Submitted by Hanieh Lotfipour

An Interview with Amir Bani-Masoud about his newly published book, Contemporary Architecture in Iran

Iran Architecture News - Jul 24, 2020 - 16:34 16456 views

In this particular interview, we talk about the book named "Contemporary Architecture in Iran" written by Amir Bani-Masoud which is published in 2020.

Hanieh Lotfipour: Dear Mr. Bani-Masoud. I deeply appreciate your time and cooperation. Would you mind telling us a little bit about your background?

Amir Bani-Masoud: Thanks a lot for your invitation. To be concise, I was born in Iran, living in Canada. I am a specialist in Iranian contemporary architecture. Studying architecture at IAUT and then McGill University, I was a faculty member at IAUT (1997-2018). I have lectured and served as a visiting professor at several universities. I am also the author of seven books, with three in press.

Hanieh Lotfipour: So interesting, we know that one of your books has been recently published, so may I kindly ask you to tell us about it?

Amir Bani-Masoud: Contemporary Architecture in Iran aims to provide an enjoyable history of contemporary architecture in Iran from Iran’s modernization during the mid-1920s to the present. It explores how hopes for a new and better society in Iran became linked to new architectural forms. The book discusses how factors such as the development of a new environment, the rise of the architectural profession, and the transformation of the building industry in Iran, all led to the emergence of mature modernist architecture in this country.

This book is divided into seven chapters. The first chapter consists of two major parts. The first part explores factors that led to the first blossoming of modernism in Iran and why Tehran was the locus of this innovation. The second part focuses on the urban renewal program, the growth of the modern industry, and the oil urbanization in the reign of Reza Shah which all led to massive urbanization and the rise of new cities. Focusing on three architectural tendencies (Neoclassicism, Islamic revivalism, and the neo-Achaemenid style) of the Iranian national style, the second chapter examines how nationalism as a political approach led to the development of a new style in Iranian architecture. The third chapter examines the modernization of Iranian architecture, which entailed the introduction of new forms and techniques. The fourth chapter focuses on the relationship between the modern house, which was a key aspect of Iran’s modernist fabric, and Iranian academic architecture. The last part of the fourth chapter examines the mid-1940s apartment houses that catered to tenants of various incomes. Focusing on housing in the Metropolis, the fifth chapter discusses the first multi-block high-rise housing complex projects that arose during the 1970s. This chapter also discusses the White Revolution which not only attempted and achieved a far-reaching transformation of Iranian society but also accelerated the growth of the professional middle class. The White Revolution, which developed into a series of white elephant projects, was the main reason for the rapid urban growth rate in Iran. The sixth chapter considers the three phenomena of the International Style, High Modernism, and Modern Regionalism, and thereby provides a glimpse of the state of Iranian Architecture. The last chapter of this book covers Iranian architecture after the 1979 revolution. It explores why at this time the main concern of Iranian architects was to marry tradition with the ideas and developments of modernist architecture. This chapter also discusses the new, young generation of Iranian architects that have a global and international rather than regional and imperial focus.

Tehran Railway Station, Tehran, 1937

Tehran Railway Station, Tehran, 1937

Hanieh Lotfipour: So, when and how did architecture begin to be professionalized in Iran?

Amir Bani-Masoud: Architecture began to be professionalized in Iran in the 1940s. During this time, Iranian architecture started to develop nearly all the features of a full-fledged profession. The first architecture school opened at Tehran University and an architectural association, the Iranian Society of Graduate Architects, was formed in 1945. Moreover, the first building codes and standards were established in the Municipality of Tehran. A new generation of Iranian modernist architects worked to create a bridge between the old world and the new. Many projects, including the design of large civic and public buildings, by this younger generation demonstrated a shift in aesthetics. These architects first attracted public attention at the start of the 1940s when they banded together to form a professional association, establishing a tariff, setting by-laws, and electing an executive board. Before this, Iranian architects did not have any sense of identity as a group and the public knew little about them or what they did. The association’s officers included leading members of the architectural profession. There were thirty-eight young architects in this association; all had professional training as architects. They not only wanted to raise architectural standards but also wanted the government to establish architecture as a profession with status and rights. They maintained that the right to practice architecture in Iran should be given only to those who either passed examinations that tested their architectural knowledge or demonstrated evidence of formal professional training. They also believed that the practice of architecture should be controlled through a professional society that offered the rights of registration and examination. Due in large part to the Iranian Society of Graduate Architects, architecture became a topic of extensive and lively discussion in Iran.

