Submitted by Tarun Bhasin

Recapitulating Z-Axis 2015 #2: Lessons from a Pritzker laureate

India Architecture News - Dec 03, 2018 - 12:07 13396 views

Lessons from a Pritzker laureate

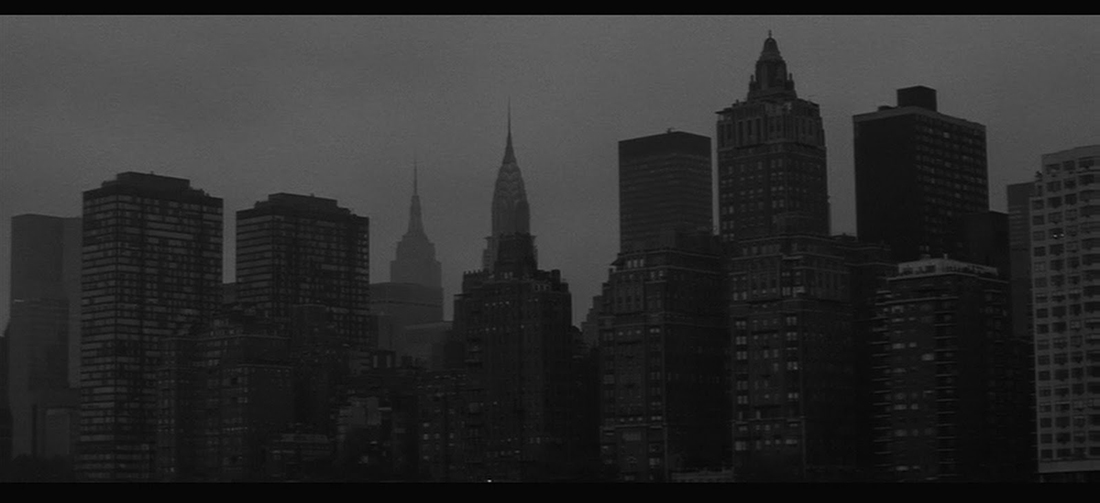

The frame fades-in to reveal a shot of a ghetto of skyscrapers, there is no point of reference to the ground and there cannot be. You can see the Chrysler building rising from behind a few concrete mid-rises following which your eyes dart to the Empire State Building situated further back, appearing almost like a silhouette. The image is black and white, sooty, and imitative of the pollution-ridden skies of the city that abolishes almost every detail. It is only after three seconds into the shot that the background score plays - it is Jazz! There is nothing more left to the imagination. The movie is set in Manhattan, if only you knew the name of the movie, I am talking about the 1979 American feature by Woody Allen titled on the city itself.

While Technicolor features were prescient in Hollywood at the time, the director found it appropriate to present the entire movie in black, perhaps, because they say that Manhattan is a city that was ‘perceived in black and white’ and the director found it to be the best way to represent the city. The shots following the opening reveal more images of the Manhattan skyline, its waterways, street life and works, buildings clad either in stone or black glass, the famous Broadway, and Central Park. These are certain images that can evoke the spirit of Manhattan in anyone’s mind. More than the events, these tangible representations form strong memories and opinions about the city that are singular in nature, timeless and definitive of establishing ‘context’. This is where the background score supplements the imagery by presenting a genre that is again closely associated with the ‘context’ of Manhattan. And when the narration by Woody Allen appears as follows – ‘Chapter 1: He adored the New York City…’ - he does nothing more but consolidates the identity of the character in reference to the images on the screen and to the music playing in the backdrop.

This recognizable and comforting architectural imagery and character are common in all of his movies, from Manhattan, Annie Hall, and Hannah and her Sisters, to Match Point, Midnight in Paris, and To Rome with Love. The movies are breathable. Whether it is in the opening or closing scenes, or lengthy debates carried through long shots taken on a boulevard in clear perspective, or awkward conversations on the corner of a street; Woody Allen’s characters are defined by their city of existence. Either they are in awe of their surroundings or intimidated by them, but they almost certainly have a relationship that gives us an insight into their personalities and adds a layer of depth to their stories. Underlying this observation are three common themes: the effect of architecture of a city on its collective memory (the BnW shots of Manhattan), the relation of architecture of the city to its culture and socio-politics (Jazz), and the role of architecture of the city in defining the character of its inhabitants (what does it really mean for one to say ‘He adored the New York City…’).

