Submitted by Tarun Bhasin

A Pulse in the Nebula

India Architecture News - Jul 15, 2019 - 23:33 13503 views

In 1973, NASA launched Skylab, an unmanned space station to the earth’s orbit. It was met by 3 crews of 3 members each over a period of 24 weeks for data gathering. Its decaying orbit meant that NASA needed to bring it back to Earth. They assumed that in the 8 years it was supposed to be in orbit, they will be able to develop the technology that would bring Skylab back. They couldn’t. And in 1979, Skylab came crashing down into the Indian Ocean and Myanmar.

Image courtesy of NASA

Act I

India has for long been a case study of urbanization, even before Independence. Being the most industrious colony under the British Raj, India was quickly churning out resources and finished goods with its surplus of labour found in key urban centers staggered all over the country. From 1901 to 1951, India’s urban population grew from 25.8 million to 62.4 million. Therefore, after Independence, the government was quick in recognizing the need for adequate infrastructure in the cities. But, within this rural-to-urban migration lay a trend that would come to demand a completely different outlook for infrastructure that will not be made possible till the next century.

Most of the people migrating from villages to towns and cities to work in textile mills, construction and trading were seasonal farm labourers. This meant that these people were working in farms for the production of Kharif crops and then moving to cities in search for casual work, mostly in textile and trading, for the rest of the year. Most of these labourers worked for daily sustenance, and since they had to pay for travel, accommodation, and facilities by themselves, it left them with no savings or assets at the end of each cycle, making them vulnerable to economic downturn and exploitation at the hands of some contractors and civil authorities. Noticing the gap, the Government of India was quick in recognizing a model policy that came into effect to delineate the conduct of industries with migrant workers – The Inter-State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act 1979.

The Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act was intelligent in recognizing the components of barter between the employers and informal workers. It was primarily based around provisioning measures to regulate and normalize income, labour, and capital for any system or set-up demanding work from more than 10 workers. The Act set up norms to define minimum wage and working hours for casual work across the country and different sectors of the industry. Further, realizing that movement between rural and urban areas was a major component of expenditure for informal workers, and a critical component for the availability of labour, The Act mandated provisioning of displacement allowance within the tenure of work and journey allowance at the end of the tenure of work.

The policy further went ahead in an effort to create social equity, by creating norms based on regular pay and equal pay irrespective of sex. On paper, considering The Act was passed in the late 1970s, it was a significant achievement to have furthered the notions of gender parity in the workplace. This notion was further strengthened by provisioning suitable workplace conditions for both the sexes. The policy measures mandated the employers to provide free of charge adequate residential accommodation, medical facilities, protective clothing, drinking water facilities, water closets, washing facilities, creches, canteens, day-care units, and healthcare units. This marked a significant effort in delineating the flow of capital expenditure in creating income-producing assets/ventures.

The policy affixed the idea that an employer had to use the capital not just to create infrastructure that will be utilized in the production of goods, but a portion of the capital must be set aside to create industry infrastructure that would enhance the quality of life of workers that provide their labour for utilization of industry infrastructure to ultimately produce the goods of value, thereby, asserting on the importance to maintain and enhance social capital in the section of the society that remained economically marginalized, deprived of assets and socio-cultural growth. The Act also set up a committee that would oversee the implementation of these policies. On the ground, it set up the liabilities of the employers and contractors and made it mandatory to select a representative as an intermediary between the business and the local government body.

Image courtesy of swaniti.com

One would think, that the Act being as expansive as it was in advocating the right to adequate infrastructure for the migrant workmen, would be a catalyst in changing the nature of the industry, but then, one would only be speculating. Having a need does not always mean that there is a product to fulfill that need. Even though a great part of the industry, especially the textile industry was quick in implementing most of the provisions mandated by the Act, its adoption in the Indian Real Estate landscape was laughable. While it was easy for industries like Textile and Trading to set up static infrastructure near the places of work in the form on Chawls and Aanganwadis, it was however nonviable for the real estate industry to do it, for the changing location of work every couple of years. The idea of providing static infrastructure to a huge population of workmen for every project, made available by pooling land from part of the project or leasing from government, only to demolish it at the end of the project and do it all over again, is illogical to any resource-intensive industry. It simply means bad business. And while other industries could leverage the policy and create housing facilities, however inadequate, they had to do it only once unlike the real estate. Thus, the lack of possibility resulting from incompetent building materials and construction techniques, and design methodology, became a widely accepted excuse in the real estate landscape for blatant flouting and conflagration of the Act.

