Submitted by Berrin Chatzi Chousein

The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces

Turkey Architecture News - Aug 31, 2013 - 20:33 8203 views

“The way people use a place mirrors expectations.”

“Just bring your own contents, and you create a sparkle of the highest power,” Anaïs Nin wrote about the poetics of New York in 1939. But what, exactly, are those contents, and how does a city keep its sparkle?

In 1970, legendary urbanist and professional people-watcher William “Holly” Whyte formed a small, revolutionary research group called The Street Life project and began investigating the curious dynamics of urban spaces. At the time, such anthropological observation had been applied to the study of indigenous cultures in far-off exotic locales, but not to our most immediate, most immersive environment: the city, which hides extraordinary miracles of ordinary life, if only we know how to look for them. So Whyte and his team began by looking at New York City’s parks, plazas, and various informal recreational areas like city blocks — a total of 16 plazas, 3 small parks, and “a number of odds and ends” — trying to figure out why some city spaces work for people while others don’t, and what the practical implications might be about living better, more joyful lives in our urban environment. Their findings were eventually collected in The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (public library) in 1980 and synthesized in a 55-minute companion film, which you can watch below for some remarkably counterintuitive insights on the living fabric of the city.

Far more intriguing than the static characteristics of the architectural landscape, however, are the dynamic human interactions that inhabit them, and the often surprising ways in which they unfold. Whyte writes in the preface:

''What has fascinated us most is the behavior of ordinary people on city streets — their rituals in street encounters, for example, the regularity of chance meetings, the tendency to reciprocal gestures in street conferences, the rhythms of the three-phase goodbye.''

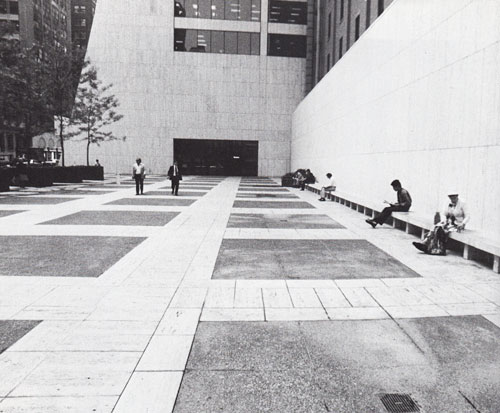

Whyte’s team went on to investigate everything from the ideal percentage of sitting space on a plaza (between 6% and 10% of the total open space, or one linear foot of sitting space for every thirty square feet of plaza) to the intricate interplay of sun, wind, trees, and water (it’s advantageous to “hoard” the sun and amplify its light in some cases, and to obscure it in others). These factors and many more go into what makes a perfect plaza:

''A good plaza starts at the street corner. If it’s a busy corner, it has a brisk social life of its own. People will not just be waiting there for the light to change. Some will be fixed in conversation; others in some phase of a prolonged goodbye. If there’s a vendor at the corner, people will cluster around him, and there will be considerable two-way traffic back and forth between plaza and corner.

[…]

The area where the street and plaza or open space meet is key to success or failure. Ideally, the transition should be such that it’s hard to tell where one ends and the other begins. New York’s Paley Park is one of the best examples. The sidewalk in front is an integral part of the park. An arborlike foliage of trees extends over the sidewalk. There are urns of flowers and the curb and, on either side of the steps, curved sitting ledges. In this foyer you can usually find somebody waiting for someone else — it is a convenient rendezvous point — people sitting on the ledges, and, in the middle of the entrance, several people in conversation.

Urban parks, Whyte discovered, were an integral mechanism for stimulating our interaction with the city — perhaps one reason they are so enduringly beloved:

''The park stimulates impulse use. Many people will do a double take as they pass by, pause, move a few steps, then, with a slight acceleration, go on up the steps. Children do it more vigorously, the very young ones usually pointing at the park and tugging at their mothers to go in, many of the older ones breaking into a run just as they approach the steps, then skipping a step or two.

And so we get to the surprisingly intricate science of yet another seemingly mundane element of the urban experience: steps.

''Watch these flows and you will appreciate how very important steps can be. The steps at Paley are so low and easy that one is almost pulled to them. They add a nice ambiguity to your movement. You can stand and watch, move up a foot, another, and, then, without having made a conscious decision, find yourself in the park.

Other factors that spur a lively and robust social interaction include public art and performance:

''Sculpture can have strong social effects. Before and after studies of the Chase Manhattan plaza showed that the installation of Dubuffet’s “Four Trees” has had a beneficent impact on pedestrian activity. People are drawn to the sculpture, and drawn through it: they stand under it, beside it; they touch it; they talk about it. At the Federal Plaza in Chicago, Alexander Calder’s huge stabile has had similar effects.

Then there’s music, known to enchant the brain and influence our emotions in profound ways:

''Musicians and entertainers draw people together [but] it is not the excellence of the act that is important. It is the fact that it is there that bonds people, and sometimes a really bad act will work even better than a good one.

In another chapter, Whyte considers the problem of urban “undesirables” — drunks, drug dealers, and other uncomfortable reminders of how our own lives might turn out “but for the grace of events.” Here, too, Whyte’s findings debunk conventional wisdom with an invaluable, counterintuitive insight: rather than fencing places off and flooding them with surveillance cameras (which he finds are of little use in outdoor spaces — something that would delight artist and provocateur Ai Weiwei), we should aim to make them as welcoming as possible

''The best way to handle the problem of undesirables is to make a place attractive to everyone else. … The way people use a place mirrors expectations.

This, in fact, reflects the most fundamental and timeless insight of the entire project, echoing the famous Penguin Books maxim that “good design is no more expensive than bad”:

''It is far easier, simpler to create spaces that work for people than those that do not — and a tremendous difference it can make to the life of a city.

Slim but fantastically insightful, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces is a foundational piece of today’s thinking on what makes a great city and a fine addition to these essential reads on urbanism.

Watch the fascinating companion film, digitized in its entirety, below:

> via brainpickings.org