Submitted by WA Contents

Koolhaas’ Retroactive Manhattanism

United Kingdom Architecture News - Dec 23, 2013 - 22:47 10646 views

With OMA’s latest project, De Rotterdam, Netherlands, has Rem Koolhaas found a local variation on the ‘Manhattanism’ that he explored in his landmark book Delirious New York?

Rotterdam was the first European city to adopt the North American idea of an exclusive pedestrian retail zone. It was completed in 1953, following the destruction of much of the city in World War II. The city has often been an agglomeration of concepts, pragmatics and solutions that have found great success elsewhere. Its architecture seems similarly obtuse, a collection of strange forms or bold ideas.

Rem Koolhaas, through his Rotterdam-based Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), has recently unveiled the studio’s latest offering – De Rotterdam, Netherlands. This office building sits in among a plethora of architectural objects that ratify the notion of urban agglomeration. The tower – one of the largest in Europe standing at 150 metres tall and 100 metres deep – is a simple form, consisting of four staggered office blocks rising from an elevated platform. It seems quite in keeping with other recently completed OMA projects: Milstein Hall, Cornell University and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

OMA’s de Rotterdam, Netherlands building (Michel van de Kar).

De Rotterdam’s continuous aluminium mullion cladding system is reminiscent of the former Twin Towers World Trade Center, as its elongated, slender form intensifies the project’s verticality and adds weight to the notion of the ‘vertical city’, an aspect Koolhaas has often strived to achieve in a number of projects.

With its 70,000 square metres of office space, 240 residential units, 285-room hotel, conference facilities, car parking and hospitality, there is a fusing of programs that is quite synonymous with OMA. It also has a quantifiable connection with the city of New York and Koolhaas’s postulations on hyper-density through ‘Manhattanism’, which he explored in his book Delirious New York (1978).

Front cover of Delirious New York by Rem Koolhaas.

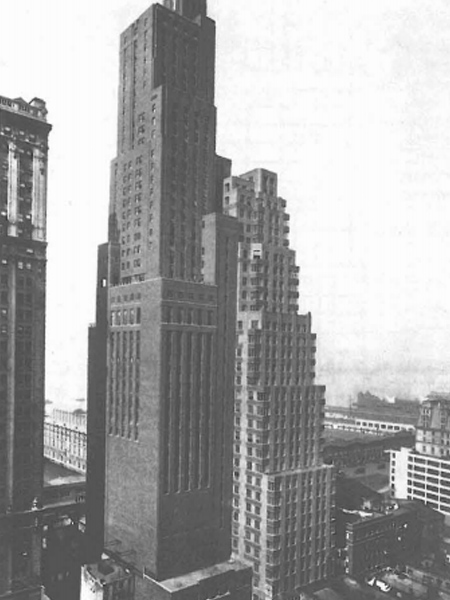

The Twin Towers adorn the front cover of Delirious New York, but the manifesto goes beyond merely the envelope in its identification of the ‘definitive instability’ of the Downtown Athletics Club (1930), a project designed by Starrett and Van Vleck. Its small rectangular footprint is repeated upwards 38 times; its vertical striation informs the relatively conventional floor plans.

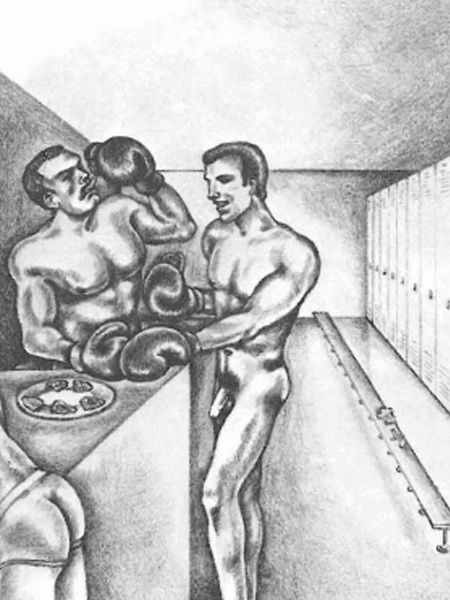

The floor plan of the ninth floor of the Downtown Athletics Club.

Koolhaas’s focus, in Delirious New York, was on the ninth floor: “Emerging from the elevator on the ninth floor, the visitor finds himself in a dark vestibule that leads directly into a locker room that occupies the centre of the platform, where there is no daylight. There he undresses, puts on boxing gloves and enters an adjoining space equipped with a multitude of punching bags (occasionally he may even confront a human opponent),” he wrote. “On the southern side, the same locker room is also serviced by an oyster bar with a view over the Hudson River.” This was the defining image Koolhaas wanted to portray: “Eating oysters with boxing gloves, naked, on the ninth floor – such is the ‘plot’ of the ninth storey, or the 20th century in action.” It was a phenomenal socio-cultural and architectural critique using the programmatic elements of one building in one city to identify a much broader claim.

“Eating oysters with boxing gloves, naked, on the ninth floor…” Lower Manhattan’s Downtown Athletics Club, founded in 1926.

Koolhaas outlined that across every floor there were almost binary programmatic actions that resulted in the perceived floor plan as merely an abstracted composition of activities that “describes, on each of the synthetic platforms, a different ‘performance’ that is only a fragment of the larger spectacle of the Metropolis”. In synopsis Koolhaas stated, “In the Downtown Athletic Club, the Skyscraper is used as a Constructivist Social Condenser: a machine to generate and intensify desirable forms of human intercourse.”

New York’s famed Downtown Athletic Club.

This is a defining aspect in the career of OMA: social condescension to instigate interaction through the cross-pollination of programs.

De Rotterdam is essentially a conventional, ‘cheap’ office building – far removed from its Downtown equivalent of abstracted programs and convoluted happenstance – but in its location, has Koolhaas found ‘Manhattanism’ in his own backyard? Are the obtuse programmatic forms of the Athletics Club now the myriad architectural objects and empty office towers interacting on an urban level?

In Koolhaas’s competition entry for Parc de la Villette, Paris (eventually won by Bernard Tschumi for his ‘Follies’), the section of the Downtown Athletics Club was rotated 90 degrees and overlaid on the site as a floor plan. The site was, therefore, divided in the striated banding of programs in an attempt to, according to Koolhaas, “create maximum permeability through each programmatic band”. It was devised to encourage interactions. It was to become a congested, horizontal sprawl.

OMA’s de Rotterdam, Netherlands (photo: Philippe Ruault).

Does Rotterdam, then, appear as the vestiges of Manhattanism as its own retroactive manifesto? Has the sectional cut of the Club become the urban plan of Rotterdam?

> via AustralianDesignReview