Submitted by WA Contents

MOSHE SAFDIE:Global citizen

United Kingdom Architecture News - Nov 21, 2013 - 11:50 6739 views

Writer Christopher Hume

Photographer Peter Ash Lee

Moshe Safdie may not be your average starchitect, but he is definitely an architect and certainly a star. The Israeli-born, Canadian-raised, and Boston-based practitioner has designed dozens of celebrated buildings around the world—everything from museums, libraries, and art galleries to residential towers, memorials, and airports. He can unquestionably claim his place in the pantheon of architectural greats, yet he has eschewed the sort of attention lavished upon contemporaries such as, say, Frank Gehry and Rem Koolhaas.

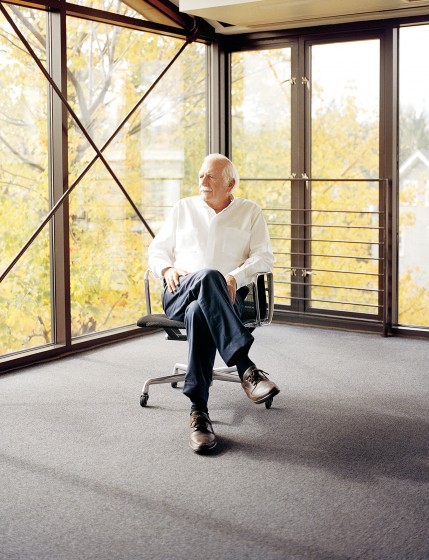

Ensconced in his elegant, ivy-covered office studio in Somerville, Massachusetts, the silver-haired architect is the very picture of someone at ease with himself. Safdie is a man who has a place in the world and enjoys it. Indeed, his career was launched in spectacular fashion nearly half a century ago when Habitat ’67, the revolutionary housing complex he designed based upon his undergraduate thesis, was constructed as part of Expo 67. The landmark world’s fair held in Montreal in 1967, whose theme was “Man and His World”, attracted 50 million visitors and changed Canada’s perception of itself.

The residential complex is one of few structures built for the storied event that still stands. It is fully inhabited and remains as striking today as it was when it first appeared. Safdie, who recalls Canada’s great centennial celebration as “an amazing fairy tale,” maintains a penthouse apartment in Habitat to this day. Though Habitat never achieved Safdie’s goal of reinventing affordable living for crowded cities, it provoked much discussion and brought him to international attention while he was in his 20s. Each of Habitat’s 158 units was made of prefabricated concrete assembled on a site next to the St. Lawrence River, not far from downtown Montreal.

“I look at Habitat in two ways: as an idea and as a building,” Safdie explains. “I’m amazed at how well it has aged. And I’m amazed I got away with it. I was a kid. I look at it now almost as an outsider. It’s still an idea that has yet to happen. But if you look at what kids are doing now, it’s clear it’s an idea whose time could well have come.”

As Safdie also makes clear, Expo 67 was a unique moment in the history of Canada, of Montreal, and of world’s fairs. “It was a moment of unity of purpose, a moment that transcended local aspirations,” he says. “By contrast, the 1976 Olympics in Montreal were a Quebec moment. Expo was a remarkably optimistic moment. It was the last world’s fair that dealt with ideas—since then, they have become dominated by corporate interests.”

And for the young McGill University architectural graduate, Expo and Habitat were to be a defining episode; he was suddenly thrust into the global limelight, and more importantly, it seemed anything was possible. The hope would quickly fade. Within a decade, Quebec was in the hands of a separatist government dedicated to taking it out of Canada. Businesses fled down Highway 401 to Toronto. Montreal would never recover.

But by then, Safdie had already interned in Philadelphia with famed modernist architect Louis Kahn. In fact, in 1964, at the age of 26, Safdie had opened his own practice. And for two decades after Habitat, Safdie devoted his time to teaching. In 1978, he moved his office to Somerville, just a short walk from Harvard University, where he served as the director of the urban design program at its Graduate School of Design. From 1984 to 1989, he served as the Ian Woodner Professor of Architecture and Urban Design. In these positions, he was free to follow more theoretical pursuits. His interest in cities, for instance, led Safdie to write The City After the Automobile: An Architect’s Vision, a 1997 book that explores how we might deal with the great curse of the age, our addiction to the car.

“I LOOK AT HABITAT ‘67 IN TWO WAYS: AS AN IDEA AND AS A BUILDING,” SAFDIE EXPLAINS. “I’M AMAZED AT HOW WELL IT HAS AGED. AND I’M AMAZED I GOT AWAY WITH IT. I WAS A KID. I LOOK AT IT NOW ALMOST AS AN OUTSIDER.”

He makes no secret of his concerns about where he thinks North America is headed. “I don’t like what I see,” Safdie admits. “I don’t like where it’s going—social segregation and gated communities. We are building completely sprawled-out suburban conurbations. I don’t see any positive in suburbia. The best places in the U.S. now are revitalized 19th-century cities such as San Francisco, New York, and Boston.” That’s why he argues—only half-jokingly—“that it’s time to make urban design a respectable activity.”