Quickly, following a confrontation with the issues related to its execution, on-ground implementation faltered with selective adoption of measures, the whitewashing of liabilities and responsibilities undertaken by some employers and some contractors, and eventual dilution of the larger meaning of the Act itself. It became an attitude amongst the industries that the values of social capital suggested before weren’t intrinsic to the idea of nation-building but only idealistic sentiments purported by the government. Thus, in the absence of a larger infrastructure of materials, of technology, of design thinking, and of business strategy; a well-intentioned plan, futuristic and progressive in its approach, quickly deviated from its intentioned orbit only to move towards a path of quick obsolescence. Like the Skylab, in the face of lack of technology to keep it in orbit or to safely land it home, the Act also came crashing down fragmenting into smithereens of its values it aimed to transfer to the industries.

Image courtesy of Hatch Workshop

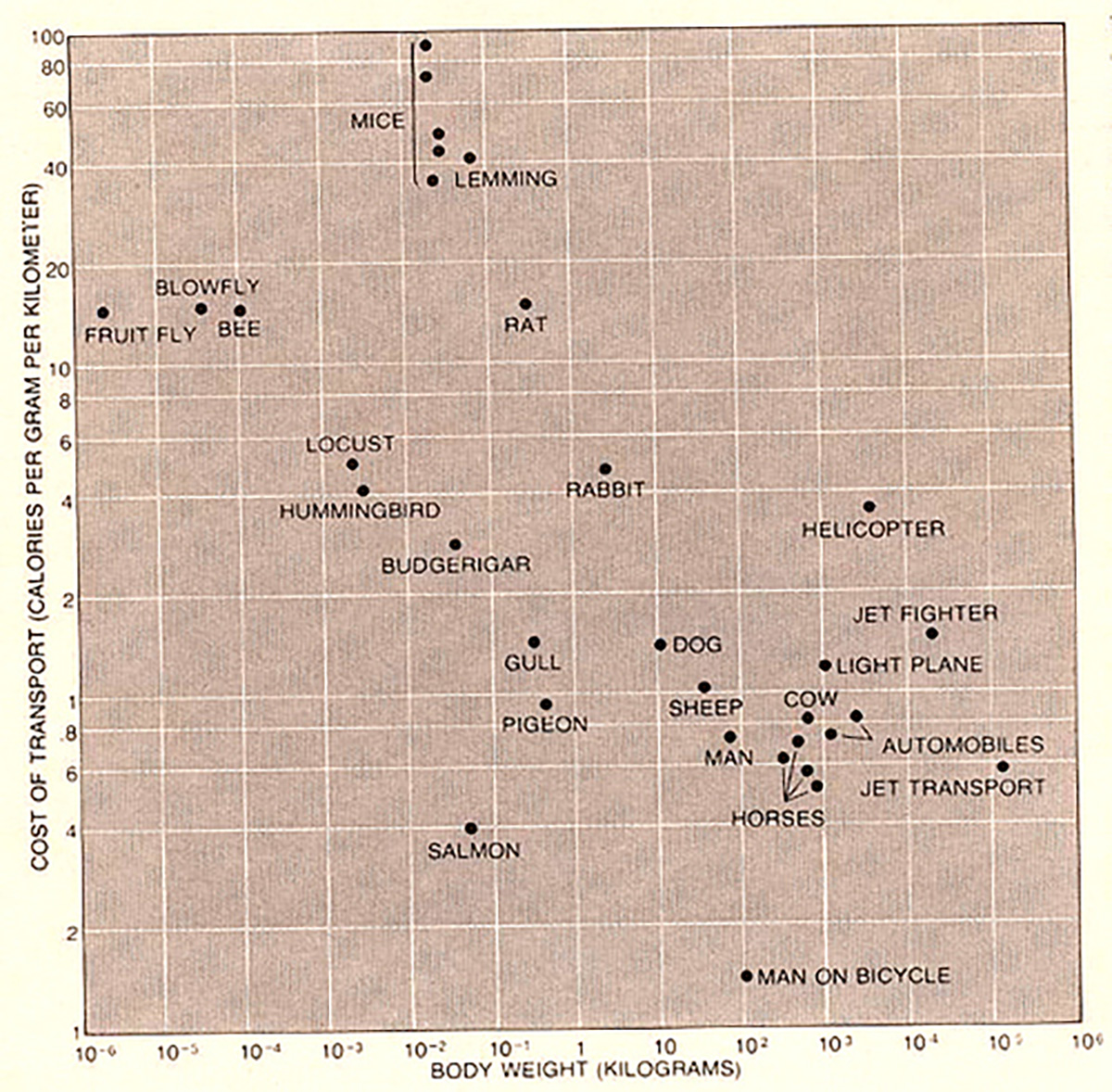

A chart from Scientific American in 1973 shows a graph, originally compiled by Vance A. Tucker of Duke University, which marks the relationship of cost of transport (calories per gram per kilometer) to the bodyweight of species (in kilograms). Although, several species of animals and birds vastly outperform humans, a man on a bicycle ranks first in efficiency among traveling animals and machines in terms of energy consumption, outperforming the condor, automobiles and jet transport. It reveals that in evolutionary terms what wins is not the surplus of energy or the most exclusive technology, but the simplest tool powerful enough to emancipate the masses.