Karl Frisch. Municipality of Tabriz, 1943

Hanieh Lotfipour: extremely outstanding. I am very eager to read this book now. I believe it will be more interesting if you tell us what inspired you to start writing?

Amir Bani-Masoud: For me, what got me interested in taking up writing was a lack of books on Iranian contemporary architecture in English. My book is the first and only book regarding modern Iranian architecture which has been written in English, although there are several architecture books on different topics in Persian.

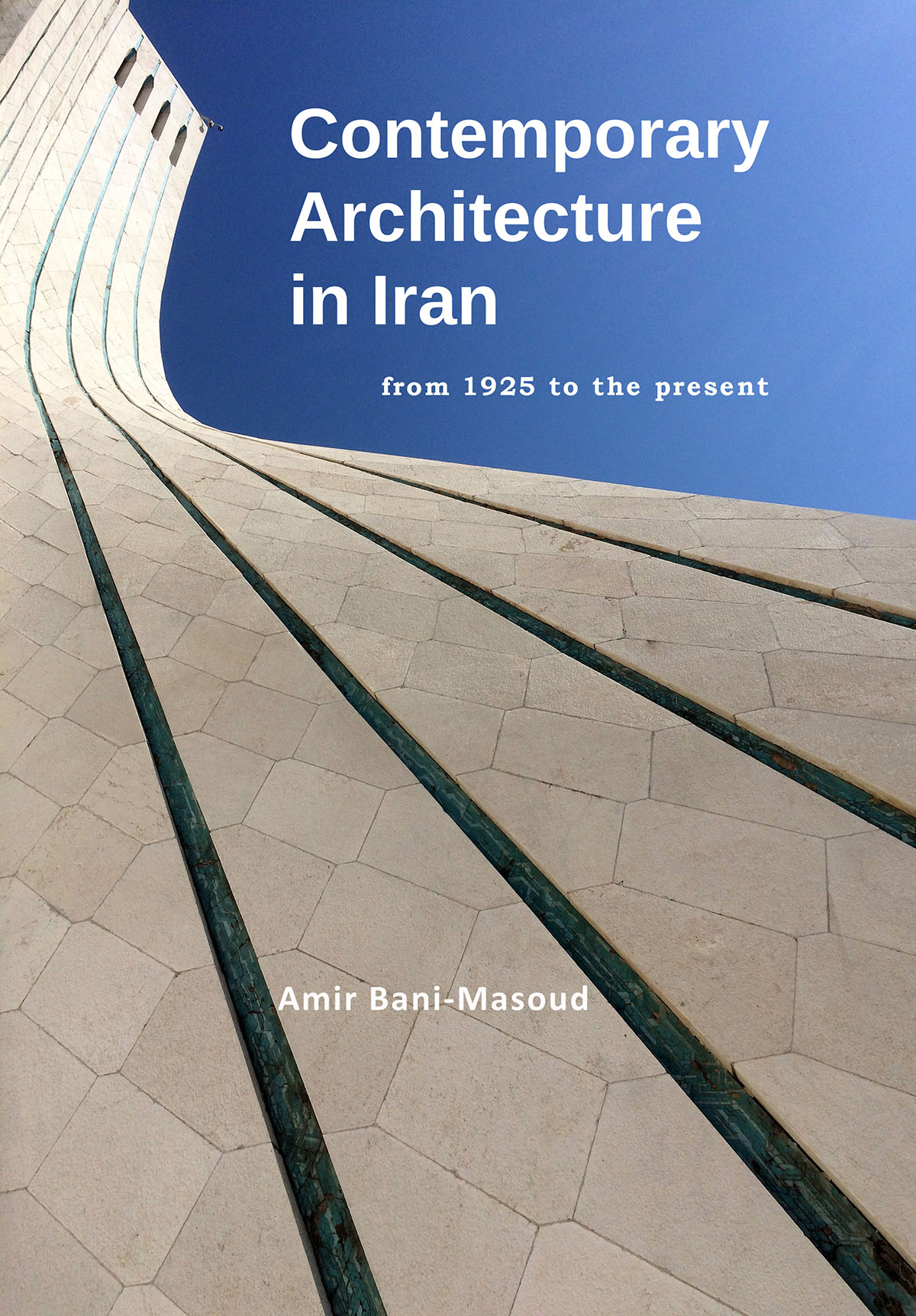

Hanieh Lotfipour: The cover photo is so eye-catching, would you mind telling us about the cover photo?

Amir Bani-Masoud: The book cover photo shows the Shahyad Aryamehr Monument (later renamed Azadi Square) which was designed in 1966 for the 2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire. Drawing on the collective memory of ancient and Islamic forms, the monument celebrated Persian civilization and culture. That is why we tended to prefer it for the cover.

Nikolai Markov. Municipality of Tehran, 1923

K. Zafar Bakhtiyar, A. Sadeq, and M Forughi. Reza Shah’s mausoleum, Rey, 1949-51

Hanieh Lotfipour: It seems difficult to reach these all information and documents, so how do you do research for your new book?