As Safdie sees it, the architect’s job is not so much to create landmarks (though sometimes that’s appropriate) but to enhance the urban fabric. That’s one reason he admires Asian cities, and Singapore in particular, where his remarkable and massive Marina Bay Sands integrated resort complex includes three curving towers topped with an enormous three-acre rooftop garden. Perhaps because they have to put so much into so little space, Singaporeans, unlike North Americans, are “extraordinarily invested in their infrastructure.”

“Projects should be evaluated as part of the public realm,” he says. “We need to ask how a complex affects the public realm in terms of access and how it affects public life. That’s why urban design should be integrated into the study of architecture. Architects must allow the context to inform their work.”

Most impressive, says Safdie, is that the Asians accomplish all this at breakneck speed; the Marina Bay Sands expo and convention centre complex, which covers 1.3 million square feet, was built in just four years. (The entire integrated resort—which includes hotel, casino, retail, museum, and promenade—is 10 million square feet in size.) As he points out, in Canada or the United States, a similar-sized project would have taken a decade or longer to complete.

Safdie has a large number of projects to his credit across North America. One he remembers with special fondness is the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, one of his first major institutional commissions. The elegant glass and stone structure sits across the river from (and echoes the Gothic features of) the Canadian Parliament Buildings. Opened in 1988, the gallery combines the architectural gravitas expected in the national capital, but with a sense of openness, accessibility, and welcome expected in contemporary cultural institutions.

The extensive use of glass would have seemed wildly inappropriate in an earlier age of museum building. All that light would have driven curators to distraction, and it isn’t good for artworks. That hasn’t changed, but today curators understand the need for buildings that are unintimidating and even inviting to the public. By acknowledging the historic buildings that surround the gallery, and being inspired by transparency rather than opacity, Safdie managed to refer to the past while bringing it into the future. He also opened up the institution, quite literally, to the public gaze. In this way, the fortress becomes a pavilion. “My wife [photographer Michal Ronnen Safdie] thinks the National Gallery is one of my best buildings,” Safdie says. “I’m very fond of it—it’s kind of a landmark for me. I was also lucky to have two great clients, Pierre Trudeau and [former director of the National Gallery] Jean Boggs.”

Boggs ran the gallery from 1966 to 1976 and then left to teach at Harvard. In 1982, Trudeau appointed her chair and CEO of Canada Museums Construction Corporation, which was set up to oversee the construction of both the National Gallery and the Canadian Museum of Civilization (called the National Museum of Man at the time).

Trudeau, a friend of Safdie’s (the two travelled through China with a delegation that included the late, great Canadian architect Arthur Erickson in the 1970s), had a strong interest in culture and made the building of the two institutions a national priority. The gallery has stood the test of time. Safdie used the opportunity to create a civic landmark as well as a cultural monument, a place that serves both the art it displays and the people who see it.

This attention to people and program is a hallmark of Safdie’s architecture. That may sound obvious, but it’s not necessarily the case; in a profession as full of mega-egos as it is megaprojects, users are frequently overlooked if not outright forgotten. In an age where technology has allowed architecture to become more sculptural than ever, some architects find it difficult to not get carried away with the grandeur of their own visions.

As Safdie has said, “Architecture is not about building the impossible, which we can do if we have enough money and enough tools and enough computers. It is about building what is appropriate and about attaining beauty through such an approach. I describe this premise as ‘inherent buildability’, and I believe it is central to what I do.”

Even his most exceptional, demanding, and sensitive projects, such as Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum in Jerusalem, are mindful of their contextual responsibilities. That remarkable structure is built into a hill that looks onto the Ein Kerem valley. It is an intense, if sparse, landscape, one with which the museum is fully integrated. In one of the most dramatic moves in contemporary architecture, and one that many consider Safdie’s finest moment, a large triangular space runs through the complex and then extends over and into the valley. As Safdie has stated, “The building is bursting out toward the north, a volcanic eruption of light and life.”

WHILE LIVING IN ISRAEL, SAFDIE ORIGINALLY INTENDED TO STUDY AGRICULTURE AND HELP ESTABLISH THE FLEDGLING NATION. BUT ONCE IN CANADA, AN APTITUDE TEST REVEALED THAT HE’D MAKE A GOOD ARCHITECT.

For an architect, projects like Yad Vashem come along once in a lifetime, and, in Safdie’s case, the complex received widespread praise. One of the most unexpected results of his holocaust museum was an invitation to design the Sikh centre, Virasat-e-Khalsa, also known as the Khalsa Heritage Memorial Complex, in the city of Anandpur Sahib in Punjab, India. Though Safdie knew relatively little about Sikhism, he was well equipped to use architecture as a means of telling a story. Every building tells a story, of course, but not many are able to embody the narrative within their very structure. This is a rare quality, one that few architects can bring to their work.