Image courtesy of Scientific American

Act II

In the two decades that followed the creation of The Act, urban centers in India grew multifold. The National Commission on Urbanisation in 1988, published voluminous reports on the urbanization trends revealing more than 100 centers throughout the country, that were mostly hubs of textile, retail, consumer goods manufacturing, trading, services and IT-BPO/BPM. In the meantime, employment under agriculture and its share of contribution to the country’s GDP deteriorated. This further propelled the country to rely on the development of its urban centers leading to an exponential growth in rural-to-urban migration. International competition, liberalization of economy and automation in the manufacturing sector led to slow absorption and growth, in turn, driving down demand for labour. This coupled with the demand for new real estate for the ever-increasing and expansive towns and cities, boosted absorption of surplus labour by the Real Estate industry making it the 3rd largest employer in the country.

But, the failure of The Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act in the real estate meant that while other industries in the meantime had produced enough social capital for mainstreaming of its labour into the socio-cultural fabric of cities, real estate had largely absolved itself from the issue, shying away from the possible need to the extent of denial amongst the employers, and contempt at the hands of some contractors. The construction labourers of the country, some 14.6 million in 2001 were an unregulated floating population, travelling from one state to another in search of daily wage work. 93% of the total workforce of the construction industry was comprised of informal labourers with little to no skills and high attrition rate. It soon became evident that the cogs of the bullock cart were wearing out in the age of automobiles, and if nothing would be done to help the real estate organize and legitimize its infantry, and if they were continued to run directionless, it would lead to social collisions in urban areas and implosions within the industry in the coming days and age of global economy leading to eventual decay of the industry itself.

Recognizing that now the legitimization of labour in India meant, foremost, the labour in the construction industry, almost two decades after the first act, the Government of India rolled out The Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1996. While the BOCW Act borrowed most of the concepts from its expansive predecessor, it dawned upon the recent developments in the nature of work delineated on ground due to contentious practices by some contractors, who forced workers to undertake long working hours without breaks, irregular payment systems, unsafe workplace conditions, lack of holidays, lack of day-care breaks for women with children and much much more. Any NGO working in the sector would easily tell that the conditions of construction workers in comparison to other workers in the country was abysmal and alienating while comparing it to human rights standards, they were almost apocalyptic.

The Act aptly provisioned a minimum of one break every day and one paid holiday in a week for all labourers, along with wages for overtime work. It took from the previous Act, to include the mandatory provision of drinking water, latrines, and urinals, free of charge accommodation within or near the worksite, cooking places for families and individuals, bathing, washing, and lavatory facilities. But the biggest intervention of The BOCW Act was the creation of a Cess fund under The Building and Other Construction Worker Welfare Cess Act 1996 that required all developers to pay 1% of the total construction cost to the government as part of the labour tax that will be utilized by the government in social development of construction labourers. The developers were supposed to register their workers under the act and pay the tax, the states were supposed to collect it and the center was supposed to regulate it by further reimbursing the amount to the states. It created another problem. Since, most of the construction workers being migrants are not present in their states to avail the benefits, the funds lay idle since the respective states were not willing to spend money on migrant workers; and the lack of identification of labourers on-site and the high frequency of movement from one employer to another led to a blockade of any possible action.

Image courtesy of Hatch Workshop

Despite the lack of direction to the Cess fund, the BOCW act saw a lukewarm, yet in comparison to its predecessor a successful adoption, by the real estate industry with 21 million labourers registered as beneficiaries through developers. It was largely successful in changing the mindset of the developers to once more think about the development of social capital of their own community, largely aided by technological developments that were just-in-time to make social infrastructure possible. Work started again. Over the next 23 years, a total of INR 45,473 crores was collected, out of which INR 17,591 crore was spent by key states, by liquidation into consumer goods such as utensils and electronics disbursed to construction workers, mostly as part of election propaganda. As of 2019, a total of over INR 28,000 crore lies in the government treasury waiting to be utilized.

Here, the Cess fund can be likened to the amount of energy (calories) of the species, where the race of evolution is not determined by the surplus, but by the tools that make the expenditure of that energy, efficient and viable over time. The BOCW Act, despite its failure to put into action this surplus, or provide the tool that would emancipate the species, did in fact hint towards the future development of the tools that would prove keystone in the sector. It reinstated the employer’s responsibility to work upon and provide capital expenditure for the facilities but with the addition of one understated revolutionary word – ‘temporary’. The Act emphasized on the provision of temporary structures as facilities that were to be simply removed/demolished or dismantled from the project site or adjacent land leased from the government. With the adoption of steel and corrugated iron sheets in smaller constructions and informal housing, it had become viable for the market to put up sheds to facilitate sheltering of workers. Thus, a small nudge through the policy and relaxation of bye-laws opened up options for further design explorations and creation of the right tool.