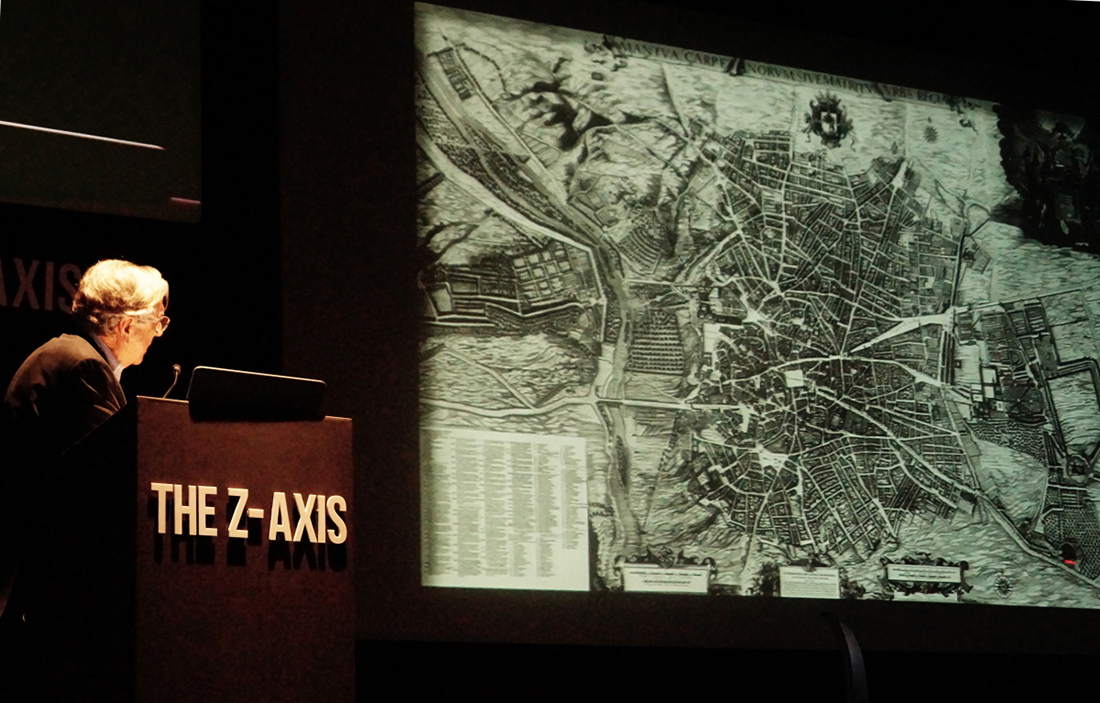

On recognizing these particular themes, it becomes evident that architects have the responsibility of defining public memories, of leveraging human expression, and of influencing individual perception. Be it the London of Sir Christopher Wren, Berlin of Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Vienna of Otto Koloman Wagner, Barcelona of Antoni Gaudi, or Madrid of Juan de Villanueva, architects have always played an important role in the growth of their respective cities. What they designed and left behind is substantial in generating life and definition of character in these cities. This is why the respective cities are recognized through images of their works – works that are key to understanding the place in question. And on this note, Pritzker Prize laureate Rafael Moneo began his lecture by deciphering texts from Aldo Rossi’s ‘The Architecture of the City’ to tell us about how cities reflect sanctity through architecture, and added a slight nuance of his own to this notion, by proposing the kind of role architects have to play in the making of cities. ‘The life of architects is something deeply rooted in the city, and their work is associated with cities, influenced by the places in which they live and work…’ much like the characters in Woody Allen’s movies.

While the tensions expressed in the beginning, related to Correa, the conference and Goa served as a precursor to the event; it was in the lecture delivered by Moneo (his first ever in India), where he explained his own works on La Castellana Boulevard in Madrid, that these tensions which were seemingly individual till then, suddenly began to coincide and a pattern of reference began to emerge. With these themes churning in the back of everyone’s mind, as he read more and more from Aldo Rossi’s work, it became apparent that he was going to talk about an architect’s reaction in the days of globalisation, and to the idea of a ‘generic city’.

