Submitted by WA Contents

BUZZFEED, BIKINIS, AND THE BIG RETHINK

United Kingdom Architecture News - Oct 09, 2013 - 23:20 4587 views

THE CASE FOR DE-DEMOCRATIZING THE ARCHITECTURAL PRESS

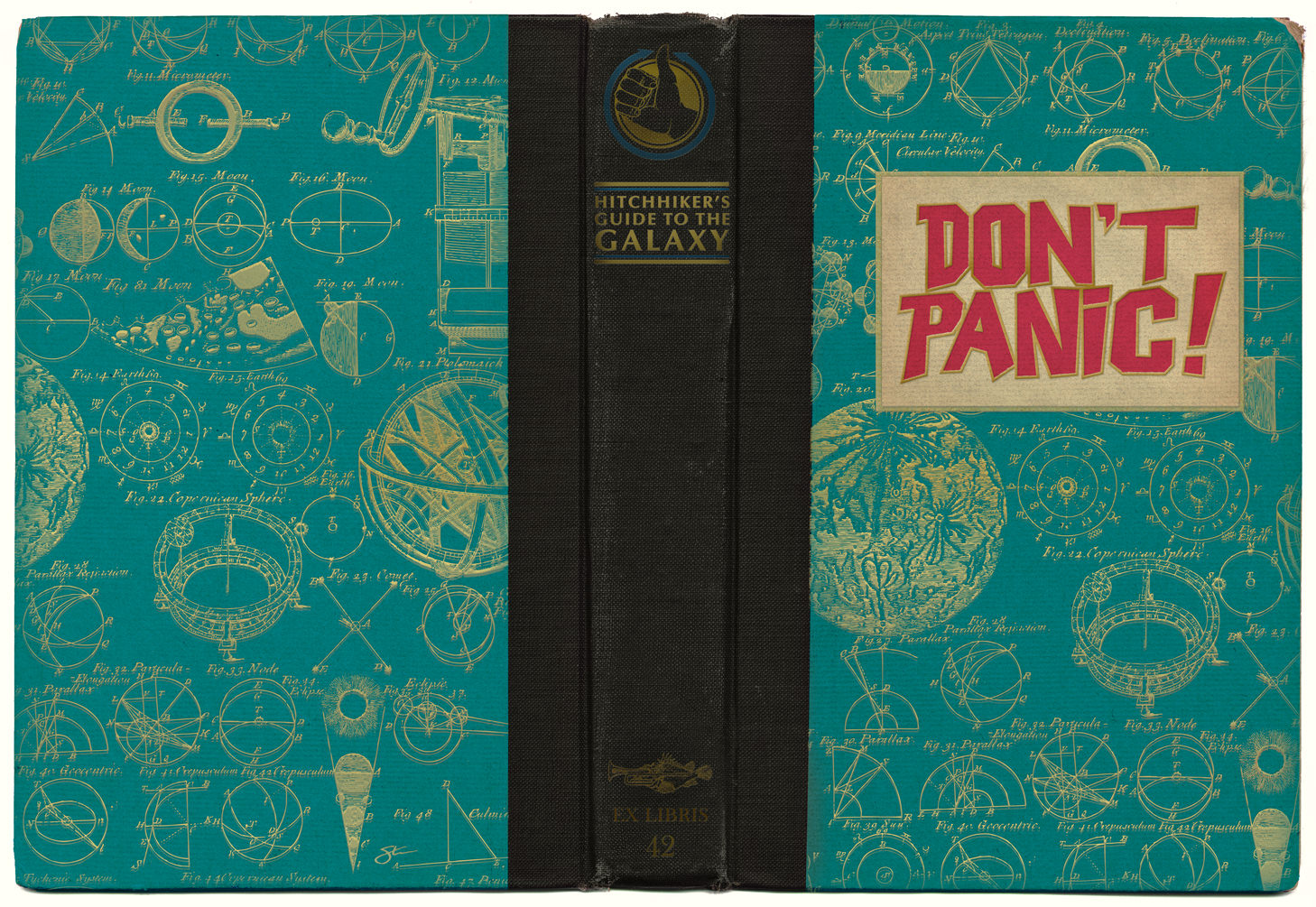

THE BOOK JACKET OF DOUGLAS ADAMS’ 1978 HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY GAVE PREEMPTIVE INSTRUCTIONS FOR TODAY'S ERA OF MEDIA OVERLOAD.

