Submitted by

La Carboneria Housing Block Features A Dramatic Courtyard With Crossing Beams In Barcelona

teaser4-1--2--3--4--5--6--7--8--9--10--11--12--13--14--15--16--17--18--19--20--21--22--23--24--25--26--27--28--29--30--31--32--33--34--35--36--37--38-.jpg Architecture News - Jun 06, 2023 - 09:15 3602 views

Madrid-based architecture studio Office for Strategic Spaces has renovated a 19th-century housing block with a breathing and light-filled courtyard that is shaped by crossing beams in Barcelona, Spain.

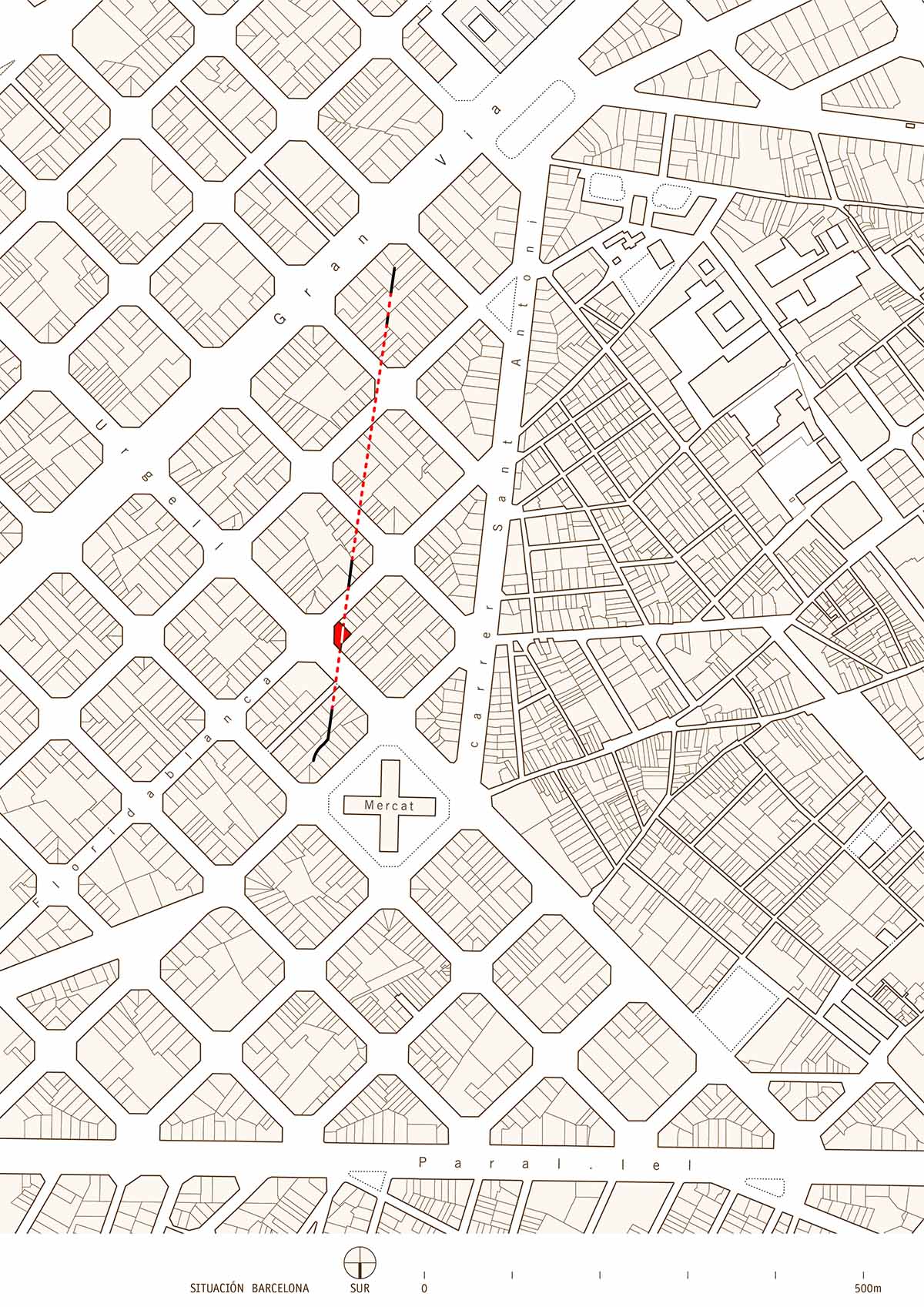

Named La Carboneria, the project, located in a humble 1860’s collective housing estate in Barcelona, is the oldest building of the seminal Cerda’s Eixample neighborhood, easy to identify by its iconic square urban grid.

