential, and public spaces along the corridor, with the fabric of the surrounding neighborhood and existing streetscape.

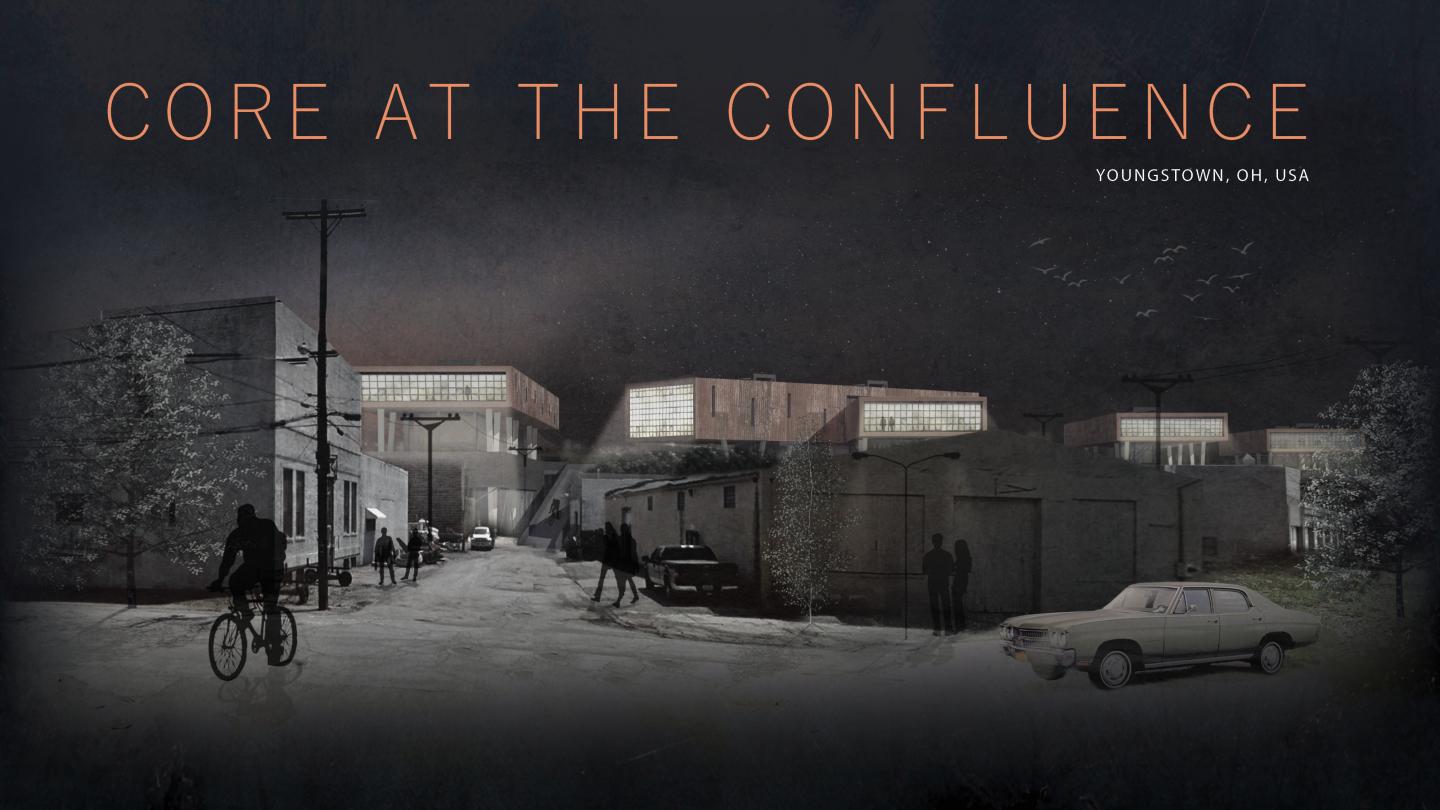

04. ARCHITECTURAL ARTICULATION

The architecture of a vibrant urban confluence might be articulated as a conversation with its surrounding post-industrial context: drawing upon a vernacular palette of cast-in-place concrete with slag-based aggregate, and corrugated metal cladding with a weathered patina finish. Industrial and commercial programs would be sited so as to infill needed density along Marshall Street, Mahoning Avenue, and Tod Avenue, and would be built into the existing topographical relief along the trestle so that their roofs might function as public extensions of the newly “found” elevated streetscape. Residences would hover above this new streetscape: shielded from the industrial and commercial activity below, yet never disconnected from it. Commercial and industrial structures would maintain a strategy of multiple frontages, with loading and industrial access zones facing away from the new pedestrian-oriented streetscape, and public entrances facing toward it. The topography of the new “found” streetscape would alternately rise to merge with the historic trestle, and then fall away to reveal it: suggesting a hierarchical order where existing industrial infrastructure, ground, and neighborhood context take precedence over architectural intervention.