Image courtesy of Hatch Workshop

In 1997, Steve Jobs as the CEO of NeXT computers developed one of the most famous personal computers of its time designed for college students, who were in search of a versatile yet affordable personal computing option. The lack of development of cheap hardware in the industry meant that the computer developed by NeXT would not be affordable, and a lack of indigenous Operating System meant that the computer would not be functional at all. But the value of the computer lay not in its finality as a product but its design definition, which was recognized by Apple Inc. that was in dire need of design innovation and ready to supplement the hardware with its perfect OS. This led to rehiring of Steve Jobs as Apple’s CEO and roll out of the most successful personal computer chain with end-to-end design and operation solutions – the Macintosh, making personal affordable computing popular, spearheading market development of computer electronics and driving incremental costs down.

Image courtesy of Apple Inc., cultofmac.com

Act III

Before we come to the present, it is important to look at the developments since the introduction of The BOCW Act in 1996 that further shaped the landscape of the Real Estate and led to the creation of an ecosystem conducive enough for the right tool to be put into action. The first and the most crucial obstacle in putting any tool into action were local identification and service entitlement of labourers that could keep pace with the attrition rates and frequency of their movement. Since it meant that labourers were largely unregulated, and thus, untracked, services could not reach them in the age of paper. The digital revolution changed that. With companies and government both moving to data science and ICTs with advancements in internet and telecommunication, it has become virtually possible to track movement and deploy services throughout the country with effective monitoring, accounting, and auditing. The most recent step by the government is the rollout of Aadhaar, which although controversial, has proven to be the bedrock to link local and national identification, spearheading cloud-based service systems. Furthermore, improvement in communication and transportation technology has lowered search and transaction costs and eliminated labour intermediaries.

The second obstacle for which the Cess fund was sought to be deployed was the strengthening of occupational health and activity and facilitating grievance redressal. Although there is much apprehension on the role of contractors in the system, their existence as intermediaries is particularly useful in providing to the labourers a smooth income over lean periods, short-term ad-hoc loans and risk covers; and the role of developers in undertaking new technological research and development and consequent skill training of labourers is another fundamental aspect of the evolution of this ecosystem. This was taken care of by The Companies Act 2013 that lay down the legal and ethical obligations of companies and their intermediaries, created a Corporate-Social Responsibility (CSR) fund for skill development of impoverished sections of the society, and strengthened labour laws; the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016, (RERA) that propelled and consolidated the concept of time-management in the real estate, requiring further legitimization of workforce and their skill development due to adoption of better construction technologies and methodologies; and finally The Central Goods and Service Tax Act, 2017 (GST) that brought the businesses under a singular tax framework that would allow the integration of extra-corporal activities as intrinsic business models.

The third crucial aspect was the change of mindset in design and programme based real-estate models. Real-Estate till 2014 was largely involved in processes and development of design programmes that served the Indian upper class and middle class – largely, the consumer class. But, with the push for affordable housing and Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), the real estate since 2014 ushered into an era of socially responsive architecture leading to the refreshment of its concepts and outlook towards its supply-chains and economies of scale. Low-cost, merged with sustainability, merged with income-producing assets and livelihood development of inhabitants, has given way to demand of not just sale-purchase assets but also rent-based assets. Therefore, the third obstacle paved the way for an underlying theme for the development of the tool that would ultimately utilize the Cess fund.

And now coming to present, in one sweep, the central government hit the nail right on its head by rolling out the draft National Urban Policy Framework 2019 that in two simple lines declared – "It is imperative to move beyond the family-based housing unit towards communal and flexible modes suited to, for example, migrant workers" and "Labour cess should be utilized for providing rental housing for the construction workers." In a stroke, the government has opened the market to allow developers to create business models that deploy temporary shelters and community infrastructure for construction workers that are affordable and can be rented out over a 10-year or a 20-year lifecycle, minimizing the operational expenditure on behalf of developers and further creating economies of scale by lowering incremental costs. To conclude, developments since 1979 have come to a point where for the first time it is viable for the developers to openly embrace the development of social capital amongst construction workers in lieu of increased productivity and human potential over a period of time.

Image courtesy of Hatch Workshop

Although The BOCW Act, had hinted towards the development of temporary shelters, the design industry particularly, with its focus on more commercial and less-social processes was in-line with standard recommendations and ideas; and for a long time developers were left on their own to develop solutions without the help from architects. This is self-evidential looking at large developers such as Larsen and Toubro, and Tata Housing, which resorted to launching their own pilot projects of developing temporary shelters for migrant construction workers due to the lack of availability of solutions from third-parties. But an individual shelter is not the project scope here, it is the design of a community infrastructure that includes all the facilities stated in the above two Acts that can be further dismantled, transported and rearranged in perfect order while accounting for and being able to service individuals and families both. This requires running capital and operational costs which make it unviable to provide quality solutions free of cost, leading to a situation for developers to put in incremental costs with every project and thus, left demanding for affordable rent-based models.