The location of the project faced with major design decisions by the city to intervene with "long, wide and symmetrical axis and boulevards" which resembled the layouts of Paris, Vienna, Moscow or Washington in the middle of the 19th century.

Although some of the plans were shelved, La Carboneria was later faced with a "ghost façade" flanked by new buildings with an attached wall, forming a dark triangular courtyard behind it.

The Eixample, home to most of Gaudi’s works, is the XIXth century enlargement that paved the city’s way to an urban and architectural success that lasts up until today.

The recent rehabilitation of La Carboneria, completed by the Spanish architect Angel Borrego Cubero of Office for Strategic Spaces, brings to life a dramatic and thrilling history of conflict at the heart of the Eixample’s troubled beginnings, and makes it the center of gravity of the future life of the building.

Barcelona and The Eixample

The design of the new Barcelona of the XIXth century, the Eixample, was awarded by the Spanish Ministry of Public Works to Ildefons Cerdá, an accomplished architect, engineer and politician from Catalonia who had already been working on an in-depth study of the city in preparation for such a project.

Cerdá had designed a new type of ‘scientific’ and socially progressive city, with a smart mix of traffic and pedestrian ways organized in flexible and adaptable blocks.

The Town Hall, on the other hand, had claimed the right to design the future of its own city for themselves, and organized a professional competition to achieve it.

Unfortunately, the results of the competition reflected too faithfully the desire of the Town Hall to erect a more symbolic, rhetorical layout for the future capital of Catalonia, in the manner of Paris, Vienna, Moscow or Washington, with long, wide and symmetrical axis and boulevards.

Despite Cerdá’s plan having been chosen, the Town hall continued to push, institutionally and with bitter mass-media campaigns (newspapers, flyers), for the inclusion of larger boulevards and avenues in different areas of the city, something to which Cerdá consistently objected.

Through sheer luck, the edge of one such ghost avenue crossed exactly through the middle of La Carbonería’s land plot, which was crossed by the ‘Camino de Ronda’, the former ‘guard road’ outside the recently dismantled defensive walls.

The political battle lasted only a few years, but it was sufficient time to dramatically affect the original design of the building. In fact, the original promoter of the estate, Mr Tarragó, was forced to plan facades to all four sides of the building, at the moment radically unsure where the main streets would be and which ones his building would face!

Over a century and a half later, the facade that faced the never built boulevard, had to be recovered, its larger windows unblocked, even if they now overlooked two intersecting party-walls instead of Barcelona’s version of the Champs Elysées.