Amir Bani-Masoud: Sources of my book came from many different ways. First of all, this book is the result of my one and a half decades-long process of researching and writing about contemporary architecture in Iran. In 2009, I published my previous book entitled ‘Iranian Contemporary Architecture: An Inquiry into Tradition and Modernity’ in Iran. At the time, I interviewed some Iranian architects who generously shared their knowledge, insight, and reminiscences with me. Also, many wonderful office workers at various architectural firms provided me with essential information. However, my latest book has been written and published in Canada. Therefore, studying/living abroad and being an architect with my passion for writing gave me opportunities to access related resources including architectural magazines, books, and government documents that I have never had before for helping me to write this book.

Eugene Aftandilian and Roland Marcel Dubrulle. Ferdowsi School, Tehran, 1936-8

Heydar Ghiai. Royal Tehran Hilton, Tehran, 1960-2

Hanieh Lotfipour: In your opinion, who is the target audience for this book?

Amir Bani-Masoud: In my opinion, the book has a broad audience. It will be intended to enable Western readers to develop an understanding of modern Iranian architecture. It will also be of great interest to architects, urban planners, and historians both within and beyond Iran who want to know about Iranian contemporary architecture.

Rouholah Nickkhessal and Iraj Parvin. Rastakhiz Party building (now the Ministry of Interior Building), Tehran, 1971-78.

Hanieh Lotfipour: So far, Where can readers purchase your new book?

Amir Bani-Masoud: It is available on the Amazon website. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08B7LNDCQ

