Submitted by WA Contents

A night with the Bauhaus ghosts

United Kingdom Architecture News - Jan 08, 2014 - 11:46 7373 views

The parties lasted for days, the students slept with tutors – and their sleek designs changed the world. As modernism's most famous school reopens, Oliver Wainwright books a room

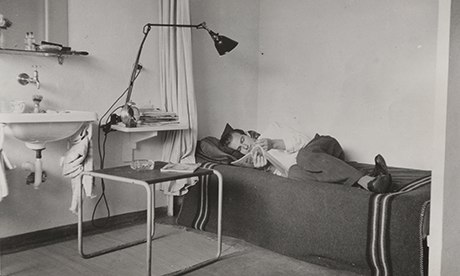

Haus party … students at the Bauhaus in 1931. Photograph: Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

A single tube light hangs above a utilitarian sink, casting a ghostly pallor across the blood red lino. Two simple chairs, bent from tubular steel, sit below a picture window that stretches the full width of the room, while a black Bakelite lampshade dangles above the bed from a long mechanical arm. The sound of coughing echoes down the corridor from the communal showers, as the plumbing clangs into action. I'm staying a night in the Bauhaus, the crucible of sleek 20th-century design – but it feels more like an East German youth hostel.

"We wanted to return the rooms to how the students would have encountered them," says Wolfgang Thöner, head of the collection at theBauhaus Foundation in Dessau, which has just reopened the school's accommodation block to paying guests in search of the authentic Bauhäusler experience, from €35 for a single room. "Thankfully," adds Thöner, "you don't have to walk down to the basement to have a shower any more – and the beds are a bit more comfortable."

When the Bauhaus opened here in 1925, having been hounded out ofits first home in Weimar by the Nazis, the concrete and glass complex was a startling vision of modernity. With its three-storey curtain wall wrapping around the workshop building, connected by a bridge to a wing of classrooms and a bright white block of bedrooms, it rose out of the fields on the edge of this small industrial town as dazzling beacon, ringed by cruise-liner balconies. In the words of its architect and founding director, Walter Gropius, who conceived the school as a collective guild of modern craftsmen, it represented "the crystal symbol of a new faith".

The exterior of the Bauhaus in Dessau, with its distinctive balconies. Photograph: Yvonne Tenschert

For the next six years, before it was closed down once again by the Nazis and moved to Berlin for one final futile year, this small crafts college (of only 200 students at any one time) produced some of the most influential objects of all time. Just as the curtain walling and strip windows of the building have since been imitated in everything from office blocks to luxury villas, so too have the functional, streamlined forms of the work made within its walls pervaded far and wide. The steel furniture and lighting from the workshop, the bold block patterns from the textile department and the experimental graphics from the printing press can all find their descendants in today's designs – not to mention the school's bestselling product (perhaps ironically for an institution that espoused "truth to materials"): its collection of patterned wallpaper.

The work has been so influential, in fact, that staying the night in a Bauhaus bedroom, almost 90 years after it welcomed its first students, feels a bit like having a sleepover in an Ikea room set and being haunted by ancestral relics of the flatpack. A nest of coloured tables stands in one corner, almost identical to ones you can buy at Habitat. Closer inspection reveals they are the work of Josef Albers, who ran the foundation course here, and whose bedroom it turns out I am staying in – complete with the bookshelves he designed for Gropius's own office.

Next to the sink, long lengths of tubular steel rise from the floor in smooth curves, bending into the form of a coatstand. I think I've spotted the hand of Marcel Breuer, who lived a couple of doors down the hall and developed some of the first cantilevered metal chairs here in Dessau, using techniques he learned at the local aeroplane factory. Sadly, the label on the base reveals otherwise: this is Rigg, made by Ikea.