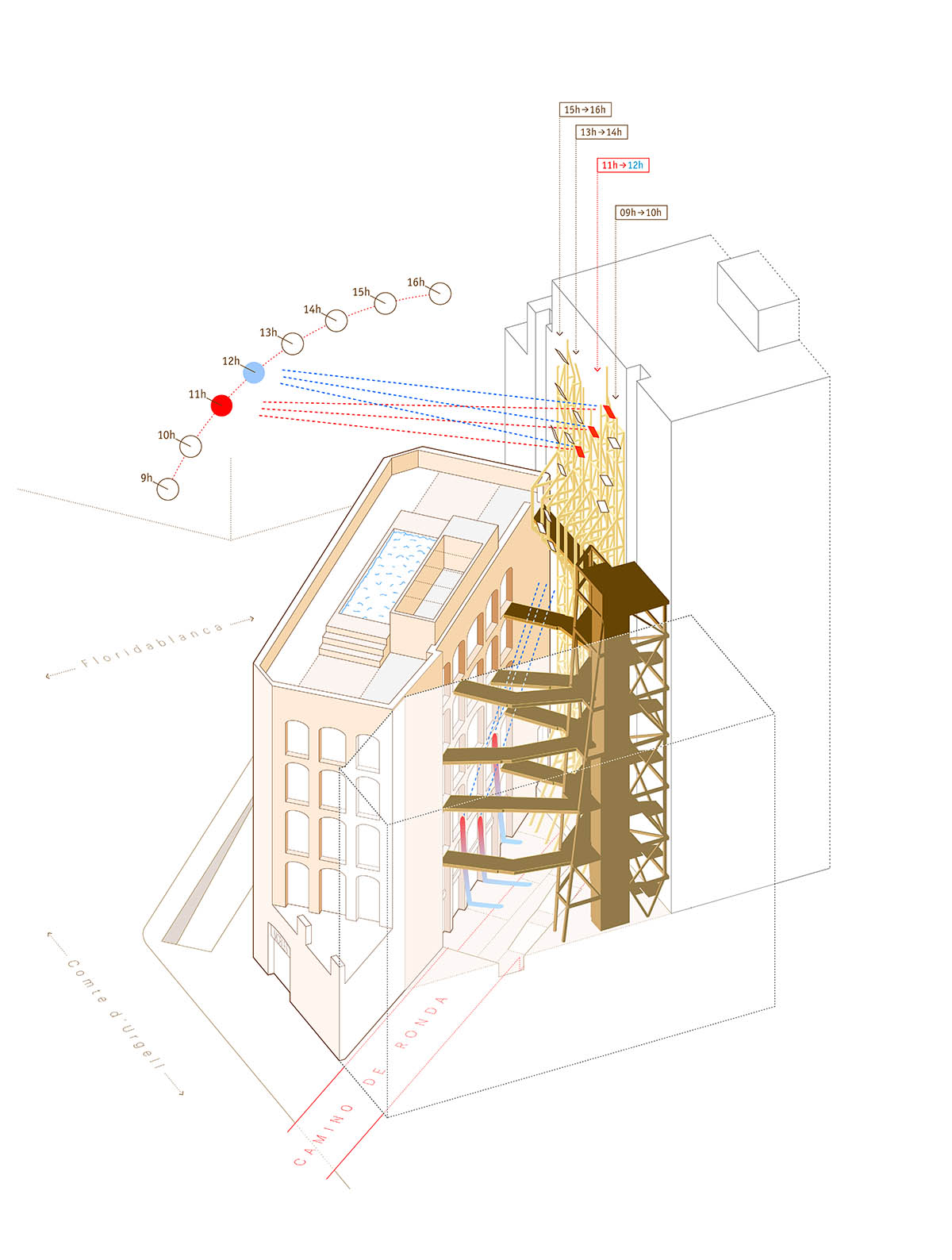

The architect moved the stair and elevator outside the building, to the opposite side of the guard road, making it possible for that facade to become part of the everyday life of the building and its visitors. The walkways that join both elements make the patio work as a surprising, tridimensional public space for the neighbours.

History as a resource for sustainability

In the pursuit of sustainability, the revaluation of history as well as past social and political conflict had a greater impact on the material qualities and performance of our design than the energy simulations we did with our sustainability expert.

"There is a material and energetic wealth embedded in the stories of any place that we must incorporate into our designs so that they are truly sustainable," said Ángel Borrego Cubero, the architect of La Carboneria's rehabilitation.

The original stairwell of the building had been demolished by its previous owner following the eviction in 2014 of the squatters that had occupied it since 2008.

Also, the Town Hall had catalogued the building recently, and, with this protection, it also imposed the obligation to recover the facade that was supposed to look to the never-built ghost boulevard, which however faced now two party walls meeting at a 90º angle barely ten meters away at its further point.

Placing the stairwell and elevator in this furthest corner allowed us to unite the desires and needs of the different actors in the process in a more valuable and sustainable solution for all: The facade that explained Barcelona’s enlargement project and its history has been made available for view from the stairwell and walkways and have become part of the local daily life; the small patio is now a tridimensional public space for the neighbours, a more interesting view from their larger windows than the original party walls; and one more apartment could fit in the space vacated by the old stairwell, which helped justify the more complex solution plus it has increased a much needed housing density in this desirable area of the city.