As an editorial coordinator at The Architectural Review, Phineas Harper is no stranger to the ins and outs of online publishing. Prompted by a June blog piece in uncube about architectural jargon in press releases, here Harper delves into the vortex of today’s frantic click-driven online architecture media, and argues that it might be time to put a stop to the so-called “democratization” of the press. This will take you ten whole minutes to read, and it’s worth it.

“Don’t Panic” reads the inscription famously emblazoned in large friendly letters on the back of Douglas Adams’ 1978 novel The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – stalwart advice to anyone in a difficult circumstance who must make critical decisions. Yet panic was nowhere to be seen when in 1995 Adams joked that trying to explain to publishers how the coming of the internet would affect their business models was rather like trying to explain to the Mississippi, the Congo and the Nile how the coming of the Atlantic Ocean would affect their currents. At that time, Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web (later to becomeYahoo!) had just catalogued the 10,000 registered websites then online.

Today, the number of registered websites has passed an eye-watering 650 million and the full weight of Adams’ prediction is being felt. Publishers, from The New York Times to Der Spiegel, are feeling the heat as audiences move online and subscription volumes plummet. The industry is resisting panic, but the strain is palpable. As a member of the editorial team atThe AR, I’m no stranger to this fact. Despite the overwhelmingly positive reception our 2011 editorial relaunch attracted and the privilege of an intelligent, discerning subscriber-base, it remains an uphill struggle to stay afloat through rocky economic waters.

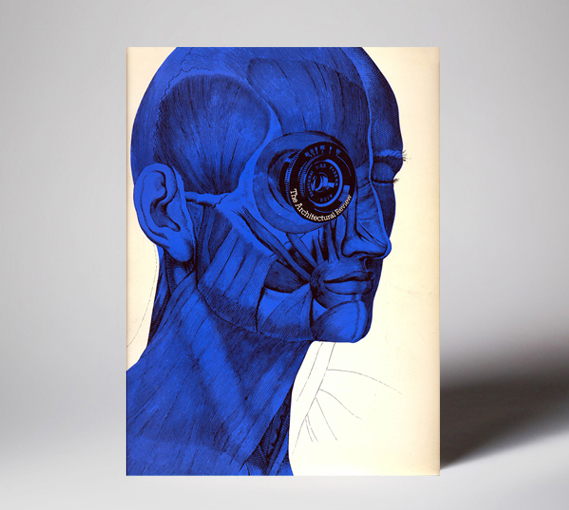

THE AR’S SPECIAL “MANPLAN” ISSUES BEGAN IN 1969, AMBITIOUSLY AIMING TO REDEFINE ARCHITECTURE AND PLANNING FOR THE 1970S.

Adams, however, was optimistic about the future potential of the internet. He anticipated a more open, efficient world where the oncoming information tide would unshackle the publisher from the limitations of fostering debate via the slow paper medium, ushering in a new epoch of liberated discourse. The internet would level the playing field, as established publishers would no longer be able to rely only on unrivaled contacts and distribution channels. Suddenly a society would be possible where the media landscape was controlled not by the intelligentsia of opinionated journalists but by a democratic marketplace. In a paper format, articles we find interesting are inevitably bound with those we find dull, yet we must still pay for both – the chaff subsidising the wheat. Online, readers would be in control, able to jump between stories that caught their eyes while ignoring whatever sounded too tedious or challenging, paying for only what they consume.

