Submitted by Berrin Chatzi Chousein

Turner prize winner Laure Prouvost: ’I’m very strange’

Turkey Architecture News - Dec 04, 2013 - 00:42 6626 views

The Frenchwoman who made her winning installation while heavily pregnant explains why Britain is better for artists – and why teacups with comedy buttocks are the key to her victory

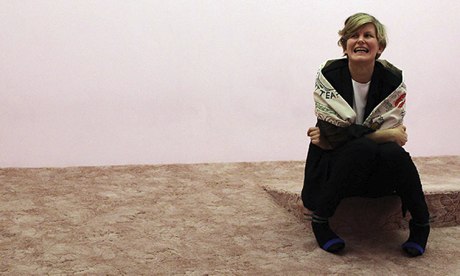

'Who cares about the difference between fantasy and reality?' … Laure Prouvost. Photograph: Peter Muhly/AFP/Getty

"I went to the betting shop this afternoon," says Laure Prouvost, "to put a bet on the Turner prize." You could have made a tidy sum, I say, backing yourself to win at 6-1. "Oh no, I wasn't going to bet on me. I was going to bet on Tino Sehgal. I was so sure he was going to win." But his odds were rubbish: as the favourite, he was 7-4. Just as well the bookies had stopped taking wagers by the time she arrived.

It's nearly midnight in an upstairs room at the Custom House restaurant in Derry, and the 35-year-old French video and multimedia artist hasn't yet got used to what happened a few hours earlier: when she won the £25,000 Turner prize. "I expected a really quiet night rather than … "

"Globally trending on Twitter?"

"Exactly."

Prouvost was trending because she is three things Turner-prize winners rarely are: French, a woman, and the mother of a baby two months old. Celeste, having been photographed in the arms of her prize-winning mother, is now tucked up in bed, while Prouvost – along with her parents, her museum curator of an English husband and friends – has been celebrating with whiskey and salmon, while wearing a tea towel featuring objects from her show as a scarf.

'Thank you for adopting me' … Prouvost winning her award. Photograph: Peter Morrison/AP

When she climbed on stage to receive the award from Irish actor Saoirse Ronan, Prouvost was clearly struggling to control her shock. "Thank you for adopting me," said the London-based Frenchwoman who has lived in Britain for the past 17 years. But if the award is a recognition of hard labour, it's fitting Prouvost won. Were the other shortlisted artists – Sehgal, David Shrigley and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye – heavily pregnant when they worked on their entries? I think not. Sehgal, the anti-arts-objects artist, merely hired two interpreters to stand in an otherwise empty gallery waylaying mildly irritated visitors and suckering them into conversations about the market economy.

All very clever, in its ontologically parsimonious critique of commodified culture. But, downstairs in another gallery, Prouvost was filling her space with more and more stuff, like an anti-Sehgal. Her installation Wantee was commissioned by Grizedale Arts and the Tate to feature in a Kurt Schwitters retrospective at Tate Britain earlier this year. For it, Prouvost built a grubby cabin in the Lake District, where her fictional grandad ostensibly lived, jamming it with junk and capturing it all on film.

For the Turner prize show, at the former British army Ebrington Barracks, she made the installation – already a kind of crammed junk shop of the human heart – more crazily sprawling. She expanded the table at which visitors sit, made more teapots and cups with cheeky bottoms (of which more later). "What is wrong with me?" Prouvost says, still giddy from her victory, and poking fun at her own show. "Why do I have so many objects? There are already so many objects in the world. Maybe I should stop." That, no doubt, would be Sehgal's advice.

Tea and tunnels … the dining table in her installation Wantee. Photograph: Laure Prouvost/MOTInternational/PA

Prouvost created more footage for her endearingly dotty film. The centrepiece of Wantee, it purports to tell the unlikely story of her grandfather, a conceptual artist who was a friend of Schwitters, the exiled German collagist and performance artist. Her grandfather's last artwork, we learn, involved digging a tunnel underneath his home, down which he eventually disappears. This unnamed grandfather is portrayed as an art-world boob living in a squalid shack, just as Schwitters did. He wants to be a conceptual artist, but doesn't know how.

"He keeps getting it wrong," says Prouvost. "He misunderstands everything." Why is the show called Wantee? "Because Schwitters had a girlfriend who asked visitors if they wanted tea so much that he ended up calling her Wantee. Do you want tea? Want tea?" Sounds patronising. "Oh, it was a bit macho, but very much of its time."