Details of the rehabilitation project

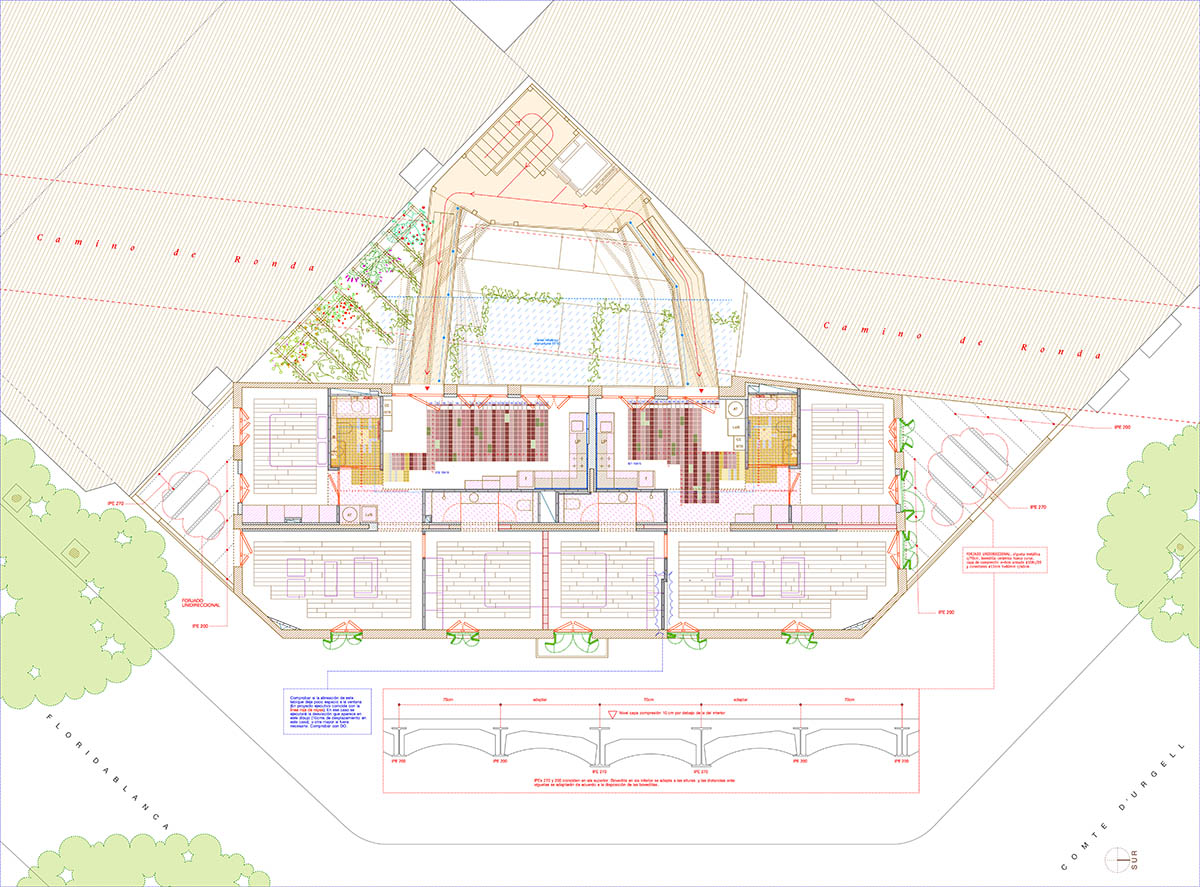

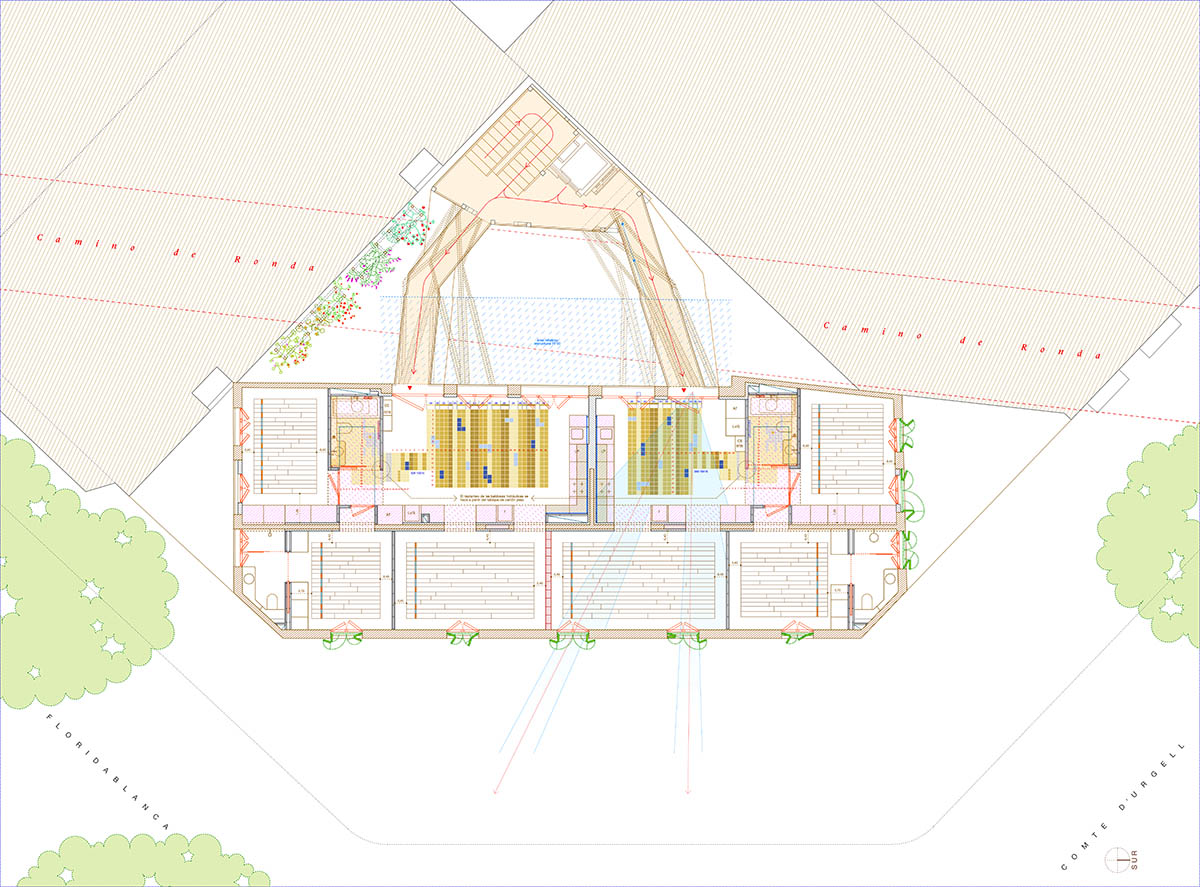

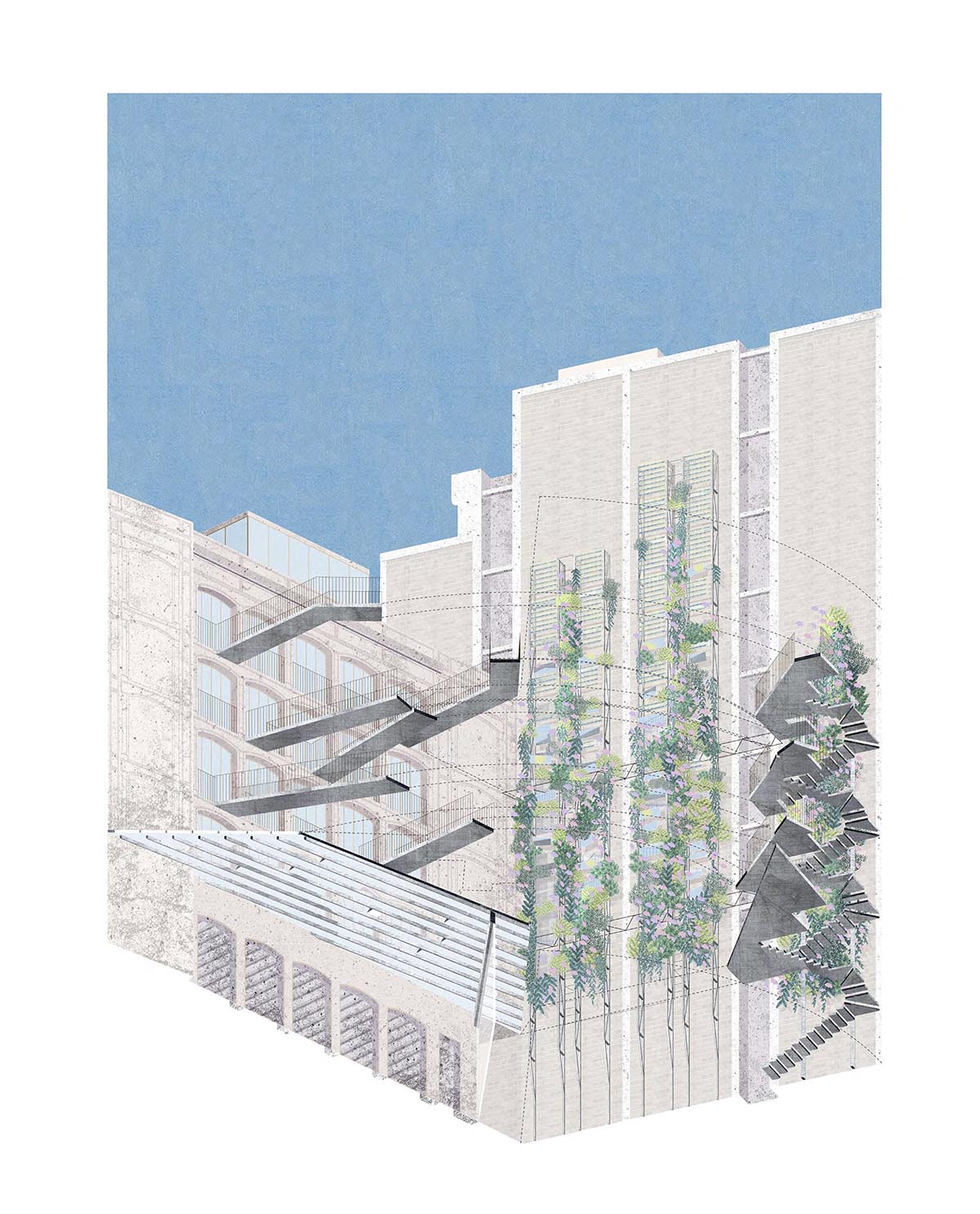

The building seems to have been turned inside out. Its most striking façade is hidden inside a triangular courtyard and, to make it accessible, its stairwell and elevator have been moved from the inside of the building to the furthest corner of this patio. The structural design of the communications core, the aerial walkways and the dividing wall seek to feed on this situation.

The large structure adjoining the party wall rests on the walkway that gives access to the roof, which acts as astabilizing horizontal beam. This allows the structure to grow taller and access the sun to bring energy and light down. Mirrors placed on it illuminate the lower floors’ apartments and the bottom of the narrow patio in the winter months. The structure is also prepared for the installation of a PV panel array and houses the planters.

The walkways with a bend are supported by crossing beams underneath. The support of their corners is not obvious at first glance, which confers the paths that reach the door of each home a weightless, surreal appearance. The lack of vertical struts or cables also allows for a greater freedom of design in such a constrained space.

Although the heritage regulations applicable allowed us to gut out the entire building except the facades, the original structure of the building was preserved as much as possible. In the end, only the roof needed replacement. The rest of the floors, walls and foundations were reinforced to the extent of the new needs and demands.

