In cities of conflicts, the damage of war has become the visual common denominator that defines the region of destruction and vulnerability. According to Jonathan Budd, “the term ‘Warchitecture’ describes the condition of war waged specifically as the destruction of architecture.” But the visual impact of such destruction is only the first stage in a long series of negative impacts which have social, cultural and humanitarian consequences. When the visual contact, or rather ‘touch’ with such conditions is made through the remains of destroyed architectural structures, it becomes understandable that it is architecture itself which is then responsible for the renewed existence, or the lack of, necessary elements that each society needs to restore and regenerate itself.

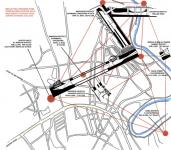

It should be possible then, and has become urgent around the world within the last decade, to explore the influence of war on architecture and vice versa, exploring the usability and conditions of architecture under the state of war and post-war environments. Initially this could be achieved by researching and investigating a site, for example, in Baghdad, subject to a condition of constant conflict throughout its modern history. From this one could chart the conceptual effects previous structures had on life in the city under conditions of war, siege and demolition.

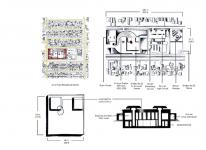

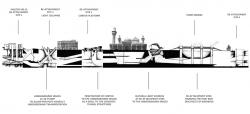

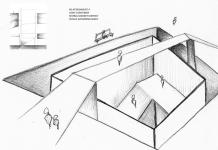

This could be researched from both the macro city level, and from the micro built-fabric level. The city of Baghdad therefore offers a case study at the macro city level, and Public Shelter No. 25 offers the equivalent on a micro level, the latter a shelter which was used during the First Gulf War as a family shelter for the residents of the Al-Amiriya neighbourhood in Baghdad. Public shelter No.25 was bombed in 1991 by US Forces smart bombs causing the deaths of over 400 people.

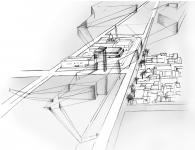

By exploring the efficiency of such structures and how they are used under constant conflict conditions we can then consider the contribution of such structures and the need for a new thinking in urban architecture – new site-specific structures - for cities having to live under this new age of conflict architecture. A more detailed look at the experiences of Shelter No.25’s victims, through their last, well documented, interaction with the architecture containing them, it should be possible to explore an architecture which, in this case among many others, acted as a form of death container that played a unique symphony during this mass execution. It is the potential transformation of such experiences into a space of renewal within the city which could play an important role in erasure and detachment; two poetic values of the city’s crucial and vital memory. The goal of such site specific architectures would be to propose strategies and architectures which could maintain the positive social and cultural aspect needed to recreate a new urban fabric, whilst performing under the pressures of attacks. War and conflict produce serious cultural and historical shifts.

2008

2010

ReeM Al-Rawi