Image: Rafael Moneo explaining the history through a plan of Madrid, courtesy of Charles Correa Foundation, Panjim, 2015

Naturally, globalisation as a phenomenon has created a combinatorial explosion attributing all distinctive characters to each city. When we mix every possible colour together, we only get grey in return. This perpetual greyness of cities brings architects to think that it isn’t so easy to configure designs according to today’s cities, because even if they did try, which colour would the design correspond to? It is a problem of scale, as in the metropolis the work of an individual dissolves in the ocean of what is built. To counter this problem several architects can work in favour of one identity of the city, probably, but that too is confrontational. Because when we zoom out and begin to understand the possibility of the scale of this collaboration, we begin to understand the whole world as one big city.

It is necessary to emphasize at this moment that globalisation has led us to realize that the city is gone in a way, the city is the whole world now, as we are not able to identify cities in the way we used to before. This is where Moneo presented his own works to show how architecture still has a chance to identify with the city, by tabling a very serious question in front of the audience – ‘Should we think we knew that the city would disappear giving rise to a generic city regardless of size or scale? And, should we simply accept that attributes such as identity and character, which we used to speak of the city, would not be applicable now that the architects rarely work consistently in a particular city?’

This was the first of many unsettling and difficult questions that he left the audience to reflect upon. Like a floodgate of moral and ethical dilemmas associated with problems of present architectural practices, it had a very genuine implication as its premise – architects, today; do not seem committed to the city they work in! If we are to consider the contrary, then perhaps, we need to answer if the current state of practice permits us to name each city and distinguish them on the basis of their distinctive qualities. If we are to say that it does permit architects to operate beyond the expectations and obligations to client and professional conduct, then we need to decide whether, as a discipline, we must ask individuals to identify the peculiarities of a city and incorporate them equally in their explorations of visceral meanings of space, and only then label their inventions as ‘accomplishments’.

In the days of globalisation, how much shall the current practice be in dialogue with what has preceded us? Should the architects be bound to the character of the city and dialogues on context as much as they are connected to social problems of urbanisation and rationalisation of living? Should each architect design their own tools of operation, and with experience, translate them to different cities to debase the spirit of each place, and should in this case, the institutions that leverage commissions to foreign architects, in hopes of receiving work of quality, and of dreams, must shed away the idea of retaining their own history and sense of belongingness?

In a sweeping sentence, we had his answer; ‘Nothing in my view is more favourable than practicing in one’s own city where the common ground will frame our daily lives.’

This statement that can be closing of an argument was the opening of the comprehensive presentation on four architectural works on La Castellana Boulevard in Madrid; these were in the order of rendition – The Bankinter Headquarters, The Bank of Spain Extension, Museo del Prado Extension, and the Madrid Atocha railway station. But, before the architecture came to place the city came to existence, or at least the idea of the city did. Moneo took the audience through a profound re-enactment of the story that is present-day Madrid, talking about the circumstances behind its conception, the logic behind its layout; and sitting there I understood how architecture could be used as a tool for the ritualistic revival of myths of the city, and how an architect could take center-stage as the conductor of the entire arena. I wish to call these stories and logic as myths, not because I am stating them as fictitious, but to state them as information that is more powerful than the truth of circumstances of those times. To say, what Moneo was talking about the identity of La Castellana Boulevard couldn’t have been the only interpretation or history behind its existence; nonetheless, it was how the boulevard came to be perceived over time and therefore, this perceptual definition superseded any other annotation. This mythical identity of cities must be respected, preserved, extended and added upon, and that is what he was trying to show through his projects.

Image: Bankinter Headquarter Axonometric, Courtesy of Rafael Moneo archives

For example, the Bankinter Headquarters’ success is rooted in three particular interventions. It is important to know that the project came up at a time when major commercial and financial institutions were trying to consolidate their position on the ‘superblock’ that extended from Plaza Colon to AZCA – the result of ‘Ley Castellana’, a law that was enacted for two decades to invite companies to participate in the development of the block with a lieu of 90% tax redemption. At a time, when the block was characterized by villas representing the aristocratic architecture of by-gone eras, most companies resorted to tearing such structures down and coming up with spaces that were in tension with their surroundings and evoked a sense of futurism and reverence towards technology. Bankinter desired to assert its authority over than architecture of the block by being discreet and elegant; and Moneo forwarded the thinking by retaining the existing villa on site and utilizing its spaces in the new office building, thus, leveraging the by-laws existing at the time. Hence, the preservation of history was the first intervention that set the project apart from its contemporaries.