It has come to the point where design and process excellence has developed independently on one hand, while operational and management capacity has developed independently on the other, with players of both the sides waiting to find their perfect suiter. Like Steve Jobs’ design and Apple’s OS, that created the perfect value-driven consumer PC market, Real Estate in India is looking for an amalgamation of a perfect design-based approach for temporary community shelters and business strategy for social development management to churn out a tool that will revolutionize the lives of its stakeholders and become the bicycle of the existing surplus of Cess fund. Enter the protagonists of this story, Nebula Infraspace LLP and Hatch Workshop.

Image courtesy of galloper.com

As of 2018, the construction industry contributed 8% to the country’s GDP employing 10% of the total workforce, making it the 2nd largest employer in the country. Out of this 10%, 93% of the total workforce was informal, out of which, over 50% were migrants spread out throughout the country. A whole nexus of individuals moving in an almost orchestrated manner, like dust particles that compose a nebula, forming a grand magnificent overwhelming image from afar, but liken to vacuum of endless empty space when one ventures in it. Nebulas are the birthplaces of stars, and in 2018, the nebula of migrant construction workers in India breathed out its first pulse. A star took shape.

Image courtesy of galloper.com

Nebula Infraspace LLP

It is least surprising and more heart-warming that the initiative to work on a housing model for migrant construction workers was taken by a real estate developer that came to existence with a vision of providing 10000 affordable homes by the year 2020. Nebula Infraspace LLP came into definition in the year 2016 with an aim to provide affordable housing models during a pulsating yet unconsolidated housing market. With its inception, it launched two projects under the flagship name ‘Aavaas’ that means ‘an abode’, one in Changodar (on the outskirts of Ahmedabad), the other in Hyderabad, and one more recently in Chennai.

Being in the affordable housing market that treads on a thin profit-loss line relying on perfect balancing and execution between design, project management, and ticket price; and being a company compliant to RERA; Nebula understood that it was crucial that all the cogs of the vehicle were moving smoothly. But they soon realized that the unprecedented informalization in the industry was impacting their productivity and organizational health, driving down the performance of their projects. “We have to put in a lot of effort in the skill training of a labourer, and if he/she leaves the project after that training, or is unable to work due to poor health or social conditions, it impacts the value of the project significantly. Since the rate of this churn was high, as much as 80% with some other developers that we talked to, we knew this factor was hurting us the most,” explained Mr. Sameer Gandotra, Director of Nebula Infraspace LLP and the man responsible for envisioning the pilot project.

Naturally, the company started thinking on possible methodologies that could be implemented in consensus with the civil society to increase the productivity of its labourers and reduce their attrition rate. They sought out, looking for empirical research on service recommendations that could be adopted, or experience from other parties that could add to the company’s learning curve, but they couldn’t find any. They understood that there were many NGOs working on individual factors to help the migrant construction worker community, but an integrated and elaborate approach to doing things was missing. This was causing a loss on both sides. A model to supplement change in the right direction that was needed was missing. On observing that, the company took the initiative of running a pilot project to see if a model could be created out of it.

They quickly recognized four social development factors that would provide the foundations of this integrated model – Public Health, Sanitation and Hygiene, Nutrition, and Education. The company in its research found the key problems that were ailing the labourers and disabling them. One of the major reasons was poor health. The community suffered from a high rate of communicable diseases such as Tuberculosis and AIDS, which needed to be treated with primary and secondary healthcare measures; further aggravated by seasonal diseases such as Malaria and Cholera as a factor of living in an unhealthy environment and drinking unsafe water. Further, the construction workers suffered from chronic ailments such as Arthritis and Anemia (especially women), due to lack of both macros, and especially, micronutrients in their diet. Since most of the migrant workers were unaware about the healthcare systems in the context, and the inability to speak the local language added to their plight and they either shied away from opting for healthcare or ended up overspending. Lastly, their frequent movement resulted in a lack of formal schooling for their children or their own professional skill development, hampering any future growth prospects as well.

Photo courtesy of AVPN Asia

With the foundational trends in place, the company quickly envisioned a model on three primary provisions – User development, spatial conditions, and Soft Issues – partnering with Aajeevika Bureau, an NGO that specializes in tackling broad social and development issues by organizing workshops for migrant workers; AMRIT clinic for providing healthcare facilities, medication, and regular check-ups; and SAATH Charitable Trust for running a creche to educate children in a friendly environment; and The 4th Wheel for social education (such as personal hygiene and sex education) of labourers, especially women, with evening classes. Furthermore, the company took charge of running a meal programme providing nutritious mid-day meal for construction workers and their children to fulfill their daily calorific values supplemented by vitamin tablets to maintain their vitamin and mineral intake.

