In 1998 the Wexner Center for the Arts in Ohio joined with SFMOMA and NYMOMA in a three museum exhibition and debate examining the intersection of new conceptual design ideas with the burgeoning new capacity to construct objects which, so often in the past, could only be imagined.

The divide that separated visionary architecture from the technical capacity to realize those visions, from Gaudi and Mendelsohn to Lebbeus Woods, seemed, suddenly to be narrowing. Now, the hypothesis went, if you could see it in your head, you could deliver it on the site. And the premise of that exhibit and the surrounding discourse has clearly been confirmed in the recent construction of building ideas that once came to life only in drawing.

The Wexner Center in Columbus was designed by New York architect Peter Eisenman as an admixture of an historic, largely masonry structure, and an exhaustive examination of the organization prospects of the steel grid, as the new building addition. The orthogonal system – the grid as conceptual premise in architecture and city planning - runs backwards for millennia, with landmark stops from Hippodamus at Miletus, the first gridded city plan, to the Park Avenue Lever House and Seagram buildings.

The Wexner addition is the architect’s effort to finally exhaust the promise of the grid as an ordering and space making mechanism. The galleries present the grid as floor, as wall, as roof, as glazing system, and as lighting, and structure. But there was more: the tilted grid, the bent grid, the folded grid. Grids uber alles.

The Moss office in its installation offered the Wexner an entirely different perceptual and space making option. The grid qua grid is centerless, a conceptual neutrality that theoretically extends in every direction, endless, and without a focus.

The Moss alternative examined a contrary ordering mechanism, the curve. The curve suggests a different spatial prospect - the possibility of center. So in the lexicon of shapes, no matter how sophisticated the discussion of intricate geometries, the essential juxtaposition is centered and centerlessness.

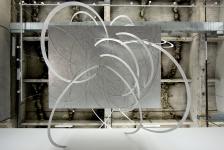

Moss built the missing center in the Wexner, supplying the geometric opportunity {intentionally} omitted from the original architect’s design. We called that foreign vantage point the Dancing Bleachers.

The attenuated steel legs – the ribbons - tenuously attached to floor and roof, suggested a concentric order of seats arranged around an implied center. The Moss exhibit at the Wexner implied a spatial center, and simultaneously, a center for advocates to debate, surrounded by a seated group of participants. Hyde Park at the Wexner.

The Wexner exhibit constructed that prospect of a center for debate, surrounded by the studied manifestations of gridded neutrality.

Not long after the three-museum exhibition, the Moss office was invited to design a high rise structure in Los Angeles at the corner of la Cienega Boulevard and Jefferson Avenue, adjacent to a long anticipated surface rail stop intended to connect the Westside of Los Angeles with downtown. The site is located in the south-central portion of Los Angeles in a poor, minority area, well known for two race riots, but for little else - left dormant for years as various other parts of the city were re-developed.

The high rise project was designed, applying the antithetical grid premise first used in the Dancing Bleachers. The tower buildings – there were initially two – were designed without the conventional orthogonal order of columns and beams, but were rather supported with a dense, curvilinear order of ribbons, neither beams nor columns, that densely circumscribed and supported the building.

The Moss office received final planning and design approval from the City of Los Angeles in 2008 to construct the high rise, now a single tower, that will adjoin the downtown to the Westside surface rail route currently under construction.

The tower is

2009

2009

.jpg)