Prouvost built another room off the main suite, a kind of Wantee 2, in which you climb through a hole in the wall and struggle up a crazily tilted carpeted floor. On a monitor, you then watch Prouvost tell you (in her breathy, grammatically wonky, French-accented English) about her grandmother's dreams, over a dizzying montage. "I made this to present the female side to the story. She shouldn't always be hidden behind this master artist."

But hold on, are these characters based on reality? "My grandfather was a conceptual artist," she says. "And he was friends with Schwitters." Really? She doesn't give her grandfather a name, so it's impossible to check. "Really." Oh come on, you say your grandad disappeared into a tunnel beneath the ghastly hut where he lived and hasn't been seen since – that's nonsense, isn't it? "But what is the difference between fiction and reality?" she smiles. "And who cares anyway? It's up to you. Do you want to believe? Wouldn't you like to believe?"

I suggest this grandfather is partly a projection of Prouvost's own imagined inadequacies. "That's right!" she says. "I misunderstand everything. Why are we here? What do I do? Words? I don't do words! For years, I misunderstood a lot of English words, and you go off-piste, your imagination steps in. If you misunderstand someone's art, you create a new art. I am very strange like that."

Prouvost with some of the objects from Wantee. Photograph: Martin McKeown

Prouvost is strange, but in a good way. The French artist did something her compatriots hardly ever do: chose the British art world over her homeland's. She came here aged 18 to study art at Central St Martins in London. ("I can't think of any other French artist who did that," says Tate director Nicholas Serota, when I buttonhole him in the hotel lift. "She's exceptional.")

So why did she come to Britain? "I first came when I was a kid and loved it – people with pink hair, they seemed so free. I felt you can be who you are without the pressure of being judged. You can't really do that in France." Born near Lille in 1978, she "had a great upbringing. My parents are very open-minded and really wonderful. But there is also a system in France for artists: you need to become part of the group, believe in the same thing. Here, in a beautiful way, you can be yourself. When you leave your country, you become a bit of an adventurer. You have to manage whatever way you can."

Prouvost worked for a while as an assistant to John Latham, the late British conceptual artist whose work, on the surface, seems more akin to Sehgal's than hers. After all, it was Latham who organised a party at which guests chewed at the pages of critic Clement Greenberg's book Art and Culture; the remains were then fermented, distilled and returned in a test-tube to the St Martins library.

In 2010, Prouvost made I Need to Take Care of My Conceptual Grand Dad, a film in which she smeared body lotion over the pages of a Latham monograph. As with Wantee (intended as an exploration of "generational divides and artistic legacy"), the work examined the mentor and the mentee, and what the latter owes the former.

Prouvost is exceptional in another way: I'd never found conceptual art funny until I saw Wantee. In the film, Prouvost's voice notes sadly that her grandad "didn't really like conceptual art – he liked making bottoms". These bottoms adorn the novelty cups that litter the table on screen and at which viewers sit (it's a simulation of the on-screen simulation). Perhaps there's just something inherently funny about the way a Frenchwoman says "bottom", but I suspect it's more than that: it's the gap between aesthetic aspiration (the seriousness of conceptual art) and the ridiculously pervy (making teacups with buttocks).

Later in the film, we see Prouvost holding a canvas, part of her grandfather's collection. "It is very useful as a tray," she says, in her melodic voiceover, "but not so much as a painting." It is a funny, sad world she has created, filled with objects nobody could want, teeming with art that is useless as art. In what we are to believe is her grandfather's filthy old cabin, sculptures double as doorstops, paintings are used to patch holes in the walls.

Prouvost, with her husband, shows her surprise as she is announced as the winner. Photograph: Paul Faith/PA

Her art seems both very British and very French. British because it's steeped in melancholy and humour. "I love British culture," she says. "I love the irony, the humour, the black humour. I feel very attached to it." But it's also very French in its exploration of philosophical ideas, perhaps sub-consciously channelling her countryman Jean Baudrillard's work on simulations and simulacra.

Incidentally, the tunnel down which her grandfather disappeared was heading to Africa. He may by now have started a new life there, as a shy, inept conceptual art mole. Prouvost hopes not. "I want my grandad back, you see," she says, facing down my sceptical look.

In an attempt to change the subject, I ask one last question: what are you going to spend the £25,000 on? "A VIP centre for my grandad for when he comes back," she says deadpan, pulling that tea towel round her shoulders and turning to head back to the party. "He's lived in a shack for too long."

• The Turner prize 2013 exhibition is at Ebrington Barracks in Derry until 5 January 2014

> via TheGuardian