With the model of the programme in place, taking care of user development and soft issues, the company went on to delineate micro aspects that were needed for proper functioning of spatial environment. Use of adequate firefighting system, bio-digester loo systems, stoves and gas cylinders, solar panels, waste composting, planters, sewage treatment and drinking water facilities, were charted out and added to the list. “We had to go into excruciating detail in realizing the project. One part of it was managing the entire programme in collaboration with many different stakeholders, and the other aspect was the need to visualize the on-ground situation to the minutest detail of selecting and placing fire extinguishers and food compost bins. It was an extremely difficult and painful process, and at times we were left thinking whether our own identity as a real estate developer and our commitment to realizing on-going projects should allow us to take liberties and do something as extensive as this project. But, we knew it was imperative to do it, and all the partners in the firm were in consensus that we had to atleast try, regardless of a significant outcome,” says Mr. Sameer Gandotra shedding light on the existential dilemmas any developer would face, if they ever ran a similar pilot project of their own.

With the persistence and ingenuity of Nebula’s CSR department the company consolidated the operations of the project under their CSR fund, covering over 400 workers at Aavaas Chandogar site in its first phase. This left them in need of only one thing, a design blueprint for the spatial conditions of the temporary housing, that would not only adhere to the financial and project management restrictions under the CSR programme, but act as a catalyst in community growth, social interactions and memory. Here, architectural design became the keystone in realizing the diverse social functions and events, putting the necessity of intelligent spatial logic at the heart of possible operational success and future proliferation of this entrepreneurial effort.

Image courtesy of Hatch Workshop

According to National Sample Survey 2007-08, 60% of the total migrant construction worker population comprises of families with both working adults and one or two children, another 12% of families without children, another 5% comprising of single parents with children, and another 1% of non-working elderly with children. Together they comprise 22% of the total construction force, relying on a sanguine social environment, holding together the fragile social fabric of the whole community on site. Housing in such a context is not there to only support the practical conditions demanded by an abode, but it ought to ensure the safety and security of women and children as its primary concern, to create and forward a tool that can allow for sustainable development to happen.

Image courtesy of AVPN Asia

Hatch Workshop

The other significant partners to this program are Hannah Broatch and Mason Rattray of Hatch Workshop, New Zealand. Hannah Broatch was studying in CEPT, Ahmedabad when she started looking at informal settlements on the side of roads and informal housing setups on encroached spaces. These were spaces marked by makeshift tents made from plastic sheets, brick, bamboo, and rustic galvanized iron sheets. She delved into the social interactions of these spaces, trying to find the entrepreneurial mindset behind their design and planning.

She found the resultant spaces deeply innovative and productive but highly susceptible to dysfunction resultant from a lack of any basic social or community infrastructure. Recognizing that the root of the problem in poor housing condition lied in social, cultural and political issues, such as corruption, exploitation, caste discrimination, undefined sites, and user groups, and substandard materials, she went on to explore the potential of architecture to work out these externalities to the design process to achieve a minimal standard of dignity for workers.

Consequently, she went on to design the blueprint for a temporary housing system that could accommodate 280 workers and their families, transgressing the commonly accepted norms and limits of architecture, that won her one of the eight prizes at the 2017 Hunter Douglas Archiprix Awards. After graduation, Hannah Broatch and her partner, Mason Rattray approached Nebula Infraspace LLP on the possibility of providing temporary shelters and community infrastructure to the on-site migrant workers, thereby, bringing together all the pieces of the project together. The architects worked closely with Nebula Infraspace LLP and the migrant workers on site, to critically assess design possibility, develop the process of construction and maintenance that could be replicated without the dependence on architects, and maintained without much effort from behalf of the company.