But in the cold light of day there is a sinister catch to this supposed democratization of media, one that publishers laughed off in the 1990s despite Adam’s warning, but that may yet erode the value of the publisher completely. The measure of an article’s worth has switched from its intellectual substance to how likely a browsing reader is to click on it. Yet popularity is a poor measure of worth. Writing might be popular but contain sloppy research, be inelegantly written, offensive in tone, derivative, formulaic or repetitive. We can see the shift in priorities played out on the websites of our newspapers and magazines. The right-hand news column of Pulitzer Prize-winning website The Huffington Post is driven by highlighting articles the average consumer is likely to click on. The lowest common denominators are not hard to guess; celebrity stories, peculiar YouTube clips and bikinis help deliver over 3.6 million users a month to the Post’s advertisers.

So what effect do these shifts have on architecture and architecture journalism in particular? Ours is a peculiar discipline that is at once practical, philosophical, artistic and political. It’s simply impossible to produce good architecture without serious consideration, so simplification and watered-down discourse becomes an urgent challenge.

Successful architecture publishers, like any other, are now in the business of constantly coaxing readers away from what they're reading in order to click on something more intriguing, funny or salacious. Dezeen’s website design is a masterpiece in curated visual distraction. The Architects' Journal’s most-read articles are not their thoughtful building studies but Buzzfeed-style top-tens. The sheer number of stories Archdaily publishes is astonishing but with such a vast output the site has little time for critique, turning instead to reworking press releases and biased descriptions from the architects.

In this climate architecture jargon can thrive as only the shallowest level of engagement is expected from the thoroughly patronised reader. In June, in her uncube article “International Architecture English” Elvia Wilk examined the trend of increasingly nonsensical press releases emerging from PR companies, anxious to cement their client’s intellectual credibility, appealing to rushed publishers keen to increase their web traffic. The result is a vicious circle of gibberish that weakens our critical capacity as a profession and alienates the wider public from our discourse.

Paradoxically, there are perhaps more compelling architecture critics in the world than ever before. The explosion of blogs, self-publishing and podcasts has invigorated a fierce interest in architectural writing and cultivated a generation of amateur and semi-professional writers. Never has it been easier to disseminate our thoughts – and yet this very aspect of globalized communications means we have become over-saturated, unable to collectively consider big issues outside of a few stage-managed political narratives. Some argue that Twitter and similar digital platforms allow crowds to kick-start collective debates through trends, yet with so many voices clamoring to be heard, only the simplest of messages can sustain a broad following.