The second intervention was dialogue. The new office block was conceived on the edge overlooking the villa with its back facing to housing quarters that marked its immediate context. To generate a visual narrative between the old and the new, the block came up as a wall facing the villa, with neat repetition of windows characteristic of Aldo Rossi’s Modena Cemetery. The effect of the wall was further accentuated by a sharp diagonal cut through the volume of the building to open up the visual space between the street and the housing quarters behind the wall. In a way, it not only retained the visual integrity between the housing quarter and the street, but the tapering volume also added to the suddenness and weight of the new block thereby establishing its place and identity. The third intervention not only served the needs of architecture that was outside the scope of design programme given to Moneo, but it established the design as a medium of visual communication between different elements in its context, thereby consolidating the identity of the institution, which has remained strong ever since.

Image: Bank of Spain, Madrid, Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The point that raises his interventions is tainted and impregnated by imagining cities through the lens of architects that precede him. He rests his designs on the hypothesis that the song of the city, its continuance, and identity belong to the works of an architect. The same design interpretation can be seen in the Bank of Spain extension where the architect refrained from polemic thinking once again. He realised the diverse architectural vocabulary of the existing blocks owing to multiple extensions conceived by different architects over the years, culminating to an empty corner on which the new block was supposed to be placed. Thus, perceiving the corner as something that tied the entire block together, the extension was created to imitate the existing growth pattern. Even though the project lay dormant for 25 years, Rafael Moneo did not deter from his approach, but in his own words, the stability of the city in the given period allowed him to detail this approach, where the spaces inside would cater to the modern requirements, not as a new piece, but as part of a larger compositional environment resulting from sewing and connecting diverse pieces and attributes of the old blocks.

Image: The historic Amigos Museo del Prado, visible through the interior central space of Museo del Prado Extension, designed by Rafael Moneo, Courtesy of Rafael Moneo Archives

Today, time doesn’t favour such interventions. It isn’t slow anymore. It doesn’t allow cities to be built on values and rituals, it does not allow the sense of judgment we have used till now. The Vitruvian triad – Firmitas, Utilitas, and Venustas – is broken now according to Moneo. In his opinion, the present architectural rational is based on market price and economic interest, a language created by developers to advance their cause. Since, rationality in construction isn’t needed as much as it was once to be able to build what is possible now, due to advancement in building materials and construction technology; capitalism leverages this freedom to commoditize spaces. His design Museo del Prado extension, retains the present-day rationale of a building as commoditized space, as an object when viewed from the scale of the city, but he does his best to dilute its edges in the immediate context to conceive spaces without a border. The axial shift in the new museum block creates an absurd juxtaposition when approached from Calle Ruis de Alarcon, due to the narrowing down of the street section. But by doing so, the building places a greater emphasis on the ornamental public plaza created in front by treating the contours, allows pause and therefore, appears inviting and warm. The axial tilt allows the façade of the building to directly face the historic structure of Amigos Museo del Prado, with the central interior space directly looking into the landmark building. Thus, in a way, the experience of the galleries of the museum block is defined by the existence of the historic building in its environment, which in itself generates an additional narrative that superimposes the existing narrative of context, to create a new ritual through its design. This clear distinction between the inside and the outside and the forced connection of the new museum block to the old one helps in retaining the existing built memory of the context while supplementing the requirement of the new design program.

"And I end up changing the context but indeed tie in my work to be understandable in what the context has meant in the structure of the city, and I would like that the city prevails on what I did. An architect is dancing to the sounds of issues that have been imposed through competition and client, but the idea of place must remain important throughout the process – to remain sensitive to the city."

Image: The concourse of Madrid Atocha Railway Station, courtesy of Rafael Moneo Archives

What I just explained in a few hundred words, are works that stem from almost three decades of practice and efforts given to understanding one particular city and its values. Paraphrasing the question that we began with at the beginning of the essay, it is evident that history played a very important role in the participation of both the architects discussed till now. But today, in times, when the engagements of young architects are not limited to a particular city, especially for a diverse geography such as India, how much must one consider the understanding of the history of any city to be an important factor in engagement with such contexts?

"When you work wherever that is not your place of residence, as it is going to happen more and more in future, where it is difficult to believe that architects, as it happened in the past, will be related and connected and attached to a city; it is important to remember that cities have something different of each other. It is important to be connected to them, [belong to them] and try to understand their plot because the city does not need your own expression but needs to serve the reality – the reality of the city."

