Abstract:

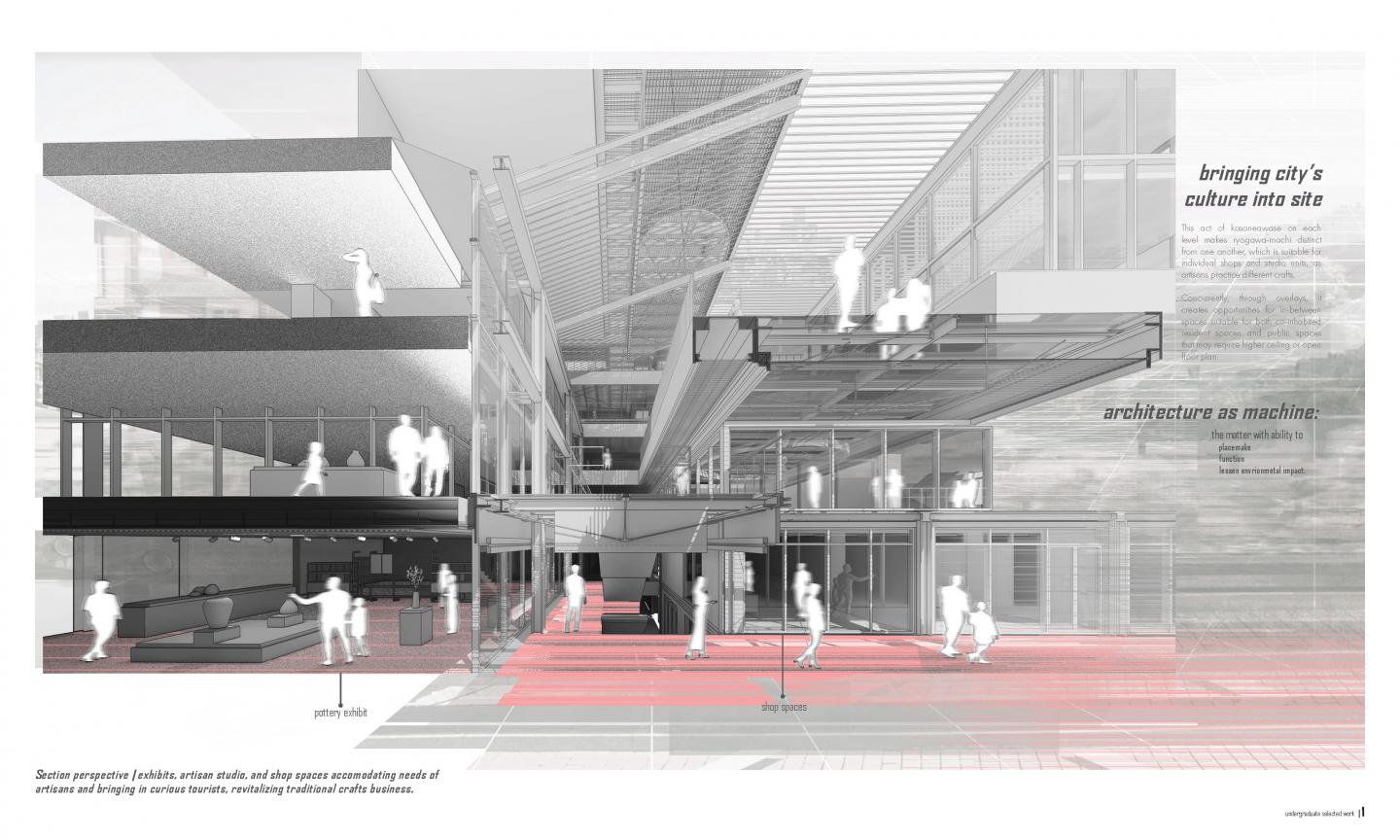

Ryogawa Machi Superimposition is for young Japanese artisans to live, work, and showcase their crafted artwork in Kyoto, Japan. The project will not only provide breathable apartment units but will also foster and encourage young artisans and their crafts to be publicized to the public within an interesting and adequate spatial setting with the public. The project is located between Ponto-Cho alleyway and Kiyamachi-Dori street. Ponto-Cho is famous for its well-preserved traditional townhouses and attracts millions of visitors per year. One of the major urban goals of this project is to and give opportunities for visitors to gain interest in traditional Japanese crafts. These goals are executed through two merging concepts. As the thesis title suggests, through superimposition and Ryogawa-machi.