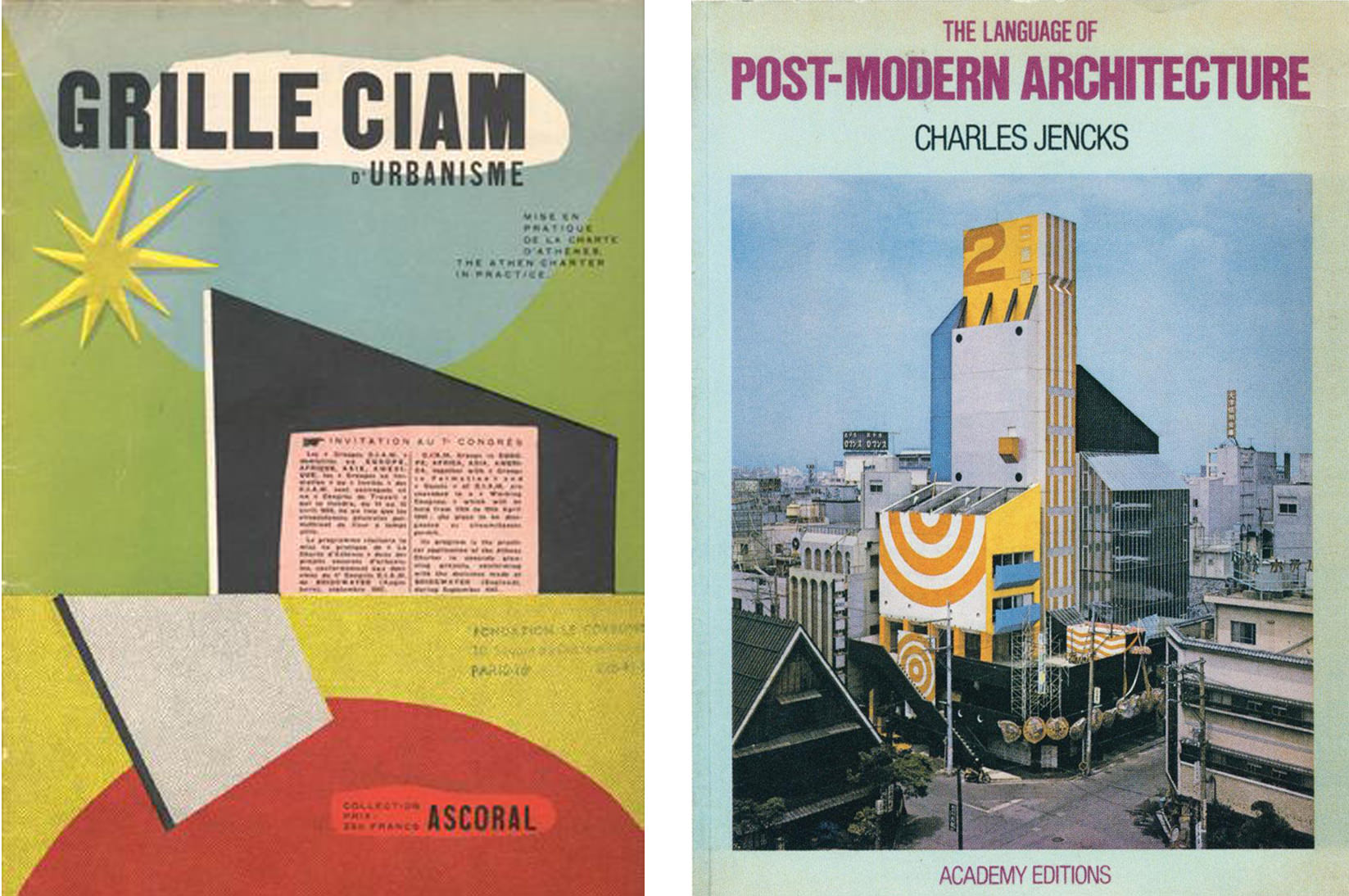

In 1715 Colen Campbell published the first volume of Vitruvius Britannicus, and in doing so started a debate that swiftly evolved into the Georgian era producing some of the most loved British architecture of all time. Le Corbusier and CIAM’s 1935 Athens Charter initiated a comparable sea-change in planning, which dramatically altered the post-war urban landscape of Europe. In 1977, Charles Jencks’ The Language of Post-Modern Architecture articulated a vision of an architecture responding to context, body and psychology that underpins the architectures of megastars such as of Gehry and Koolhaas as well as small-scale practices worldwide. Today, without the capacity of a publishing house to push radical ideas, and without the capacity of the public to consider those ideas collectively, such a seismic shift in thinking seems impossible.

THE ATHENS CHARTER BY CIAM AND LE CORBUSIER (1935) AND THE LANGUAGE OF POST-MODERN ARCHITECTURE BY CHARLES JENCKS (1997): TWO PRE-INTERNET POLEMICS THAT ALTERED ARCHITECTURAL DISCOURSE FOREVER.

Peter Buchanan’s The Big Rethink, published as a series of essays in The AR, may be one of the most important – and damning – critiques of architectural production and modernity written for some time. It is comprehensive, eloquent and propositional, offering a coherent intellectual framework for architects in an age of environmental and economic crisis. For subscribers each essay is an intrepid highlight, but for others it is merely another complex idea they’ll never have time to put their minds to.

To test my hypothesis I wrote the light-hearted 11 Things to Know Before Starting Architecture School – fun advice, but of little architectural value compared to the canon of superb features on the AR website. But sure enough, within two weeks of publication my little story had climbed to be our most-read online article of all time – an impressive, if terrifying result for something bashed out in less than an hour.

Douglas Adams’ vision of a democratic media is upon on us. The reader has been passed unprecedented power to set the agenda of the publisher. But power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Is it time to panic yet?

- Phineas Harper is Editorial Co-ordinator of The Architectural Review. He studied architecture at the The Welsh School of Architecture and lives in a narrowboat on the River Thames.

> via UncubeMagazine