Talking about the generic city, a city that has grown out of scale by enveloping suburban areas and ingenious places that once marked its periphery; how, if one must, help the terrible city co-exist with these places and fulfill the pressure and element of continuity?

"I am not sure about what I do, I find in cities this pressure – I understood what they could be. It is difficult to recognize the work of an architect in a city these days because they are of another scale. If I must, let me say, I would be ready to split cities into many other cities just to adjust the contemporary approach given to cities."

So do architectural interventions really hold meaning only in their immediate context?

‘No, they are relevant even outside the periphery of values that exist in central parts of the city. The idea from my works is still valid to megacities, where an architect might find a lack of substantial architectural elements to begin with. One must remember that a wall applied with a mechanism and approach while working in one neighbourhood might be imprecise for another.’

Image: Structure of Madrid Atocha Railway Station's concourse, courtesy of Pritzker Prize

I think the above answers are best sufficed through his last project on the list – Madrid Atocha railway station. Railway stations are a gateway into a city; they represent its link to the nation at large as they help maintain its economy. They provide a sense of departure and arrival, demarcate territory, communal identity, and particularly for any urban agglomeration, provide a sense of encounter to delineate its public memory. Unlike libraries or museums that display information in structured narratives to disseminate history and culture, a railway station relies on space-time immersion into the urban fabric and retains subjectivity by remaining an experiential place. It remains sublime and disseminates the aspirations of the society allowing them to mingle with the real-time feelings of the traveler. Within this typological derivative, we can find Moneo’s responsive to the aforementioned questions.

Madrid Atocha Railway Station lies outside the periphery of the historic complex, at the end of the boulevard. Its expansion was conceived to accommodate the new high-speed AVE trains, which were seen as a huge demarcation of progress. The building was supposed to create a larger network of transport along with buses and subways, and also define itself as a landmark in an area that marked the beginning of city blocks distinguished as ‘unhappening’ when compared to the developments of the time that were coming up in the city center. But the project being the entry point for a person aspiring to settle in Madrid held a value that moved the idea of its space beyond its history. By realizing this nuance, the architect crafted a building distinguished by a circular lantern-esque entrance hall, pillared concourses, high ceiling, and flat roof. The massive volume, modern and industrial in nature, remains open to the subjective feelings and expectations of the vast conundrum of people while echoing their aspirations as a collective cause. Although the addition of necessary infrastructure, green spaces, imagery, and symbolism in surrounding spaces generate the essence of the context of Madrid, it is the concourse that matters still. It is a space that moved beyond the idea of context to voice the identity of the individual and aspirations of development in a city, to transform and generate spontaneity in blocks situated on the urban periphery, at a time when they suffered from lack of identity. One must realize how slippery it is to talk about an ambiguous term such as identity. The design of Madrid Atocha railway station showcases that the name of a city is not just a style but something more than that – something that efficiently defines the modern public memory of Madrid, leverages an expression to new places of development, and influences individual perception of people entering the city with hopes for a better future – thereby becoming remarkable of fulfilling the themes prescient in the beginning of the lecture and proving conclusive to its premise.

Retrospectively, architecture, in the language of the respective architect, does not contradict but is always free to assume conflict, only to change what is perceived by him as wrong, and go beyond the context. It establishes a sense of continuity, to keep and maintain alive – the ‘context’ – where his buildings are trying to increase the life of buildings in their surroundings. It is distinguished by spaces that grow and move in time to work in the city, through the memories of its people. The buildings assist and not reject, and have in themselves the hint to work without betraying how cities allow being named. It is a work that moves beyond the idea of a generic city, and even beyond the image of what the city used to be in history. Through the lecture, Rafael Moneo established a precedent for all architects to find value in their city, to place it above their own desires and to recognize their designs and themselves, within the existing myths of their cities – a remarkable reward for an architect according to him – and a difficult precedent to follow for the speakers appearing on day two and three.

Image: Madrid Atocha Railway Station by Rafael Moneo, courtesy of Pritzker Prize

*'Recapitulating Z-Axis 2015' is a six-part essay series made in collaboration with Charles Correa Foundation, to provide a first-hand narrative of the proceedings of the first edition of Z-Axis Conference held in 2015 at Kala Academy, Panjim, Goa, India.

Top Image: Opening shot of 'Manhattan' by Woody Allen, courtesy of United Artists