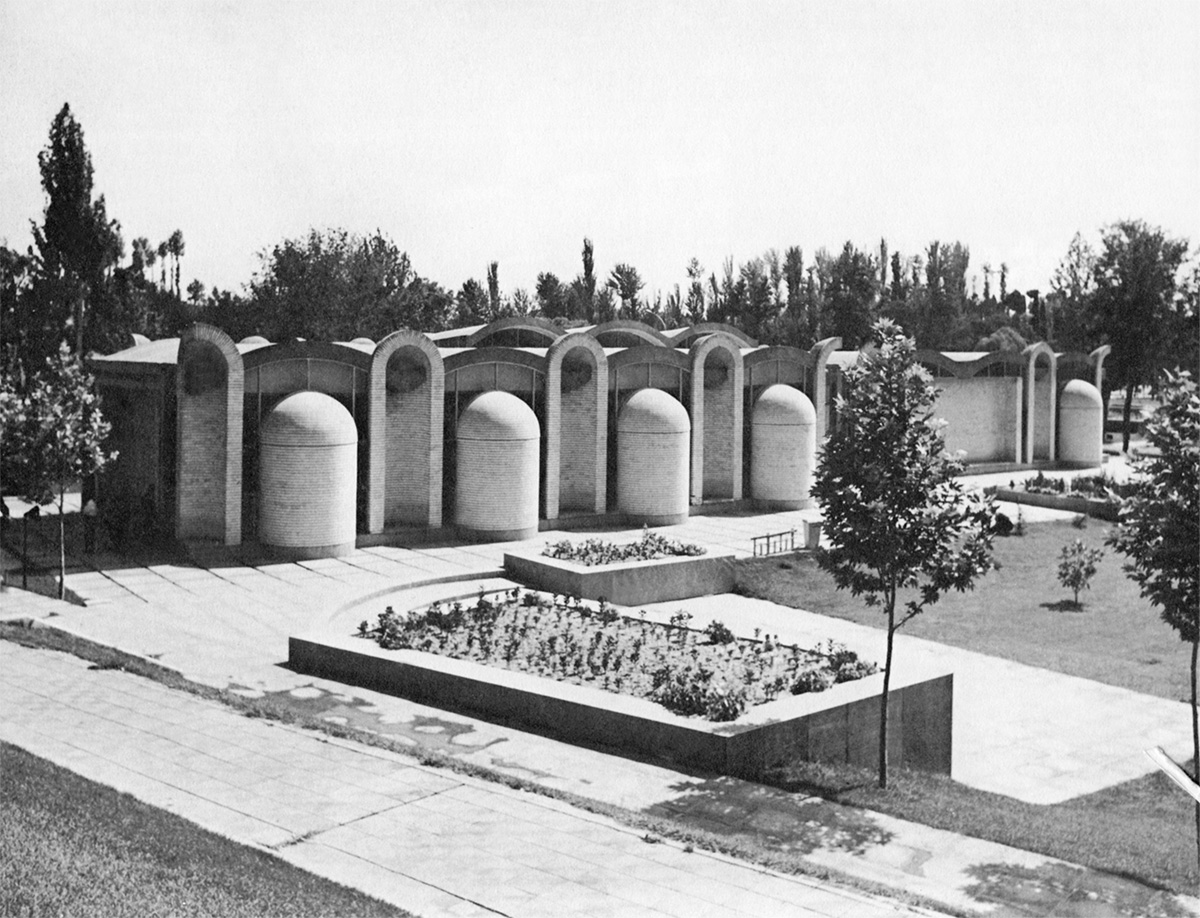

Masoud Jahanara. Kanoun Library, Isfahan, 1967-8

Hanieh Lotfipour: And what if your audience needs direct communication, Are you on any social media, and can your readers interact with you?

Amir Bani-Masoud: I have only a public account on Instagram where I share my experience and understanding of contemporary architecture in Iran. My Instagram username is @amir.banimasoud

Hanieh Lotfipour: Your newly published book, what is your favorite part, and your least favorite part?

Amir Bani-Masoud: Actually, it is very hard to answer. My book is more than an object to me. I feel like every book is a child to me, so I cannot say which part is my most or least favorite.

Hanieh Lotfipour: Eventually, is any noteworthy fact and point you are interested to add?

Amir Bani-Masoud: Thank you so much for the opportunity and for this interview. I hope my books will increase awareness of and inspire future research on contemporary architecture in Iran.

Hanieh Lotfipour: I appreciate your time and we are all looking forward to your new books in the near future.

All images © Amir Bani-Masoud's collection