These reinforcement works were mandatory, but once completed, the surplus of available loads was used to make the roof accessible and place a 1m deep collective pool o top of the middle bearing wall.

The interior distribution of the apartments protects and emphasizes the original bearing wall that divides the building in two parallel spaces.

Storage and mechanical areas follow this middle wall, which becomes the most important element of the interior layout. Openings in this middle wall allow for the visual connection between the living areas of the home, the inner courtyard, and the street as conceived by Cerdà.

Other advantages of this solution are effective cross ventilation and natural lighting throughout the day, thus contributing to energy savings with passive solutions. Together with the use of original, breathable materials and other relatively natural finishes, such as waxed or oiled pine wood, a generous and free of volatile substances space is achieved.

Insulation of the roof alongside carpentry and glass designed to insulate thermally and acoustically from the busy Urgell street, allowed an average consumption of less than 60 per cent of the local average without adding insulation to the exterior facades, thus avoiding damaging the exterior of the building, subtract space inside, and other problems of the multilayer solutions less suitable for the Mediterranean climate.

"While responding to current needs and regulations, this solution allows the building to function in a way similar as originally intended, a decision that has educational value for the building sector," said Ángel Borrego Cubero, the architect of La Carboneria's rehabilitation.

It was impossible to restore the existing street art mural due to the deterioration of the base stucco under the windows, which was peeling off. In addition to this and, according to city heritage regulations, the façade had to recover its original, historical condition.

Also, its reuse as the public façade of a rehabilitated estate seemed very doubtful, as it would be something contrary to the original intention of the authors of the mural. Efforts were made to keep Mr. Garriga's traditional furniture shop, which was finally achieved.

Site plan

Ground floor plan

First floor plan

Second floor plan

Axonometric floor plan

Project facts

Architect: Office for Strategic Spaces (Ángel Borrego Cubero)

Local architect: Montserrat Farrés Catalá (mmj arquitectes)

Consultants: Xavier Aumedes / ARREVOLT (Quantity Surveyor); BAC ENGINEERING (Structure, HVAC, Electricity); Aleksandar Ivancic /AIGUASOL ENGINYERIA (Energy Efficiency); Cristina Thió / CHROMA (Chromatic historical study of the façade)

Developer: Lesing LWP Spain S.L.

Completion year: 2022

Location: Barcelona, Spain

Built area: 1200 m2 or 13,000 sq.ft.

Floors: 5

All images © Simona Rota.

All drawings © Office for Strategic Spaces.