Hodi, a disappearing ethnic group with more than a thousand years of tradition in the Old Brahmaputra Valley of the Bengal Delta, is facing fast-paced cultural erosion, socio-economic hardship and displacement from their ancestral domain. Socio-economic pressure combined with limited livelihood choices and lack of political representation has pushed numerous people to sell off their land and settle on Khas lands disengaging them from their cultural geography.

The thesis addresses Barar Char in Sherpur District of Bangladesh where some part of the Hodi community is still living along an oxbow lake. The project is hypothetical and derives its quality and depth from an Ethnographic Field Survey grounded in the oral tradition, everyday routines, and cultural practices of the Hodi people. These everyday experiences not only informed the ethnographic discourse but also were formative for the design approach throughout the thesis.

The research investigates the possibility of architectural intervention for an identity that was born and nurtured in this deltaic landscape and now faces the threat of extinction. The proposed architectural approach seeks to address the loss of their traditional values, spiritual beliefs and cultural practices which are under threat due to the pressures of modernity and displacement. By combining Neuroscientific, Anthropological, Medical, Economic, and Psychological Theories along with Participatory Community Design and Adaptive Architecture, the thesis imagines built environments that evolve with the needs of the community while considering their timeless cultural essence.

The proposed architectural plan has the intent of incorporating the Hodi's cultural heritage into the design framework, addressing both their socio-economic status and spiritual beliefs. The design also promotes intercultural communication with non-Hodi societies for social integration and shared understanding. The project seeks to sanctify the Hodi's cultural identity and create an interactive space that adapts without any cultural aggressions, placing architecture at the center of cultural continuity and social integration. It also acknowledges the ecological significance of Migratory Birds and the potential for Sensitive Waterfront Development which is a quiet but necessary requirement generated from the site's unique context.

Keywords: Reverse Contextualism, Cross-Cultural Identity, Cultural Aggression, Hodi, Indigeneity, Intergenerational Learning , Lo-Fab , Mandai Settlement , Neuro-Architectology , Tectonism.

2025

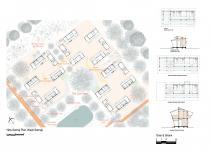

Residential Cluster:

a. 80 Housing Units – Flexible homes designed for vertical expansion and material adaptability, integrating Hodi traditions such as Uthan (inner courtyard), Dohol (outer courtyard), and Bondo (animal and poultry ground), while incorporating climate-responsive design for future generations.

b. Shared Kitchens & Animal Sheds – Spaces for collective cooking and livestock of one Ghar, echoing community livelihood.

c. Rice husking spaces for preparing rice beer and Dhenki Puja.

There are Five Clusters for five clans according to the demographic numbers. The clusters are introverted in nature.

Cultural & Social:

d. Community Hall – Venue for meetings, weddings and collective decision-making.

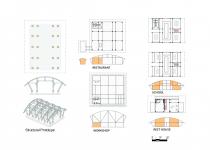

e. Samiti Bhaban (Administrative Building) – Houses offices, a handloom training center, a computer lab, and a community medicine center. Its form is modeled as a replica of the traditional Dera organization, reflecting local architectural and cultural identity.

f. Cultural Memory Center – An archive and exhibition space dedicated to oral history, rituals, and craft heritage. The form of this building contrasts with the larger masterplan, creating a visual focal point. Its shape is inspired by the Aakas-Kuppa (sky torch), which the community lights for their ancestors, symbolically conveying that their culture remains alive on Earth.

g. Dancing Ground & Ritual Forest (Jica Tree/Temple Belt) – Outdoor sacred spaces for puja, seasonal rituals, and performances. Occasionally, the area also serves as a Tulamuni (picnic) spot for the community. Spattered Religious Spaces strategically placed to emphasize the importance of empowering the Samaj, ensuring that each community cluster has at least one significant Hindu temple. This provides a sense of security and respects their dual cultural identity.

The shape of the Dera flows from micro to macro scale - household to public spaces, inspired by the community’s belief that this form provides visual comfort and strengthens cultural identity.

Education & Learning:

h. Pathshala (Pre-School, Primary & Night School) – An intergenerational learning hub combining formal education with cultural transmission. It facilitates youth club activities and is nestled within the existing forest, providing a sense of protection and calmness.

i. Workshop and Sales – Bamboo treatment, weaving, carpentry - sustaining the traditional craft economy.

j. Bamboo Music Garden – For recreation.

Livelihood & Market:

k. Haat-Bazar – Marketplace for daily needs and intercultural exchange.

l. Craft Development Agencies’ Hub – Training micro-enterprise support.

