“A nation deep in denial loves the imitation, pastiche and sameness of look-alike architecture. Additions made with the brain engaged, however, build on the truth that what matters is not looks but meaning. What matters is what the new and the old in their differing expressions say together about the evolving subject matter, the way the new and the old are brought to collaborate across their difference to make vivid what needs to be realized today.”

Paul Spencer Byard / Harvard Design Magazine, Issue 23

Adding to a suburban house does not entail a fancy program and there is no picturesque setting or urban density to be reckoned with. Rather the mundane nature of this project lends itself to a focus on the act of addition the question of old versus the new and the meaning of preservation versus evolution. We began with the notion that evolution and growth is at the core of any architectural endeavor and that every project is an addition or an extension of its context. This notion generates an understanding of being contextual as being prone to mutation and growth.

In the same way we view a project as an extension of its surrounding, we view the act of designing as an extension of an already accumulated professional knowledge and not as a tabula rasa operation. As such, we look at our projects and our operations in the context of similar precedents and typologies. However when we look at architectural typologies we don’t look for the rigid set of fixed rules, rather we examine the moments where these fixed rules can break or mutate. It is precisely these moments that we can use to our advantage when we engage new environments, programs and constraints. In this case we looked at the typology of suburban housing and the typology of addition.

The typology of addition is in itself the typology of mutation. When looking at different precedents at the building scale it’s easy to find the modernist approach that contrasts the old and the new, the neo historicist approach that borrows from the old to cover the new, the archeological approach of the old being covered by the new and the preservationist approach of the new occupying the old. However only when looking at the urban scale did we find the typology of addition where the new and the old simultaneously impact one another. The new carves into the body of the old, redirecting flows and at the same time being redirected by the flows and matter of the old. When looking at the evolution of urban typologies through time, it becomes clear that this is not a morphological and definitely not a stylistic categorization of type; rather it is a performative one. It is a typology that can only be defined by relations of weak and strong structures, both physical (voids, highways) and non physical (social, economical).

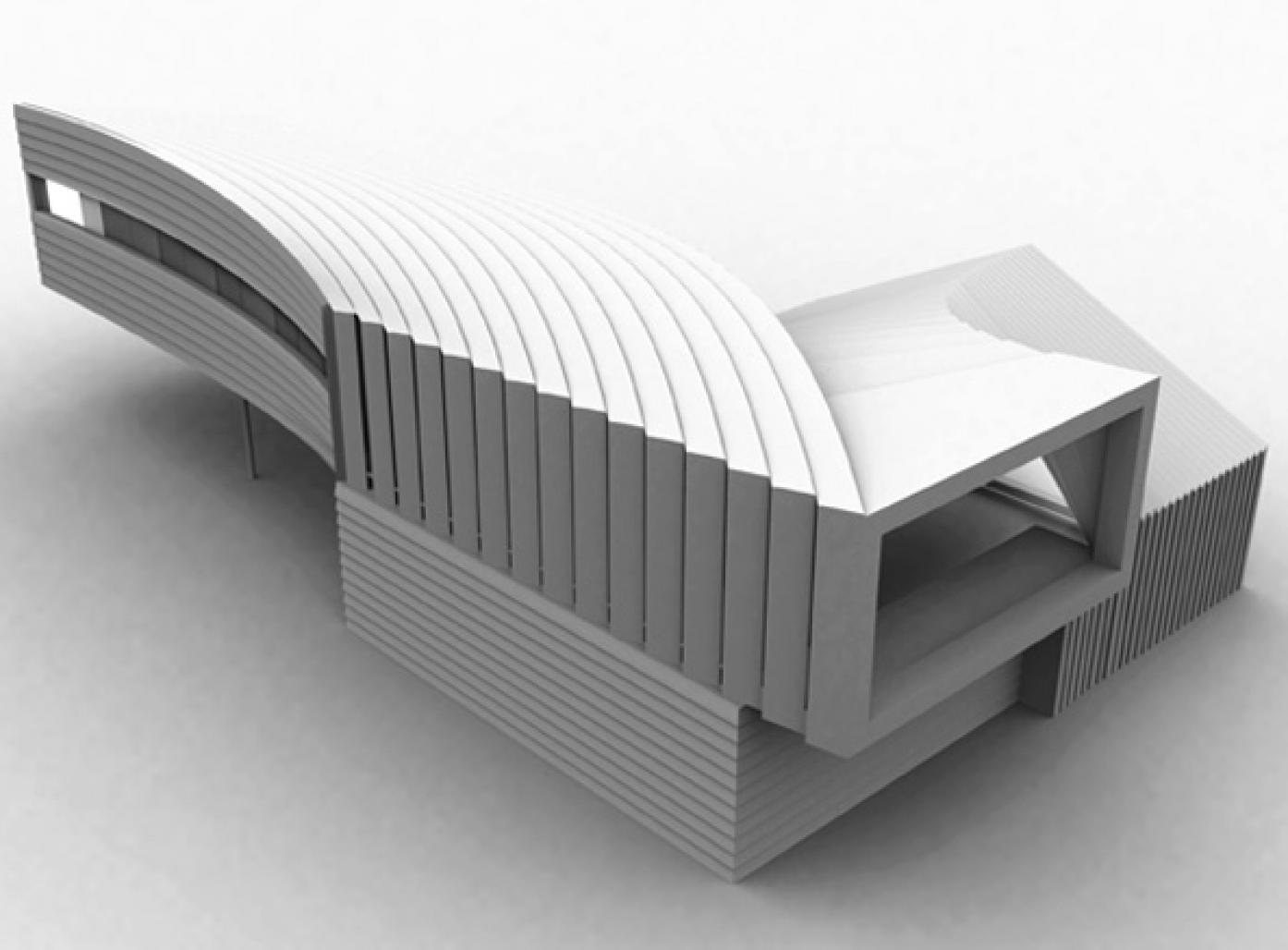

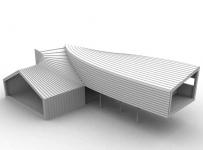

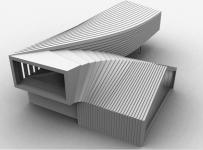

In the typology of the suburban house there are two primary structural systems, the vertical structure (stemming from the foundations and holding the walls) and the triangulated structure (holding the pitched roof). This structural logic of stacking the two disjointed systems one on top of the other can be found in different environments and dressed in different styles, but remains the essence of the American suburban house typology. When looking for the weak points of this typology, the points where mutation might happen we were intrigued with the fact that these are indeed two disjointed structural systems, each performing its own task.

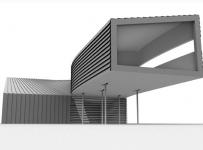

Following these findings we located the extended volume so that it is hovering above the existing vertical structure leaving the footprint and foundation intact. The pitched roof structure is absorbing the mutation caused by the extension. The joint between the old and the new is not only indicated on the exterior volumes but is also registered in the interior of the house where a double height space is created and the stairs are located. Despite the double curvature of the volumes they are made of simplified surfaces that a

2007

.jpg)