So surely the bent steel chair is an original Breuer? "Actually, that's byMart Stam," corrects Thöner. "He invented them first." The Dutch architect's designs, spotted by Breuer's friend Mies van der Rohe, soon filtered through into the Bauhaus workshops, and it was not long before a patent lawsuit came to court – in which Stam emerged victorious. In the space of this 24 sq m bedroom, which feels incredibly generous compared to the 6.5 sq m most of today's students enjoy in the UK, the history of 20th-century design is compressed and blended into a primordial soup of originals and copies, and copied originals, an infinite feedback loop returning to the very place where it all began.

Standing on one of the concrete balconies, which project out from the bedrooms like a grid of little diving boards, it is hard not to feel a wave of nostalgia for the Bauhaus experiment. Could this be the very spot where Albers gazed down at the promising young weaving student, Anni Fleischmann, who lived on the "ladies' floor" below and would become his wife? Is this where textile designer Gunta Stölzl set up her easel and drew inspiration from the views of rolling fields (since replaced by beige blocks built in a folksy nationalist pastiche)?

Photos in the archive show quite what a lively social space this facade of stacked front gardens became, following Gropius's idea for the Bauhaus as a social condenser as much as anything else. The building's 28 rooms were reserved for both the Jungmeister (young masters) and "promising students" – in line with his tenet for the "cultivation of friendly association between masters and students outside the work context". The result was a cultish, close-knit community, which inevitably resulted in multiple staff-student couplings.

"In addition," he wrote in the school's manifesto, there were to be "theatre, lectures, poetry, fancy-dress parties, and a structure of light-hearted ritual at these social occasions". The accommodation block leads on to what was the canteen, which opens on to the stage of the auditorium, an arrangement that consciously blurred the boundaries between performance and life. It was the spectacular parties staged here, as Stölzl would later write, that became the barometer of the Bauhaus.

A Bauhaus room.

Wandering the echoing, empty halls of the place today, where tour groups shuffle to and fro around the Unesco world heritage site under the watchful eye of their guide, it's hard to imagine quite how outlandish it all was. Under the leadership of theatre workshop masterOskar Schlemmer, fancy-dress was taken very seriously indeed, often extending to week-long extravaganzas.

There was "the beard, noses and heart party" for which a dedicated costume advice centre was set up, dishing out homemade wigs and beards from a hairdresser's salon. There was White Festival, for which the invitations specified guests come "2/3 white, 1/3 coloured; stippled, diced and striped"; while the programme promised "the emotional, the epochal and the normative; weaving in the forest, p-p-poetry, uncle lala in the schoolyard and a criminal symphony".

Ever keen to integrate with the youngsters, Gropius often hired a dance teacher from Berlin to come and teach his staff the latest moves, holding intensive courses to master the ways of the Charleston – a level of organised fun that sent his neighbours Klee and Kandinsky into a rage.

It all came to a wild climax: the final party in 1929, a metal-themed riot, subtitled the "bells, jingling, tinkling party". Invitations suggested that gentlemen come as an egg-whisk, a pepper-mill or a can-opener, while ideas for the women included a diving bell, a bolt or wing-nut, or a radioactive substance. The building itself was transformed, with its windows covered in tinfoil, while visitors arrived by way of a swooping metal slide, above which dangled 100 glittering spheres of silver and glass.

Standing on the corner of the long axial avenues, now named Bauhausstrasse and Gropiusallee, with the building still gleaming from recent renovations, there is little sense of this fun and mischief. After the school closed in 1931, the complex was used for Nazi training, then damaged during the war. It served as a hospital and driving school before finally being restored in the 1970s. Now preserved in aspic, hosting exhibitions and the occasional group of postgraduate students, it sadly calls to mind what Oskar Schlemmer first noted when he arrived in Dessau in 1925: "Everything so bleak and dreary. No life."

With almost hostel-cheap prices, let's hope the rooms attract crowds of architecture and design students, to reinfect the pristine white shell with the spirited energy it needs. Just don't forget your egg whisk.

> via The Guardian