But perhaps the reason starchitect status has eluded Safdie is that his buildings do not have a signature style. Though various motifs such as curves, concrete, and columns have preoccupied him at different times of his career, it isn’t easy for most people to identify a Safdie work the way it is with, say, Gehry, Daniel Libeskind, or Zaha Hadid. He takes his cues from the unique circumstances of each project, and as a result, each project is different. At the opposite end of the continuum is an architect like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, whose every building looks nearly identical regardless of its purpose or location. But as Safdie observes, “Mies’s architecture was about a single idea—he imposed it recklessly regardless of programmatic considerations.” Safdie, on the other hand, allows himself to be a “chameleon”.

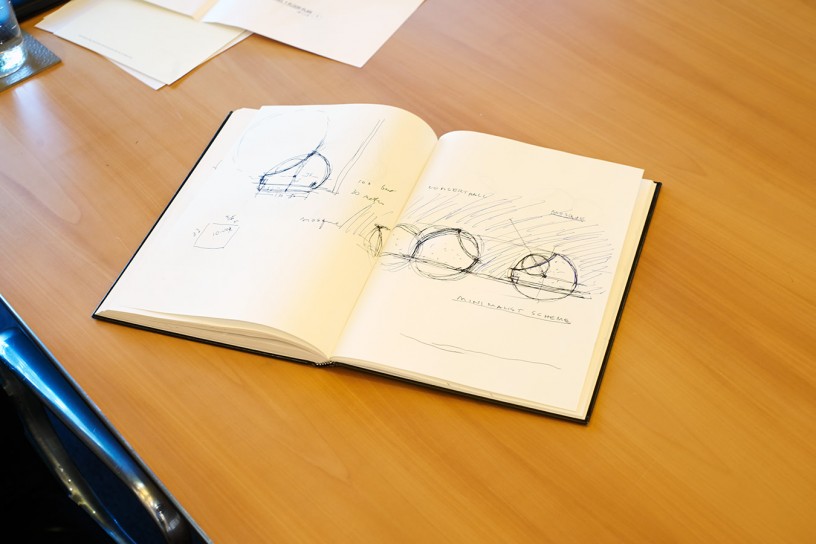

“Every building starts with a sketch,” he explains. “Almost simultaneously, we start making models. But we make models of the whole site, complete with all the other buildings around it. After that, we start putting stuff into the computer. Sometimes we start from the inside. Sometimes we start from the outside. It depends.” (A showcase of past sketches and models, along with films and photographs from the architect’s near 50-year-long career, will be on display as part of Global Citizen: The Architecture of Moshe Safdie, an exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles until March 2, 2014.)

Wandering around Safdie’s office in Somerville, it’s easy to see what this means. His staff of almost 100 sit at computer screens or are gathered in small groups; Safdie moves among them comfortably. He is personally involved in every commission and can speak knowledgeably about its every detail. Because he has offices in Somerville, Singapore, Shanghai, Toronto, and Jerusalem, Safdie spends countless hours jetting around the planet.

“There are four places I consider my hometown,” Safdie says. “Haifa, where I was born; Jerusalem, where I have spent much time; Montreal, where I still have family; and Cambridge, where I live and work. I have three passports: American, Canadian, and Israeli. I feel very Canadian. I feel very Israeli. I’m starting to feel American, but not in the same way I feel Canadian. My family left Israel because my father was disgusted with the Socialist politics of the 1950s. My mother wanted to live in an English-speaking democracy. So we moved to Montreal.”

While living in Israel, Safdie originally intended to study agriculture, work on a kibbutz, and help establish the fledgling nation. But once in Canada, the intention to pursue agriculture no longer made sense. After taking an aptitude test in high school, he was told he’d make a good architect. The rest, as they say, is history.

“We’re at the beginning of a period of great change,” Safdie argues. “Naturally, there’s a lot of resistance. Buildings and cities changed because of the automobile, but mobility is still a way of lifestyle and where you live and work. Village life is not coming back. The metropolis is the foundation of modern life. Densities in Asia are staggering. When I did Habitat, I had no idea what densities would become.”

In Cambridge, where Safdie lives in a 250-year-old house in the heart of the Harvard campus, any talk of density seems academic. Safdie’s Somerville office studio, in a beautifully restored red-brick wicker furniture factory, is in the middle of a gentrified neighbourhood whose streets are lined with pleasant houses and mature trees. Sitting in his large, light-filled office, surrounded by the mementos of a long and distinguished career, Safdie presides over a practice that, like North America, is made up of people who have come from around the world looking for opportunity. At the age of 75, he has not only seen enormous changes but also played a role in making them happen.

Much is different, and for this architect, the world has never been smaller, opportunity never greater. But some things never change. Moshe Safdie still has his notebook in hand, and a pen at the ready.

For more information&visuals,please visit

> via NuvoMagazine