Public Amenities:

m. Rest House – Shelter for visitors, migrants or intercultural exchange programs.

n. Observation Facilities / Viewing Decks – Ornithology & eco-tourism linked to the Beel landscape.

o. Field- For public gathering during Charak Puja or Durga Puja, or for any fair or sports.

Waterfront & Ecology:

p. Ponds & Ghats – Designed for bathing, fishing, cremation rituals, and managing seasonal flooding. All water bodies are interconnected, reflecting the community’s traditional knowledge and water management practices. Mandar means cavity under a natural waterbody, generally used for making a fish trap at this locality.

q. Bamboo & Medicinal Forest Belt – An ecological buffer that supports traditional crafts, community health, and biodiversity. The bamboo belt prevents soil erosion, provides habitat for heron species, and reinforces the “one village, one product” concept by sustaining local craft resources.

r. Reserve Forest– Habitat for migratory and endangered bird species.

s. Community Agricultural Land – According to them, there is nothing individual. Everything is communal and should be distributed equally to individuals.

Although the site slopes towards the lake, land development is feasible due to the advantage of the existing government lake excavation project. The site’s layout has been derived from the contour lines along the edge of the water body. Three river offtakes around the site act as natural barrier channels, reducing flood risk and ensuring the settlement remains safe during seasonal inundation. Total site area is 42.5 acres.

“Hodi” came from the Arabic word “Hud,” which means people who live on the margin. And “Mandai” Means Human Being; actually is the name of an ethnic group. “Geram” means village in the Mandai Thar Language.

The Hodi possess a history of over a thousand years and are believed to be a branch of the Assamese Bodo. The Hodi once occupied the Brahmaputra flood plains and rich flat plains and subsisted on agriculture, fishing, and bamboo-based artisanal enterprises. The area was settled by a tribe known as the Mandai (a group with Indo-Mongoloid origin and Dravidian admix) before the settling of the Garos in the Mymensingh district. Over time, they intermarried and intermingled and two distinct branches of culture developed: one group, who migrated to the Madhupur Sal forest, were known as Kochh-Mandai and the other, after absorption amongst the Garo (or Mandi), as Hodi-Mandai. Hudi Nikni (clan of Koch) and Do’al Mahari (clan of Garo) have created this Mandai branch by intermarriage.

Although the Hodi have long been outside the pale of formal Hindu caste society, they firmly consider themselves Kshatriya (warrior class), and have even organized themselves into five Gotras (clans), following the mythical sons of a Kshatriya Raja- Goutam, Kapil, Autri, Angiraas & Kashyap. These endogenous frameworks continue to determine their conduct in ritual, marriage customs, and social organization.

In the first half of the 20th century, the Hodi demanded official confirmation of their Hinduised Kshatriya identity and agitated in 1921 Jamalpur Census, but were not recognized by colonial powers. This conflict over identity and legitimacy is an extension of the overall marginalization they have experienced—socially, economically and politically.

Historical accounts also suggest that the Hodi played a role in the Pagalpanthi movement at Sherpur following Tipu Shah's death, indicating their involvement in larger movements of resistance and socio-political consciousness in Bengal's colonial past. Their house form came from the shape Bow-Arrow which they called Teer-Dhonna. This can be merged with the contemporary movement of architecture.

Reverse Contextualism can be understood as a design approach where architecture does not merely adapt to its immediate surroundings, but instead asserts a distinct identity that reshapes how the context itself is perceived. Traditional contextualism prioritizes harmony, continuity, and blending with existing forms, materials, and social conditions. Reverse contextualism, by contrast, introduces a deliberate contrast-allowing the building or intervention to stand out as a new anchor. In this way, the design becomes a catalyst that redefines its setting, inspiring transformation while still remaining

rooted in cultural meaning.

For this project, which seeks to document and revitalize the endangered heritage of the Hodi community, reverse contextualism offers a strategic advantage. The Hodi people have long remained invisible within the larger socio-cultural landscape of Bangladesh. A purely contextualist response- quietly imitating vernacular huts or village layouts—risks reinforcing that invisibility. Instead, a reverse contextualist approach ensures that the architecture announces itself as a cultural landmark: bold, recognizable, and unmissable. By drawing from Hodi traditions, motifs, and ecological wisdom while presenting them in a contemporary architectural language, the project reframes their identity in a way that both the community and outsiders can engage with. The building becomes more than a shelter; it becomes a symbolic center that generates awareness, pride, and continuity. Over time, the surrounding settlement and social practices adapt around it, ensuring that Hodi culture is not only preserved but projected into the future. Reverse contextualism, therefore, aligns perfectly with the project’s ambition: to protect heritage while simultaneously transforming perception.

Name: Mehedi hasan

Studio mentors: Syed Abu Salaque, Naznia Momtaz, Kazi Zayed Titumir

Supervisor: Md Sazzad Hossain

Favorited 1 times