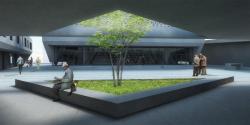

Kulliye, a complex of mosque and supplementary buildings with various functions, used to be a prominent public space in the Ottoman city lacking Western type plazas. However, the Ottoman kulliye is typically introvert and does not connect with the surrounding urban tissue. The modern kulliye designed for the competition is reinterpreted as a project fusing with the neighborhood where the closed, semi-open and open spaces are open to public use.

Traditionally prayer is not performed beyond the mihrab, the wall facing Mecca, accordingly the mosque is shifted to the site border, in order to maximize the open space to pray on.

Remaining spaces besides the mosque were placed around the mosque to form a courtyard opening up to Halide Edip Adivar Street while providing isolation from the traffic noise of Piyalepasa Boulevard.

The primary pedestrian entrance to the courtyard was planned north of the mosque and the most frequently used spaces such as, reading hall, charity society, men’s ablution room and WC were located alongside. Education spaces were solved in a separate building that is secluded from the courtyard with the plant pot in front. Similarly, women’s ablution room and kitchen, as well as the morgue were separated.

Residences entered from Halide Edip Adivar Street were solved on the upper floor, along the neighboring multi storey buildings on the north side, in order to provide privacy.

Wide stairs and an elevator were planned to enable pedestrian connection between Bahçecik Street and Halide Edip Adivar considering people coming to prayer from both Bahçecik Street and the other side of Piyalepasa Boulevard.

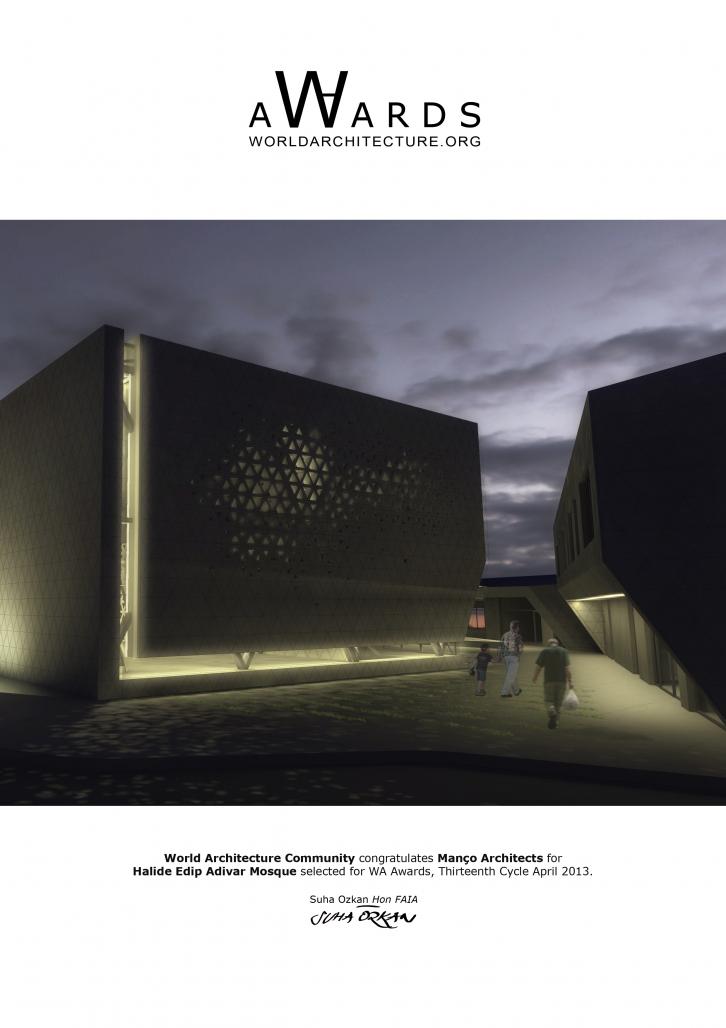

Considering the absence of Islamic spatial prerequisites, the mosque was shaped with a contemporary attitude independent of formalistic clichés of classical Ottoman architecture predominant in Turkey.

The “rectangular plan” that is one of the few common aspects of Islamic architecture based on the rule of lining up towards Mecca during prayer, and the “single large inner volume” in Ottoman architecture were the two classical principles followed. Nevertheless, in pursuit of a distinct form, a dome was not designed, especially considering the availability of different contemporary methods of covering wide spans.

The side façades of the mosque were separated from the ground and the mihrab with a narrow glass strip, in order to emphasize the continuity of the praying lines inside and outside as well as the central role of the mihrab. Consequently, the fundamental function of the mosque being “a wall directing towards Mecca and a shelter for prayer lines” was highlighted.

Women’s praying area is designed as a projection covering the entrance of the mosque. Likewise, the residence floor is also planned as a wider slab blocking the harsh sunshine and creating a shaded semi open area underneath. The same effect is provided with canopies uniting with the façades of the remaining buildings.

The minaret being the foremost symbolical element of Islamic architecture was designed as a standalone structure in order to retain the simplicity of the mosque mass.

A pool was placed alongside the mihrab to stress the symbolism of water that is described in Quran as the “source of life” whereas reflecting the façade on its surface.

A steel frame covered with glass, insulation layers and prefabricated façade panels is proposed so that the mosque represents contemporary architectural design, as well as building techniques.

The steel frame was designed to result in a pattern on inner and outer façades in reference to the structural elements such as domes and arches shaping the interior in classical Ottoman mosques.

Large transparent openings on façades were not preferred due to the moderate illumination level Turkish people have accustomed to in the Ottoman style mosques and the disturbing effect of glare on praying. Mihrab was enlightened with the light diffusing through the surrounding glass band.

A simplified reinterpretation of geometric ornaments of Islamic art was achieved by using equal triangle panels sized according to the steel structure. Daylight was allowed inside through holes opened on those panels during production. The openings were placed according to the spaces behind however a random effect was created with their varying sizes. The same pattern was also applied on interior walls of the mosque.

The façades and roofs of the other buildings were also covered with the same layer consisting of fiber cement panels, which are very durable and do not need any maintenance. The effect of a continuous plane surrounding spaces was created with concrete pavement having a similar texture.

Stripes of grass facing Mecca were placed on the courtyard to enable orderly lining up of praying Muslims. Same lines were continued on the carpet floor covering of the mosque to underline the unity of inside and outside.

In order to provide a constant inner air quality inside the mosque, an artificial HVAC system supported by an air source heat pump running underneath the floor was proposed.

Cross ventilation in other buildings than the mosque will be enabled through operable windows and ceiling ventilators.

Water consumption will be reduced with rainwater and grey water use systems installed.

Energy load of the buildings will be further decreased by the use of LED exterior and interior lighting, as well as motion sensors.

2012

2012

5509m2, 4 storeys, composite structural system

Ali Manço, Zuhtu Usta, Deniz Tatlidede, Zeynep Ceren Erdinç, Yagmur Akyuz

Halide Edip Adivar Mosque by Manco Architects in Turkey won the WA Award Cycle 13. Please find below the WA Award poster for this project.

Downloaded 225 times.

Favorited 1 times