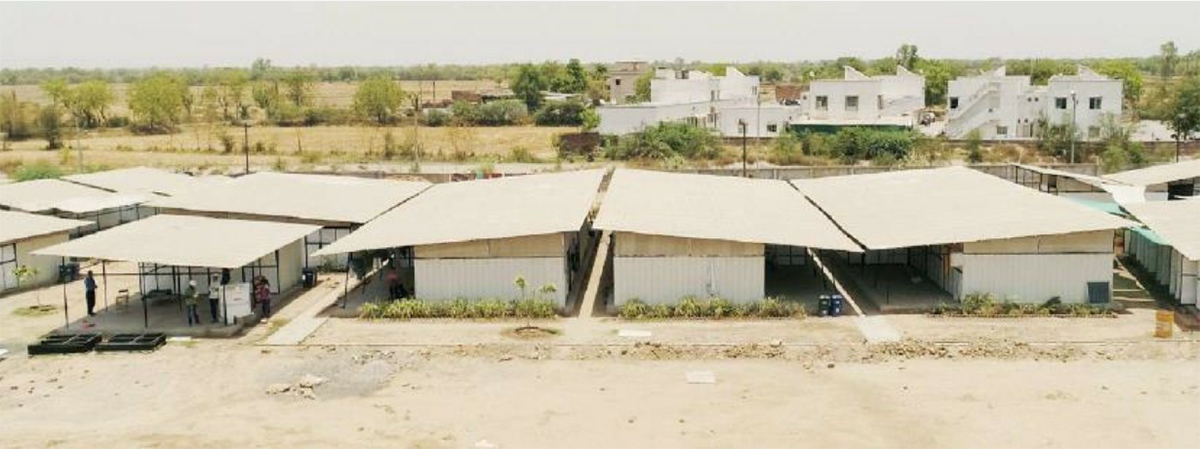

Video courtesy of Archiprix International

Today, the site of Migrant Construction Worker Housing at Aavaas Chandogar, is a sunlit breezy site. Walking through the uneven construction landscape of the housing project towards the worker’s housing, one notices the smoothness and evenness of the ground as one approaches the site. The surface has been flattened and evenly sloped to provide for adequate drainage and rainwater harvesting, that is directed through continuous gullies that cleanly divert the water away from the site, avoiding any retention and contamination. The land is dry and marked by evenly distributed planters that line the pathways, houses and community spaces, further helping in surface water absorption and necessary psychological upliftment in the middle of a construction landscape.

The network of lanes wraps the housing blocks, that are raised on a plinth. The housing blocks form a grid of 3x3m and 3x6m, conforming to the availability of steel in the market to add durability and adaptability to the design. The walls and roof are made of high-quality galvanized iron sheets supplemented by louvers for necessary insulation, with gaps below the roof to allow adequate air-flow to cool the structure and provide cross-ventilation. The gaps are protected with mesh and nets to protect indoor spaces from insects and mosquitoes. The placement of the sheds promotes self-shading of structures, thereby bringing down the ambient temperature in the hot and dry climate and making the environment breezy. While clusters of sheds are provided with shaded open space that is used to sit out and interact, put clothes for drying and allow the women to cook together in the evening; the wet functions are separated from the structures to maintain quality of sanitation and hygiene. The housing units mark the area at the core, with bathing units offset to its left and toilets in the back, with necessary separation for the genders. The canteen and food storage area sits in front for easy access and maintenance, and the compost units sit further away from the clusters.

The genius of the site is the placement of creche that is towards the deepest end of the site, surrounded and protected by the housing units. The creche is perhaps the most vibrant space that is carefully defined with its own boundary. A low steel fence contains a garden and play area that define the entrance of the building, followed by a verandah and an operable façade. The inside spaces are well-lit marked by floor to ceiling windows on one side bringing in ample daylight. The school has furniture setups for daycare of toddlers, segregation for a kitchenette, primary and secondary schools. The whole atmosphere is contained within the protective boundaries and watchful eyes of the housing units, adding to the feeling of warmth, sense of belonging and memory, while gently completing the spatial programme of the site.

In the words of Hannah Broatch, "The design attempts to achieve a lot with very little, providing efficient incremental improvements by making use of architectural qualities that already exist in the labour colonies. Furthermore, it attempts to make an appropriate 'first step' in a process of extending the opportunities that the city affords to a population living on the city’s physical, social and economic margins."

The entire construction and the supporting infrastructure can be dismantled, transported to another site and re-installed with ease and minimal wastage. The only static component is the foundation of the housing units that make up roughly 20% of the total construction cost, making the whole design economic in the long-run. Its simplicity and landscape quality define an aesthetic sense, that coupled with its spatial planning interspersed with private and community spaces, compose a holistic and beautiful image of a dignified community shelter – that provides a return in the development of human potential, much more than the cost put into its making. The difference is evident and visible when the design is compared to the unplanned sheds of the leftover workers situated adjacent to the site, who are waiting for upliftment by the company in the next phase of the project.

Image courtesy of Hatch Workshop

In the last 3 years, Nebula Infraspace LLP has provided housing to 500 migrant workers, schooling and day-care to over 100 children, 25000 meals and 8000 hours of teaching, treatment of 118 tons of sewage, composting of 70 tons of waste and recycling of another 23 tons, 270 health clinic camps, training of 125 female workers to make sanitary pads, and use of gas to replace 525 tons of firewood – all under part of the CSR fund amounting to roughly 1% of the total profits. According to World Bank, for every $1 spent on building social capital gives a return of $6-7 in a decade. While Nebula is striving towards adoption of this model for all its workers and there is still time before they will be able to evaluate the returns gained from their efforts (higher productivity, low attrition, and high worker retention), the question remains - is there a possible tool confounded in this story that can serve as a larger business practice to emancipate one of the most marginalized communities in the country?

