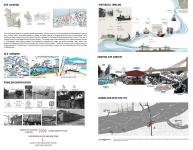

The project explores the intersection of tradition, sustainability and innovation aiming to preserve and provide a space to modernize an ancient traditional craft while empowering communities and fostering a deeper connection to Bangladesh’s riverine heritage with modern design, creating a space for boat makers, fishermen, locals, and tourists. Charpathorghata is a village in Patiya Upazila in Chittagong district relying on generational boat crafting as their source of income. The site is located on the bank of the Karnaphuli river. A part of the site is located under the karnaphuli bridge (Notun Bridge). The bridge spans the Karnaphuli river, which has been central to Chittagong’s boat-making legacy. This placement highlights the deep connection between craft, water, and modern development. Hence the site justifies the concept of the project.

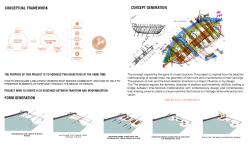

The purpose of this project is to address two objectives at the same time: “How to revitalize a relatively remote boat makers community and how to help to preserve elements of heritage through the means of design.” Project aims to create a co-existence between tradition and modernization. TRADITION MODERNITY

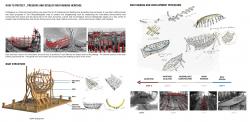

The concept draws inspiration from the intricate anatomy of traditional wooden boats, their ribbed spines, flowing hulls and hand-carved ornamentation. The architectural language is borrowed from this natural but precise geometry, adopting the rhythm and harmony of boat building as both functional craft and artwork.

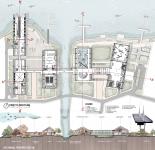

The design strategy of the "Crafting Centre" integrates craft, climate, and community in a cohesive architectural articulation. The form and function of the centre are derived from the internal logic and beauty of boat structures where every joinery, curvature, and voids are purposeful as well as poetic. Inspired by the structural harmony of a boat's spine and ribs, the project evolves as a progression of linear bays and semi-openings, allowing for programmatic and interactional flexibility. The elevated viewing bridge serves as the project's symbolic and spatial spine, connecting various functional zones—boat-making workshops, museum, riverfront promenade, market areas, and learning spaces—while also acting as a contemplative pathway over water and land. The unused area beneath the Notun Bridge is put to adaptive reuse converted into an area of net-repairing and informal selling zone where short-term or seasonal markets, craft stalls, and performances occur. By reusing unused infrastructural spaces as potential, the work resists unobtrusively the regimes between the formal and informal, past and present.

Biophilic design elements such as proximity to the river, inclusion of green enclaves, nature views, and tactility of materials are inspired in the design. These also reduce environmental footprints while fostering greater emotional and cultural connection to the riverine space. Community kitchens, resting rooms, medical clinics, and training rooms guarantee the boat-making community is well taken care of physically, economically, and socially. At its core, the design is not simply about the preservation of a craft, but about creating a regime of resilience by means of architecture that valorises identity, knowledge of craft, and the transformative role of place.

2024

In the design strategy of “Crafting Centre,” the rethinking of sustainable architecture has been linked with locally practiced “Traditional Boat-making crafts”. In this process, local adaptive method of vernacular architecture and available local material has been used enabling local artisans to actively participate in the building process, reinforcing a sense of ownership and continuity. The design integrates traditional craftsmanship with contemporary sustainability, honoring the ancestral wisdom of boat makers and related communities. In terms of sustainability, the design prioritizes using eco-friendly wooden materials and traditional building practices along with the steel joint ensuring that the construction and operation of the institute align with environmentally respectful principles. Engineered wood products like Glulam (Glued Laminated Timber) are introduced for major load-bearing elements, offering not only a low-carbon alternative to concrete and steel but also aligning with the regional context and craftsmanship. Glulam’s resilience and expressive quality make it particularly suitable for spaces inspired by boat hulls and skeletal frames. When compared to other construction systems, GLULAM has a NEAR-ZERO carbon footprint. It has been demonstrated to be a more durable and appropriate material in this context and cultural aspect. In designing the boat crafting centre, I essentially focused on the people who would use the space and their relationships with it. Passive design strategies are employed throughout: extended overhangs, wooden facades, and naturally ventilated roof profiles ensure thermal comfort while reducing mechanical load. The spatial configuration allows for natural daylighting and cross-ventilation, supporting the well-being of users, especially the boat craftsmen who spend long hours in the workshops. Research demonstrates that environments emphasizing human interaction can significantly enhance creativity and community engagement. By incorporating biophilic design principles such as communal crafting workshops, open collaboration spaces, and areas that provide visual and physical connections to the natural environment, the centre works as a cultural hub and can foster a spirit of collaboration and shared learning among artisans.

Author: Nazia Zaman

Studio Mentor: Sajal Chowdhury, Rezuana Soma

Thesis Supervisor: Sarah Binte Haque

Favorited 1 times