Initial Interest and Motivation:

Upon arriving at Kyoto and walking around the city center of Shijō, I was struck by an atmosphere that felt rigid, to the point it was suffocating. I soon realized that this was because of the way the streets are organized. There is a large two-way lane with an endless stretch of commercial shops on both sides. The width of the pedestrian walkway is narrow and is about the width of two lanes. The long street seemed to continue endlessly, and after walking down the street for half an hour, I felt exhausted and uneasy since I could not comfortably stop to look around, in fear that I would block the flow of people.

The long street is called Shijō, a large two-way street that runs east to west across Kyoto city. Shijō translates to “Fourth Avenue” and is one of the busiest commercial streets in Kyoto. Through research, I found that there were blocks of smaller communities of merchants who made up the larger Shijō Street, mostly of humble backgrounds.

This discrepancy between the past and present state of Shijō intrigued me, and I felt that there was a need to delve deeper into how Japanese people had used and developed their communities in the past. I found that the way that many of Kyoto’s towns are organized is in a formation called Ryogawa-machi, meaning double-sided town.

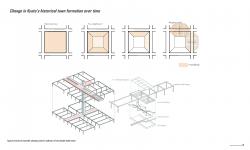

Gradual Change in Kyoto’s Historical Town Formation:

The original plan of Kyoto (Heian-Kyo, 800-1185 AD) envisioned a square block as one town, with houses lined up only on the east and west sides. However, as residents settled and adapted, the blocks expanded in all directions, transforming them into "four-sided towns."

The changes in town formation indicate that occupiable streets became central to people's living, and the final iteration of town formation became known as Ryogawa-machi, or "double-sided towns".

The concept of a “town” is much smaller in scale compared to the United States, as it is common for multiple double-sided towns to share a part of the same block.

Concept:

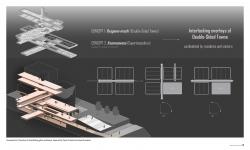

My thesis, Ryogawa-machi Superimposition, consists of two distinct ideas merged into one concept. First is Ryogawa-machi, meaning double-sided town, and the other is the superimposition. The second part of the concept is superimposition. Where ryogawa-machi is the noun, I consider superimposition to be the action verb that makes the concept a whole. Superimposition is “kasaneawase” in Japanese, which I interpret as “to overlay and interlock”.

Main throughfares then turn 90 degrees perpendicular and alternate floor to floor, creating interlocking overlays of several ryogawa-machi within one urban block. This way, each “town” is uniquely its own and gives residents more privacy and ownership of their space and craft.

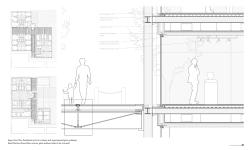

To amplify this uniqueness, main thoroughfares on each floor are made from transparent glass material, which allows for vaguely hinting at motion and solidifies the vertical shift in space.

2025

Program | Live-Work Apartment Complex for Young Artisans:

The second part of the concept is superimposition. Where ryogawa-machi is the noun, I consider superimposition to be the action verb that makes the concept a whole. Superimposition is “kasaneawase” in Japanese, which I interpret as “to overlay and interlock”.

As explained previously, Ryogawa-machi is tied to a community of townspeople living across two sides of a street, making one small “town”. Often, the Ryogawa-machi communities had shops facing one another toward the shared street. Going off this idea, every floor has a main corridor that acts as a street inside the town.

Live-Work Typology Accommodating Needs of Young Artisans:

The lower floors have shop-atelier spaces facing the main thoroughfare, while the upper residential floors have a shared corridor with units on both sides. This rule applies only when there are public or communal spaces. For example, on the basement level one, the exhibit space has entrance doors facing the east-west corridor, separate from the main thoroughfare that runs north-south for shops.

Responding to the value of autonomous co-inhabitation, each floor level is its own reconceived Ryogawa-machi. Together, they make up the larger community of artisans, revived through sharing thoughts in communal spaces.

Amy Kwon

Advisor: Professor Il Kim