Image courtesy of galloper.com

The Tool

The Migrant Construction Worker’s Housing at Aavaas Chadogar points to the need and acceptance of entrepreneurial models that combine social development practices based around project management capacity, take-off, and delivery of socially inclusive spatial design and planning. This also opens up the possibility for architects to venture into larger management based models for intrinsic work-dwell communities that are based around the social performance and acceptance of architectural designs.

In its witty design and construction methodology, and social development programme, the project ‘Temporary Shelters for Migrant Construction Workers’ co-developed by Nebula Infraspace LLP and Hatch Workshop has successfully acted upon half of the Sustainable Development Goals stated by the UN-Habitat, namely – No Poverty (1) by providing construction workers with affordable housing and basic necessities; Zero Hunger (2) by ensuring children and workers are provided with daily nutritious meals; Good Health and Well-Being (3) by providing regular healthcare assessment; Quality Education (4) by streamlining students towards formal education through quality learning in creche; Clean Water and Sanitation (6) by providing bio-loo systems, clean drinking water and effective drainage; Decent Work and Economic Growth (8) by ensuring safe working conditions, and safe living conditions; Sustainable Cities and Communities (10) by providing the construction workers and their families with a sustainable livelihood and community integrated with its context; and Responsible Consumption and Production (12) by ensuring proper waste management and re-usable construction.

One thing is for sure; if the 20th century was about permanence in architecture, the 21st century is going to be about impermanence. The entire saga depicted above from the first Act in 1979 to the most recent developments in the sector, and parallel development of Migrant Construction Worker Housing at Aaavaas Chandogar, point to the fact that there is need and ample scope for development of models for temporary shelters and community infrastructure that can be tweaked and enacted for different climates, community strengths and preference of the employers. And as these initiatives gain strength and the market opens to provide for services and goods for such initiatives, the incremental costs are going to come down.

As the government is moving to the possibility of renting facilities out instead of providing them for free, it is opening the market in days of the startup boom in the country, to create for-profit models that provide the developers the necessary facilities under their CSR programme, and take care of operation and maintenance, provide key management consulting and financial investment plans (with the possibility of imbibing larger roles of contractors as well). The Real Estate is hinting to the future possibility of Proptech startups in the arena, that will propel the growth of Architecture and Real Estate towards its social obligations to utilize the most advanced forms of technology, design thinking, policy and planning, into providing the best practices, services and integrated networks to the most underserved communities that make up the very processes of the industry, thereby, actualizing a process of transformation within the industry.

Image courtesy of AVPN Asia

There are some looming questions, however. What happens to the Cess fund? Will the successful rollout of such business practices by developers mean that they can utilize the 1% tax on their own like CSR fund to provide shelter to their workers on an incremental basis? Or the government is going to utilize it on its own to create rental housing on government land in chosen areas? Or third-parties are going to come forward and bag tenders for the implementation of diverse models and designs in different areas?

No matter what the outcome of the Cess fund is, it is imperative to argue that the real estate is going through a process and a willful effort of legitimization of migrant construction workers, that is at the heart of formalizing of 93% of its workforce that has not been recognized for their labour till date. The Real Estate industry of India recognizes that in the age of automation, skilled labour is the most critical component of timely and quality delivery of projects, and regulating the current workforce of unskilled labourers and developing social capital amongst them in return for greater retention and productivity is the key to improving organizational capacity and health in the coming decades.

"As a real estate developer, we feel that it is our duty to help in the upliftment of our construction workers that are like our infantry. And not much has been done in this direction till now on a large scale. However, it is not the job or even in the management capacity of a developer to take control of the day-to-day functions that are required to realize this vision. And as a developer, I want to call on the young generation of the country who are looking for opportunities; that they can and must adopt this model as a business strategy and try to mainstream this practice. And I can assure them that at least a third of the developers out here will be eager to help them in the adoption of this initiative," exclaimed Mr. Sameer Gandotra addressing a diverse audience at a CSR event in Ahmedabad.

Nebula Infraspace LLP and Hatch Workshop are moving to the possibility of concretizing the strategies towards legitimization of their workforce by the year 2020, and they hope to be able to further study its benefits and forward credible research and insights into the functioning and cost-benefit analysis of their pilot programme to the world. And if their research shows, that the retention rate and productivity of their workforce has increased, it will be the very first successful project of its kind that will be nothing short of revolutionary considering the vast possibilities that might unfold consequently – that pulse in the nebula, which will mark the beginning of many solar systems!

Video courtesy of Nebula Infraspace LLP

Top photography courtesy of swarajyamag.com.